PHILIPPI: TRICKERY, BRAVERY AND SUICIDE

Playing tricks on the enemy was an excellent way of seizing the advantage, but it could have unforeseen consequences. In October 42 BC at Philippi, two years after the assassination of Julius Caesar, Antony and Octavian were determined to force Caesar’s killers Brutus and Cassius into fighting a battle. In the end they fought two. Antony’s idea was to have his men set up all their standards every day so it would look as if his entire army was in battle order, ready for the fight. It was a ruse. In reality an area of marshland lay between Antony and the enemy. Some of his troops were in the meantime working their way through the marshes to cut down reeds and build an earthen causeway embanked with stones, using piles to make their way across the deeper places. This all had to be done in complete silence, although Antony had the advantage that Brutus and Cassius’ men were prevented by the reeds from spotting what was going on. After ten days Antony was able to send part of his army through to take up position and build redoubts (small fortifications) to reinforce their positions.

This of course gave the game away. Now Cassius knew what was happening. He was impressed and came up with the idea of secretly building a wall and palisade at right angles across Antony’s causeway to cut off the advance force. It was an ingenious solution which enraged Antony when he discovered what had happened. He impulsively organized a charge, his men carrying tools and ladders, to bring the wall down and attack Cassius’ camp. Meanwhile, Brutus’ troops were watching, equally outraged ‘at the insolence’ of Antony’s attack. They dived in without orders and killed as many of Antony’s soldiers as possible, before turning on Octavian’s army and causing it to run away, destroying Legio IIII in the process. Shortly afterwards they had Antony and Octavian’s camp.

Antony kept up the attack in a reckless assault of exceptional bravery. He had Cassius’ palisade torn down and its accompanying ditch filled up, killing the men on its gates and dashing forward under a hail of missiles. The men who had been working on the wall for Cassius were driven off and Antony headed for their camp. Cassius had failed to put more than a token guard on his camp, so Antony’s men soon took it. The two sides both ended up in much the same position, but in the confusion neither was aware of what had happened. Antony had taken Cassius’ camp, while Brutus had taken Octavian’s. ‘There was great slaughter on both sides’, said Appian, Cassius losing 8,000 men and Octavian 16,000. In his shame Cassius ordered one of his freedmen to kill him. The First Battle of Philippi was over.

On the same day, reinforcements were being brought from Italy to bolster Octavian and Antony’s army against Brutus and Cassius. Domitius Calvinus was bringing two legions, including one known as Legio Martia, as well as 2,000 members of Octavian’s personal praetorians, four cavalry wings and other unspecified troops. As they sailed across the Adriatic in troop transports they ran into an enemy naval force of 130 ships led by Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus and Statius Murcus. The wind dropped and the transport ships were suddenly trapped. Ahenobarbus and Murcus sent their warships in and annihilated most of the transport ships. The beleaguered soldiers tried tying their ships together with ropes but Murcus ordered a hail of burning arrows to be fired, forcing the men to untie the ships again. Realizing there was no hope, the legionaries and other soldiers were furious at the thought of suffering pointless and humiliating deaths. Those of Legio Martia acted with particular bravery. Some took their own lives, others leapt across to the warships in suicidal attempts to fight back. In the event many men drowned or were washed up on the shore, while a large number capitulated and went over to the tyrannicides. But it was Legio Martia that was remembered that day.

Meanwhile Octavian and Antony were in a bad way. The naval disaster was bad enough, but they were also running short of food and were desperate to force Brutus to fight. Brutus had no intention of obliging – he knew he had the upper hand – but his soldiers disagreed. They wanted a battle, believing that being kept back amounted to being ‘idle and cowardly’. So did their officers, who thought the men were so whipped up that there was a good chance of victory. It was the officers who convinced Brutus he would have to fight, while Brutus was becoming worried that his men would go over to the enemy.

