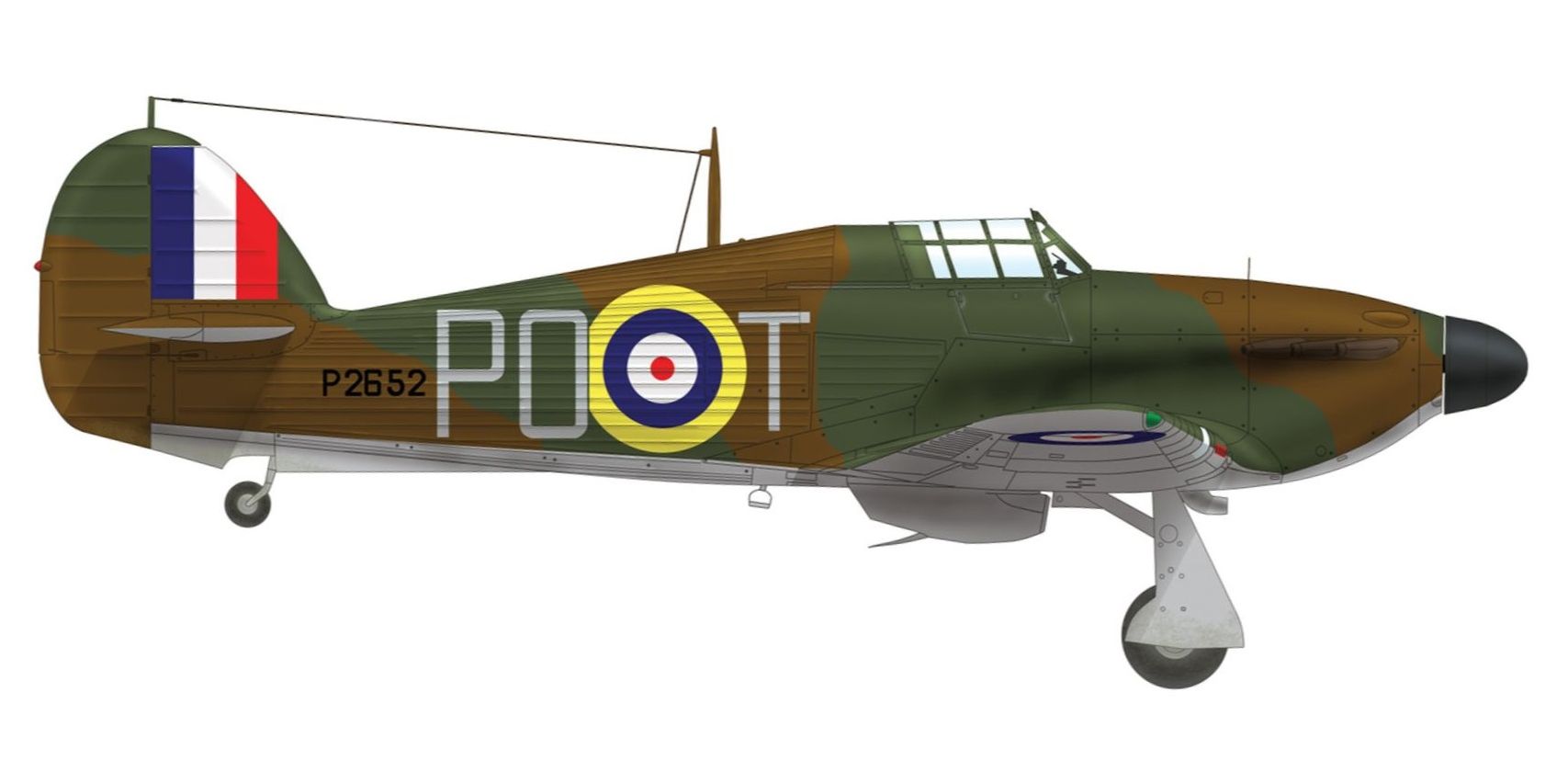

Hurricane Mk I of 46 Squadron during the Norwegian Campaign, May 1940. This aircraft was abandoned in Norway

Stavanger/Sola, 450 miles from our bomber bases on the east coast, was raided for the first time of 11/12th April, and more heavily on 14th April. Thereafter it was bombed regularly; for by 14th April British forces were landing on Norwegian soil, and the bombing of Stavanger was one of the few available means of reducing the weight of German air attack against them.

