Dresden, flying a white flag, moments prior to her scuttling.

Before the war, Germany had devoted considerable study to the damaging blows which could be made against Britain through attacking the vital trade routes. It was, however, fully appreciated that the task of getting through to the Atlantic, and so to the other highways, would always be difficult when once hostilities had begun.

There were but two methods practicable. If one of her regular naval cruisers attempted to burst through the blockade by force, she would be handicapped from the first: she would be too blatant, too obvious. For, whilst a merchantman can become a disguised warship, it is not always possible to change the appearance of a man-of-war in order to make her resemble a passenger or cargo vessel. (It is true that during the war two or three of the British naval sloops were altered to suggest traders, but they were not a great success and did not always deceive the enemy.) When a cruiser has four, or even three funnels, war-like bow, low freeboard, and conspicuous guns, but a forebridge without any of the high decks of a liner, no amount of paint can fool a seafarer into believing her innocence. Therefore the chances of genuine cruisers running the blockade were rightly considered remote. We have seen that Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse and Berlin succeeded because the blockade patrols were not yet of sufficient strength, and these two raiders went hundreds of miles out of their way. But they were also dressed to conceal their true character, prepared to pretend and bluff; and this second method quite definitely was accepted by the German Admiralty as the only means of sending surface cruisers forth when the other genuine cruisers had ceased to exist.

It remains an interesting fact that not one of the latter throughout the whole four years made the slightest effort, either independently or in company, to rush the Dover Straits or get westward of Scotland. At the time when the Canadian convoy was coming over the Atlantic there certainly were both anxiety and a half-expectation at the British Admiralty that German battle-cruisers might break through and do their direst. It would have been a gamble, but certainly a justifiable risk. Transports full of soldiers are always most attractive targets in their helplessness; and it would have been of direct assistance to the German Army if some thousands of British troops could have been shelled or drowned. Whether all the battle-cruisers would have got back to Germany again is quite another consideration.

It may be stated at once that after Berlin’s meteoric career concluded at Trondhjem, not even a merchant cruiser got out from Germany to the ocean routes again until January 1916. No blockade line between Scotland and Iceland, or Scotland and Norway, can ever be absolutely impenetrable having regard to long dark nights and days of fog. The very few raiders which did pierce this steel ring certainly deserved some reward. Only when these attempts were made by exceptionally brave and determined commanding officers, who had the patience and endurance to go near the Arctic Circle, the care to make the best of nocturnal and meteorological conditions, and the luck of not being discovered lower down the North Sea, was attainment possible.

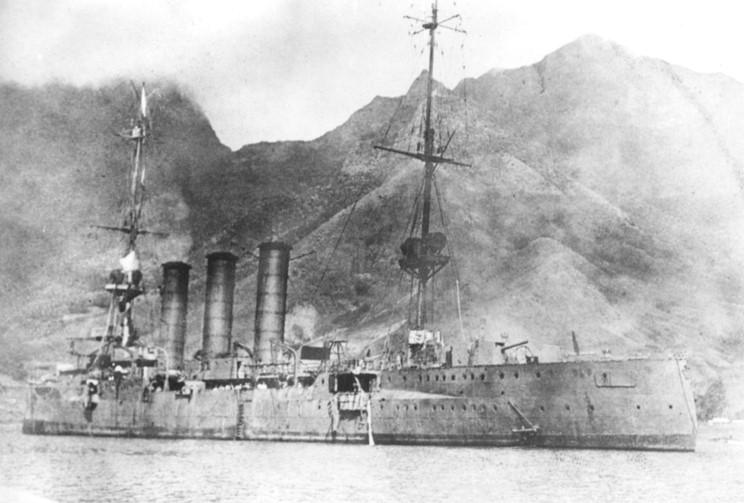

During the first months of hostilities, then, Germany’s units for waging war along the commercial sea-routes consisted of (a) those of her regular cruisers which happened to be on the China or West Indies stations, and (b) any of her ocean liners which happened to be in foreign waters. It will now be our interesting inquiry to follow one of the most amazing voyages in all records of the sea. Let us open the map at the West Indies, which are so richly endowed with colourful background and memories of maritime rovers. It will help us to vitalise the story if we try to visualise the small German cruiser Dresden, which was a sister-ship of that famous raider Emden. At the beginning of the war Dresden was six years old, and still capable of about 24 knots. Armed with ten 4.1-inch guns, she had three tall thin funnels, two tall masts (with searchlight platforms), and displaced 3544 tons. Her maximum coal capacity was 850 tons, a factor which was to have an important influence on her adventures; and her engines were turbines. Captain E. Köhler was her commanding officer.