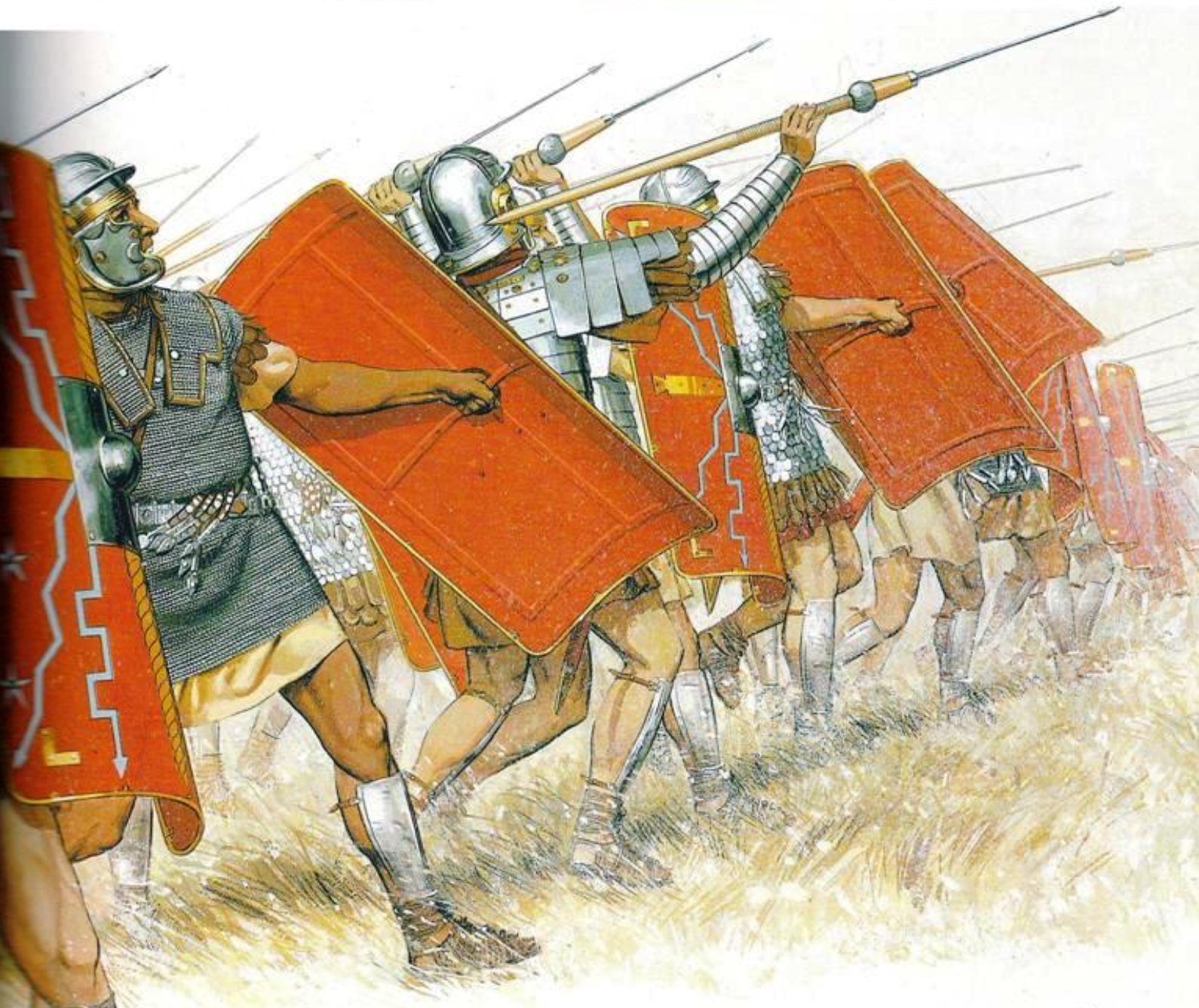

The battle, when it started, was a vicious close-combat affair with little in the way of missiles ‘which are customary in war’. Instead the men killed each other with swords: ‘The slaughter and the groans were terrible’. The dead were carried from the field to clear a space for reserves to march forward. When Octavian’s men eventually pushed Brutus’ army back into a steady, ordered and disciplined retreat which accelerated in speed, it was over. Brutus’ army was routed but he escaped with four legions. The following day he ordered his friend Strato to kill him.

