Potentially a major, advance in air warfare, the Gotha bomber was Germany’s major weapon in her attempt to subdue England’s civilian population in World War I. From it arose the misguided belief that terror bombing could win wars.

The first Hague Peace Conference in 1899 had banned the dropping of projectiles from balloons but only for a five-year period, and before 1914 the popular press and fiction writers had foreseen air attacks on cities. London’s vulnerability caused a panic in 1913.83 After war began, humanitarian considerations caused little hesitation. The French bombed Ludwigshafen in 1914, and they and the British continued to raid enemy border towns into 1915–16, although neither had yet developed specialized bomber aircraft and the damage caused was slight. From Germany, only Zeppelin airships could reach London, and they came under the German navy. Gradually Wilhelm – who had scruples about targeting historic buildings and his cousins’ palaces, while the Chancellor was worried about neutral public opinion – ceded to the navy’s enthusiasm, and raids on London began on 31 May 1915. For some months the British had no answer, but during 1916 new BE2C aircraft arrived that climbed higher and were stable at night, and fired incendiary ‘Buckingham’ bullets. Supported by better anti-aircraft guns, searchlights, and an improved ground observer system, they shot down so many Zeppelins that from September 1916 raids on London ceased. Because of raw-material shortages the airships’ skin was no longer rubberized, and their ribs consisted of wood rather than aluminium, making them even more flammable. The danger seemed over, and in early 1917 the British authorities were winding down their civil defence arrangements.

But the Zeppelins prepared the way for bombing by aircraft. German engineers had been working on the Gotha G-IV bomber since the start of the war, and the OHL wanted it ready for raids to coincide with unrestricted submarine warfare. London, 175 miles from the Gothas’ bases in Belgium, fell within their 500-mile range. Unlike French cities, it could be approached over water, without ground defences, and the Thames estuary provided a conspicuous guideline. Gothas carried a smaller payload than did Zeppelins, but they were faster (87 mph), higher (up to 10,500 feet), more heavily armed (carrying three machine guns), and harder to shoot down. Moreover, whereas the British decrypted the Zeppelins’ wireless code and always had warning of their arrival, the first daylight Gotha raids (codenamed Operation Türkenkreuz) were unanticipated. They killed and injured 290 people at Folkestone on 25 May, and on 13 June they killed and injured 594 in bombing centred on London’s Liverpool Street Station and the East End, including eighteen children at the Upper North Street school in the East India Dock Road; on 7 July another raid on the capital claimed 250 more casualties. By this stage there was media uproar and tense discussion in the War Cabinet. Two fighter squadrons returned from the Western Front (over Haig’s protests) – and a new agency, the London Air Defence Area (LADA), was created under Major Edward B. Ashmore, a gunner moved from Flanders. Ashmore added another barrier of fighters east of London and altered their tactics so that they attacked the Gothas in groups rather than singly, and the same bad weather that bedevilled British troops in Belgium assisted him. In three raids during August the Gothas failed to reach London, and in the last they lost three aircraft, one to AA fire and two to fighters. Perhaps prematurely, they switched to night attacks.

