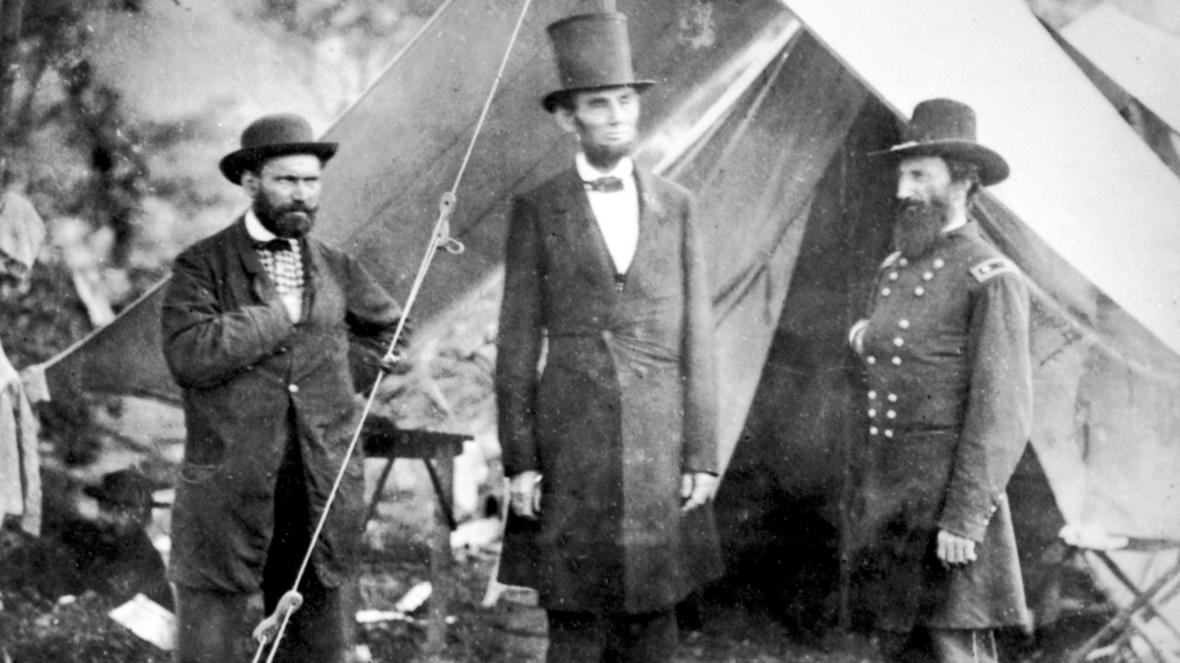

Allan Pinkerton, far left, foiled a plot to kill Lincoln.

Lewis tried to play it cool, insisting he was a friend of Webster calling in to see how he was doing. After the senator’s son gave a positive ID on the two Pinkertons – whose names were already known to the Confederates – Lewis tried to escape on the night of 16 March, having filed the bars on the prison windows. Unfortunately Lewis was picked up 20 miles (32km) from Richmond on the Fredericksburg road. He was returned to jail and clapped in irons.

On 1 April, Scully and Lewis were found guilty of spying and sentenced to be hanged four days later. Lewis had one last card to play. The Confederacy was trying to gain recognition from Britain and he and Scully were still subjects of Queen Victoria. Lewis gave the prison chaplain a letter for the British consul, asking for the Crown’s protection. Although the consul arrived and promised to help, Scully was near breaking point. Dissolving into tears, Scully admitted he had written to Winder and, if pardoned, would reveal everything he knew. This course of action was confirmed when the guards removed Lewis from the cell so that Scully would not be influenced by him.

Not long after, Lewis saw a carriage arrive at the prison and was horrified to see Webster and Lawton being led out as captives. Scully had betrayed them. Expecting to be executed at 11.00am on the morning of 4 April, Lewis was told that President Davis had delayed the execution for two weeks. This was to allow for a trial, with both Scully and Lewis called as witnesses against Webster. The Confederates were furious they had allowed themselves to be duped by Webster and wanted swift revenge. While Scully spilled the beans, Lewis tried his best to protect Webster. The trial was a foregone conclusion. The increasingly frail Webster was sentenced to death with all haste, lest Webster died of his illness first. Lawton was sentenced to a year’s imprisonment as his accomplice, while Scully and Pryce Lewis were spared the gallows as British subjects.