The key to recovery in Norway was of course Trondheim. If we could recapture this large and flourishing port, with Vaernes airfield no great distance away, the northern half of Norway could almost certainly be held—for near Trondheim the country narrow sharply, and the distance across to Sweden is only sixty miles. Forces could then be built up for a subsequent advance to the south. With this in mind, and with the knowledge that the German troops in possession numbered as yet no more than two thousand, the Norwegians therefore urged the Allies to undertake an immediate and direct assault. But an operation of this kind could not be carried out without heavy losses among our ships, and though the plan was adopted in principle it was not applied. Instead a beginning was made with a subsidiary movement—an overland advance on Trondheim from two directions. One wing of this was to land at the small harbour of Namsos, 125 north of Trondheim, the other at the equally small harbour of Aandalsnes, 200 miles by road to the south.

Meanwhile, a third and entirely independent force was to recapture the remote and isolated port of Narvik.

The first naval party put ashore at Namsos on 14th April. The same day British forces began to land near Harstad in Vaags Fjord, the base selected for operations against Narvik; and on 17th April an advanced party disembarked at Aandalsnes. All these landings were unopposed, and since some initial progress was quickly made from Namsos and Aandalsnes the plan of a direct assault on Trondheim up the fjords was abandoned with relief, and all efforts were concentrated on the advance over land.

The troops at Namsos were under the command of Major General Carton de Wiart, V.C., a soldier whose gallantry from the day of the Boer War onwards had become almost a legend. De Wiart, who arrived by Sunderland flying-boat on 15th April to the accompaniment of German bombs, lost no time in pushing forces south through the vital defile of Steinkjer. A halt then ensued while further troops—a French demi-brigade—were brought into Namsos on 19th April. But the Frenchmen were no sooner landed and the ships withdrawn than the Luftwaffe, whose activities over this area had thus far been sporadic, appeared on the scene in strength. In the absence of anti-aircraft defences their task was not difficult, and by nightfall on 20th April Namsos was virtually destroyed. ‘The whole place’, wrote a naval eyewitness, ‘was a mass of flames from end to end, and the glare on the snows of the surrounding mountains produced an unforgettable spectacle’. The railway station, the rolling stock and the storehouses on the jetties all suffered in the general devastation, and the road transport disappeared with the evacuating Norwegian population.

The lesson of this was not lost on de Wiart. The following morning he signalled the War Office ‘I see little chance of carrying out decisive, or indeed, any operations, unless enemy air activity is considerably restricted’. Two days later, after German forces shipped along the fjords from Trondheim had landed on the flank of his advanced troops, and after the Luftwaffe had twice subjected the forward units and the town of Steinkjer to the same treatment as the base at Namsos, de Wiart put it more strongly—that there was ‘no alternative to evacuation’ unless he could have superiority in the air. From this point onwards the General could act only on the defensive, and his best hope, that when the order to withdraw was given, was that he would succeed in getting his forces back on Namsos. The advance on Trondheim from the north had failed.

Meanwhile, the other jaw of the would-be pincers was trying in vain to operate from Aandalsnes. The first formation to land consisted of some sixteen hundred men, containing a very high proportion of raw troops and a very low proportion of transport and guns. Before advancing north the brigade was ordered to secure the vital junction of Dombaas, where the railway from Oslo divides for Aandalsnes and Trondheim. The bulk of the Norwegian army was at this time well south of the junction, fighting a stout delaying action against the main German drive from Oslo; and if this advance could be halted before it reached Dombaas our own movement towards Trondheim could be conducted without interference. But the hard-pressed Norwegians were naturally reluctant to see our troops merely consolidating a position in their rear, and it was to meet their requests that Brigadier Morgan pushed his men well down the valley past Dombaas to the advanced positions around Lillehammer. Before our men were properly established in the line, however, the forward Norwegian troops had been driven back. At the limit of endurance they succumbed to the combined assault of German land and forces; for the pilots of the Luftwaffe, taking advantage of a settled spell of fine weather most unusual in Norway at this time of the year, were flying up and down the snow-bound valleys at will, selecting their targets with the greatest deliberation. The full shock therefore fell on Morgan’s brigade, who at first fared little or no better than the Norwegians. While they strove to restore the situation, a second brigade which had been landed at Aandalsnes was rushed down to give them support. The Aandalsnes expedition, so far from driving north against Trondheim, was thus desperately engaged in trying to hold off the Germans to the south.