Later judgements varied. Valerius Maximus said Brutus had ‘murdered his own virtues’ before assassinating Caesar and that he had permanently associated his family name with ‘abhorrence’ (Lucius Junius Brutus, his ancestor, had been one of the most prominent men who threw out the last Roman king and established the Republic in 509 BC). On the other hand, Appian called Brutus and Cassius ‘two most noble and illustrious Romans’ whose virtue was incomparable but for their one crime.

The same could be said of many of their men, and those of Octavian and Antony, who fought two extraordinary battles exhibiting remarkable bravery, fortitude and discipline. Their victory set Octavian on the path that would lead in 27 BC to his becoming Augustus Caesar.

CORBULO IN ARMENIA

Simply being on campaign could involve extraordinary levels of hardship, especially where remote territory and barbarians were part of the mix. In the reign of Nero two remarkable wars, only two years apart and on opposite sides of the Empire, found two of Rome’s greatest generals facing their greatest challenges. Both overcame adversity in different contexts by relying on their leadership skills and the training and discipline of the men under their command.

In 59 the general Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo was leading the III Gallica, VI Ferrata and X Fretensis legions and their auxiliaries into Armenia to recover Rome’s control over the region from the king Tiridates I. It was a bitter and piercing winter but the soldiers were camped out in tents made only of hide. To set the tents up the troops had had to cut through the ice that covered the ground and dig out pits into which they could erect them. The cold was so extreme that some died while standing out on watch. Tacitus alleged that ‘one soldier was seen carrying a wood bundle whose hands were so deeply frozen that they stuck to his load and dropped off from the stumps of his arms’. Corbulo was forced to go about his men wearing only light clothing and without any head covering in order to bolster their spirits. He was not entirely successful. The climate was so severe and the duties so onerous that some deserted. As a result Corbulo instituted a zero-tolerance policy: any deserter, even a first-time offender, would automatically be executed. The desertions did not stop, but they were markedly reduced.

Arrogance and a lack of discipline had nearly wrecked the campaign, but discipline and organization would later achieve great things. Corbulo decided that the legions would have to stay in camp until spring. He distributed his auxiliary troops in various strongholds and placed them under the command of a primus pilus called Paccius Orfitus. A man of Orfitus’ experience, who had gained Corbulo’s trust, ought to have been totally reliable. He turned out not to be. Keen to fight, he wrote to Corbulo to tell him that the enemy was being incautious and that the chances of a successful attack against the Armenians were therefore excellent. Corbulo to him to hold his fire and wait until reinforcements arrived. Orfitus took no notice. When auxiliary units turned up begging to be allowed to fight, he took them out to give battle. His defeat was total. Although he escaped, the remaining troops were completely demoralized and terrified. Corbulo was so angry he ordered Orfitus, the commanders of the auxiliary units and the men to camp outside the fortifications until the rest of the army pleaded for them to be let back in.

As the campaign progressed, Corbulo became frustrated by what Tacitus called a ‘roving enemy’ that avoided either negotiating peace or facing the Romans on a battlefield. This was the sort of foe the Romans, who always preferred set-piece battles, hated. Corbulo had managed to fend off Armenian attacks on his supply routes by placing forts at key spots. He decided that he would have to bring the war to the Armenian strongholds. The climax was to be an assault on the city of Artaxata (modern Artashat). Corbulo’s legions were unable to cross the river Araks by the nearest bridge because it was so close to the city they could be hit by Tiridates’ defenders, so they had to take a circuitous route via a ford some distance away.

