Army Group South, 5-29 October 1944

RETREAT TO THE MURESUL—CRISIS IN HUNGARY

Hungarian Second Army advanced again on 6 September, but not as fast as it had the day before. Sixth Army, which had taken command of Eighth Army’s right flank corps, reported that the Russians were in the Oitoz Pass and, off the army’s south front, were already through the Predeal Pass and assembling at Brasov. Friessner authorized the army to start back during the night if the pressure became too great. He told Guderian that the Hungarians could not be expected to reach the Turnu Rosu Pass; the Rumanians had asked for Russian help. He had talked to the Hungarians and they were agreed on going back to a shorter line.

The next day the Hungarian offensive came to a standstill. The effect of its first two days’ success could be observed farther south. Soviet Sixth Tank Army, which had been going toward the Iron Gate, had stopped and turned north. One of its mobile corps was crossing the Turnu Rosu Pass, another was heading into the Vulcan Pass. By noon the lead elements were through the Turnu Rosu and in Sibiu, forty miles from the Hungarian front Friessner then decided to stop Hungarian Second Army, take it into a defensive line, and back it up with all the German antitank weapons that could be scraped together. Orders went out to Eighth and Sixth Armies to start withdrawing that night. During the night the Operations Branch, OKH, tried to interpose an order from Hitler forbidding the withdrawal. When the army group answered that it had already begun, the Operations Branch replied that Hitler “had taken notice” of the withdrawal to the first phase line but reserved all subsequent decisions to himself.

Five days earlier Hitler had personally instructed Friessner to get ready to fall back some forty miles farther west than the proposed line on the Muresul River. In the meantime he had changed his mind, because he was determined to hold onto his last legitimate ally, Hungary, and because he was arriving at a new and novel estimate of Soviet strategy.

The first reason was the more immediate. Hungary, never a pillar of strength in the German coalition, had since Rumania capitulated been in a state of acute internal political tension. Horthy had dissolved all political parties and had declared his loyalty to Germany. His first impulse had seemed to be to seize the opportunity to annex the Rumanian parts of Transylvania, to which Hitler was only too happy to agree after Rumania declared war. But by 24 August the internal condition of Hungary appeared so uncertain that the OKW moved two SS divisions in close to the capital to be ready to put down an anti-German coup.

The events of the next few days, however, were at least superficially reassuring. The military in particular, appearing to be loyal to the alliance, set about mobilizing their forces for the war against their ancient enemy Rumania with, under the circumstances, surprising energy. The appointment on 30 August of Col. Gen. Geza Lakatos as Minister President to replace Sztojay, who was sick, and the appointments to his Cabinet preserved the hold inside the Hungarian Government which the Germans had established in the spring.

On the other hand Horthy kept out representatives of the radical rightist, fanatically pro-German Arrow-Cross Party.

The first overt alarm was raised on 7 September when, in a flash of panic touched off by a false report that the Russians were in Arad on the undefended south border 140 miles from Budapest, the Hungarian Crown Council met in secret and later, through the Chief of Staff, presented an ultimatum to the OKH: if Germany did not send five panzer divisions within twenty-four hours Hungary would reserve the right to act as its interests might require. Guderian called it extortion but gave his word to defend Hungary as if it were part of Germany and announced that he would send a panzer corps headquarters and one panzer division. Later he added two panzer brigades and two SS divisions, bringing the total to roughly the five divisions demanded. Because Hungary was in so shaky a condition Hitler refused to sacrifice the Szekler Strip even though Friessner and the German Military Plenipotentiary in Budapest assured him that the Hungarians were reconciled to losing the territory.

On 9 September Friessner went to Budapest where he persuaded Horthy to put his agreement to the withdrawal in writing. The impressions he received from talking to Horthy, Lakatos, and the military leaders were so disturbing that he decided to report on them to Hitler in person the next day. At Fuehrer headquarters Friessner learned the second reason why Hitler did not want to give up the Szekler Strip. He had concluded that having broken into the Balkans (Third Ukrainian Front had crossed into Bulgaria on 8 September), the Soviet Union would put its old ambitions—political hegemony in southeastern Europe and control of the Dardenelles—ahead of the drive toward Germany. In doing so, it would infringe on British interests and the war would turn in Germany’s favor because the British would realize they needed Germany as a buffer against the Soviet Union.30 Since the withdrawal had started, he agreed by the end of the interview to let the army group go to the Muresul on the conditions that the line be adjusted to take in the manganese mines at Vatra Dornei and that it be the winter line. He also decided, after hearing Friessner’s report, to “invite” the Hungarian Chief of Staff for a talk the next day.

