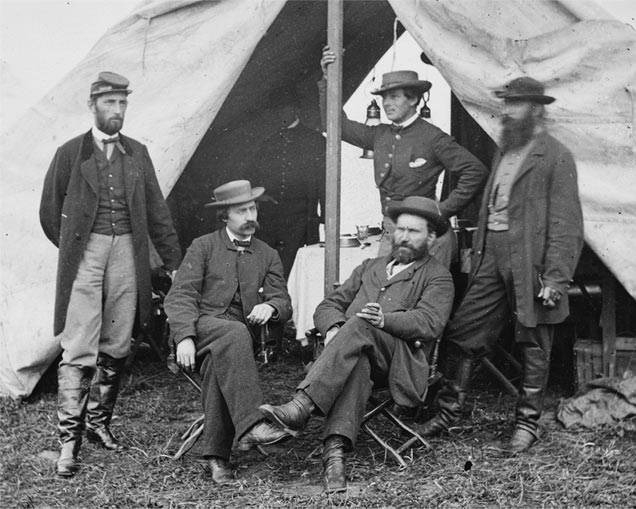

Seated: R. William Moore and Allan Pinkerton. Standing: George H. Bangs, John C. Babcock, and Augustus K. Littlefield

The problem with journalists ‘spying’ on armies continued in the American Civil War (1860–65). Up to 150 war correspondents followed the Union Army, along with photographers and artists, serving the big Northern dailies. War was being reported faster than at any time in history and in much more detail. Troop movements, plans and orders of battle were served up to a news-hungry public back home. They also became one of the Confederate Army’s main sources of information. The Washington and Baltimore newspapers were arriving on the desk of Confederate President Jefferson Davis within 24 hours of being printed, while those of New York and Philadelphia arrived a day later.

Attempts were made to limit the damage, with sometimes farcical results. On 2 August 1861, General McClellan made Washington correspondents agree not to report sensitive information without the permission of the commanding general. Two months later, Secretary of War Simon Cameron happily gave the New York Tribune a complete order of battle run-down of the Union forces in Missouri and Kentucky. In 1862 an attempt by the War Department to introduce telegraph censorship met with hostility and the Lincoln administration was accused of using security as an excuse to stifle public debate on the running of the war.

The problem appears to have become less acute after it was required for journalists to submit their reports to provost marshals before filing them. General William T. Sherman, a man with little time for reporters, went a step further and insisted that correspondents were ‘acceptable’ to him before they were allowed to work at the front. By 1864, the press co-operated better and Sherman’s famous ‘march to the sea’ was done without being reported. The problem seems to have been very much one-sided. While Union commanders were frustrated by the presence of journalists at the front, the Confederates excluded them from the frontline altogether. The need for strict censorship appears to have been better understood by those few Southern newspapers continuing to run during the war.

One of the most colourful secret service figures in the American Civil War was Allan Pinkerton (1819–94), the Scottish-born founder of the detective agency bearing his name. Famous for railroad protection and running down such notorious desperados as the James Gang, the Wild Bunch and Butch Cassidy, the company logo was an all-seeing eye with the motto ‘we never sleep’ – hence the expression ‘private eye’.

In January 1861, Samuel Felton, president of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad, hired the Pinkerton agency to protect his company from sabotage by secessionist sympathizers in the Baltimore area. Pinkerton agreed the contract and took six of his operatives to infiltrate the secessionists. Alongside Pinkerton was detective Timothy Webster, an English-born New York City policeman and without doubt the agency’s top undercover man. Webster passed himself off as sympathetic to the South and enrolled in a rebel cavalry troop formed to resist ‘Yankee aggression’. Another agent, Harry Davies, was already familiar with many of the leading secessionists, having previously lived in the South. It was Davies who first discovered a plot to assassinate President-elect Abraham Lincoln (1809–85).

The sixteenth president of the Union, Lincoln had been elected on 6 November 1860. Although billed as ‘Honest Abe’, many saw his winning the presidency as akin to the coming of the Antichrist. In Baltimore an excitable Italian barber at Barnum’s Hotel named Cypriano Fernandina formed a conspiracy to assassinate Lincoln. The Italian’s motives are unclear, except to say that many of his best customers were secessionists. According to Davies, Fernandina had called a secret ballot from which eight assassins had been chosen. Before his March inauguration, the Republican president-elect had to travel to Washington by train, working to a publicized timetable. When he stopped at Baltimore, a fracas would break out to divert police attention away from Lincoln and the assassins would strike. Learning of this plot Pinkerton went straight to Philadelphia to consult with Felton.