While our troops were struggling to establish themselves in central Norway the Royal Air Force had not been idle. It had repeatedly bombed Stavanger/Sola airfield; it had attempted the more difficult tasks of bombing the two vital airfields at extreme range—Trondheim/Vaernes and Oslo/Fornebu; and it had made its first attacks on the Danish airfield at Aalborg, of which the enemy was making great use. It had not, however, attacked airfields in German, of which the enemy was making even greater use—for the policy of not provoking German air action against this country was still maintained. Nearly two hundred sorties were flown against the airfields in Norway and Denmark between 14th and 21st April; but the distance was considerable, the weather over the North Sea often unfavourable, and the enemy defences too strong to allow our aircraft to operate except by night or under cover of cloud. The net effect on German air activity over Norway was therefore small.

The Royal Air Force had also joined battle against the enemy’s sea communications. Beginning on the night of 13/14th April our aircraft had laid magnetic mines in the Great and Little Belts, the Sound, the Kiel Canal, the Elbe estuary, and many other areas which our ships could not approach. Though undoubtedly less dangerous than operating over Germany, this was by no means easy work. The flights were long, and might the aircraft to such hotly defend places as the Kiel Canal or Oslo Fjord; the mines, weighing fifteen hundred pounds each and attached to a parachute, had to be dropped from only five hundred feet or so above the water; and in thick weather there was every likelihood of having to turn back and land with the mines still on. By the end of April Bomber Command’s Hampdens had sown 110 mines at a cost of seven aircraft, which others had been laid by Coastal Command, the Fleet Air Arm and the submarines. All this was to prove very profitable in the long run, but it was certainly not decisive for the campaign in Norway. In fact, the enemy took across everything he wanted. Between mid-April and mid-June the Germans lost on the Norwegian route only eight or nine percent of their shipping and only 1,000 of the 100,000 officers and men transported.

The mining and the attacks on airfields had their value, but it was not apparent to troops who were spending their time dodging German bombs. Our men in Norway, ludicrously short of anti-aircraft guns, were also desperately in need of fighter protection. The problem was easier stated than solved. No Royal Air Force units had been detailed for central Norway; all known airfields had been seized by the enemy; and emergency landing grounds could hardly be constructed with any great speed in mountainous country several feet under snow. To achieve what was possible in the circumstances, the aircraft carriers Glorious and Ark Royal were recalled from the Mediterranean and despatched on 23rd April to give support off Namsos and Aandalsnes; and on board the Glorious went one fighter squadron of the Royal Air Force. It was No. 263, from Filton; it was chosen because its obsolescent Gladiator biplanes could operate from small landing grounds.

The selection of an operation site for the Gladiators had been no easy task. In that wild and mountainous country, where a forced landing is an impossibility and the parachute is the pilot’s sole hope in emergency, only a frozen lake offered any chance of a flat surface. At Lake Vangsmjösa, where there was very little snow, some remnants of the Norwegian Air Force were operating off skis. To Squadron Leader Whitney Straight, who had been sent to explore the district, the best solution the best solution seemed for the Gladiators to join the Norwegians there; but the Chiefs of Staff rejected the recommendation on the ground that the site was exposed to a German advance and could be supplied only a separate and dangerous route. Instead, they approved Straight’s second choice, Lake Lesjaskog, which lies in the valley connecting Aandalsnes and Dombaas, and was therefore along our existing lines—or line—of communication. This decision taken, Straight at once got down to business. Within two hours of his arrival at Lesjaskog he had 200 civilians—an almost incredible number in a place so sparsely populated—hard at work on the task of clearing a runway through the two feet of snow that covered the ice.2