But Tiridates too had a problem. The city was difficult to defend, and any attempt to prevent the Romans blockading Artaxata would result in his cavalry foundering on impassable ground. He decided therefore that he would have to present Corbulo with the opportunity for a battle. That would either mean confronting the Romans or pretending to retreat and tricking them into pursuit. Corbulo had organized the legions so that they could either march or fight. Tiridates surrounded the Roman column, which was arranged with the best of Legio X’s soldiers in the middle, the VI on the left and the III on the right, with 1,000 cavalry at the rear who had been given strict instructions not to be lured into chasing an Armenian retreat. Infantry archers and more cavalry were on the edges of the columns; these were presumably all auxiliaries.

Tiridates’ tactics were to harry the Romans in an attempt to break up the formation. He achieved nothing. The Romans were, ironically, helped when a cavalry officer, advancing too far on his own, was ‘transfixed by arrows’ fired by the Armenians. That focused the attention of the other Roman soldiers on staying where they were. The day’s fighting was ultimately inconclusive and Corbulo ordered his men to make camp where they were. He toyed with the idea of blockading Artaxata that night, believing that Tiridates was holed up there. However, his own scouts discovered that Tiridates had set out on a longer trip elsewhere. In the morning, when Corbulo surrounded Artaxata, the inhabitants realized their best chance was to surrender and save themselves. They opened the gates and let the Romans in. Knowing he could not commit enough troops to hold it, Corbulo ordered the city to be burned and razed to the ground.

Corbulo’s Armenian war was far from over. In 60 he headed for the capital Tigranocerta. Progress was a struggle because of the heat and a shortage of water, and Corbulo himself was nearly assassinated by an armed Armenian. Fortunately, when he reached Tigranocerta the city surrendered and he was able to place a Roman client (and puppet) king, Tigranes VI, on the Armenian throne. Hostilities were to resume only two years later when the Parthians arrived to attack the city, but for the moment Corbulo’s remarkable campaign had shown what the Roman army could achieve – and, in this instance, without ever fighting a pitched battle.

SUETONIUS PAULINUS AND THE BOUDICAN WAR

At almost exactly the same point of Nero’s reign another war broke out on the other side of the Roman Empire. Also involving several Roman legions, auxiliary forces, and a very experienced general, it came close to total disaster. The difference this time was that the Romans were caught unawares by a major rebellion when their garrison was widely dispersed. The setting was Britain, seventeen years after the conquest had begun in 43. Four legions – II Augusta, VIIII Hispana, XIIII Gemina and XX – were stationed in Britain at the time, as were at least the same number of auxiliaries, made up of infantry and cavalry. The legions were distributed around the province, such as it was by that early date: Legio II Augusta was at Exeter, VIIII Hispana at Lincoln, XIIII at Wroxeter and XX at Usk in south Wales. They and the auxiliaries amounted to one of the greatest concentrations of Roman forces in the entire Empire at any time. The distances between locations were not great, but Britain’s undeveloped state, its forests and numerous rivers, made it difficult to move fast, even though a road network radiating out from the new trading settlement of London was well under construction.

The governor, Suetonius Paulinus, who arrived in Britain or around the year 59, was determined to crush resistance once and for all. A highly experienced general, he was considered to be a rival of Corbulo’s, both in terms of his military skill and his popular reputation. Paulinus identified the source of the problem as the native Druid priesthood, to whom all the tribal leaders deferred, and who were provoking rebellions and risings from their headquarters on the island of Anglesey just off the north-west coast of Wales. To make the short and shallow crossing from the mainland, the Roman infantry needed flat-bottomed boats and fords had to be found for the cavalry. Doubtless Paulinus thought the campaign would be quick, brutal and easy.

