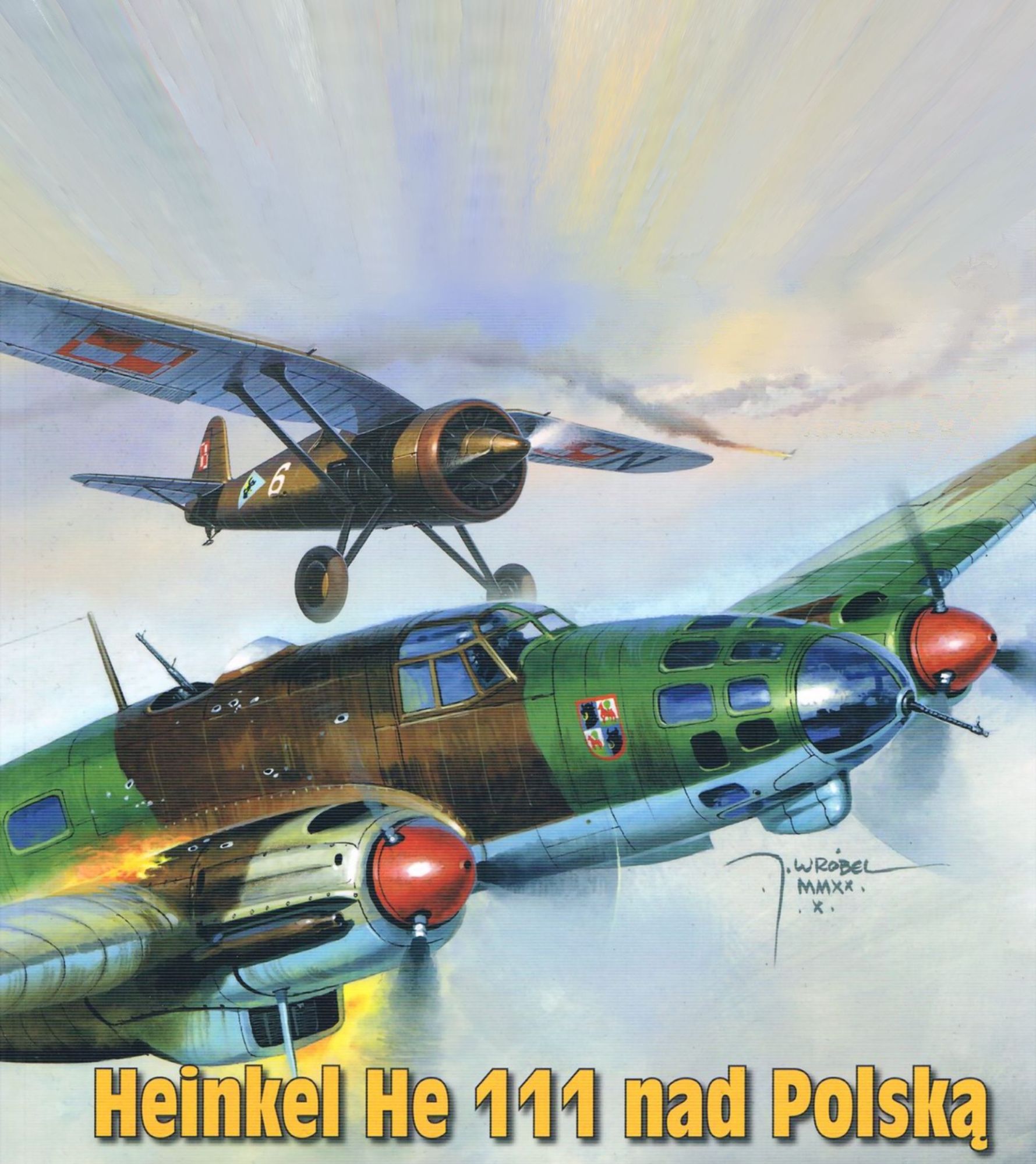

I./KG 1 ‘Hindenburg’ was the only Kampfgruppe still equipped with He 111Es upon the outbreak of hostilities on 1 September 1939

In the early hours of 1 September 1939 – the first morning of the world’s first Blitzkrieg – two-thirds of the Luftwaffe’s entire He 111 bomber force was being readied for a coordinated strike against Poland’s main military and naval airbases.