In Budapest on the 10th Horthy conferred with a select group of prominent politicians, and a day later informed the Cabinet that he was about to ask for an armistice and desired to know which of its members were willing to share the responsibility for that step. The vote went heavily against him—according to the account the Germans received at the time all but one against and, according to his own later statement, three for him. The Cabinet then demanded his resignation. He refused; or, as he put it in his Memoirs, he decided not to dismiss the Cabinet.

Either way, when the Hungarian Chief of Staff went to Fuehrer headquarters on the 12th he went as an ally. The day’s delay had mightily aroused Hitler’s suspicion, and he told the Hungarian military attaché that he had no further confidence in the Hungarian Government. The Chief of Staff’s visit went off, as Antonescu’s had in August, in mutual complaints and recriminations that were finally obscured by a thick fog of more or less empty promises. On his departure Guderian gave him a new Mercedes limousine, which came in handy a few weeks later when he went over to the Russians.

HITLER PLANS A COUNTEROFFENSIVE

Army Group South Ukraine completed the withdrawal to the Muresul on 15 September. Tolbukhin’s armies were temporarily out of the way in Bulgaria, and Malinovskiy’s advance from the south was developing more slowly than had been expected. His tanks and trucks had taken a mechanical beating on the trip through the passes. On the other hand, a new threat was emerging on the north where Fourth Ukrainian Front on 9 September had begun an attempt to break through First Panzer Army and into the Dukla Pass in the Beskides of eastern Czechoslovakia and toward Uzhgorod. Behind that sector of the front the Germans were at the same time having trouble with an uprising in Slovakia in which the Minister of War and the one-division Slovakian Army had gone over to the partisans.

While Friessner was at Fuehrer headquarters Hitler had instructed him to use offensively the new divisions being sent. He wanted them assembled around Cluj for an attack to the south to smash Sixth Tank and Twenty-seventh Armies and retake the Predeal and Turnu Rosu Passes. Friessner issued the directive on 15 September, but the prospects of an early start were not good. Hitler had some of the reinforcements stop at Budapest, in readiness for a political crisis there.

At the front, the Hungarians, who had not done badly against the Rumanians, were disinclined toward becoming earnestly embroiled with the Russians. To give them some stiffening, the Army group merged Hungarian Second Army with Sixth Army to form the Armeegruppe Fretter-Pico under the Commanding General, Sixth Army, Fretter-Pico. On the 17th Fretter-Pico reported that Second Army was in a “catastrophic” state and that one mountain brigade had run away.