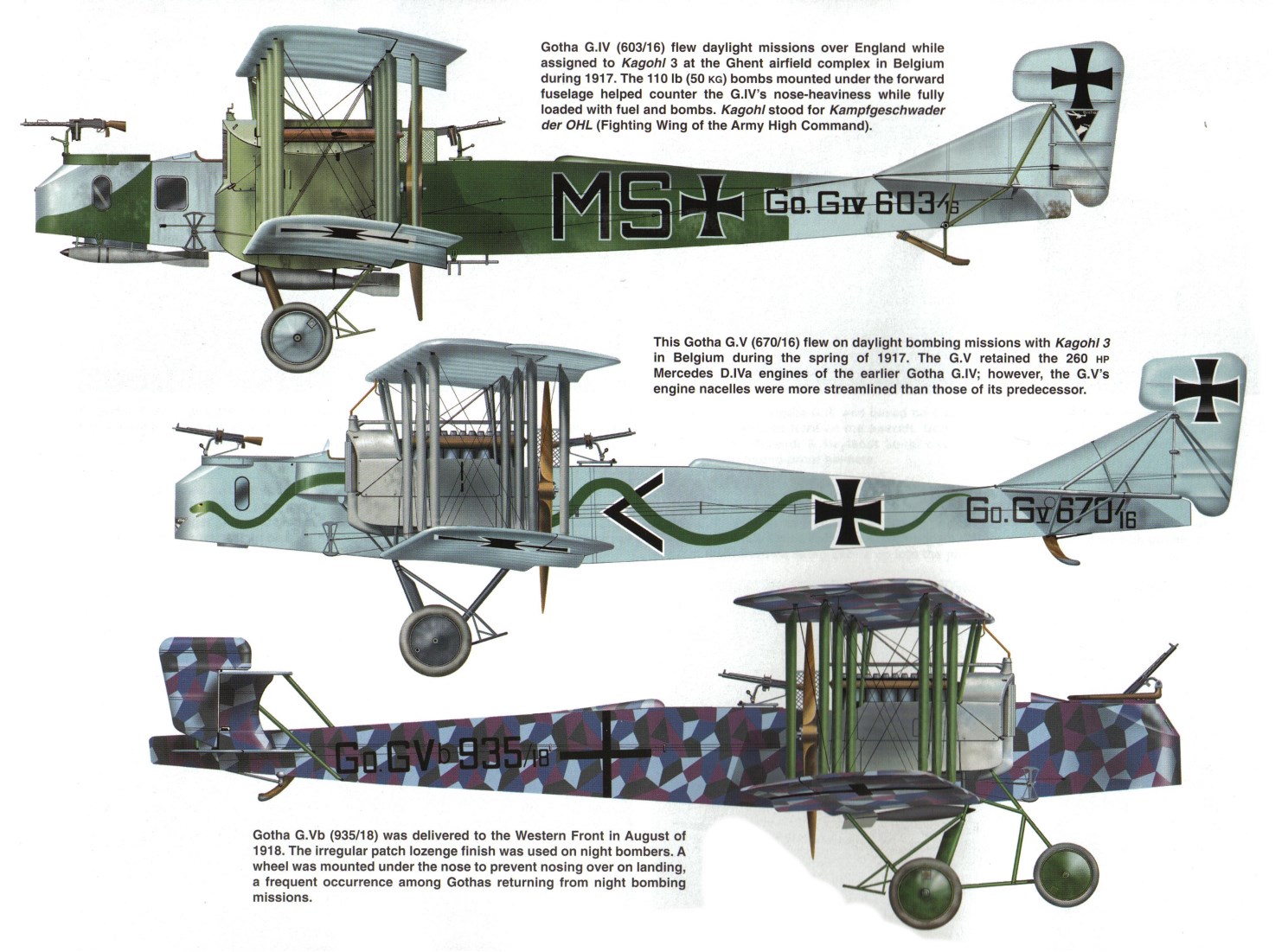

By far the most famous German bombers of the war were the Gotha G. IV and G. V biplanes, which carried out highly successful raids on London in the summer of 1917. They were derived from the earlier Gotha G. II and G. III, which were designed by Hans Burkhard and introduced in 1916. The former proved to be underpowered with its twin 220 hp Benz inline motors, limiting production to just ten aircraft. The latter, however, were powered by two 260 hp Mercedes inline engines and could carry a bomb load of approximately 1,100 lbs. The G. III was also the first bomber that attempted to provide the tail gunner with the ability to fire downward as well as laterally and upward. Replaced on the Western Front fairly quickly by the much-improved G. IV, the G. III was transferred to the Balkans after Romania entered the war against Germany and Austria-Hungary.

The G. IV was introduced in late 1916 and formed the nucleus of Heavy Bomber Squadron No. 3, which by war’s end was to drop more than 186,000 lbs of bombs on London in a series of raids that began with a daylight raid on 25 May 1917. With a wingspan of 77 ft 9.25 in., a length of 38 ft 11 in., and a loaded weight of 7,997 lbs, the G. IV was capable of carrying between 660 and 1,100 lbs of bombs, depending on the mission and the amount of fuel carried on board. In order to have maximum range for the attacks on London, for example, the G. IV carried just 660 lbs of bombs. One of the chief reasons for its success was that its twin 260 hp Mercedes D. IVa inline motors (configured in a pusher arrangement) enabled it to reach a maximum speed of 87 mph and to operate from a service ceiling of 6,500 m (21,325 ft)-a height that was beyond the capabilities of the home defense aircraft used by the British. As a result of the raids, the British were forced to divert top-of-the-line fighters to home defense, forcing the Gothas to switch to nighttime raids. The G. V was a heavier version that had a better center of gravity and featured an improved tail gunner firing arrangement. All versions of the Gothas had a three-man crew. Although precise production figures are not available, it is estimated that 230 G. IVs entered service in 1917. Total production probably exceeded 400, of which forty airframes produced by L. V. G. were supplied to Austria-Hungary and equipped by Oeffag with 230 hp Hiero inline engines.

