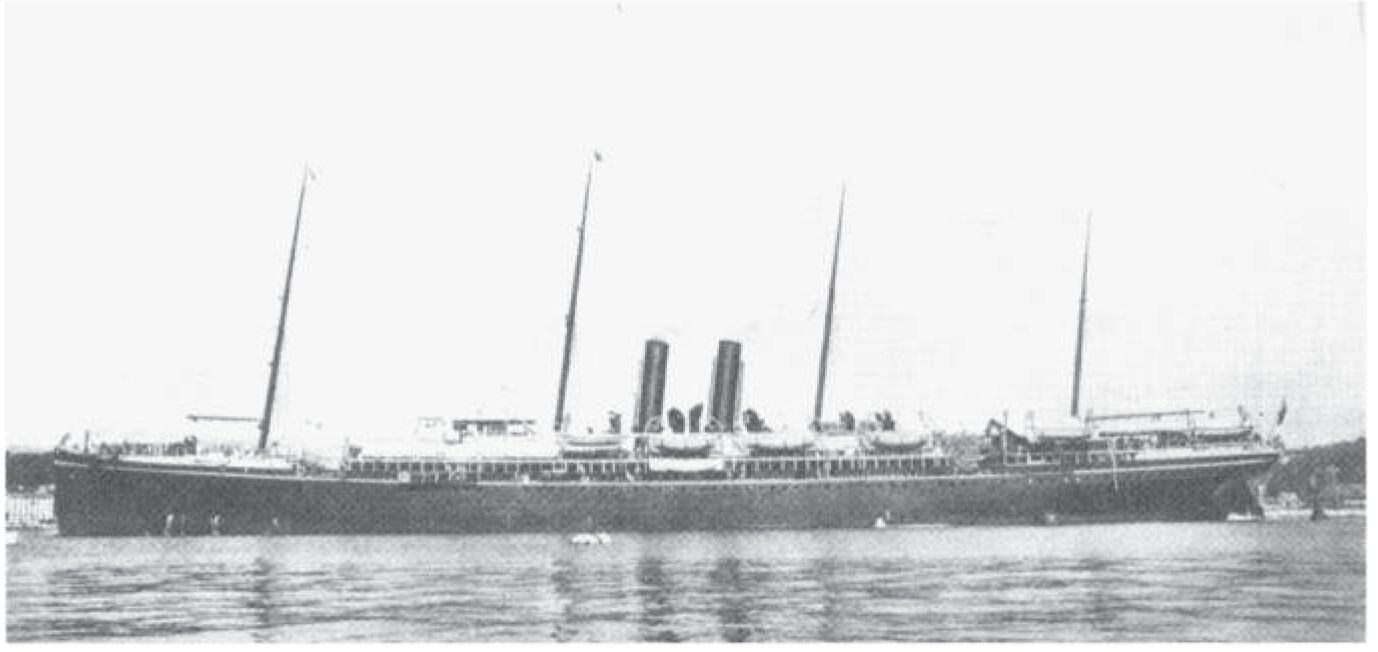

The P & O liner Iberia was requisitioned to carry troops to the Sudan

The first Australian troops to go overseas left Sydney in March 1885, when, following the murder of General Charles Gordon in Khartoum, the colony of New South Wales raised a small contingent to assist British forces fighting an outbreak of hostilities in Sudan. This first deployment of Australian troops overseas was rapidly arranged, in response to the public outcry over the death of Gordon, who was the most famous British general of his time. Although Gordon was killed on 26 January 1885, news of his death did not reach Australia until 11 February. Two days later, William Dalley, Acting Premier of New South Wales, sent a message to the British government offering the service of a contingent of soldiers from the colony to assist British soldiers already fighting in Sudan. It was decided the New South Wales force would comprise an infantry battalion of 522 men, with 24 horses for officers, and two artillery batteries numbering 212 men and 172 horses, to be dispatched as soon as possible.