Seven of the twelve He 111 Kampfgruppen scheduled to take part in the operation were subordinated to Luftflotten 1 and 4, the two air fleets based in the eastern half of Germany facing the border with Poland. Two more were stationed in East Prussia, the province cut off from the rest of the Reich by the intervening ‘Polish Corridor’. The final three, forming part of Luftflotte 2, were stationed in northwest Germany. After completing their first mission, however, this latter trio were to land back on airfields around Berlin for temporary attachment to Luftflotte 1.

Such was the plan, but it was thrown into disarray by the weather. Dawn broke to reveal almost the entire region blanketed in low cloud and fog. Paradoxically, the only Gruppe to take off at 0430 hrs as briefed was the sole unit still equipped with the He 11 IE, Kolberg-based I./KG 1 ‘Hindenburg’. Its objective was the Polish Naval Air Arm’s seaplane base at Puck (Putzig), on the Baltic coast at the northern end of the infamous ‘Corridor’. A war correspondent flying in one of the bombers recorded his impressions of this first He 111 mission of World War 2:

‘Today, Friday, shortly after dawn, the Staffeln took off and headed eastwards. The rays of the rising sun reflected warmly on the camouflaged wings of the bombers. But it wasn’t long before the sun disappeared again behind a dense wall of fog that towered up into the sky ahead of us. It was only after a lengthy period of bad-weather flying, which demanded the utmost concentration from all the crews, that our formation reached the Polish land and naval air station at Putzig. There, Mother Nature was kind to us. The weather cleared just as we arrived over the target area, and even from our great height every detail could be made out.

‘I am sitting alongside the pilot on the folding seat that has just been vacated by the navigator/bomb aimer. He has clambered forward into the front of the nose and is now preparing for the bomb run. A moment ago I thought I heard a series of muffled thuds above the noise of the engines. Are the Poles actually shooting at us? While I am still pondering the matter, the pilot nudges me and points a finger upwards. He’s heard the explosions too. I feel a sense of satisfaction at being under fire for what would a combat mission be without some kind of response from the enemy!

‘Suddenly the aircraft gives a lurch. The bombs have left their magazines. I crane my neck to peer through the cockpit window and can see them tumbling down behind us, looking for all the world like beer bottles being thrown into a river from a high bridge.

‘The pilot pokes me in the ribs again and indicates the altimeter. We are flying at an altitude of 5000 metres and he’s leading our two wingmen into a gentle left-hand turn that will enable us all to see the results of our bombing. And, hurrah! It’s bang on target. The flickering flashes of bomb blasts straddle the seaplane base and surrounding areas. A few of our bombs have gone into the harbour, sending up huge fountains of water. Others have hit several large hangars. Columns of smoke rise into the air, grow bigger and start to spread. The attack has been a success.’

The primary target for I./KG l’s sister Gruppe, I./KG 152, was the Polish airfield at Torun (Thorn). But the slight sea breeze that had kept the fog at bay and had enabled I./KG 1 to take off from coastal Kolberg as planned did not penetrate the 30 km inland to I./KG 152’s base at Pinnow, near Reselkow. There, it was 0900 hrs before the ground mist cleared sufficiently to permit the He 111 Hs to lift off. They too were met by sporadic flak, but all aircraft returned to Pinnow without loss.

Further south still, Luftflotte 1 ‘s two other Gruppen – also scheduled to attack the Thorn airfields – had to wait even longer. On their forward landing ground at Schonfeld-Crossinsee the crews of I./KG 53 had been at readiness since 0230 hrs. But it was nearly midday before they took off to rendezvous with the Heinkels of II./KG 26 from nearby Gabbert. Both Gruppen then flew a second mission later that same afternoon, I./KG 53 going back to Thorn, this time to target flak emplacements and fuel depots, while II./KG 26 hit railway yards at Poznan (Posen). These two units also completed the day without loss, as too did the three Gruppen of KG 27 from Luftflotte 2, which carried out a massed raid on Warsaw by all 90+ of their available He 111Ps prior to coming under the temporary control of Luftflotte 1 for the remainder of the campaign.