Steaming across from Germany to the Caribbean came the cruiser Karlsruhe, a bigger vessel, of 4820 tons, with a speed of over 27 knots. She was armed with twelve 4 1-inch guns, had been built only that same year, and was under the command of Captain Lüdecke. A lean, four-funnelled, low-lying ship with a modern bow, and every line of her suggesting speed, this two-master was coming out to relieve Dresden, but the two captains were to change over. Dresden was then to return home and have a much-needed refit. This is a second factor which will presently gain greater significance. It was at Port-au-Prince, Haiti, that the two cruisers met and on July 25 the respective captains took over from each other. Our immediate concern being Captain Lüdecke’s cruise in Dresden, we must postpone the career of Karlsruhe till a later chapter.

It was on July 28 that Dresden left Port-au-Prince and went on to the Danish Island of St. Thomas in order to coal her bunkers before starting for Germany. This little hilly islet of only 33 square miles, with poor soil, occupies considerable strategical importance which has become even more marked since the Panama Canal was opened. Nature has made it one of those key-positions of the sea where four important routes converge. It is the centre whence radiate the tracks to New York and Boston, the Mexican Gulf, the eastern ports of South America, and Colon for the Panama Canal. When aerial travel becomes more firmly established it will doubtless increase the value of St. Thomas still further. But in 1914 it was, as we have noticed, one of the German supply centres, and here indeed the Hamburg-Amerika Line had its offices. If it was little more than a port of call, yet its harbour is one of the finest of all the West Indies, excellently placed for raiders to come in, coal quickly, and then on putting out to sea find themselves already on the highway of commerce.

By July 30 European political affairs were advancing towards a crisis, but on the next day Dresden steamed out of St. Thomas north-eastwards for the Azores and English Channel. She had not been gone more than three hours when she picked up a wireless message from Porto Rico ordering her not to return home but carry on cruiser warfare in the Atlantic: that is to say, she was to destroy enemy commerce. She was ideally placed with the choice of routes, and no raider could wish for a better beginning. Here she was, already at sea, beyond territorial waters, bunkers full, too far from land to be spied on, but supposed to be making for mid-North Atlantic.

As a matter of fact she turned south and wisely began cruising down the track of shipping bound up from South American ports. Not many days had she to wait. It was erroneously reported that she was off New York, though in truth on August 6 she had passed the mouth of the Amazon and off Para stopped her first ship. This was the British S.S. Drumcliffe, 4072 tons, from Buenos Aires in ballast on her way to Trinidad for fuel. A boarding-party was sent to her, but Drumcliffe’s master had with him both wife and child, who would be an inconvenience aboard the cruiser if the merchantman were now destroyed; and it would be useless to take the steamer along, seeing that she was in need of coal. After the steamer’s wireless had been destroyed, and a declaration signed pledging officers and crew not to take part in hostilities against Germany, Drumcliffe was dismissed.

Just over an hour later appeared the British S.S. Lynton Grange, 4252 tons, bound for Barbados, and the same experience happened to her. But in the meantime arrived the British S.S. Hostilius, 3325 tons, bound for Barbados also, and then the extraordinary situation occurred of captain, officers, and crew all refusing to sign the German declaration, yet Captain Lüdecke at 7.40 p.m. released her because he did not think her destruction worth while. Dresden then proceeded still on her south-east course towards Rocas Reef, which lies singularly isolated, about 130 miles off Cape San Roque, and just off the position where the north-west track for Barbados and St. Thomas separates itself from that to the Cape Verdes and Canaries. It is worth while calling attention to it at this stage, as Rocas was one of the secret rendezvous for German raiders and likely to become of the greatest convenience.

After cruising about the crossways for a few days, she must needs coal, and such was the good organisation of the Supply Officer that she was now able to enter the little-known, rarely frequented harbour of Jericoacoara, a Brazilian inlet which lies just west of the 40th meridian, between Cape San Roque and Para. There she led the S.S. Corrientes, from which she took 570 tons of coal. This supply ship had been waiting in Maranham, a port which is a little further westward, but had been summoned by Dresden’s wireless and got under way at 6 a.m., August 8, meeting Dresden the same afternoon. The operation of coaling occupied August 9-10, after which the two ships in company went to the north of Rocas Reef and Fernando Noronha, having thus intentionally crossed both the north-west and north-east trade routes, but so far with no reward.