Once the decision to raise this force had been taken, there were some doubts that it could be achieved, given the short time available to select and equip the contingent, but so many men volunteered the major difficulty was in choosing the right men for the job. Those selected were immediately sent to Victoria Barracks, in the Sydney suburb of Paddington, for training.

Meanwhile, two passenger vessels then berthed in Sydney, Iberia and Australasian, were requisitioned to transport the contingent to the Sudan. Iberia was the larger and older, having been built in 1874 for the Pacific Steam Navigation Company. Initially used on their service from Britain to South America, Iberia joined the Australian trade in 1883, and had already been used to transport British troops to Egypt for the Sudanese war. The single-funnelled Australasian, owned by the Aberdeen Line, was quite new, having entered service in 1884, and was one of the first steamships in the world fitted with triple expansion machinery, but as with Iberia, having a hull built from iron. The black hulls of both ships were quickly repainted white for their trooping duty, and they looked very smart. Also, as befitted their temporary status as troop transports, they were given official numbers, with Iberia having 1 NSW painted on its sides, while Australasian was 2 NSW.

On Saturday, 28 February, with 50,000 people watching, the entire contingent paraded in an official review in Moore Park, while the following day, special church services were held in honour of the troops, and 2 March saw many of the men making their final farewells.

Tuesday, 3 March 1885, was to become one of the most important days in the history of New South Wales, for, as the Sydney Mail stated that day, ‘our men have the proud pre-eminence — in the matter of which every good and true man in the other colonies will envy them — of being the first selected to strike a blow for the old country in her hour of need in Africa.’ In the morning, the troops gathered in the grounds of Victoria Barracks, where they had a final chance to enjoy the company of family and friends. At midday, a bugle sounded for the troops to fall in, and they prepared to march to Circular Quay, where the Australasian and Iberia awaited them. A newspaper recorded how, following the bugle call, there were ‘hurried squeezes of the hand, a last kiss to sweethearts, wives or sisters, and the men seizing their rifles rush off amidst numerous goodbyes to their position. There occurs a brief interval during which the roll of each company is called. The men amidst loud cheering, waving of handkerchiefs, and the tap of the drum, the movement from New South Wales to Egypt had commenced. The band played one of the liveliest marches and the men trooped out, their bearing, their physique, and the smartness of their dress, at once challenged and won general admiration.’

Along the route from Victoria Barracks to Circular Quay the marching men passed down streets thronged with an estimated 200,000 cheering spectators, about two-thirds of the population of Sydney. On reaching the wharf, all the infantrymen and some members of the artillery boarded the Iberia, on which the officers were allocated berths in cabins while the other ranks had to make do with hammocks strung up in the ’tween decks. The majority of the artillerymen went on board the Australasian, where the officers were again allowed to use cabins while the other ranks were allocated the accommodation used by emigrants on the voyage from Britain to Australia. Also going on board the Australasian were the 218 horses, which were put into specially constructed stalls in the holds.

As the ships prepared for departure, the troops were addressed by Lord Loftus, the Governor of New South Wales, who told them: ‘Soldiers of New South Wales, for the first time in the great history of the British Empire, a distant colony is sending, at her own cost, a completely equipped contingent of troops who have volunteered with enthusiasm of which only we who have witnessed it can judge.’ As departure time neared, an armada of vessels of all shapes and sizes began to throng the harbour. Despite the seriousness of the occasion, the day assumed more of a festive air, though before it was over there would also be tragedy.

Iberia was the first of the troopships to leave the wharf, shortly after 3 pm, followed minutes later by Australasian. As the pair proceeded slowly down harbour, they were surrounded by steamers carrying wellwishers, while every vantage point ashore was packed. As the two ships rounded Bradleys Head, Australasian moved ahead of Iberia, while bands aboard surrounding boats played merrily such patriotic tunes as ‘Rule Britannia.’

