For three decades, the seventeenth-century Mbundu queen, Njinga of Ndongo and Matamba, defended her West African kingdom against the Portuguese with an in-your-face combination of warfare and diplomacy. In short, she was what one observer described, with admiration, as “A Cunning and Prudent Virago.”

When the Portuguese established a trading colony on the coast of what is now modern Angola in 1575, the kingdom of Ndongo was the second largest state in central Africa. Its population of roughly one hundred thousand people lived under the rule of local lords called sobas, who owed their allegiance to the central ruler, the ngola, who lived in the capital city of Kabasa.

At first, relations between the Portuguese and Ndongo were friendly. The ruler at the time, Ngola Kiluanji, welcomed trade with Europeans and his kingdom flourished in the early days of the Portuguese slave trade. By the time Njinga was born in 1582, Ndongo was at war with Portugal. The two states would remain in conflict for her entire life.

Njinga was a granddaughter of Ndongo’s founder and the kingdom’s fourth ruler. According to her biographers, she displayed intellectual and physical prowess as a child. She showed particular talent for wielding the battle-axe that was the royal symbol of Ndongo. With her father’s approval, she sat in on his judicial and military councils and studied the military, political, and ritual arts taught to the sons of Mbundu rulers. At the same time, as a privileged young woman at court, she paid careful attention to her appearance, which she would use as a weapon of another sort throughout her career. At some point during the reigns of her two immediate predecessors—her father, Mbande a Ngola, and her brother, Ngola Mbande—Njinga became a war leader in her own right.

In 1617, Ngola Mbande overthrew their father and named himself ngola. In order to consolidate his position, he killed all potential rivals, including Njinga’s only son. To prevent the birth of new rivals, he ordered Njinga and her two sisters sterilized: a horrifying process in which oils combined with various herbs were thrown “while boiling onto the bellies of his sisters, so that, from the shock, fear & pain, they should forever be unable to give birth.” It appears to have worked: none of the three women gave birth thereafter.

With his position as ruler secure, Ngola Mbande set out to restore his kingdom to the wealth and power it enjoyed under his predecessors. He fought a losing battle against the Portuguese for four years.

In 1621, a new Portuguese governor, João Correia de Sousa, arrived in Luanda, in the colonial capital. Hoping a change of governor offered a chance for peace, Mbande sent Njinga to Luanda to negotiate a treaty with the Portuguese.

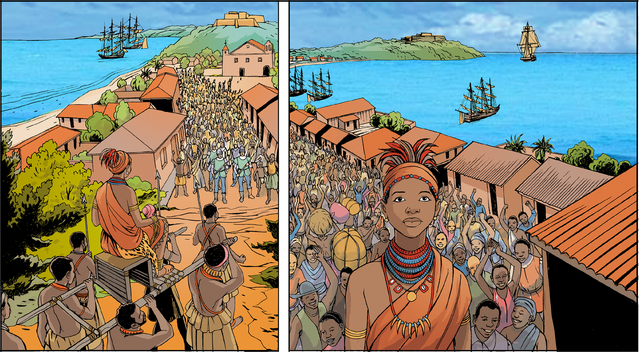

Fully conscious of the power of symbols, Njinga arrived with an impressive entourage of soldiers, musicians, slaves, and waiting women, and a new title, Ginga Bande Gambole—Njinga Mbande, official envoy.

Governor de Sousa was equally aware of the value of symbols in diplomatic situations. When Njinga entered his audience chamber, he greeted her from the governor’s throne and gestured for her to sit on a cushion on the floor before him—the typical arrangement when African notables met with the Portuguese governor. Njinga refused to take the posture of a supplicant. She gestured for a female slave to come forward. The woman knelt on her hands and knees. Njinga sat on the woman’s back as if she were a human chair. She was ready to negotiate, equal to equal.

Njinga remained in Luanda for several months and negotiated a peace treaty on her brother’s behalf. For a brief time, her mission appeared to be a success, but neither side honored their agreements. Soon Ndongo and the Portuguese were at war once more.

In spring of 1624, Ngola Mbande died. Everyone agreed he was poisoned. The Portuguese said it was murder and pointed at Njinga. Angolan oral history claims he committed suicide in a moment of despair. Either way, Mbande made arrangements before his death for the care of the young son who was his heir. Recognizing the dangers of a child ruler, for both the young king and the kingdom, Ngola Mbande divided the responsibility in two parts. He named Njinga regent, with the power of governing Ndongo in the boy’s minority. He put the boy under the guardianship of an ally named Kaza. In theory it was a brilliant solution to an age-old problem, but it didn’t take into account Njinga’s ambition. Njinga convinced Kaza to turn the boy over to her, using a combination of lavish presents and an offer of marriage. Once she had control of the child, she poisoned him, then pushed through her immediate election as the new ngola of Ndongo.

Njinga spent the next thirty years in warfare and diplomatic wrangling with the Portuguese. Between 1626 and 1655, the queen commanded her own forces against the Portuguese army. In 1630, she conquered a new kingdom, Matamba, which she used as a base for attacks on settlements under Portuguese control.

A new player entered the political and economic scene in 1641: the Dutch East India Company.

On April 20 of that year, twenty-two Dutch ships attacked and conquered the Portuguese colonial capital of Luanda. Njinga celebrated as soon as she heard the news, then sent ambassadors to propose an alliance. The Dutch were willing allies. Together Njinga and the Dutch almost brought Portuguese rule in Angola to an end.

By August 1648, Njinga and the Dutch seemed on the verge of driving the Portuguese out of Angola. But reinforcements were on the way from Rio de Janeiro in the Portuguese colony of Brazil. A fleet of fifteen ships and nine hundred men arrived in Luanda’s port and bombarded the city with cannon fire. After a few days of heavy shelling, the Dutch East India Company surrendered all Dutch positions in Angola to the Portuguese.

With the Dutch defeated and in flight, Njinga retreated to her base at Matamba, from which she continued her guerilla campaign against the Portuguese and their African allies until 1654. According to one Portuguese observer, she launched at least twenty-nine invasions against sobas in Portuguese Angola and surrounding kingdoms between 1648 and 1650 alone.

Njinga was forty-two years old when she succeeded her brother as the ngola of Ndongo. In December 1657, when she was nearly seventy-five she led her army into battle for the last time. Before the battle she prepared her soldiers—many young enough to be her great-grandchildren—by leading them in the customary war dance, a rigorous military exercise with arrows and spears.

When Njinga died in 1663, she left behind a thriving kingdom, which survived as an independent state until 1909, when the Portuguese finally succeeded in making it part of the colony of Angola.

In the 1960s, Angolan revolutionaries turned to oral traditions about Njinga for inspiration and celebrated her as a national hero who had united her people in an epic struggle against the Portuguese.