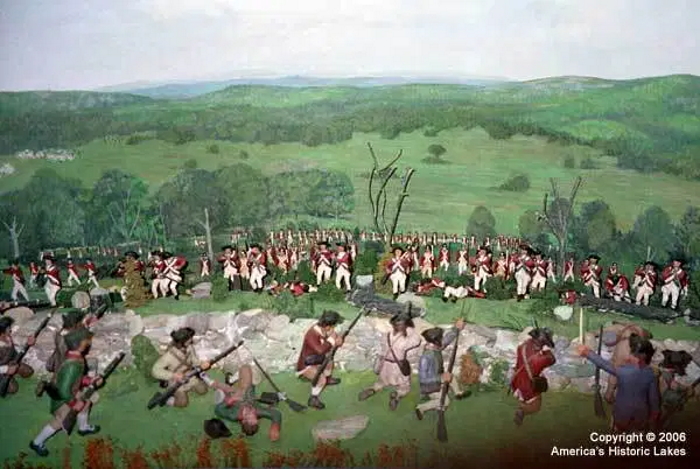

Model of Monument Hill and stone wall behind which Colonel Francis’ regiment poured shot down upon the British 24th and Light Infantry Battalion.

When he marched his dejected garrison out of Mount Independence in the early morning hours of Sunday, July 6, 1777, St. Clair intended to head toward Castleton, about 30 miles southeast of Ticonderoga, and then travel the 14 miles back east to Skenesborough. There they would rejoin Colonel Long with the supplies and sick that had been evacuated by water. The dejected Americans retreated along the primitive military road running out of Mount Independence. The route was dictated by the available roads that had not already been cut off by Burgoyne’s army. As the sun rose, the temperature quickly soared, and St. Clair’s exhausted and demoralized men suffered from the intense heat, humidity, and the ubiquitous insects, not to mention anxiety, knowing that the enemy was nipping at their heels.

The British pursuit came quicker than anyone expected. Fraser had immediately put elements of his advance corps on the road to chase the fleeing Americans. To support Fraser, Burgoyne ordered General Riedesel and his men to follow Fraser and support them in case of an attack. The fleet and the rest of the army were to make their way to Skenesborough by water and attack the Americans’ fleet. British warships were soon closing in on Colonel Long’s vessels, and British troops were already following St. Clair and the main body. General Riedesel quickly gathered up his forces and put several of his units in motion behind the advanced corps. In the meantime, Fraser had pushed his men so hard that in six hours, they had closed to within a few miles of St. Clair’s rear guard, comprised of the 11th Massachusetts Regiment of Continentals and men from other units commanded by Colonel Ebenezer Francis.

The Americans were exhausted. Most of the officers and men had slept very little since Burgoyne’s army appeared at Three Mile Point six days earlier, and few had eaten in the prior 24 hours. Convinced that he had put many miles between his army and Burgoyne’s, St. Clair called the main body to a halt at noon near the tiny settlement of Hubbardton, about 20 miles southeast of Mount Independence. Surrounded by five hills to the north and west, Hubbardton lay where the road intersected the Crown Point road, which ran to the north and ultimately ended on Lake Champlain’s east bank across from the ruined fortress. The settlement of nine households, the inhabitants of which had fled south with the British approach, was surrounded by “fields of stumps” and partially cleared woods. About a mile north of the intersection was Sargent Hill. The road ran through a saddle on the southwest slope and crossed the Sucker Brook, a small stream running from the northeast to southwest just west of the hamlet. East of the Sucker Brook and 50 feet above the road was high ground known today as Monument Hill. Still farther to the east, across the Crown Point road, was the Pittsford Ridge. Just south of Monument Hill lay a jagged, rocky eminence soaring well over 1,000 feet high called Mount Zion, which featured a north-facing, mostly bare clifftop.