Sailing across to the island was one thing. None of the Roman soldiers was, it seems, ready for what confronted them. They found armed warriors waiting, and mixed among them women dressed in black as furies, running around with torches, their hair streaming behind them. The Druids were also present, raising their hands to the sky and chanting incantations. This was so far outside the Romans’ experience, either hitherto in Britain or on the Continent, that they were paralysed with fear. Paulinus had to urge them on by pointing out that they should not be scared of ‘women and fanatics’. The Romans pulled themselves together and advanced. For all the Britons’ noise and dishevelled hair they were hopelessly outclassed. The Romans easily cut down the warriors, the Druids and the women, and used the Britons’ own torches to set them on fire. The island was garrisoned and ‘the groves sacred to their savage rites cut down’. What seems to have provoked the Romans’ disgust was the discovery that the Druids had indulged in human sacrifice of their prisoners in order to use the entrails to communicate with their gods. If the Romans thought they had exterminated the problem, they were wrong. Dispatches from the other side of Britain soon brought news of a major rising in the east of the province.

The Iceni tribe of East Anglia had always been a serious problem for the Romans, but relations had settled down under the client king Prasutagus, who had come to an accord with the Roman government of Britain. Prasutagus knew that the Romans were more powerful and believed that if he made Nero, along with his daughters, his heir, his kingdom would be safe after his death. He was wrong. Centurions had been placed in charge of the region’s civilian administration, performing tasks such as policing and the collection of tribute. Now these men spotted an opportunity to cash in when Prasutagus died, probably in 59. With the help of imperial slaves, they started ransacking the tribal lands, stealing estates and plundering property ‘as if they were spoils of war’. For good measure they flogged Prasutagus’ wife Boudica and raped her daughters, treating the family’s relatives as if they were slaves. The Iceni, not surprisingly, rose up in rebellion, almost certainly with backing from the Druids.

The Iceni were joined by a neighbouring tribe called the Trinovantes, whose ancestral lands were in the vicinity of a new colony at Colchester, formerly occupied by Legio XX. The soldiers had been moved out around 47 and the colony established among the remains of the short-lived legionary fortress. With the typical and tactless arrogance of an invading army that looked down on the defeated as lesser beings, the veterans had enthusiastically helped themselves to Trinovantian land, urged on by serving soldiers who were hoping to do the same when they were discharged. The Trinovantes were already under pressure. Before the Roman invasion another tribe, the Catuvellauni, had taken control of their territory. After the invasion some of the Trinovantes had also been forced to spend their estates on funding compulsory priesthoods in the cult of the deified Claudius, founded at Colchester after his death in 54, while others may have done so voluntarily in the belief they would gain an advantage under Roman rule. Either way, it appears that some of them had borrowed money from Roman speculators to finance these positions. When the loans had been abruptly called in, some of the senior tribesmen faced ruin.

It was not entirely surprising that the veterans behaved as they did. Roman legionaries had been encouraged to believe they were entitled to such privileges since the time of Augustus. Neither had the complacent colonists bothered to construct any new defences, an extraordinary oversight for military veterans for which they would pay dearly.

The notorious attack on Colchester soon followed. Knowing that Paulinus was too far away to help, and with time running out, the desperate colonists sent an emergency dispatch to the procurator of Britain, Catus Decianus, who was probably in London. His response turned out to be hopeless. He sent about 200 ill-equipped men to join the small unit of serving troops still based in Colchester. A few hundred Roman soldiers found themselves confronting a horde of tribal warriors that numbered thousands, without the slightest hope of relief. The soldiers, veterans, and colonists barricaded themselves inside the temple of Claudius, unable even to build a defensive ditch around the building and hoping that the structure would be enough to protect them. It was not. The Iceni and Trinovantes first burned the settlement to the ground and then turned their attention to the temple. The building and its terrified defenders held out for two days but the end was inevitable. The entire population of the colony was massacred.

Enough time had passed for news of the emergency to reach Petilius Cerealis, then commanding Legio VIIII Hispana somewhere near Lincoln to the north. Cerealis headed south-east to find the rebels, but there were so many that thousands of his infantry were wiped out on the spot. Only he and his cavalry escaped. With one legion effectively incapacitated, the effective garrison of Britain had suddenly been cut by around a quarter, while one of the gravest crises in Roman provincial and military history was still taking shape. With an eye to his own survival, Catus Decianus abandoned Britain and headed for Gaul. If the revolt really did involve around 120,000 rebels, as Dio claimed, then he could be forgiven for believing all was lost.