When Pinkerton learned of the trial from a Southern newspaper he was beside himself with anguish. The matter went as far as Lincoln, who wrote to President Davies pointing out that Confederate spies had not been executed in the North. With this came the obvious threat – if Webster was executed, Southern spies could expect the same treatment. The pleas went unheard and Webster was given a public execution. With no proper executioner, it took two attempts to hang him. On the first attempt the noose was too loose and ended up round Webster’s waist and on the second attempt, it was so tight it almost throttled him before the trapdoor was released.

The loss of Webster seemed to mark the beginning of the end for Pinkerton as secret service chief. As a general, McClellan was heavily criticized for being over cautious. One of the main reasons given for this caution was Pinkerton’s mistakes in reporting the Confederate order of battle, which he constantly over-exaggerated. In March 1862, McClellan advanced with 85,000 troops against Richmond. Encountering resistance at Yorktown, McClellan quickly halted and settled down for a month-long siege. Against him were no more than 17,000 troops, but Pinkerton’s intelligence was faulty. During the course of the siege the Confederates received reinforcements, bringing their strength up to 60,000 men. At the same time McClellan’s forces grew to 112,000 strong, but he still believed the Confederates to have twice as many troops as was the case. When McClellan finally broke through and resumed his advance on Richmond, the Confederate army was reinforced by General ‘Stonewall’ Jackson. Its actual strength was in the region of 80,000 men: Pinkerton reported it to be 200,000 and McClellan decided to retreat.

On 5 November, Lincoln replaced McClellan and in so doing ended Pinkerton’s active involvement with the war. The detective’s fault was not in an inability to gather intelligence, but in his appreciation of it. As Landrieux had written of his time in Italy, the head of a military secret service had to be a soldier because a civilian policeman would ‘understand almost nothing’. Pinkerton was living proof of this. He had been successful at counter-espionage, which was above all, police work, but it was commonly agreed that Pinkerton was an abject failure with military intelligence. This failure also proved in the long run, very bad for business. Washington disclaimed any responsibility for Pinkerton’s expenses, arguing that he was the private employee of General McClellan. He was replaced by a Secret Service Bureau under Lafayette Baker (1826–68) who was appointed by Secretary for War Stanton.

Previous to this assignment, like Webster, Lafayette Baker had been working as a spy behind enemy lines. His modus operandi was to pose as an itinerant photographer, which he did with aplomb, despite his camera being broken and without film. On his travels he met Jefferson Davies and interviewed General Beauregard. Finally he was rumbled at Fredericksburg when one inquisitive spark wondered why he was the only photographer never to have any photographs with him. The jig was up and Baker escaped back to Union lines.

Perhaps the most significant example of military espionage in the war came during the build-up to the battle of Gettysburg (1–3 July 1863), the largest battle ever fought on American soil. In brief, the Confederate general Robert E. Lee had invaded the Union with the 75,000-strong Army of Northern Virginia. While advancing along the Shenandoah Valley towards Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, Lee was reliant on a cavalry screen to protect his march. Under the command of General J. E. B. Stuart, the Confederate cavalry went raiding instead, leaving Lee and the entire army blind. While Lee waited vainly for news from Stuart, the commander of I Corps, General James Longstreet, sent a spy to accomplish what Stuart had not.

This spy was identified by Longstreet in his memoirs as a scout named only as ‘Harrisson’. It was not until the 1980s that he was finally identified as Henry Thomas Harrison (1832–1923), a native of Nashville, Tennessee. In 1861, Harrison joined the Mississippi State Militia as a private and was often employed as a scout. In February 1863 he came to the notice of the CSA Secretary of War, James Seddon, who brought him to Richmond and employed him as a spy. In March Seddon sent Harrison and several others dressed as civilians to General Longstreet, recommending he use them as scouts. To test them, Longstreet sent them on missions, including finding a passage through the swamps in the direction of Norfolk. Of those sent, Harrison was marked out as ‘an active, intelligent and enterprising scout’ and was retained in Longstreet’s service.