In East Prussia one of the two He 111-equipped Gruppen of LG 1 was not so fortunate. II. and III./LG l’s main objectives for the day were airfields in the Warsaw area. The specific target for the nine machines of 5./LG 1 was an airfield near Modlin, but en route the Staffel reported coming under attack from ’25 Polish fighters’. Four bombers were damaged and a fifth shot down. Having lifted off from Powunden with the rest of II. Gruppe at about 0730 hrs, the luckless ‘Ll+KN’ may thus have the dubious distinction of being the first He 111 to be lost to enemy action in World War 2, for the only other known Heinkel casualty of 1 September was a machine of KG 4, whose three Gruppen were not cleared for take-off until very nearly 1300 hrs.

As the sole He 111 bomber presence under Luftflotte 4 in the far south, KG 4’s main effort was directed against the Cracow airfields. These were subjected to the combined weight of I. and III. Gruppen,, while II./KG 4 despatched a Staffel each to the airfields at Lwow (Lemberg), Lublin and Deblin. Although 5./KG 4’s raid on Deblin was reported as being ‘particularly successful’, it was from this mission that a machine had failed to return.

Marred only by the weather, the Heinkel’s operational debut in Poland was adjudged highly satisfactory. The second day of the campaign was a repeat of the first, with KG 4 attacking Deblin and the northern Kampfgruppen concentrating on targets in the ‘Polish Corridor’, Posen and Warsaw. Losses were again minimal, although three Polish fighters claimed a Heinkel apiece near Posen. But a disturbing number of reports were emerging of He 111s coming under fire from their own flak.

On 3 September, despite the declarations of war on Germany by Great Britain and France, the Heinkel force ranged against Poland was further reinforced by two more Gruppen of He 111Ps from Luftflotte 2. Departing their bases in northwest Germany, I. and II./KG 55 flew to airfields near Breslau to operate alongside KG 4 as part of Luftflotte 4.

By this time the initial strikes against Polish air bases were being scaled down. The Luftwaffe believed that it had already achieved its aim of neutralising the enemy’s air force. Although substantial damage had been inflicted, many of the Polish aircraft destroyed on the ground by bombing had been trainers and other secondary machines, some deliberately left out on display as decoys. The bulk of the Polish Air Force’s first-line PZL fighters had in fact been deployed to small satellite landing grounds just before the German invasion.

With the bombers now giving greater priority to the enemy’s communications and lines of supply, KG 55’s first mission – flown on the morning of 4 September – was directed against rail traffic in Kielce and Cracow. It was on this date too that Polish resistance on the ground, which had been strong up until now, began to show signs of weakening. The opening phase in the defence of Poland, the so-called ‘Frontier Battle’, was drawing to a close and Polish forces were falling back with the intention of forming a new line along the Vistula and San rivers.

It was a similar situation in the far north. There, the detested ‘Corridor’ – the cause of so much friction, both manufactured and otherwise, between Germany and Poland – was on the point of being eliminated. This would leave the invading Germans free to wheel southwards and advance on Warsaw. Another war correspondent provided an account of a raid on Bydgoszcz, a town at the base of the corridor, shortly before its fall on 5 September:

’15 minutes to go before take-off, which is scheduled for 1000 hrs. The usual early morning mist has lifted, and the bombers are bathed in sunlight. They are dispersed about the field, separated into Ketten and Staffeln, and groundcrews are carrying out last-minute checks. Small groups of NCOs are making their way across the broad expanse of open grass towards their aircraft, where they are joined by their officers returning from Staffel briefings.