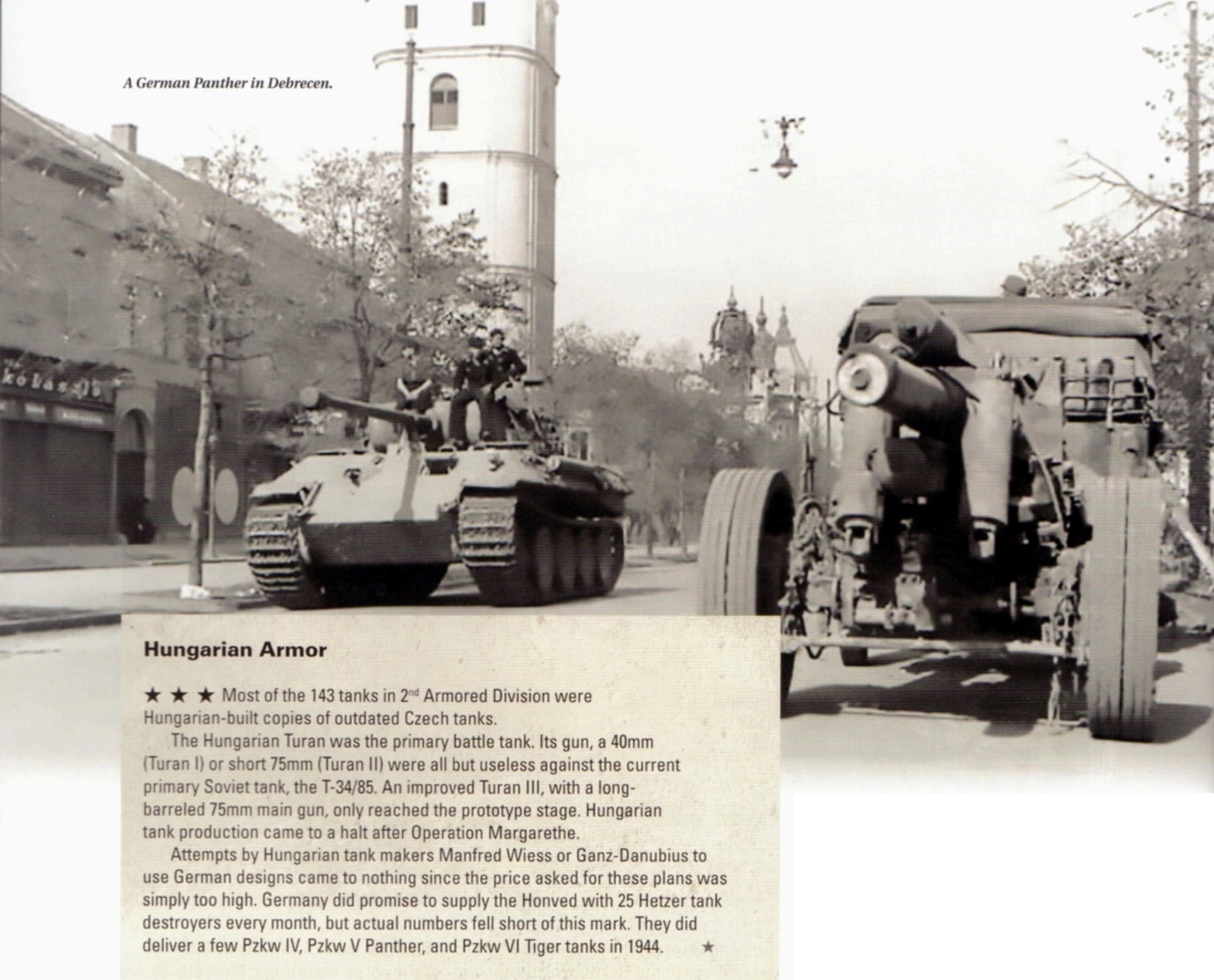

TANK BATTLE AT DEBRECEN

At mid-month the Stavka also gave new orders. It directed Tolbukhin, still occupied in Bulgaria, to give Forty-sixth Army to Malinovskiy, and it transferred the Cavalry-Mechanized Group Pliyev from First Ukrainian Front. It instructed Malinovskiy to send his main thrust northwest from Cluj toward Debrecen, the Tisza River, and Miskolc, expecting him thereby both to benefit from and assist Fourth Ukrainian Front’s advance toward Uzhgorod. For a week, beginning on 16 September, Sixth Tank and Twenty-seventh Armies tried unsuccessfully to take Cluj, which, because of Hitler’s plan, was exactly the place Army Group South Ukraine was most determined to hold.

Friessner was far short of the strength both to fight the battle at Cluj and establish a front west of there. On 20 September a minor Russian onslaught threw back to Arad the Hungarians covering his flank on the west, and the following day they gave up the city without a fight. Thereafter the Hungarian General Staff activated a new army, the Third, composed mostly of recruits and recently recalled reservists, to hold a front on both sides of Arad. Reluctantly, it agreed to put the army under Army Group South Ukraine.

Losing Arad sent another wave of panic through Budapest even though the army group (redesignated Army Group South at midnight on 23 September) was certain that Malinovskiy did not yet have enough strength at Arad to attempt to strike out for Budapest. The German Military Plenipotentiary in Budapest reported on the 23d that the Hungarian command had completely lost nerve. It had pulled First Army back to the border, it intended to move two divisions of Second Army west, and it wanted to withdraw Third Army to the Tisza River. The OKH promptly whipped the Hungarians into line and had their orders rescinded. “In view of the Hungarian attitude,” Guderian then sent several strong panzer units to “rest and refit” just outside Budapest.

The Hungarians’ nervousness was premature, but not by much. Malinovskiv was shifting his main force west to the Arad-Oradea area, and Army Group South had too few German troops to keep pace. On the 24th, when Friessner called for reinforcements, the Operations Branch, OKH, replied that it recognized the need the reason the army group had not been given any so far was that Hitler was still convinced the Soviet Union would first attempt to settle affairs in the Balkans on its own terms.

