IN THE FIELD

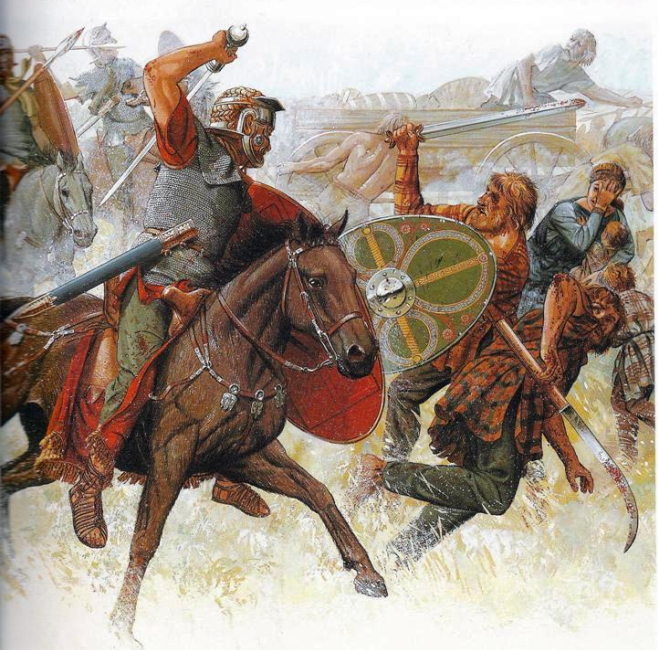

One of the great strengths of the Roman army was the range of available troops, but circumstances dictated which were best in any given situation. Sarmatian cavalry had a reputation for being among the most dangerous and terrifying troops; when they were on their horses they were virtually invincible, unless they had been victorious and were encumbered with booty. ‘Scarcely a line of battle can stand up to them,’ said Tacitus. But when they had to fight on foot they were ‘utterly ineffective’. On one especially vile day in early 69 during the Civil War, 9,000 Sarmatian cavalry of the Rhoxolani tribe took advantage of the Roman civil war by invading Moesia. They were set upon by the experienced Legio III Gallica and its auxiliaries, then fighting for Otho. The frozen ground was becoming soft under a sudden thaw and it was raining. The enemy horses lost their footing. Forced to dismount, the Sarmatians were hopelessly weighed down by the leather body armour which made it impossible to wield their two-handed swords and lances. Trudging through the melting snow they were easy meat for Legio III, especially as the Sarmatians did not use shields. Most were cut down by javelins or by swords, while the rest died from their wounds or as a result of the severe winter weather. In this instance the Roman infantry had turned out to have an enormous advantage over a very dangerous force that might in different conditions have cut them to pieces.

In his account of the Civil War of 68–9, Tacitus provides us with some of the most specific information about how a Roman army might be formed at any given moment. In one example, in the lead-up to the First Battle of Bedriacum (Cremona) in early 69, Otho’s army was made up as follows as it marched towards his rival Vitellius’ forces:

A vexillation of Legio XIII, with four auxiliary cohorts and 500 cavalry, were placed on the left. Three praetorian cohorts in narrow formation held the high road. Legio I advanced with two auxiliary cohorts and 500 cavalry. In addition, 1,000 praetorian cavalry and auxiliaries accompanied them to add force if they won and to act as a reserve if they were in difficulties.

The opening skirmishes showed how unpredictable events could be. Some of the Vitellian forces were able to rush for cover in a vineyard, where the trellises made it extremely difficult for Otho’s men to attack them. They hid in a nearby wood, from which they were able to ambush Otho’s Praetorian cavalry and kill most of them. But the Othonian counter-attack, when it came, turned out to be a success. The Vitellian soldiers had not all been brought onto the battlefield at once; a number had been left in the camp and they mutinied. After the mutiny was suppressed and the forces had regrouped, however, battle was joined: Otho’s army was defeated and around 40,000 men were killed.

LOGISTICS AND PLANNING

There was no sense in running into a fight without first taking precautions. Special tactics in the field, and opportunism, could work wonders. From early on the Romans had shown their capacity for brilliant pragmatic solutions in the field. During the Second Punic War in 213 BC the Roman general Fabius Maximus found the Italian city of Arpi occupied by Hannibal’s Carthaginian forces. Taking advantage of the noise of pouring rain, he sent 600 soldiers with ladders to scale the city walls at points where they were most heavily fortified and therefore least well guarded. Hannibal’s troops failed to hear the Romans, who were able to enter and break down the gates while Maximus attacked another part of the defences. The city soon fell.46

Later, in the Numantine War in Spain in 143–142 BC, Metellus Macedonicus ordered his men to divert a river, having spotted that there was an enemy fort on lower ground. When the river suddenly flooded the enemy camp, the enemy soldiers fled in panic straight into Metellus’ soldiers, who had been lying in wait to ambush them.