Fernando Noronha is another Atlantic island which gives picturesque background to the raiders’ story. Lying about 80 miles east of the Rocas Reef, it is only 7 miles long by 1½ wide. We can picture this volcanic settlement as a collection of gaunt rugged rocks, over which the hot tropical rains and against which the smashing thunderous seas beat. Ashore there is nothing lovely in the stunted trees, the 700 convicts of assassins and others who long to escape. But the island boasts of cable and wireless station, and in recent years since the war aeroplane flights between Europe and South America have halted here. Liners do not call, but give a wide berth to these bare rocks and shark-infested blue waters.

Now, on the day before she met Corrientes, Dresden was still further being provided for. The Hamburg-Amerika collier Baden on August 7 with 12,000 tons of coal had reached Pernambuco, which, of course, is only a few hours’ steaming from Cape San Roque and therefore excellently situated in regard to the two sea-tracks. So, having spent some more unprofitable days hovering about, Dresden sent Baden an order to rendezvous near Rocas Reef. This signal was wirelessed through Olinda, the telegraph station which is close to Pernambuco, and out came the supply ship. The perpetual anxiety of every raider’s captain was the frequent necessity of having to meet, without fail, some undefended slow-steaming ship at a rendezvous that might become compromised suddenly. There was the further inconvenience, and even danger, of having to take in supplies without adequate protection from heavy swell.

During August 13 Dresden and Baden were lashed alongside each other under the lee of Rocas Reef: but the Atlantic movement is no respecter of ships or nationalities. The two steel ships rose and fell, rolled inwards and outwards, crashing and banging severely in spite of all the fenders. Hawsers were snapped, and some actual ship damage inevitably occurred. Nor can we ignore these as negligible items. The psychological effect on officers and crew of having overwrought nerves still further strained by this monstrous jarring every few days was bound to be cumulative. Coaling ship is at all times an unpleasant evolution, and when it has to be done hurriedly under a tropical sky, with look-outs posted to report any possible enemy cruiser, and the ocean surge every moment endangering the men at work amid black dust and the din of donkey-engines, the operation each time intensifies the men’s annoyance with life.

Dresden did manage, however, to take in 254 tons, but the lighthouse-keeper at the island wanted to know who she was. The German fobbed him off with the lie that this was the Swedish ship Fylgia doing some repairs to defective engines. She sent Corrientes into Pernambuco, and presently there came two more supply ships, Prussia and Persia. We thus see that so efficiently planned was the German organisation that, notwithstanding the sudden incidence of war, there were at hand and with full cargoes, colliers perfectly placed to render necessary service. At the opening of hostilities there were 54 German and Austrian vessels in American Atlantic ports, New York alone containing nine large German liners such as the Vaterland, George Washington, Friedrich der Grosse, Grosse Kurfurst, and Kaiser Wilhelm II. On August 21 the North German Lloyd liner Brandenburg, with 9000 tons of coal and having taken in a large quantity of provisions two days previously, was permitted by the United States authorities to leave Philadelphia, under the declaration that she was bound for Bergen. Actually this Brandenburg, whose speed was only 12½ knots, was despatched by the New York German Supply Centre to a rendezvous near Newfoundland, and her presence would have been appreciated by any unit raiding the New York to England route. But Brandenburg never met a ship, held on across the Atlantic, reached Trondhjem on the last day of August and was interned by the Norwegian authorities, as we have already seen.

From Rocas Reef Dresden went south, and resumed her search for victims, being accompanied by Baden and Prussia. She got well across the north-east trade route and on August 15 captured the British S.S. Hyades, 3352 tons, Pernambuco for Las Palmas. The latter carried a cargo of grain, and was consequently sunk after the officers and crew had been taken aboard Prussia, the position of this first prize being some 180 miles to the north-east of Pernambuco. On the next day Dresden molested but released the British S.S. Siamese Prince, 4847 tons, and presently parted company with Prussia who steamed into port and landed her prisoners, but not at Pernambuco, Bahia, or any other adjacent harbour. That would never have done; not enough days would have elapsed. Prussia therefore entered Rio Janeiro, and in the meantime Dresden, after steering a false course so as to prevent the Hyades officers from providing accurate intelligence, went off towards the land-crab Island of Trinidada.