Shortly before midnight on 22nd April a Royal Air Force advanced party under Wing Commander Keens arrived at Aandalsnes. Its function, until a full Royal Air Force Headquarters could be set up, was to establish a base at the port and servicing facilities at Lake Lesjaskog. The night was spent in clearing stores from the jetty, and the following morning some of the servicing facilities at Lake Lesjaskog. The night was spent in clear stores from the jetty, and the following morning some of the servicing party proceeded up the valley of the lake. There they arranged fuel dumps around the newly cleared runway and in the woods which go down to the water’s edge. Twenty-four hours later, at midnight on the 23rd, the servicing equipment arrived at Aandalsnes. It was rapidly unloaded, but only two lorries—impressed form the local population, for the British authorities had none—were available to transport it up to the valley to the lake. Only the most vital items could go forward; and this meant opening every box to examine its contents, since no schedule of equipment had been provided. But by midday on the 24th the equipment had been provided. But by midday on the 24th the essential gear and the remainder of the servicing flight had left for the lake, and during the afternoon Wing Commander Keens signalled the waiting carrier—by way of the Air Ministry—that the Gladiators could land at 1800 hours.

When the time came for Squadron Leader Donaldson, the Commanding Officer of No. 263 Squadron, to fly his aircraft off, the Glorious was 180 miles from the shore in the thick of a heavy snowstorm. Donaldson was a brave man, but he had little relish for the task that lay before him; for his squadron, with four maps between them and no more navigational facilities than those usually to be found in fighters, had to make their first take-off from the deck of a carrier, locate in poor visibility an unknown spot set among mountains, and land on ice. He asked the captain if a Fleet Air Arm Skua might lead the squadron to the lake. The request was readily granted; the eighteen Gladiators flew off without mishap and without mishap they landed on Lake Lesjaskog.

What they found at Lesjaskog might have dismayed less cheerful hearts. The valley being wide at this point, there was no difficulty about the approach, and the single road and railway from Aandalsnes ran close to the lake. But the prepared runway was some distance from the shore, for the ice at the edges was already beginning to melt; the only transport available to take stores from the road to the runway was an occasional horse-drawn sledge; the servicing party, designed and equipped simply to operate until the squadron ground staff arrived, had no petrol-bowser and only two refuelling troughs; the starter trolley batteries were uncharged and had no acid; and there was no warning system to report the approach of hostile aircraft. It was to conditions of this sort that the Gladiators arrived, in a district over which German aircraft swarmed at will; indeed, the preparations on the lake had already been systematically observed by the enemy. But, though their Commanding Officer had noted with apprehension the bomb damage along the railway, the pilots of No. 263 Squadron were far from downcast. They were young, they were amid the glittering beauty of the snow and the ice and the stars, they were comfortably housed in the little summer hotel nearby, they were at last on the threshold of action, they were superbly cheerful. They would have been still more cheerful that evening but for the bore of having to disperse their aircraft. Their outlook was that of the British solider in Aandalsnes who, seeing them fly over on their way to the lake, remarked to a local inhabitant, ‘Here come our fighters—no more German bombers now’.

The dawn brought swift disillusion. The Gladiators were put up a patrol over the Dombaas area at 0300 hours. But the sharp frost of the spring night had frozen the carburettors and the controls, and ice locked the wheels to the runway. Only after two hours’ struggle did the first pair of aircraft get off the lake and proceed to Dombaas, where their appearance over our lines put fresh heart into the troops. Meanwhile, the desperate efforts of the squadron to start up the rest of the Gladiators were surveyed by two German aircraft, which dropped a few ineffectual bombs. Two hours later the serious business began. In relays of threes, unescorted Ju.88’s and He.111’s returned again and again, while the engines of the Gladiators still defied attempts to wake them to life. At length some accumulators were commandeered from passing lorries, and under attack from bombs and machine-guns two more Gladiators managed to start up and take off. While they circled the lake others succeeded in joining them, and from then on the squadron was able to give a good account of itself. Starting up, however, was merely the first of its difficulties; for the part included only one armourer, and with the limited equipment available and the enemy constantly overhead, refuelling and re-arming was a painful, lengthy and dangerous process. Such conditions could have only one end. Despite the pilots’ best effort in the air and despite the heroic work of a small naval party manning two Oerlikon guns near the lake, by midday ten of the eighteen Gladiators had been put out of action on the ground.