On the 25th elements of Sixth Tank Army, shifted west from Cluj, began closing in on Oradea. Friessner informed Hitler that the next attack would come across the line Szeged-Oradea, either northwest toward Budapest or north along the Tisza to meet Fourth Ukrainian Front’s thrust through the Beskides. He could not stop it without more armor and infantry. Operations Branch, OKH, replied that Hitler intended to assemble a striking force of four panzer divisions around Debrecen for an attack south, but that could not be done before 10 October. Until then Friessner would have to deploy the forces he had in trying to check the Russians in the Szeged-Oradea area.

By the end of the month Hitler had fleshed out his plan for the proposed striking force. The attack would go south past Oradea and then wheel west along the rim of the Transylvanian Alps to trap the Russians north of the mountains. After mopping up, Army Group South could establish an easily defensible winter line in the mountains. For a while it appeared that he might have time enough to put the striking force together. After taking Oradea on 26 September and losing it two days later when the Germans counterattacked, Second Ukrainian Front reverted to aimless skirmishing.

The Stavka was also looking for a quick and sweeping solution. On its orders, Malinovskiy deployed Forty-sixth Army, Fifty-third Army, and the Cavalry-Mechanized Group Pliyev on a broad front north and south of Arad for a thrust across the Tisza to Budapest. To their right Sixth Tank Army, now a guards tank army, was to strike past Oradea toward Debrecen, the Tisza, and Miskolc, there to meet a Fourth Ukrainian Front spearhead that would come through the Dukla Pass and by way of Uzhgorod. The pincers, when they closed, would trap Army Group South and First Panzer and Hungarian First Armies. Twenty-seventh Army, Rumanian First Army, and Cavalry-Mechanized Group Gorshkov were to attack toward Debrecen from the vicinity of Cluj. Timoshenko co-ordinated for the Stavka.

The plan was ambitious, too ambitious. Men and matériel for an extensive build-up were not to be had at this late stage of the general summer offensive; both fronts were feeling the effects of combat and long marches; and their supply lines were overextended. Because of the difference in gauges, the Rumanian railroads, if anything, were serving the Russians less well than they had the Germans, and Second Ukrainian Front had to rely mainly on motor transport west of the Dnestr. Malinovskiy’s broad-front deployment gave him only about half the ratio of troops to frontage usual for a Soviet offensive. As a prerequisite for the larger operation Fourth Ukrainian Front’s progress through the Dukla Pass was not encouraging; it had been slow from the start and at the end of the month the offensive was almost at a standstill.

After the turn of the month the Soviet attack into the Dukla Pass began to make headway, partly because Hitler had taken out a panzer division there for his striking force, and on 6 October the Russians took the pass. That morning Malinovskiy’s armies attacked. Hungarian Third Army melted away fast. At Oradea, however, Sixth Guards Tank Army met Germans and was stopped.

On the 8th, as his left flank was closing to the Tisza, Malinovskiy turned Cavalry-Mechanized Group Pliyev around and had it strike southeast behind Oradea. That broke the German hold. By nightfall a tank corps and a cavalry corps stood west of Debrecen, and Friessner, over Hitler’s protests, ordered the Armeegruppe Woehler to start back from the Muresul line.

The army group still had one panzer division stationed near Budapest and another, the first of the proposed striking force, at Debrecen. On 10 October the divisions attacked east and west below Debrecen into the flanks of the Soviet spearhead. Late that night their points met. They had cut off three Soviet corps. The army group envisioned “another Cannae,” and Hitler ordered Armeegruppe Woehler to stop on the next phase line.

The next day, when Sixth Guards Tank Army put up a violent fight to get the corps out, who had trapped whom began to become unclear. The flat Hungarian plain became the scene of one of the wildest tank battles of the war. Malinovskiy reined in on his other armies. By the 12th the Russians in the pocket were shaking themselves loose, and Friessner ordered Armeegruppe Woehler to start back again. On the 14th the Russians were clearing the pocket, and Army Group South began concentrating on getting a front strong enough to keep them from going north once more. In the Beskides Fourth Ukrainian Front was moving slowly again south of the Dukla Pass and trying to get through some of the smaller passes farther east.