One of the larger vessels escorting the troopships that day was the coastal steamer Nemesis, owned by Huddart Parker Limited, which was carrying a large number of relatives and friends of departing soldiers. Among them was Elizabeth Sessle, waving farewell to her husband, Private F. Sessle, who was on board Iberia. Elizabeth was carrying their fifteen-month-old child, and with them on the Nemesis was a friend and neighbour, Ann Capel. Elizabeth located her husband standing at the railings of Iberia, and to get a better view moved forward on the starboard side towards the bow of Nemesis, then held her child up for her husband to see.

By now, Australasian had passed through Sydney Heads and was heading off down the coast, while Iberia was off South Head, still moving very slowly. Suddenly Iberia began to surge ahead as power was increased, and in doing so the order was given to turn to starboard. In performing this manoeuvre, the port quarter of Iberia smashed into the starboard bow of Nemesis, with a crash that could be heard by those on shore. The impact caused minor damage to one of the lifeboats on Iberia, but the forward section of Nemesis was devastated by the accommodation ladder still hanging down the side of the troopship. In an instant, Ann Capel was killed, while Elizabeth Sessle was severely injured, and the infant she was holding suffered a fractured thigh.

Despite the collision, Iberia continued on course and was soon out at sea, joining up with Australasian. The two ships were accompanied by some of the vessels that had escorted them down the harbour, until off Bondi the last escort vessel turned around, and the pair of troopships disappeared to the south at the start of their long journey, raising sail on their masts to increase their speed. On board Iberia, Private Sessle, who had seen the collision, could only wonder what had happened to his wife and child. Immediately after the collision, Nemesis steamed at top speed back to her berth. Elizabeth Sessle was rushed to hospital, but so severely had she been injured, she died the same night.

Such was the nationalistic fervour generated by the departure of the first Australian troops overseas, the next day the Sydney Mail trumpeted: ‘Tuesday the 3rd March 1885, will be forever a red-letter day on which this colony, not yet a hundred years old, put forth its claims to be recognised as an integral portion of the British Empire … This day marks an entirely new departure as regards the relations between the Old Country and her colonies. Hitherto the colonies have been regarded by many politicians as a drag upon the home country, and statesmen have been heard to say that the colonies of England were a source of weakness to her, not strength. The fallacy of such statements was demonstrated beyond dispute by the events of yesterday. If ever there was in the history of the world an occasion where everything that had been arranged was performed to the letter, if ever there was a day when a programme literally arranged was carried out satisfactorily it was yesterday, when the chosen troops of New South Wales, the picked men of the colony, embarked for the purpose of assisting the British arms in the Sudan.’

As the troopships headed south from Sydney they ran into bad weather and heavy seas, which resulted in many men succumbing to seasickness. One trooper wrote in his diary how ‘the ’tween deck was so crowded and the stench was horrible.’ After passing through Bass Strait, the two ships headed west, but Iberia took a more northerly course and on the evening of 6 March stopped for two hours off Kangaroo Island, where it was soon surrounded by numerous pleasure craft packed with residents of Adelaide. During the brief stop, troopers were able to send off final letters to loved ones, and Private Sessle left the ship to return to Sydney. A large quantity of fruit was taken on board, while two men and a young boy who came on board Iberia tried to stay as stowaways, but were found and sent off in a boat before the Iberia continued its voyage. The last sight of Australia for the troops on board was on 10 March, as Iberia passed Cape Leeuwin.

More bad weather was encountered as the two ships crossed the Great Australian Bight. This caused the captain of the Australasian to order a reduction in speed, primarily to avoid an injury to the horses in their stalls. Instead of slowing to stay with her companion, Iberia steamed on ahead at her normal speed.

On board, a daily routine was quickly established. Breakfast was at 8 am, lunch at 1 pm and supper at 5 pm, and on the whole the food supplied was good and in adequate quantity. During the day, fruit was issued at 11 am, and at 1.30 pm there was an issue of beer and lime juice. In between meals, the troops went through exercises and training routines, except on Saturday, when sports contests were held, and Sunday, when religious services were held, led by the Anglican and Roman Catholic chaplains on board.