It says everything for the pilots of the squadron that in conditions such as these they were able to make upwards of thirty sorties during the day, to fight many combats, and to shoot down several of the enemy. But one day was enough. Towards evening, when the runway as well as the squadron was virtually destroyed, the Squadron Commander flew down to Setnesmoen, near Aandalsnes, and landed on a small plateau which was being hastily cleared as an emergency landing ground. Finding it reasonably satisfactory, and well placed to reflect the base, if far removed from the front line, he ordered the four remaining Gladiators to join him. During the night the few available lorries brought down to the coast such fuel, stores and ammunition as remained; and when the morning sun rose on Lesjaskog, it revealed only a scene of smashed and splintered ice, broken trees and burnt-out aircraft.3

From Setnesmoen on 26th April the surviving Gladiators made their last effort. Between them the five carried out a useful reconnaissance and a patrol over the forward lines; then there were three. These three attempted to engage the German aircraft which attacked Aandalsnes at leisure throughout the day, but with no oxygen the pilots were completely unable to operate at the 20,000 feet from which the enemy, respecting their presence, chose to bomb. Finally, one Gladiator alone remained doubtfully serviceable; and for this there was no petrol. Nothing remained but to withdraw the pilots in a cargo vessel. Surviving several attacks from German bombers they reached Scapa Flow safely on 1st May—exactly ten days after they had sailed to Norway from the same place. Their adventure had been brief, and expensive in aircraft, but at least well rewarded in experience. For the story of No. 263 Squadron as Lesjaskog will forever stand witness to the futility of exposing a handful of machines, with hastily contrived and inadequate arrangements on the ground, to the full blast of operations by a powerful enemy.

The destruction of No. 263 Squadron meant that there was now little hope of keeping Aandalsnes in use; for the gallant and skilful work of the Fleet Air Arm pilots of the Glorious between 24th April and 27th April could not avail to save the base from the frightful effects of German air superiority. In the words of the naval officer in charge, ‘… the wooden quays destroyed, the area surrounding the single concrete quay devastated by fire, the roads pitted by bomb craters and disintegrated by the combined effect of heavy traffic and melting snow, the recurrent damage to the railway, the machine-gunning of road traffic—all made it patent to those on the spot that it was only a question of time for the port activities to diminish to such an extent that the line of communication could not be maintained.’ With the neighbouring port of Molde in no better case, our ships in harbour in constant danger, and Namsos—despite fine work by the aircraft of the Ark Royal—as badly hit as Aandalsnes, the end was indeed certain. Though everywhere hard-pressed and withdrawing, our troops in contact with enemy ground forces could have held on longer; it was the air bombardment of their bases which threatened disaster complete and irreparable. Recognizing this, Lieutenant-General Massy, the Commander-in-Chief of the Expeditionary Force—whose headquarters were still in London—regarded the destruction of No. 263 Squadron as decisive; almost as soon as he heard of it, on 27th April, he advised the Chiefs of Staff to abandon the entire Central Norwegian project. The following day the local commanders received the order to withdrawn their forces.

The function of the Royal Air Force during the evacuation was to reduce the enemy’s air activity by bombing his airfields, and to give what cover it could to the withdrawal from Aandalsnes. The second part of this task demanded what we so conspicuously lacked at the time—a good long-range fighter. The makeshift Blenheim fighter was all that we could boast in this category; and of these only one squadron was available for operations. The intention was that these aircraft should land and refuel at Setnesmoen, but before they could do so the Luftwaffe had put the landing ground out of action. All operations were accordingly carried out from this country, with the result that each sortie could spend no more than an hour near Aandalsnes. As for Namsos, this was quite beyond the range of any Royal Air Force fighters; but protection was to be given by the Ark Royal and the Glorious, which had returned home to refuel and were due back off Norway on 1st May.