HORTHY ASKS FOR AN ARMISTICE

During the battle at Debrecen the Germans were aware that they were, as someone in OKH put it, “dancing on a volcano.” They sensed that in Budapest a break might come any day, almost any hour. Their suspicion was well founded. In late September Horthy had sent representatives to Moscow to negotiate an armistice, and on 11 October they had a draft agreement completed and initialed without a fixed date. To be ready for any sudden moves, Hitler had sent in two “specialists,” SS General von dem Bach-Zelewski and SS Col. Otto Skorzeny. Von dem Bach had long experience in handling uprisings, most recently at Warsaw. Skorzeny commanded the daredevil outfit that had rescued Mussolini.

The crisis in Hungary resolved itself less violently than the Germans expected. As Hungarian head of state for a generation, Horthy had accumulated tremendous personal prestige, but his authority had declined, and his political position was badly undermined. In the Parliament during the first week of October the parties of the right formed a prowar, pro-German majority coalition against him. The Army was split; some of the generals and many of the senior staff officers wanted to keep on fighting. On 8 October the Gestapo arrested the Budapest garrison commander, one of Horthy’s most faithful and potentially most effective supporters, and, on the 15th, it arrested Horthy’s son, who had played a leading role in the attempt to get an armistice.

The Soviet Union demanded that Hungary accept the armistice terms by 16 October. In the afternoon of the 15th Radio Budapest broadcast Horthy’s announcement that he had accepted. By then he was acting alone. The Lakatos Cabinet had resigned on the grounds that it could not approve an armistice and Parliament had not been consulted on the negotiations.

The next morning, to the accompaniment of scattered shooting, the Germans took the royal palace and persuaded Horthy to “request” asylum in Germany. In his last official act, under German “protection,” Horthy appointed Ferenc Szalasi, the leader of the Arrow-Cross Party, as his successor. Szalasi, whose chief claim to distinction until then had been his incoherence both in speech and in writing, subsequently had himself named “Nador” (leader), with all the rights and duties of the Prince Regent.

On 17 October Guderian, in an order declaring the political battle in Hungary won, announced that the next step would be to bring all of the German and Hungarian strength to bear at the front. How that was to be accomplished he did not say. In terms of the military situation the victory was one only by comparison with the immediate, total dissolution that would have come if Horthy’s attempt to get an armistice had succeeded. Morale in the Hungarian Army hit bottom. Some officers, including the Chief of Staff, some whole units, and many individuals deserted to the Russians, who encouraged others to do the same by letting the men return home if they lived in the areas under Soviet control.

TO THE TISZA

On the night of 16 October Hitler ordered Army Group South to see the battle through at Debrecen but also to start taking Armeegruppe Woehler back toward the Tisza. Meanwhile, Malinovskiy had reassembled his armor, the two cavalry-mechanized groups and Sixth Guards Tank Army, south of Debrecen. On the 10th the Cavalry-Mechanized Group Pliyev broke through past Debrecen, and two days later it took Nyiregyhaza, astride Armeegruppe Woehler’s main line of communications.

The Armeegruppe, which had also taken command of Hungarian First Army, its neighbor on the left, held a bow-shaped line that at its center was eighty miles east of Nyiregyhaza. Friessner’s first thought was to pull the Armeegruppe north and west to skirt Nyiregyhaza. His chief of staff persuaded him to try a more daring maneuver, namely, to have Woehler’s right flank do an about-face and push due west between Debrecen and Nyiregyhaza while Sixth Army’s panzer divisions, in the corner between Nyiregyhaza and the Tisza, struck eastward into the Russian flank.

The maneuver worked with the flair and precision of the blitzkrieg days. On the 23rd the two forces met and cut off three Soviet corps at Nyiregyhaza. Before Russians could break loose, almost the whole Armeegruppe Woehler bore down on them from the east. In three days the Germans retook Nyiregyhaza. On the 29th the survivors in the pocket abandoned their tanks, vehicles, and heavy weapons and fled to the south.

On that day, too, for the first time in two months, Army Group South had a continuous front. On the north it bent east of the Tisza around Nyiregyhaza and then followed the middle Tisza to below Szolnok, where it angled away from the river past Kecskemet to the Danube near Mohacs and tied in with Army Group F at the mouth of the Drava. But it was not a front that could stand long. The Tisza, flowing through flat country, afforded no defensive advantages—the Russians had easily driven Hungarian Third Army out of better positions than those it held on the open plain between the Tisza and the Danube.