As the ships steamed across the Indian Ocean towards the Sudan, back in Sydney parliament convened on 17 March to actually give their approval to the dispatch of the troops. So swiftly had the contingent been organised and sent away that parliament had not had an opportunity to meet and debate the matter, but there were only a few dissenting voices when the members did get down to discussions. One notable voice of dissent was Sir Henry Parkes, who was a persistent critic of Dalley and the contingent. As Dalley said, ‘We have undoubtedly strained the law … It is for parliament to determine whether we are to be censured or supported.’ In the end the motion to support the dispatch of the contingent was passed without a division on the evening of 19 March.

By then, Australasian and Iberia were well into the Indian Ocean, following a north-westerly course that soon took them into the tropics, Iberia crossing the equator on 22 March. Of course, the ships were totally out of touch with events happening in the Sudan, so as the voyage progressed some of the officers from the contingent pressed the ship’s captain to increase speed, as they were fearful the conflict might be over before they arrived. Their first port of call was to be Aden, at the southern end of the Red Sea. As Iberia neared Aden, she passed another Orient Line vessel, Lusitania, bound for Australia, and the troops lined the rails to wave to the passing ship, whose passengers waved back.The next day, 26 March, Iberia dropped anchor off Aden, and those on board finally received news of what was happening in the Sudan. Orders were received that the contingent was to proceed to Suakin, and the troops would be sent to the front right away. This news filled all on board with pride and excitement. Prior to leaving Aden, two men were sent ashore, one with a broken ankle, the other with spinal damage, to be returned to Australia on the first available ship. As Iberia steamed up the Red Sea, live ammunition was distributed to all troops, who busily cleaned their rifles and other weapons.

Iberia dropped anchor off Suakin at noon on Sunday, 29 March, and the Australian troops marched ashore to begin an association with Africa that would encompass four wars. Australasian arrived the next day and immediately disembarked her troops and horses. Despite the promise of being sent to the front straight away, the New South Wales force saw very little action, their only time under enemy fire being the attack on 3 April 1885 on the rebel stronghold at Tamai, during which three men were slightly wounded. In fact, the soldiers were in far more danger from disease and the first Australian soldier to die overseas, Private Robert Weir, succumbed to dysenteric fever while on board the British hospital ship Ganges, berthed in Suakin, while two others died from typhoid fever.

After little more than a year overseas, the troops returned to Australia, with very little fanfare or recognition. On 17 May 1886 they marched back to the harbour at Suakin and boarded the troopship Arab. The horses they had taken did not make the return trip, but were handed over to the British troops. Arab left Suakin on 18 May 1886, but many of the troops were sick with typhoid and dysentery. Arab was smaller than either of the ships that had carried the contingent to the Sudan, but the men were allowed to sleep on deck to ease the crowded conditions below. When the ship stopped at Colombo on 29 May, twelve of the sickest men were taken to hospital ashore, where three of them later died. From Colombo to Albany, at least one in ten of the men reported for the daily sick parade, and on 9 June the veterinary surgeon, Captain Anthony Willows, died, being buried at sea. After a brief stop at Albany to take on coal, during which no-one was allowed ashore, the Arab reached Sydney on the night of Friday, 19 June. Instead of going to a berth, the vessel anchored and all the troops were put into the quarantine station at North Head, where one more man died.

On the morning of Tuesday, 23 June, the survivors were released from quarantine and taken back to the Arab, which then proceeded up the harbour and berthed at Sydney Cove. The Governor of New South Wales along with the Premier and ministers were waiting to accord the men an official welcome, but the rain was pouring down and the original plan of a march through the city to Moore Park for an official review was cancelled. Instead, the troops marched to Victoria Barracks, where the official speeches of welcome were delivered. A few days later another trooper died, the result of a cold he caught while taking part in the march. As Colonel A J. Bennett, a member of the contingent, later summed up the Sudan campaign, ‘a few skirmishes and many weary marches provided much sweat but little glory.’

Despite the fervour with which they were dispatched to the war zone, the first departure of Australian troops for overseas service is not well remembered today. In fact it is almost forgotten.