It is worth noting here that although Longstreet politely refers to Harrison as a ‘scout’ he was dressed as a civilian, thus making him in the eyes of the law a spy. As is so common in the story of espionage, spies were distrusted and thought to be double traitors, giving away as much information to the enemy as they received back from them. Even Longstreet was cautious when dealing with Harrison lest he was betrayed. When he sent Harrison to go to Washington and to glean as much intelligence as possible he would not answer Harrison’s query about where he should report to after the mission was accomplished. In one version of the conversation, Longstreet told Harrison the headquarters of I Corps were large enough for any intelligent man to find. Another version, given by Longstreet’s chief of staff, Gilbert Moxley Sorrel, has the general saying: ‘With the Army; I shall be sure to be with it.’ Wryly, Sorrel noted such a precaution was unnecessary as Harrison ‘knew pretty much everything that was going on’.

According to Sorrel, Harrison’s instructions were to proceed into the enemy’s lines and to remain there until the end of June, bringing back as much information as he could. He returned on the night of 28 June, finding Longstreet’s headquarters at Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. ‘Travel-worn and dirty’, he had been arrested while trying to cross back through the Confederate picket lines and was taken to Longstreet’s camp by the provost guard. Sorrel recognized him and debriefed him immediately. Harrison’s report was long and, as events would prove, completely accurate. He explained how the Union Army of the Potomac had quit Virginia and started in pursuit of Lee in great numbers. Two Federal corps had been identified around 50 miles (80km) away at Frederick and George Meade had recently been placed in command of the army, in place of General Hooker. Recognizing the importance of the report, Sorrel took Harrison to Longstreet and woke him up. Hearing the news, Longstreet lost no time in sending Harrison directly to General Lee’s camp with one of his staff officers, Major John W. Fairfax.

Arriving at Lee’s tent, Fairfax entered and announced that one of Longstreet’s scouts had arrived with information that the Union army had crossed the Potomac and was marching north. Lee had spent the day fretting over Stuart’s lack of communication and Fairfax’s report appears to have startled him. ‘What do you think of Harrison?’ asked Lee. ‘General Lee,’ replied Fairfax, ‘I do not think much of any scout, but General Longstreet thinks a good deal of Harrison.’ ‘I do not know what to do,’ came Lee’s blunt reply after a moment’s reflection. ‘I cannot hear from General Stuart, the eye of the Army. You can take Harrison back.’

Later that night, after absorbing the shock that he was in severe danger from an unknown force, Lee sent for Harrison. In what must have been a lengthy interview, Lee patiently listened to Harrison’s entire report: how he had left Longstreet at Culpeper and had gone to the Union capital, Washington, where he had picked up gossip in saloons. Hearing the Union army had crossed the Potomac in pursuit of Lee, Harrison recalled how he set out for Frederick, mixing with soldiers during the day and moving on foot by night. At Frederick he had identified two infantry corps and had heard of a third nearby, which he had been unable to locate. Learning that Lee’s army was at Chambersburg, he found a horse and hurried back to reveal the position of the Union army. On the way there, he learned that at least another two corps were in the vicinity and that General Meade had taken control of the army.

With no other option but to believe Harrison, Lee gave the orders to concentrate in the direction of Gettysburg. Many applaud Harrison for saving the Confederate army from being attacked in the rear, but ironically, in so doing, he also led it to disaster. Against Longstreet’s advice, after unexpectedly encountering lead elements of the Federal army at Gettysburg, Lee attacked Meade for three days of confused and bitter fighting. The battle was a heavy defeat for the Confederacy, losing men and commanders it could ill afford to replace. At the end of it Lee was forced to retreat back across the Potomac.

Later in the year Harrison obtained permission to return to Richmond. Before leaving headquarters he told Sorrel he was appearing on stage in the role of Cassio, in Shakespeare’s Othello. When Sorrel asked Harrison if he was an actor, the spy explained he was not, but he was doing the performance to win a $50 wager. Sorrel saw the performance – Cassio was unmistakably Harrison – and noted that the entire cast seemed quite drunk. Although perhaps just harmless fun, Sorrel decided to investigate Harrison’s indulgencies more closely. When he found Harrison had a reputation for heavy drinking and gambling, Sorrel concluded he was not safe to be employed as a spy. Harrison was dismissed from Longstreet’s service in September and sent back to the Secretary of War.