Here once more we note the Teutonic organisation and arrangements for concentration working out with extraordinary success. The only German warship in South African waters, just immediately before the war, was the little gunboat Eber. She was eleven years old, carried only two 4 1-inch guns, her displacement being 977 tons, and her speed 13 ½ knots. She was of negligible fighting value and likely to be sunk by any of the British cruisers of the Cape station. Eber wisely left Capetown on July 30, whilst the going was good, and went across the South Atlantic. Thither likewise proceeded the German S.S. Steiermark from Luderitz Bay (German South-West Africa). Now, during the night of August 18-19 Dresden was in wireless touch with Steiermark, and on arrival at Trinidada with Baden there was the assemblage of several supply ships which provided coal, stores and food. For, additional to Dresden, Eber, Baden and Steiermark, there had come the Santa Isabel which sailed from Buenos Aires on August 9, pretending she was bound for Togoland. Actually she brought out forty bullocks, oil, besides shovels and coal-bags, and a week later was met by another German steamer Sevilla which transferred to her both a wireless set and operator. It may be said at once that the useless Eber was about to hand over her guns to a crack German liner and enable the latter to go raiding. But this must be read in another chapter, since it led up to a most interesting series of events.

Dresden was now replenished with food and fuel, so that after two days she was able to go south-west and reach the trade route coming up from the River Plate. Thus she met the British S.S. Holmwood, 4223 tons on the 26th, when about 170 miles S ½ W of Cape Santa Marta Grande. The steamer was bound from Newport with Welsh coal for Bahia Blanca, and, after her crew had been placed aboard Baden, she was sunk by bombs. Already, then, the Dresden had reached as far south as the southern boundary of Brazil. But at this hour steamed up the British S.S. Katharine Park, 4854 tons, bound from Buenos Aires for New York with cargo for United States owners. She was therefore not sunk, but to her were transferred Holmwood’s crew, and she was dismissed on the understanding that officers as well as crew were not to engage in hostilities against Germany. On August 30 the Katharine Park reached Rio Janeiro, though by this time Dresden had carried on still further south till on the last day of August she reached Gill Bay (Gulf of St. George), which is some 800 miles from the River Plate.

She was under way again on September 2 and ready to resume her attacks, though the number of likely victims must necessarily be restricted to only those ships using the Magellan Straits or doubling the Horn. Captain Lüdecke was getting into cold latitudes, so sent on Santa Isabel in order to procure warm clothing, as well as materials for repairing his engines that had not been allowed their intended refit. This supply ship entered Magellan Straits and reached Punta Arenas on September 4, whence she was able to telegraph the Supply Centres of Buenos Aires and Valparaiso. She also sent a cable through to the German Admiralty at Berlin, and three days later came a reply ordering Dresden to operate with the cruiser Leipzig which was then at Guaymas (Gulf of California).

From now begins the second phase of Dresden’s voyage in which she was to pass from the Atlantic to the Pacific. The former was becoming not too healthy now that British cruisers were steaming up and down sweeping the Brazilian coast; though in truth a raider with adequate fuel could play hide-and-seek in the wide Atlantic for months, unless she were remarkably unlucky. After Gill Bay, Dresden chose not to enter Magellan Straits: she had kept her whereabouts shrouded in mystery and used her supply ship as a link between self and civilisation, thus giving a further instance of the reliance which the German Navy had placed on their auxiliary mercantile craft.

The beginning of September saw this cruiser butting into the wild seas off Cape Horn and encountering the chilly, depressing weather, grey skies, biting blasts, of a most inhospitable area. Making a wide sweep, she put into Orange Bay, Hoste Island, whence the turbulent ocean stretches direct to the frozen Antarctic. So rarely do vessels of any sort whatsoever use this forlorn anchorage, that it has long been a custom amongst mariners to “leave their card” by writing on a board the name of their ship with date. So when liberty men from Dresden were at last allowed ashore to stretch their legs after being at sea for several weeks, they discovered ship names and wrote on a board the word Dresden with the date, September 11, 1914. It was a natural, unthinking, but imprudent action; and the record was partially yet not entirely obliterated. There remained sufficient evidence, however, for her visit to be proved later on beyond all doubt.