A marching army built whatever it needed as it went along. Quite apart from the camps, it also had to build roads and bridges to make sure the supply chain could be maintained. The most famous bridge in Roman military history was Caesar’s bridge over the Rhine, which he ordered to be constructed in 55 BC. Claiming that he had been invited to help the Ubi tribe in their conflict against the Suebi, Caesar decided it was ‘unworthy of his own and Roman dignity’ to cross the river in boats. Nevertheless, the challenge of spanning such a deep, wide and fast-running river was obviously considerable, and daunting.

The bridge Caesar built was a remarkable example of Roman military engineering. It was laid on pairs of timber baulks which were dropped into two parallel rows across the river, separated by the width of the intended roadway. The sides slanted in towards the roadway and were joined across the gap with transoms, braced underneath. The idea, as Caesar proudly claimed, was that the force of the water would actually push the timber more firmly together. Each opposed pair of baulks with its transoms and braces made a single trestle; these were joined together across the river and a roadway laid down on top. Finally Caesar ordered piles to be driven into the river upstream, so that if the enemy tried to throw tree trunks into the river to wreck the bridge these would be prevented from being carried further. Caesar claimed that the entire project took only ten days to complete from the moment the collection of wood began. His description is so precise that it is hard to dispute his version of events.

As soon as the bridge was finished, Caesar’s army marched over, leaving a garrison at either end. The Suebi were sufficiently intimidated to withdraw from all their settlements and prepared to fight a pitched battle. But Caesar said he had done all he needed to. He had ‘struck terror into the Germans’ and saved the Ubi. He pulled back over the bridge after eighteen days, avoiding any further fighting or a major showdown, and ordered it to be destroyed.

Caesar’s achievement sounds remarkable, but perhaps it was not so unusual. The Roman army did such things all the time. In the year 90, Legio III Cyrenaica built a bridge at Koptos in Egypt in the name of Domitian, the work being carried out by Quintus Licinius Ancotius Proculus, the praefectus castrorum, and Lucius Antistius Asiaticus, the prefect of Berenice, under the care of the centurion Gaius Julius Magnus. It was just one of the countless bridges built by the army for its own use and that of civilians. Over a century afterwards, Cassius Dio said that ‘rivers are bridged by the Romans with the greatest ease, because the soldiers are always practising bridge-building, which is carried on like any other warlike exercise’, although Vegetius later recommended though that learning to swim was essential for soldiers because some rivers were unbridgeable: a pursuing or fleeing army might need to cross one in haste.

Caesar’s imaginative solutions to logistical problems reached a particularly revolting height at Munda in 45 BC during his Spanish campaign. Short of timber when he needed to build a rampart, he had plenty of enemy corpses:

Shields and javelins taken from among the weapons of the enemy were placed to serve as a palisade, dead bodies as a rampart. On top, decapitated human heads, impaled on swords, were set out in a row facing the town, the purpose being not only to surround the enemy with a palisade, but also to give him an awe-inspiring spectacle by displaying before him this evidence of valour.

In 57 BC Caesar was assaulting the fortified stronghold of the Gaulish Aduatuci tribe. To begin with his soldiers were fought off. He therefore ordered his soldiers to start building siege machines. The Roman troops cut down trees, prepared the timber on the spot and assembled the machines before the enemy’s eyes. This single occasion shows the Roman army’s astonishing ability to create the equipment it needed to outclass an enemy from what was available in the immediate vicinity. Moreover, the men involved almost certainly knew what to do without having to resort to manuals. But such books certainly existed. Under Augustus, not many years later, Vitruvius wrote a treatise on architecture that included a section on how to build siege equipment such as mobile towers and the ‘ram tortoise’, following one devoted to the construction of artillery. He provided instructions and measurements of the components.

Not having the slightest idea what they were, the Aduatuci made fun of the sight of Caesar’s siege machines as they were manufactured. The smiles were wiped off their faces when they saw heavily armed Roman soldiers advancing towards the Aduatuci fortifications in the devices they had constructed. The result was panic. Attempts to appease the Romans followed, accompanied with offers of provisions. It was a trick. Waiting until they saw the siege machines standing idle and unmanned, the Aduatuci attacked the Roman forces at night. But Caesar was waiting. The Aduatuci were beaten and the whole population sold into slavery.

