During late 1938, the U.S. Army Air Corps saw a need for additional heavy bombardment aircraft and approached Consolidated Aircraft to supplement B-17 Flying Fortress production by Boeing, Douglas, and Vega. When Consolidated president Reuben Fleet was approached, he stated that his company could build a better airplane. Consolidated began design of its Model 32 in January 1939.

By coincidence, Reuben Fleet had been approached by David R. Davis in 1937 to discuss wing-design theory. Not an aerodynamicist, Fleet insisted on having his chief engineer, Isaac Machlin “Mac” Laddon, and aerodynamicist George S. Schairer listen to the proposal. Extensive testing of the design in Cal Tech’s Guggenheim wind tunnel proved Davis’s concept to be far better than expected. The result was a high aspect- ratio wing that offered excellent long-range cruise characteristics. This wing that was applied to the design of the Model 32, which became the B-24 Liberator.

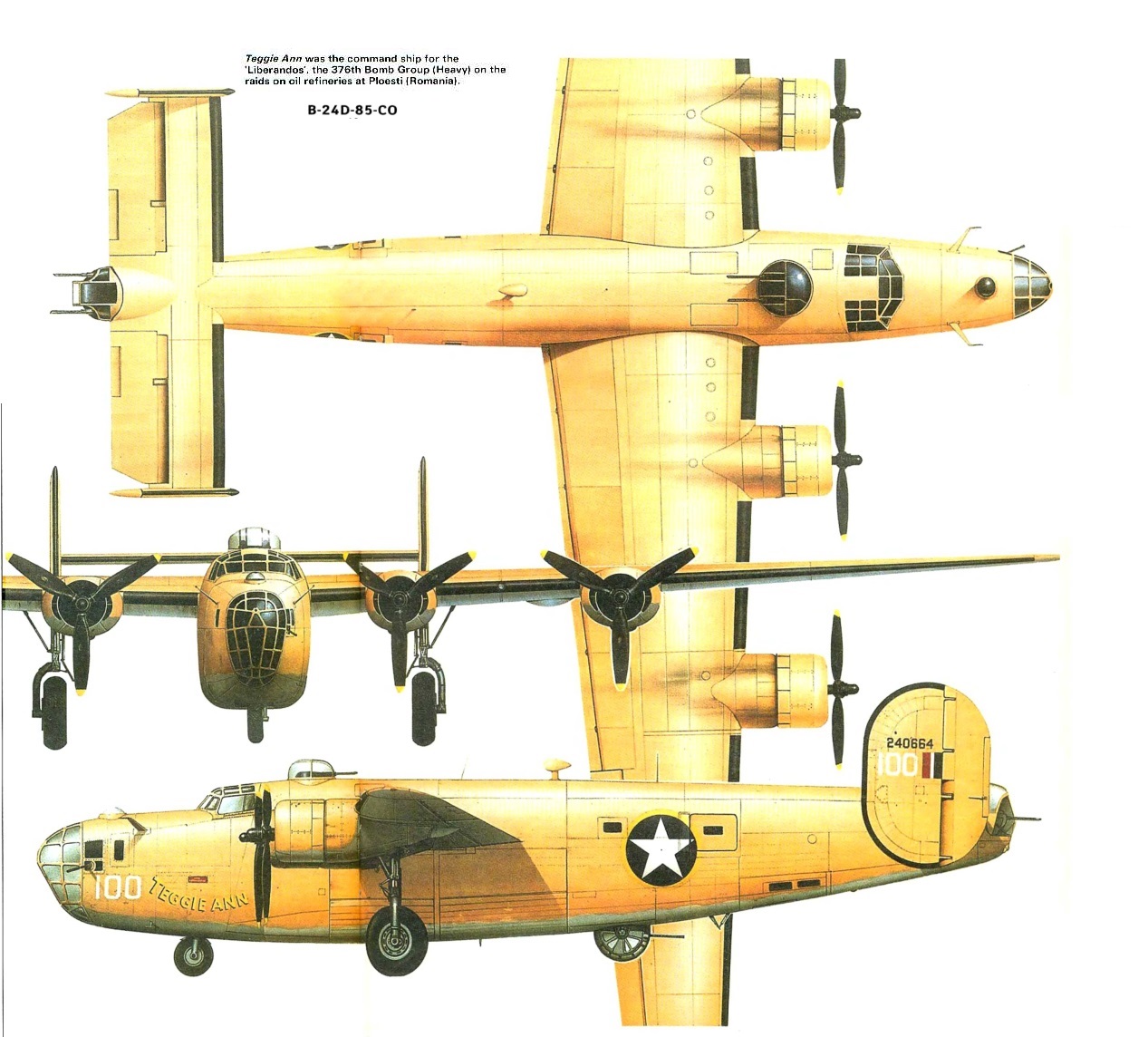

The B-24 was powered by four Pratt and Whitney R-1820 engines. It had an 8,800-pound bombload, a service ceiling of 28,000 feet, a cruising speed of 215 mph, and a range of 2,100 miles. Manned by a crew of 10, the B-24H thru B-24J models mounted 10 .50-caliber machine guns for defensive armament.

The B-24 was a stablemate of the B-17 in the European theater during World War II; however, its vulnerability to battle damage and dissimilar performance compared to the B-17 led Brigadier General Curtis E. LeMay, then commander of the 3d Air Division, to remove the Liberators completely in favor of B-17s. The result was that the 1st and 3d ADs were equipped with B-17s and the 2d AD with only B-24s.

The first raid on the Ploesti oil fields was flown by 13 B-24s from the Halverson Provisional Group on the night of 11/12 June 1942, marking the first Allied heavy bombardment mission against Fortress Europe. On 1 August 1943, the famed Ploesti raid was flown under Operation TIDAL WAVE with a force of 177 B-24s from five bomb groups (three of which were loaned from the Eighth Air Force in Europe).