The spent troops lay in the shade along the road, most too tired to eat. St. Clair had received reports of Loyalist activity to the north, and, because Crown Point was held by the British, the Americans could not afford to linger at Hubbardton. Fearing an attack from two directions, St. Clair decided to continue the march to Castleton, leaving behind Colonel Seth Warner and his regiment, along with Colonel Nathan Hale’s 2nd New Hampshire Regiment, to take command of the rear guard when Colonel Francis and his men arrived. As soon as Warner and Francis linked up, they were to follow the rest of the main body to Castleton. St. Clair got the rest of his men back on the road and set out for Castleton and from there to Skenesborough. The main body had gone only a short distance when several officers, including Poor, begged St. Clair to allow the New Hampshire troops to reinforce the rear guard, arguing that they would be quickly overrun if Burgoyne had started a vigorous pursuit. The commanding general refused. After a few minutes march, they asked again, “but without effect.”

By 4:00 p. m. on July 6, Riedesel’s detachment of about a thousand men finally caught up with Fraser’s force. Riedesel told Fraser that Burgoyne had ordered him to support the advanced corps and then continue to Skenesborough. Fraser was angry that Burgoyne had sent the Germans and not the rest of his own men. Plus, the commanding general had not sent food or ammunition or extra surgeons. The aggressive brigadier wanted to keep the pressure on the Americans, but the German general demanded that they halt the pursuit and make camp. Fraser reluctantly agreed though he understood that opportunities to inflict serious damage on a demoralized enemy were rare. Burgoyne had given Fraser “discretionary powers to attack the Enemy where-ever I could come up with them.” He told Riedesel that he intended to do just that, so before halting, the advanced corps units moved 2 miles closer to the enemy, roughly 3 miles west of Hubbardton. The generals agreed that the allies would move at 3:00 a. m. with Fraser’s advanced corps in the lead and Riedesel’s Germans in support. During the short night, the British and German soldiers slept fully clothed on the ground and with their weapons close at hand.

While Fraser and Riedesel formulated their plan for the next day, the American Colonels Warner and Hale waited at Hubbardton until Colonel Francis’s regiment and the sick and stragglers finally appeared late in the afternoon of the 6th. Instead of moving immediately toward Castleton and staying close to the main body, as St. Clair directed, the three colonels met at the cabin owned by farmer John Selleck and decided that their men were too spent to continue their retreat after marching almost nonstop for sixteen hours in the hot and oppressive weather. Plus, they reasoned, while the British were surely following them, they were undoubtedly far behind. They posted sentries along the road, directed the construction of hasty obstacles along the Sucker Brook, and then finally retired for the evening.

Fraser formed up his troops and started down the road at 3:00 a. m. as planned and set off toward Hubbardton. The American sentries arrayed west of the Sucker Brook detected Fraser’s approach at about 5:00 a. m. as they moved through the saddle of Sargent Hill, fired one volley at close range, and then withdrew to rejoin their units. For many of the British soldiers, it was their first time under fire. “I must own,” recalled one young officer, “when we received orders to prime and load, which we had barely time to do before we received a heavy fire, the idea of perhaps a few moments conveying me before the presence of my Creator had its force.”

The rapid approach of Fraser’s men surprised Warner. He had placed the bulk of his men on or near Monument Hill with Francis’s troops and elements of Hale’s regiment occupying forward positions along Sucker Brook. Warner had not been planning for a fight. He had instead been preparing to move his men to Castleton to join the main body. Once the battle began, however, the Americans took advantage of the natural cover provided by felled trees and brush, which were plentiful in the area.

Fraser quickly deployed his units with the advanced guard under Major Robert Grant in the center, supported by the light infantry under Lord Balcarres on the left, with Acland’s grenadiers in reserve. Fraser accompanied Grant as they fought the Americans, who were “aided by logs and trees.” Hale’s New Hampshire regiment bore the brunt of the British attack and fell back shortly after the first shots were fired, but not before one of their volleys killed Grant. Fraser personally led the light infantry and attacked Francis’s men on Monument Hill, and the fighting soon became a contest for the high ground. Acland moved to assist the hard-pressed companies of the 24th Foot along the Sucker Brook. They succeeded in pushing the American defenders back, and Fraser then ordered Acland’s grenadiers to maneuver around the American left and cut off the Castleton road and the most direct route to St. Clair and the main body. Despite being outmaneuvered by Fraser, the Americans fought well and hard under Warner’s and Francis’s leadership.

