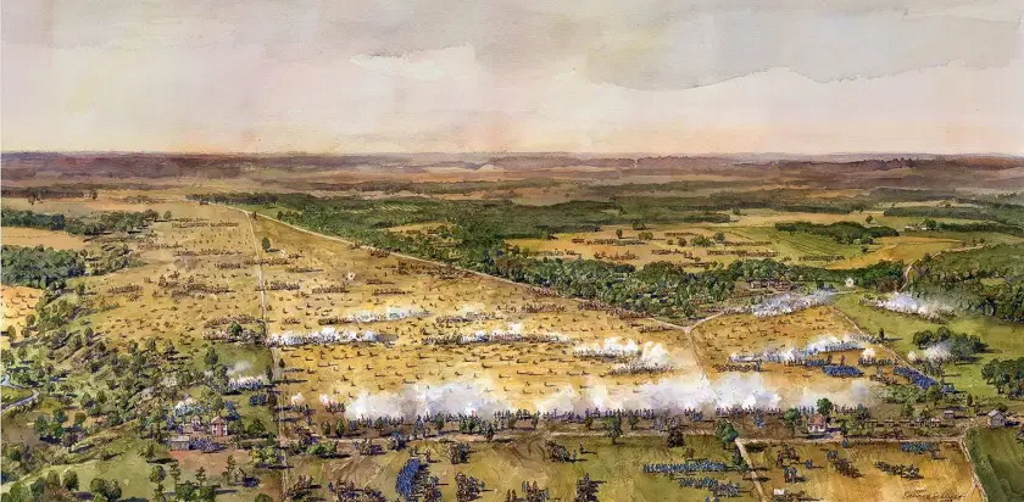

Battle of Malvern Hill; Confederate forces are indicated in red, and Union forces are indicated in blue.

To the Federals’ great good fortune, Lee’s battle plan fell to pieces just as it had at Mechanicsville four days earlier. Jackson applied only artillery to his task, leaving his powerful infantry force standing idle. Huger fumbled his assignment as well, weakly engaging his artillery and none of his infantry. A confused Magruder marched his divisions first one way and then another, and they too failed to fire a shot. Thus the fighting at Glendale was left to just the twelve brigades of Longstreet and A. P. Hill—a severe enough test for the Yankees, to be sure, and nearly more than they could handle.

McCall’s Pennsylvania Reserves, confronting their third fight in five days (after Mechanicsville and Gaines’s Mill) were battle-weary and undermanned. John Reynolds had been captured on June 27 and his brigade was under Colonel Seneca G. Simmons. The division had suffered 1,650 casualties at Gaines’s Mill, a thousand of those from George Meade’s brigade. It was only by chance—a misdirected nighttime march—that the Reserves were not then on Malvern Hill with the rest of the Fifth Corps . . . and only by chance that their posting was at the center of the Glendale defenses.

George McCall’s inexperience, or incompetence, was evident in his postings. His flanks were not covered and he positioned his six batteries too far in advance of supporting infantry. Meade regarded the postings as very faulty and told one of his captains he suspected McCall of being either drunk or ailing and under the influence of opium. The opium charge was not new; the Comte de Paris had raised it at Gaines’s Mill. Truman Seymour’s brigade formed on the left in a large field and well in advance of Joe Hooker’s division to his left. Meade’s brigade was on the right and not tied to Kearny, while Simmons’s lay in reserve. The only other reserve in the Quaker Road sector was one of John Sedgwick’s Second Corps brigades.

Longstreet, guiding on the Long Bridge Road, attacked on a three-brigade front. The Rebels stormed out of the thick woods, driving the Yankee skirmishers before them and aiming for McCall’s exposed gun line. On Seymour’s front two batteries, from the artillery reserve and unused to such close work, pulled back with unseemly haste. There was bitter fighting around the other four batteries; Seymour’s infantry line was breached and his flank turned, and he and most of his men retreated in disorder, leaving a large gap in the battlefront. Joe Hooker was still in a fury about it when he drafted his report: Officers and men of Seymour’s brigade “broke through my lines, from one end of them to the other, and actually fired on and killed some of my men as they passed. Conduct more disgraceful was never witnessed on a field of battle.”

As Longstreet and Hill tried to widen and deepen the breach, the Federals fought to seal it, striking head-on and from both flanks. Seneca Simmons, only days in command of Reynolds’s brigade, led a charge into the gap and was killed. George Meade too rushed into the midst of the fighting. Alanson M. Randol, whose battery was subjected to repeated attacks, remembered seeing Meade pressing his men into the fight, “encouraging & cheering them by word and example.” Then Meade was hit, in the right arm and in the chest. He told Randol he was badly wounded and must leave the field. “Fight your guns to the last, but save them if possible.” Now, of McCall’s three brigade commanders, Simmons was dead, Meade wounded, and Seymour missing in action. A staff man came on a dazed General Seymour behind the lines, on foot, “his hat and clothes pierced by balls. He was alone. I asked him where his Brigade was: he told me it was entirely dispersed.” All twenty-six of the guns on McCall’s front were captured, abandoned, or withdrawn.