In the Mediterranean theater of operations, B-24s far outnumbered B-17s. Of the 21 heavy bombardment groups in the Mediterranean late in the war, 15 were equipped with B-24s. The airplanes performed well on the long-range missions deep into Germany and Austria. B-24s did far better in the Pacific theater. The missions were long, over water, with no mountainous obstacles as were encountered in the European and Mediterranean theaters, and enemy resistance was not as intense.

B-24s were also modified for specialized roles as Ferrets, photoreconnaissance platforms, fuel tankers, clandestine operations, and radio/radar jamming.

The B-24 was built in greater numbers than any other U.S. combat aircraft. A total of 19,257 B-24s,RAF Liberators, C-87 transports, and Navy PB4Y-2 Privateers were built at two Consolidated plants as well as Douglas (Tulsa), North American (Fort Worth), and Ford (Detroit). Ford produced 6,792 complete aircraft and another 1,893 knockdown kits that were shipped by road to other plants for assembly and completion.

There is no question that the Boeing B-17 had better press-and a better name- than the Consolidated B-24. “Flying Fortress” evoked a vision of impregnability, while “Liberator” was much more abstract. The B-17 was indeed more of a fortress than was the B-24, but their respective crews defended their aircraft with passion-and in the case of the B-24, with a dash of derring-do attitude.

The B-17 was the older design, conceived by Boeing in 1934, with the first 13 planes delivered to what was then the Army Air Corps in 1938. Consolidated Aircraft Corporation-the 1923 successor to the Dayton-Wright Airplane Company-birthed the B-24 in 1939 as the next generation heavy bomber to supplant the Boeing XB-15, Douglas XB-19 and B-17.