Meanwhile, Lincoln had left his home in Springfield, Illinois, on 11 February. He arrived at Philadelphia on 21 February and was introduced to Pinkerton, who outlined the plot. It took some effort to convince Lincoln that someone was willing to assassinate him, but eventually he came round to the idea and agreed that Pinkerton should make arrangements for his safe transport to Washington. Deviating from the schedule, Lincoln left a dinner in Harrisburg early and boarded a special train provided by Felton. To prevent secessionist spies transmitting details of his unscheduled departure, Pinkerton had the telegraph lines cut. At Philadelphia, Lincoln joined the night train to Washington. Along the route between Philadelphia and Washington, Pinkerton and Felton placed reliable men posing as members of a work gang whitewashing railroad bridges apparently in an attempt to make them fireproof. These men were given lanterns in order to signal that the train had safe passage through their sector.

Throughout the journey, Lincoln posed as an invalid travelling with his sister, a role played by Kate Warne. A Pinkerton agent since 1856, Warne is celebrated as America’s first female private detective. Pinkerton claimed Warne approached him wanting to be a detective, but others think Warne was looking for a job as a secretary. Although there were no vacancies, Pinkerton employed her anyway because he took a shine to her. She then became Pinkerton’s mistress and would pose as his wife on certain missions.

The president-elect made it to Washington unharmed and when the plotters realized they had missed their chance, they melted away. Many believed the whole Baltimore conspiracy was a stunt engineered by Pinkerton himself. Pinkerton was a good businessman. If he was paid to uncover conspiracies, then conspiracies he found. If the conspiracies were magnified to ensure the customer felt that he or she was getting value for money, well … business is business, as they say.

After the first shots of the war were fired, Pinkerton again offered Lincoln his services. The detective was invited to Washington and asked for his advice in dealing with Southern sympathizers, but was not given the contract he was seeking. Instead Pinkerton was asked to form a secret service for the army of General McClellan who commanded the Military Department of the Ohio. Setting up shop in Cincinnati and using the alias of E. J. Allen, Pinkerton launched his agents into the Confederacy on McClellan’s behalf.

Posing as a Georgia gentleman, Webster was the first agent to move south, heading in the direction of Memphis. Even Pinkerton got in on the act and crossed the Ohio. He had a lucky escape when a German barber from Chicago recognized him, but did not denounce him. Another of Pinkerton’s Englishmen, Pryce Lewis, set off in June 1861, travelling through the Confederacy as a neutral tourist. Near Charleston he was stopped and interrogated by a Colonel Patton. Grandfather to General George S. Patton, the Confederate colonel was so sure of Lewis’ credentials that he took him on a tour of the fortifications he commanded.

On 22 July 1861 McClellan was given command of the Army of the Potomac and charged with protecting Washington. He immediately invited Pinkerton to follow with his secret service. The most pressing need at that time was for a counter-espionage service, as both Baltimore and Washington were alive with rebel spies and supporters. While Pinkerton dispatched Webster and the agent Carrie Lawton to Baltimore to infiltrate rebel cells, he concentrated on snaring the top rebel spy in Washington. This agent was supposed by many, including Assistant Secretary of War Thomas Scott, to be the politically well-connected socialite widow Rose O’Neal Greenhow (1817–64).

Greenhow had been recruited as a spy at the beginning of the war by West Point graduate Thomas Jordan, a US officer who joined Confederate General Beauregard’s staff. Before leaving Washington, Jordan provided Greenhow with a simple cipher and instructions to contact him using his alias – Thomas J. Rayford. In July 1861 she scored a significant coup when she sent a copy of Union General McDowell’s orders for the Army of the Potomac, which was to advance into Virginia. Forewarned, General Beauregard caused the Union army an embarrassing defeat at Bull Run on 21 July.

Pinkerton put Greenhow and her contacts under close surveillance. By all accounts Greenhow unsuccessfully tried to pull strings with government friends to have Pinkerton called off. Then, one rainy August evening, Pinkerton and three agents, including Pryce Lewis, tailed an officer to Greenhow’s home. When an upstairs light came on, Pinkerton had his men form a human pyramid with himself at the apex. Glimpsing into the room, Pinkerton saw the young officer handing Greenhow a map and heard him give instructions on how to read it. Then the two went into a back room, where Greenhow no doubt favoured the traitor with a reward. An hour later, the officer departed Greenhow’s home with a kiss. Pinkerton had the officer arrested and, when confronted with the evidence, he later committed suicide in his cell. Meanwhile an embarrassing list of prominent figures were seen coming and going from the Greenhow home, including former president James Buchanan.