The American Civil War was notable for the number of female agents on both sides. Already we have seen Rose Greenhow, Kate Warne and Carrie Lawton. To these must be added ‘la belle rebelle’ Belle Boyd (1844–1900) who at 17 shot an overly exuberant Federal soldier on her doorstep when he tried to raise the Union flag over her Virginia home. During the Shenadoah Valley campaign of 1862, Boyd famously ran across a battlefield to deliver vital intelligence to ‘Stonewall’ Jackson. He was so impressed with her exploits, he made Boyd captain and honorary aide-de-camp on his staff. Boyd later travelled to Britain where her autobiography became a bestseller.

Sarah Emma Edmonds (1842–98) enlisted in the Union army under the name Frank Thompson. Volunteering for a mission behind enemy lines at Yorktown, Edmonds gained entrance to Confederate camps near Yorktown, Virginia, disguised as an African-American slave, having bought a wig of ‘negro wool’ and stained her skin with silver nitrate.

She was assigned to work on construction of the Confederate ramparts opposite McClellan’s position and noted how logs were being painted black to look like guns. Unfortunately, the heavy work took its toll on Edmonds’ disguise. As she began to sweat, the silver nitrate began to fade. Popular legend has it that a slave noticed Edmonds’ skin was becoming paler and pointed this out. Edmonds coolly replied that she always expected to become white one day, as her mother was a white woman. This excuse was apparently accepted. On the second day of her mission, Edmonds was sent out to the Confederate picket line to replace a dead soldier. From there she made her escape to Union lines.

Pauline Cushman (1833–93) also merits an honourable mention. An actress from New Orleans, Cushman followed the Confederate army ‘looking for her brother’, but in reality spying for the North. She was captured and sentenced to be hanged, but was rescued by Union troops in the nick of time. President Lincoln made her an honorary major. Also of great service was the freed slave Mary Touvestre, who was housekeeper to a Confederate engineer in Norfolk, Virginia. She stole a set of plans for the first Confederate ironclad warship and took them safely to Washington.

But of all the female agents – Greenhow included – the connoisseur’s choice must be ‘Crazy Bet’ Elizabeth Van Lew (1818–1900). From a Northern family settled in Richmond, Van Lew did not hold with the Southern way of living. When her father died, she used her inheritance to free the family slaves, an act which gained her a reputation among polite, Southern society as something of an eccentric.

After the arrival in Richmond of Union soldiers taken prisoner at Bull Run, Van Lew obtained a pass from General Winder to visit them. While providing them with food, medicine and clothing, Van Lew began collecting messages from the prisoners, which she had smuggled to their homes. This simple act of generosity soon developed into an espionage network, known as the Richmond Underground. This comprised of an elaborate network of spies, messengers and escape routes for prisoners she helped break out of prison. By way of an example, in 1864 Van Lew was responsible for the escape of 109 prisoners, half of whom she quartered at home while waiting to be smuggled back north. Of course, Winder was not entirely unaware of Van Lew’s activities. From 1862 he had her under surveillance, but without success. Aware she was being watched, Van Lew began to act very strangely, confirming suspicions she was unbalanced, if not actually insane.

Van Lew’s spy ring was centred on one of her former family slaves, Mary Elizabeth Bowser. Early in the war, Van Lew obtained Bowser employment as a servant in the home of the Confederate president. As an African-American female servant, she was ignored by the president’s guests who did not suspect Bowser was carefully eavesdropping on their conversations, or reading documents on Jefferson’s desk while going about her chores. To collect reports from Bowser, Van Lew recruited a local baker who made deliveries to the Confederate ‘White House’. The baker collected the messages for Van Lew, who enciphered them and passed them to an old man – another former slave – who took them to the Union’s General Grant, hidden in his shoes. Again, because the man was seen as a slave, he passed unnoticed under the auspices of carrying flowers.

In 1864 Winder made another attempt to catch Van Lew red-handed. He ordered her property searched by troops, who found nothing, despite there being prisoners hidden in a secret room on the third floor. After the raid, Van Lew went into an apoplectic spasm in Winder’s office, declaring him not a gentleman and forcing an apology from him. A few short months later the war was over and General Grant made a special point of visiting Van Lew, thanking her for the excellent intelligence he had received from Richmond. Unsurprisingly, Van Lew’s neighbours were less than pleased to learn the full extent of her treachery. ‘Crazy Bet’ spent the next 35 years of her life despised as an outcast and a traitor.