In accordance with this plan Bomber Command attacked Stavanger/Sola and Oslo/Fornebu airfields by day and night throughout the entire period of the evacuation, besides directing a less number of sorties against the Danish airfields of Aalborg and Rye. The heaviest raid was on the night of 30th April/1st May, when twenty-eight Wellingtons and Whitleys bombed Stavanger at a cost of five aircraft. This effort, coming on top of those already undertaken, had its effect, for by 1st May the Germans were confining the use of the surface to emergency landings. During the critical days the weight of enemy air attack on Aandalsnes and Namsos was therefore materially less. All the same, there was plenty of activity against our ships at sea—so much, in fact, that when the two aircraft carriers duly reappeared off Norway on 1st May, and were promptly selected for special attention by the Luftwaffe, they were soon ordered home. this meant that our forces had to make good their escape from Namsos with no air cover whatsoever.

In spite of the scanty measure of protection that could be supplied by the Blenheims the evacuation from Aandalsnes went well. The enemy air force made no attempt to interfere with the embarkation during the hours of darkness, the final parties were cleared on the night of 1st/2nd May, and all vessels reached British ports safely. Up to this point the Germans, strangely enough, seem to have been unaware of our intentions; having captured the plan for building up our forces through Aandalsnes, they perhaps imagined that we were still coming, not going. But on 2nd May, before de Wiart’s men at Namsos had even begun to embark, Chamberlain announced in the House that we had withdrawn from Aandalsnes. The inference that we might also be withdrawing from Namsos was not difficult to make, and perhaps because of this the Luftwaffe was able to subject the Allied convoys to repeated assaults on their homeward passage. Two destroyers were sunk. Only when our ships came within the orbit of Coastal Command did the attacks.

#

While Central Norway was witnessing the first of those evacuation which were to feature so prominently in our military efforts during 1940 and 1941, the expedition in the North was in a fair way to success. For whereas Namsos and Aandalsnes were within easy reach of airfields held by the enemy, Narvik was not.

The port of Narvik is some 600 miles north of Oslo as the aeroplane flies, and 400 miles north of Trondheim. Within the Arctic circle and set amidst mountains wild to the last degree, it gives the impression of some desperate triumph of man over nature. The port remains open throughout the year, but between September and the beginning of May the country is entirely covered with snow and ice, and in mid-winter the only light of day consists of two hours of murk and gloom. Remote and inhospitable, Narvik has few communications with southern Norway: the single track railway runs directly east to the Swedish orefields, and the traveller who attempts the journey south by road—if road it may be called—faces the prospect of shipping his car across several fjords. Even the all-conquering aeroplane which bids fair to ‘put a girdle about the earth in forty minutes’, is at a disadvantage. A flight between North and South Norway is usually marked by swift and treacherous changes of weather which may spell death to the airman who ventures on; great down-draughts snatch at the aircraft as it tops the mountain peaks or noses its way through the defiles; and there are few places within fifty miles of Narvik where anything other than a float-plane or flying-boat could possibly alight. Of such landing grounds as there were in 1940, though one or two of them were normally occupied by small detachments of the Norwegian Air Force, none could be dignified with the name of airfield.

The British element of the Narvik expedition sailed on 12th April ,a few hours before Admiral Whitworth disposed of the German destroyers by his action in the fjords. The military commander was Major General Mackesy, who instructions were to establish a base at Harstad, a small fishing port on an island in Vaags Fjord, fifty-five miles by sea from Narvik. When the news of Whitworth’s victory reached the commander of the naval forces, Admiral of the Fleet the Earl of Cork and Orrery, he at once proposed that the Harstad project should be cancelled in favour of an immediate and direct assault on Narvik; but the suggestion made on appeal to Mackesy, whose brigade had embarked for an unopposed landing, had been neither trained nor equipped for movement over snow, and would have had to advance unsupported through snow waist deep in the face of enemy gunfire. Although the German forces at Narvik were small, our troops therefore landed, as originally intended, at Harstad. A plan was then made to capture the ground north and south of the peninsula on which Narvik stands so that the port itself might be taken from the rear. This involved waiting for reinforcements—and the thaw.