After multiple attacks on Monument Hill, Fraser finally succeeded in pushing the Americans back to a lower hill a couple of hundred yards to the east just across the Castleton road. There Warner set up another defense along a log fence, and the Americans poured volley after volley into the British soldiers on the crest of Monument Hill. Warner sensed that Fraser’s units were in some disarray even though they had gained the high ground of Monument Hill, so he ordered a counterattack on the British left flank.

Riedesel and the main body of the German troops had also begun their march that morning at 3:00 a. m. but quickly fell well behind the hard-marching units of the advanced corps. As they approached Hubbardton, Riedesel heard musket fire and hurried a smaller detachment of his troops forward to assist Fraser. At the same time, a messenger arrived from the brigadier urging his colleague to rush to his aid. As the German troops approached the battlefield unnoticed by the Americans, Colonel Francis led his regiment back onto Monument Hill to turn Fraser’s left. The tough New Englanders succeeded in pushing back the British main line consisting of the 24th Foot and the Light Infantry. Fraser’s left was soon hard pressed, and it began to look like the American forces might turn the flank and force the British to fall back. Fraser immediately dispatched another messenger to Riedesel, urging him on. Just as Francis was about to push his momentary advantage, Riedesel’s 180-man detachment arrived on the road. It was 8:30 a. m. He immediately and correctly assessed the situation and identified the threat to Fraser’s left. With the German band playing martial tunes, Riedesel sent into the fight each of his units as they arrived on the battlefield. At the same time, Fraser ordered Balcarres and his light infantry to retake Monument Hill with the bayonet and Acland’s grenadiers along with a detachment of light infantry, having completed their flanking movement, hit Warner on his left.

Francis continued to stubbornly hold his position, but now the weight of numbers began to tell. With the combination of Riedesel’s timely arrival with his Jäger, grenadiers, and light infantry, along with Balcarres’s bayonet attack, the Americans were finally forced to fall back, a retreat that quickly turned into a rout. One Braunschweig officer recalled that many of the “retreating enemy discarded his weapons and equipment, an occurrence that afforded certain of our men a large quantity of booty.” Warner, having successfully faced Acland’s flank attack, was soon forced to withdraw to the east. The German attack was so successful that the Americans withdrew before the rest of Riedesel’s force could join the engagement. Riedesel had arrived just in time, and his fortuitous deployment of the light infantry and grenadiers defeated the Americans relieving Fraser’s hard-pressed advanced corps. By 10:00 a. m., the fighting had ended.

As the Americans retreated to the east over the Pittsford Ridge, they left behind more than 130 killed and wounded, including Colonel Francis, who died while trying to reform his fleeing troops after the German attack. More than two hundred Americans were captured, including Colonel Hale, and to the Germans looked “more like bandits than soldiers.” The allied detachment suffered more than 150 casualties, including Major Grant killed in action and the wounding of both Acland and Balcarres. Warner’s regiment retreated east and reformed at Manchester along with other survivors of the battle. The rest of the surviving rear guard rejoined St. Clair and the main body.

The first real battle of the campaign was over, and the casualties were high in proportion to the numbers engaged. Both sides had fought well. The professionalism of the British was telling in the way they deployed and outmaneuvered the Americans. Still, the American troops stood up to the regulars for most of the battle, only giving way with the surprise arrival of Riedesel’s infantry and grenadiers. Francis and Warner had done their job well, though at a very high cost. Fraser and Riedesel both agreed that they were in no condition to follow up their success by continuing the pursuit.