‘We – that is the pilot, navigator/bomb aimer, wireless operator/upper gunner, flight engineer/ventral gunner, plus my good self as supernumerary camera operator/gunner – climb into our crate “C-Cäsar through the “bathtub”, the gondola on the underside of the fuselage. The crew take their places, the upper gunner wriggling into his revolving cradle seat and traversing his machine gun. Our leutnant, who acts as both navigator and bomb aimer, is already studying his maps.

‘Everything is in order. On the dot of 1000 hrs the chocks are pulled away from the wheels, 2400 horses begin to bellow as the pilot guns the engines and we start to roll. I catch a glimpse of the runway marshal waving his green and white flag and moments later we are in the air. To our left the other machines of the Staffel appear above the tiny wood bordering the field and close up on us. One last circuit. The small white dot tearing about on the grass below is the Staffel mascot, a cheeky little terrier who answers to the name of “Flox”. He’s obviously none too pleased that his many masters have deserted him and are making such an infernal din as they climb away into the sky.

‘We quickly gain height. At the head of the formation the Staffelführer’s machine sets course eastwards. The aircraft alongside us has already retracted its wheels. From the movements of its machine guns, I can tell that the gunners over there are also at their posts and already scanning the sky.

‘We break through a thin but dense layer of cloud. Above us a clear sky the colour of steel. Below us an enormous ocean of white cotton wool, its smooth surface broken here and there by towering cloud formations. We have already crossed the Reich’s border, but as yet there has been no sign of the enemy. I leave the cockpit and clamber down through the small fuselage hatch into the “bathtub”. The ventral gunner grins at me and gives me a hefty punch on the shoulder. The bruise that develops will be the only wound I have to show for flying this particular mission.

‘The cloud is beginning to break up a little. Now and again a village, a patch of woodland or a small lake can be seen, only to disappear again just as quickly. The Staffel continues on its way undisturbed. Nine grey-green specks suddenly pop up behind us out of nowhere. They rapidly overtake us and turn out to be German fighters, Messerschmitt 109s. As they cross our path they waggle their wings in greeting. We return the compliment, but in a slower and more sedate manner as befits a bomber.

‘It can’t be long now. Up in front the pilot and navigator have got their eyes glued to the Staffelkapitan’s machine. The clouds have thinned out even more now to reveal several larger towns. There! The leading aircraft is opening its bomb-bay doors. Our leutnant lies ready and waiting, peering intently into his bombsight. Now!

‘Large grey shapes tumble from the machine ahead. We immediately release our own bombs. Soon the first bombs can be seen exploding among buildings on the banks of a river. Now all the other aircraft are dropping their bombs, followed by glittering silver shoals of incendiaries.

‘By this time the Polish flak has opened up, but the enemy’s fire is confused and inaccurate. The whole affair has lasted little more than two minutes. We have reversed course, the clouds have closed in again beneath us and we are all safely on our way back to base.’

Between 4 and 6 September I./KG 1 and I./KG 152 moved up from their bases in Pomerania to forward landing grounds closer to the Polish border. The transfer resulted in each unit suffering its first casualty of the campaign. The loss of I./KG 152’s ‘V4+A13’ on 5 September has been variously attributed both to Warsaw’s flak defences and to PZL fighters. The former is perhaps marginally the more likely, as Polish fighter pilots initially described their victim as a Bf 110.

A more disturbing case of faulty aircraft recognition occurred the following day when a machine of I./KG 1 was shot down near Lodz with the loss of its crew. One source identified the culprit as a Bf 109D fighter of I./ZG 2 (although, understandably perhaps, there is no record of any Messerschmitt pilot submitting a claim for an He 111 on the date in question!). Such incidents were not uncommon in Poland, Heinkel crews frequently reporting instances of ‘friendly fire’, both from the ground and in the air. Fortunately, few proved fatal. But the situation was considered serious enough for many He 111 units to have grossly oversized crosses painted on the upper and lower wings of their aircraft.

I./KG 4 was also in action not far from Lodz on 6 September, losing three of their number – one to flak and the other pair to PZL fighters- while attacking bridges over the Vistula south of Warsaw.