Paulinus immediately abandoned the campaign in Anglesey when he heard the news which must have been brought to him by mounted military messengers. He had with him Legio XIIII Gemina and all or part of Legio XX as he headed down Watling St towards London in an effort to cut off the rebels. He sent orders to Legio II Augusta in Exeter to join him. London had no official status at that date but it was a major river crossing over the Thames as well as a road junction, and was rapidly developing into an important commercial centre. Paulinus seems to have hastened ahead to find out what was going on. He realized he had no choice but to abandon London and St Albans (Verulamium: the next city along Watling St as he retreated to the north-west) and their inhabitants to their fate, apart from those who were mobile enough to join him. The rebels were focusing their attention on killing as many people as possible and on amassing loot. It was a fatal error. Their indulgences were beginning to slow them down, when it had been speed that had given them the initial advantage.

Paulinus had, according to Tacitus, around 10,000 men. Together with Legio XIIII and part of Legio XX he also had some auxiliaries, all of which had been with him in Anglesey. These men had been following on behind him when he took his advance mounted force to London. Having abandoned London and St Albans, Paulinus met up with them somewhere in the Midlands and prepared for a final battle. In order to compensate for his lack of numbers, he chose to station his forces in a narrow gap with higher ground on both sides, while a wood to the rear would inhibit the Britons’ chances of ambushing him. His men faced out across an open plain where the battle could be fought, with the cavalry on the edges. The Britons swaggered around, buoyed up with confidence and weighed down with loot. They brought their women with them and placed them and their booty-packed wagons around the edge of the plain. Remarkably it is only at this point in Tacitus’ account that Boudica appears as the leader of the Britons, rallying her army from her chariot with her daughters urging her fighters to vengeance which would have to be achieved if they were to avoid enslavement. Dio, however, said she led and directed the whole war.

Paulinus started the battle by ordering a launch of javelins, followed by a steady advance in wedge formation. If Tacitus can be believed, the Britons lost control almost immediately and started to beat a hasty retreat, only to run into their own wagons which prevented them escaping. The Romans had the day from that moment on, mowing down both warriors and women, and killing the baggage animals so the survivors could not dash away. The losses were colossal, though the figure of 80,000 Britons allegedly killed by the Romans is implausibly high; only 400 Romans were said to have died, with a few more wounded. This figure is a little more believable but neither total should be taken literally. They were supplied to provide the impression of a massive Roman victory, which indeed it was. Nevertheless, the battle was close-run, and even closer-run because Legio II Augusta had not joined in. The legion appears to have had no commanding officer at the time, and instead was in the charge of its praefectus castrorum, Poenius Postumus. Postumus had refused to march the legion from its base to join the war, probably out of fear. He committed suicide as the only reasonable course of action open to him, a humiliating end to what must have been a significant and successful career.

In the aftermath, said Tacitus, 2,000 legionaries were sent over from Germany, along with eight auxiliary cohorts and 1,000 cavalry. These helped bring Legio VIIII back up to strength so it could participate in a punitive campaign to punish the other tribes and crush any further resistance. Evidently it had not been wiped out as Tacitus had claimed earlier. Legio XIIII Gemina was awarded the title Martia Victrix and strutted into the future bearing that name for all time. Its ‘men had covered themselves with glory by crushing the rebellion in Britain’, said Tacitus. Nero decided they were his best troops. A few years later the legion would leave Britain and play a major part in the civil war of 69, returning briefly before being permanently reassigned in 70 to bases on the Continent. Legio XX may have been given the name Valeria Victrix on this occasion, though that is less certain. The sad fact is that virtually nothing is known for certain of the men who served in Legio XIIII at this time. The few tombstones that survive at the legion’s Wroxeter base all seem to precede the Boudican War, commemorating men carried off by death before the legion’s moment of glory.