HEROES

Great awards awaited soldiers who pulled off remarkable feats. Spurius Ligustinus, a loyal old soldier of the Republic, proudly told his fellows in speech in 171 BC how he had been decorated thirty-four times and received the corona civica (‘civic crown’) six times for saving the life of fellow Roman citizens. Such honours did, however, depend on the man’s background, and on who was giving out the decorations. In around 46 BC, during the Civil War an opponent of Caesar’s called Caecilius Metellus Scipio was handing out awards to soldiers who had excelled themselves. His associate, Titus Labienus, recommended that one particularly brave cavalryman deserved a gift of gold bracelets. Metellus Scipio declined on the grounds that the man had recently been a slave, and that the award would thus be degraded by giving it to someone of such lowly origins. When Labienus took gold from the booty captured in Gaul and gave it to the cavalryman concerned, Metellus was not to be outdone and said ‘you will have the gift of a rich man’. Enticed by this, the trooper threw the gold back at Labienus. Metellus then said he would give the cavalryman silver bracelets; the soldier was delighted, preferring the glory of a decoration awarded by the commander to the intrinsic value of the gold.

In the reign of Nero, one old soldier’s brilliant career was set down in stone. Marcus Vettius Valens was a successful Praetorian guardsman who had the opportunity to travel all the way from Rome to take part in the invasion of Britain in 43, while serving as a beneficiarius on the personal staff of the praetorian prefect. His career was recorded in an inscription set up at Rimini in Italy in 66, during his later life, proudly proclaiming that in Britain he had been awarded necklets, armlets and medals for his achievements. He seems to have stayed on, despite reaching the end of his 16-year service term, winning a gold crown too. Later in his career he rose to the rank of centurion in Legio XIIII, not long after its success in the war against Boudica in 60–1. He must therefore have met some of the legionaries who fought in the final battle that destroyed the most serious provincial rebellion in Britain’s history.

Gaius Velius Rufus, primus pilus of Legio XII Fulminata, was awarded the corona vallaris, the ‘rampart crown’, along with collars, medals and armlets, by Vespasian and Titus for being the first man over the walls during the Jewish War of 66–70, though this did nothing to repair the legion’s tarnished reputation. Nearly two decades later Velius Rufus was decorated again for his part in sieges during the war against Central European tribes including the Marcomanni. His remarkable career, which included other honours and military commands, was commemorated on an inscription set up at Baalbek in Syria.

During the assault on the temple in Jerusalem towards the end of the Jewish War several Roman soldiers individually performed remarkable deeds. Pedanius was an auxiliary cavalryman in pursuit of retreating Jewish fighters who had attacked the Roman camp, He leaned down as he rode into them and managed to grab a fully armoured soldier and pull him up. With the prisoner grasped in his hand, Pedanius presented him to Titus, who ordered the captive’s execution.

The Jews were able to field their own heroes. A man called Jonathan once presented himself in front of the Romans and challenged them to single combat. One of the other auxiliary cavalrymen, named Poudes, stepped out and ran to fight Jonathan until he fell and was killed. The triumphant Jonathan mocked the Romans, swaggering over his kill, until an arrow fired by a centurion called Priscus killed him too.

Another hero of the Jewish War was a Syrian auxiliary called Sabinus. He was so small and lean it was a surprise to everyone that he was a solder. His size was completely out of proportion to the heroism he showed. After the Jewish stronghold of Antonia was attacked, Titus exhorted the army to face the challenge ahead, pointing out that the first man to scale the wall – if he survived – would be ‘envied by others’ thanks to the rewards that he, Titus, would give him. Sabinus was the only one to speak up:

‘I readily surrender up myself to you, Caesar. I will ascend the wall first. And I heartily wish that your fortune may follow my courage, and my resolution. And if some ill fortune grudge me the success of my undertaking, take notice, that my ill success will not be unexpected; but that I choose death voluntarily for your sake.’

Eleven men were inspired to follow Sabinus as he led the way, his shield over his head, while missiles were fired at them and stones rolled down the slope. Three of the eleven were knocked over and killed but Sabinus kept going. He reached the top of the wall and maintained his attack, to the amazement of the Jews. Eventually he was isolated; having fallen over, he struggled back up, held his shield aloft and fended off his attackers, continuing to wound some of them until finally he was overwhelmed and killed. The other eight, all wounded, were rescued and carried back to the Roman camp.