With the campaign in Poland nearing the end of its first week, it was apparent that the demarcation line between Luftflotten 1 and 4’s areas of operations was becoming much less rigidly defined. The ground fighting in the north of the country was all but over and the Luftwaffe’s Kampfgruppen were beginning to direct their focus of attention to the south. Their main purpose now was to harry the retreating Polish army, stopping it from establishing a new defensive line along the Vistula and preventing any attempts to escape southeastwards into Rumania.

7 September thus witnessed not only LG 1 ‘s two East Prussian-based Gruppen targeting the railway network in central Poland, it also saw four of Luftflotte l’s He 111 units ordered to the southern sector. I./KG 1 and I./KG 152 left the Baltic coast area and transferred down to BreslauSchongarten, while II./KG 26 and I./KG 53 took up temporary residence at Nieder-Ellguth and Neudorf, also in Silesia. From here they were to fly low-level missions in direct support of the German army in the field.

This was a complete departure for the He 111s, whose primary role hitherto had been high-altitude bombing raids on fixed objectives. And these new missions were to expose another weakness in the basic Heinkel design. Although it had been the best of the trio of pre-war bombers tested by the Luftwaffe in terms of speed and bomb-carrying capacity, these attributes had been bought at the expense of arms and armour.

The first week of combat in Poland had already revealed that the Heinkel’s relatively weak defensive armament made it vulnerable to determined fighter attack (something already hinted at in Spain). Now, low-level operations – usually carried out either singly or in Ketten of three aircraft – were to highlight the He Ill’s deficiency in armour and its susceptibility to an unlucky hit from light Flak or ground fire. By 8 September spearheads of the German army had reached the outskirts of Warsaw. The final outcome of the campaign could no longer be in any doubt, but the fighting was far from over and the Heinkel Kampfgruppen continued to suffer casualties. On 9 September I./KG 1 lost two of its He 111 E s to a combination of fighters and flak over Lublin. A machine of LG 1 was also lost on the same date, being forced to land behind enemy lines near Deblin.

Two newcomers to the Polish front had flown into East Prussia on 8 September. Temporarily detached from their parent Gruppen in northwest Germany, 2./KG 54 and 5./KG 28 undertook their first missions 48 hours later. All aircraft returned safely from a high-altitude raid on Polish troop concentrations near Warsaw on the morning of 10 September. But a low-level attack by the two Staffeln on enemy columns in the same area later that afternoon was met by heavy ground fire that brought down one of 2./KG 54’s He 111Ps.

The Polish army launched an ambitious counter-offensive along the River Bzura to the west of Warsaw on 11 September, but it was quickly and effectively brought to a halt, not least by the Luftwaffe’s ground-support units backed up by the Heinkels of KGs 1, 4 and 26. Elsewhere, the other He 111 Kampfgruppen continued to strike at retreating enemy troop columns. Attacked by PZL fighters over Przemysl in the far south on 11 September, a He 111P of KG 55 had been forced down between the opposing lines. All those aboard were rescued from no-man’s land by German troops.

The crew of a Geschwaderstab LG 1 Heinkel was not so fortunate. ‘Ll+CA’, which took a direct flak hit over Warsaw on 11 September, was to be the fifth and final He 111H lost by the Lehrgeschwader during the campaign, for the Luftwaffe High Command had already issued orders for the gradual withdrawal of the Heinkel Kampfgruppen from the fighting in Poland. And among the first to retire were II. and III./LG 1. They departed on 12 September together with II./KG 26 and I./KG 53.

The following day most of the remaining units participated in Operation Wasserkante (Northern seaboard), the last mass raid on Warsaw. It was carried out by a force of some 180 bombers, and laid waste to further large areas of the Polish capital. Then, on 14 September, bad weather closed in. Flying activity was reduced to a minimum for much of the next week. At least one more Heinkel raid was flown against Warsaw, however, as witness the following account:

‘Not to put too fine a point on it, the weather conditions were – to use an old flyers’ expression – “an absolute pig”. Every half-hour a slight break in the overcast. Every hour perhaps a brief glimpse of the sun. For the rest of the time an absolute “pea souper”, hovering above the field at anything from 200 to 600 metres. But the “weather frogs” – the meteorologists – knew better. According to them an area of good weather was approaching from the southeast. Take-off was therefore scheduled for 1310 hrs.