Having heard enough, Scott ordered Greenhow’s arrest. On the day of the arrest, Greenhow was found in her parlour reading a book. While Pryce Lewis stood guard over her, Pinkerton searched the house and recovered an amazing hoard of classified Union documents including plans of Washington’s defences and fortifications. Prize among them was Greenhow’s diary, which detailed the full extent of the Confederate spy ring. In terms of counter-espionage, the find was priceless. It gave the names of Greenhow’s contacts, her informants and means of delivering messages to the Confederacy – numerous arrests followed. At one point in the search, Greenhow pulled a pistol on Lewis, but failed to cock it properly. Otherwise the only real trouble came from her eight-year-old daughter, who hid up a tree outside the property and called down a warning to anyone she recognized approaching the house: ‘Mother has been arrested!’

With Greenhow in custody the problem arose of what to do with her? She was too well connected and too much a celebrity to send to the gallows, but the number of prominent soldiers, politicians, bankers and so on involved with this conspiracy made her presence acutely embarrassing for President Lincoln. This problem was exacerbated when Greenhow continued sending messages to Richmond from jail, including an unflattering account of how Pinkerton had arrested her. In the end, after a trial, Greenhow was sent to Richmond where she continued her celebrity lifestyle. She was later sent on a mission to London, where she had an audience with Queen Victoria and to Paris where she was received at the court of Napoleon III. After writing her memoirs she returned to the Confederacy in 1864 on the blockade-runner Condor. Chased by a Union gunboat, Condor ran aground and Greenhow drowned.

While Pinkerton had been busy with Greenhow, Timothy Webster had been making a name for himself among Confederates and their Maryland acolytes. Working so far undercover, Webster was actually arrested by a Federal detective who believed he was a Confederate spy. Webster could not hope for better credentials to maintain his cover. While under arrest, he met with Pinkerton who arranged for him to ‘escape’ while being transferred to Fort McHenry for internment. Hand-picked guards even fired shots after the escaping Webster, all to give the agent more credibility. Arriving at a safe house in Baltimore, Webster had become a hero of the cause. Even when a man denounced him after seeing Webster with Pinkerton, the Union agent simply punched the man in the jaw and called him a damned liar.

From Baltimore to Richmond, it seemed Webster had the run of the Confederacy. His intelligence reports from behind enemy lines were exhaustive and accurate. Set up in a top Richmond hotel, Webster was so believable that the Confederate Secretary of War entrusted his personal letters to him for delivery to Baltimore. This of course allowed Pinkerton to read the letters, which lead to a number of high-profile arrests.

In support of Webster, other Pinkerton agents were sent south, including John Scobell, a former Mississippi slave recruited to the agency in the autumn of 1861. Scobell performed a variety of roles, sometimes posing as a cook or labourer, other times acting as a servant to Webster or Carrie Lawton. Another of his means of gaining intelligence was through his membership of the Legal League. This was a secret African-American organization in the South, the members of which often helped Scobell by providing couriers to carry his information across Union lines.

However, as the war entered its second year and McClellan was planning another offensive, Webster began to suffer from illnesses brought about by his constant exposure to the elements. After feeling the effects of rheumatism while accompanying Carrie Lawton on a mission to Richmond, Webster fell seriously ill and stopped reporting. Desperate for news on the eve of the new offensive, Pinkerton made the cardinal error for spymasters. He became impatient.

When Pinkerton asked Pryce Lewis to replace Webster, the Englishman baulked at the idea and refused the assignment. Then, when Pinkerton convinced him otherwise, he told Lewis that another agent, John Scully would be joining him. Their cover would be as smugglers carrying a letter to Webster from Baltimore. It was an ill-conceived plan.

On the afternoon of 27 February 1862, the two Union spies were at Webster’s sick bed when the Confederate detective Captain Sam McCubbin entered the room only to check on Webster’s progress. The feeling of relief was only temporary, for McCubbin was followed by the son of a former senator, whom Lewis and Scully had guarded after Pinkerton had ordered their family arrested. Before they had a chance to escape, Lewis and Scully were seized and taken before General Winder, head of Confederate secret police, who suspected they were both spies.