Kagohl 3 was still carrying out raids on French ports and over the front, but casualties were mounting at an alarming rate. At the beginning of February, Ernst Brandenburg returned to take command again, but after one look at what remained of the England Geschwader he had the unit taken off operations to re-organize and re-equip. By the spring of 1918, Kagohl 3 was once more flying combat missions over France and the western front, but they did not attack England again until 19 May.

The raid on 19-20 May was the largest to be mounted against Britain during the whole war, 38 Gothas and three R-planes flying the mission. From 2230 until long after midnight the bombers streamed across to London, and destruction was extensive with over a thousand buildings damaged or destroyed. But the Gothas paid a fearful price. Only 28 of those that took off actually attacked England; fighters claimed three victims, anti-aircraft fire accounted for three more, and one crashed on its return flight.

As had happened with the GIV, the performance of the GV deteriorated as loads increased and serviceability declined, and the 19 May raid had been carried out from only about 5,500ft, whereas earlier night missions with GV’s had been at over 8,000ft. Bombing at such low levels was bound to be expensive.

By June 1918 new types of Gotha were beginning to arrive at Kagohl 3. The GVa and GVb both had shorter noses than the normal GV, box-tails with twin rudders instead of a single fin and rudder, and auxiliary landing wheels under the nose or at the front of each engine nacelle. The GVb could carry a useful load of 3,520lb, 8031b more than earlier models, but its performance was otherwise no better and in some respects inferior. Since the GIV was now obsolete, these aircraft were being supplied to the Austrians for use on the Italian front, or to training squadrons in Germany.

At the end of May the England Geschwader were switched exclusively to targets in France in support of the German spring offensive, including Paris and Etaples, on the French coast. Later they were diverted to tactical targets near the front as the Allies counter-attacked, and the squadron inevitably suffered catastrophic losses. By November it was all over, however, and grandiose schemes to renew the raids on England in 1919 came to nothing as Germany sued for peace.

The casualties suffered by Kagohl 3 at the end of hostilities totalled 137 dead, 88 missing and over 200 wounded. On raids against England alone, 60 Gothas were lost—almost twice the basic strength of the unit. But the Gotha threat kept two British front line fighter squadrons at home at any one time and thereby indirectly benefited the German Air Force in France and Flanders.

Siegfried Sasson, the war poet, observed an air raid – in his case of the Gotha raid of the 17th August 1917 that attacked the City of London. It warrants a paragraph in his “Memoirs of an Infantry Officer” “When my taxi stopped in that narrow thoroughfare, Old Broad Street, the people on the pavement were standing still, staring up at the hot white sky. Loud bangings had begun in the near neighbourhood, and it was obvious that an air-raid was in full swing. This event could not be ignored; but I needed money and wished to catch my train, so I decided to disregard it. The crashings continued, and while I was handing my cheque to the cashier a crowd of women clerks came wildly down a winding stairway with vociferations of not unnatural alarm. Despite this commotion the cashier handed me five one-pound notes with the stoical politeness of a man who had made up his mind to go down with the ship. Probably he felt as I did—more indignant than afraid; there seemed no sense in the idea of being blown to bits in one’s own bank. I emerged from the building with an air of soldierly unconcern; my taxi-driver, like the cashier, was commendably calm, although another stupendous crash sounded as though very near Old Broad Street (as indeed it was). “I suppose we may as well go on to the station,” I remarked, adding, “it seems a bit steep that one can’t even cash a cheque in comfort!” The man grinned and drove on. It was impossible to deny that the War was being brought home to me. At Liverpool Street there had occurred what, under normal conditions, would be described as an appalling catastrophe. Bombs had been dropped on the station and one of them had hit the front carriage of my noon express to Cambridge. Horrified travellers were hurrying away. The hands of the clock indicated 11.50; but railway-time had been interrupted; for once in its career, the imperative clock was a passive spectator. While I stood wondering what to do, a luggage trolley was trundled past me; on it lay an elderly man, shabbily dressed, and apparently dead. The sight of blood caused me to feel quite queer. This sort of danger seemed to demand a quality of courage dissimilar to front-line fortitude. In a trench one was acclimatised to the notion of being exterminated and there was a sense of organised retaliation. But here one was helpless; an invisible enemy sent destruction spinning down from a fine weather sky; poor old men bought a railway ticket and were trundled away again dead on a barrow; wounded women lay about in the station groaning. And one’s train didn’t start. . . .”