‘And so it turned out. On the dot of 1310 hrs the first Staffeln of our two Gruppen roared off. Our crew had drawn the short straw. We were assigned to bring up the rear of the whole formation and not only “lay our own eggs”, but also take aerial photographs to establish the results of our two Gruppen s bombing. To revert back to flying jargon, we were to be the “Aunt Sally” in the event of any attack from astern.

‘At least, we thought, we won’t have to worry too much about navigation. Just follow the bunch in front of us. But no such luck! By the time we had climbed to 400 metres every single machine ahead of us had been swallowed up in the murk. We were thus very much on our own as we too plunged into the milky-grey blanket of fog.

‘Our course was to take us to Praga, the eastern suburb of Warsaw, where, according to reports, the Poles were still holding out. At 2800 metres we finally emerged from the clouds. As we crossed into Poland we found ourselves flying above a fantastic white carpet. Bathed in bright sunlight, the tops of the clouds, like tightly packed balls of cotton wool, stretched unbroken in every direction.

‘Our navigator was beginning to look thoughtful. We had to be spot on target – not only to drop our own bombs, but also to make our photographic run. On top of that we had orders that, under no circumstances, were we to inflict any damage on the Polish capital’s diplomatic quarter, which was separated from our objectives by nothing more than the width of the River Vistula.

‘But we were in luck. Gaps began to appear in the clouds. And through one of them we could see in the far distance diagonally ahead of us the silver ribbon of the Vistula. It was unmistakeable, the river’s many sandbanks turning it into a filigree of individual channels all sparkling in the sunlight.

‘From our height of 4000 metres we dived quickly through the opening in the clouds and there spread out in front of us lay Warsaw. A brief glance took in the city’s four bridges – ideal marker points, as the railway stations we were after were situated on the right bank of the river level with them. Below us we saw the last Kette of our Gruppe just leaving the target area and retiring northwards, pursued by heavy and fairly accurate flak.

‘Once again fortune smiled on us. Despite the smoke hanging in the air we were able to line up our sights on the eastern railway station almost undisturbed. And by the time we came round again to take our photographs the enemy fire had died away completely. Mission accomplished!’

The bad weather of 15 September did not prevent I./KG l’s transfer from Breslau to Krosno, in southern Poland, on that date. The Gruppe’s He 111Es may thus have become the only Heinkel bombers to operate from Polish soil, although they carried out relatively very few missions during the 48 hours they were there. 15 September also saw KG 55’s only total loss of the campaign when a 1. Staffel crew failed to return from a raid on Dubno.

Poland’s fate was finally sealed by the Red Army’s invasion from the east on 17 September. By that time the He 111s’ part in the campaign was effectively over. On 18 September, while still pinned down at Breslau by the adverse weather, I./KG 152 was officially redesignated to become II./KG 1. The following day both I. and II./KG 1 returned to their home bases, as too did I./KG 4.

Since their Dubno mission of 15 September both Gruppen of KG 55 had also remained grounded by the atrocious conditions. The rain had poured down, turning their fields into ‘little more than mudholes’. But on 20 September the weather improved sufficiently to allow them to start withdrawing. 2./KG 54 and 5./KG 28 also returned to their parent Gruppen on 20 and 21 September respectively. The last He 111 Kampfgruppen of all to retire from the Polish campaign were II. and III./KG 4, which finally departed on 22 September.

The defenders of Warsaw were to hold out for five more days, and they suffered bombardment until the very end. However, with the Heinkels all back on their home fields, the final raids on the beleaguered Polish capital had to be carried out by Ju 52/3m transports, their crews reportedly ‘shovelling incendiaries out of their side loading hatches’.

Love the images, what are the sources?