The Lib was faster: 215 mph cruising speed for the B-24J, for example, versus 182 for the B- 17C. The Lib’s gracefully tapered 100-foot Davis airfoil wing (compared to the B-17’s 103-foot-span barn door of a wing) made the difference. The Lib had a larger bomb bay and a somewhat longer range. So it flew faster, farther and carried more bombs than the B-17. I trained on both the B-24 and the B-17 at the aerial gunnery school in Tyndall, Fla. Like my classmates, I fervently hoped to be assigned to B-17s. They were reputedly able to withstand punishment that would down a Lib. That reputation was substantiated by battle damage photos of B- 17s riddled by flak and fighter fire that had still managed to return to base. Not many photos of similarly damaged but surviving B-24s showed up. The Libs didn’t have that big low-aspect-ratio wing to sustain lift after serious aerodynamic damage. Also, enemy fighter pilots had discovered that a concentrated burst into the cross-feed fuel tines between the B-24’s shoulder high wing roots could be fatal.

On the Liberator’s plus side, its tricycle landing gear made taxiing, takeoff and landing easier than the B-17’s conventional tailwheel configuration. The B-24 pilot’s seat was more comfortable too, with its six-way adjustments. A peculiar B-17 drawback was its parking brake control, accessible only to the co-pilot.

With some minor variants, the two bombers had comparable armament: nose turrets (beginning on the B-17 with the G model’s chin turret), top and ball turrets and waist window guns. The tail armament differed: a fully revolving power turret in the B-24, a less mobile turret in the B-17. The B-24’s ball turret retracted fully into the fuselage until it was lowered for action. The B-17’s ball turret rode about three-fourths permanently extended. For a belly landing, the gunner was helped out of his position, after which the ball was jettisoned.

In the event of ditching, there was no contest. That low B-17 wing could serve as a temporary pontoon while the crew scrambled into life rafts. The B-24’s high wing put the fuselage underwater- often badly damaged. Crew members, if they escaped at all, had to swim out.

The B-24, with its big slab-sided fuselage, said one contemporary pilot, “looked like a truck, hauled big loads like a truck and flew like a truck.” As a B-24 passed overhead in plain view, though, it was apparent that the fuselage was narrower, and that long, tapered wing lent the Liberator a deceptive gracefulness. Though more than 19,000 B- 24s were built-more than any other American wartime aircraft-the older, slower but tougher Fortress got the press glory.

In the final analysis, there is no real way to determine if either the B-24 or the B-17 was truly superior. But, the record of the two types indicates that, of the two, the Liberator design was more versatile and considerably more advanced than that of the Flying Fortress. The combat records of both types contradict the assertions that aircrews flying B-17s were “safer” than those in B-24s. The argument as to which was the best can never be settled. As long as there are still two surviving heavy- bomber veterans, one from each type, the B-17 veteran will believe his airplane was best, while the B-24 vet will know better.

B-24s were called Box Cars by crews from their rival B-17s. Other detractors referred to them as Garbage Scows With Wings, Flying Brick, Old Agony Wagon or even more demeaning names. On the ground, the B-24 was an ungainly-looking ship, but airborne with capable, well-trained crews it carved an ineradicable niche in air warfare. The Eighth Air Force in England and the Fifteenth Air Force in Italy flew both B-24s and B-17s.

B-24s are remembered as ships which bombed Rome in July 1943 and a month later carried out the historic low-level attack on Ploesti oil refineries, a raid in which 57 planes with eight to nine crew members were lost.

Notwithstanding its combat record in Europe, the major and unchallenged contributions of Liberators to America’s wartime operations were in the Pacific. In January 1942, Liberators were first flown in action against Japanese held islands. For more than two and a half years, B-24 crews bombed enemy bases, ammunition dumps, and oil storages. By 1943 in the Pacific, Liberators had replaced Fortresses and become work horses for the U.S. Air Corps in its fight against Japan.

The U.S. bombing record could not have been achieved without such aircraft, for costs in lives of young men were high, and squadrons would suffer horrendous losses before perseverance and determination would pay off in final victory.