Behind the broken front Sumner and Heintzelman pushed reserves forward as fugitives fled past them. The shrill yip of the Rebel yell marked the enemy’s gains, close enough that both Heintzelman and Sumner were grazed by spent bullets. John Sedgwick was nicked twice and his horse killed. Sedgwick’s one brigade then present, under William Burns, was thrust into the breach, and Burns met the challenge as he had at Savage’s the day before. Sumner called on Franklin to return Sedgwick’s other two brigades loaned him, and Franklin did so promptly. Confident now of his own position, Franklin sent along two additional brigades of Richardson’s. To the arriving 15th Massachusetts, Sumner called out, “Go in, boys, for the honor of old Massachusetts! I have been hit twice this afternoon, but it is nothing when you get used to it.” These 11,700 men proved decisive in stemming the breakthrough.

On the northern shoulder of the broken front Phil Kearny reported Rebels attacking “in such masses as I had never witnessed,” a notable appraisal from a soldier of his experience. Guarding his flank was a section of Battery G, 2nd U.S. Artillery, Captain James Thompson, and guarding Thompson was Alexander Hays’s 63rd Pennsylvania. Twice Colonel Hays counterattacked to save the guns. Finally Thompson said he was out of ammunition and must withdraw. “I told him to go ahead and I would give him a good chance,” wrote Hays in a letter home. “Again it was ‘up, 63rd, give them cold steel; charge bayonets, forward, double quick!’ In a flash, yelling like incarnate fiends, we were upon them. . . . Such an onset could not last long, and towards dark we retired, having silenced the last shot.” This drama was witnessed by Kearny, and Alex Hays was flattered by the attention: “Kearny is somewhat hyperbolical in his expressions, but says it was magnificent, glorious, and the only thing that he saw like the pictures made in the papers. . . .”

Sam Heintzelman, rushing back and forth between his divided command, saw that Hooker now had matters in hand, so he focused on Kearny’s needs. He sought out Henry Slocum, whose division on the far right was comparatively idle. Slocum agreed to lend him the New Jersey brigade, Kearny’s old command, and with a shout the Jerseymen rushed into the fight at the double-quick. Another reinforcement was Lieutenant Colonel Francis Barlow’s 61st New York, loaned from Richardson’s division. Barlow wrote, “At a charge bayonets & without firing we went at a rush across the large open field. It was quite dark & very smoky so that we could not distinctly see the enemy in the open ground but they heard us coming & broke & ran. . . .” The 61st ended the day holding its position with the bayonet, its cartridge boxes empty. By then Barlow was leading three regiments as senior officer present.

In the dark woods Kearny was as usual personally (and recklessly) scouting out the fighting. “I got by accident in among the enemy’s skirmishers . . . and was mistaken by a rebel Captain for one of his own Generals,” he wrote his wife; “he looked stupid enough & said to me, ‘What shall I do next, Sir,’ to which I replied . . . ‘Do, damn you, why do what you have always been told to do,’ & off I went.” By leading from the front, his men “know that when matters are difficult, I am at their head, between them & danger—at least showing that I count on being followed,” not exposing them to dangers “I do not share.”

As darkness ended the fighting, George McCall concluded a day of general misfortune by losing his way and stumbling into the enemy lines. He was the second Union brigadier general, after John Reynolds, to be taken prisoner in the Seven Days fighting. This left battle-shocked Truman Seymour in command of the Pennsylvania Reserves and colonels in command of its three brigades.

Glendale cost the two armies a roughly equal number of casualties—3,673 Confederate, 3,797 Federal, plus eighteen guns lost. McCall’s and Kearny’s divisions accounted for almost three-fifths of the Federal total. George Meade’s chest wound proved dangerous but not life-threatening. He recuperated at home in Philadelphia and returned in time for the next campaign. McCall would be exchanged in August, but ill health and his unsteady record at Glendale combined to end his military career.

In the absence of the commanding general, the officer corps improvised very capably at Glendale. Franklin’s rear guard had little to do beyond hunkering down against Jackson’s artillery, and Franklin was prompt and generous in reinforcing McCall. Henry Slocum, not seriously threatened, reinforced Kearny. Heintzelman added to his solid record of leadership, managing a divided command even as he fed reinforcements into McCall’s broken front. Edwin Sumner and John Sedgwick and George Meade were in their element pressing troops into the fighting. Hooker on the left of the break and Kearny on the right continued to show exceptional skills at troop leading, although again Kearny did so in the most reckless manner. “He rides about on a white horse, like a perfect lunatic,” wrote Richard Auchmuty, adding that a posting on Kearny’s staff was decidedly unhealthy. There were some questions about Truman Seymour’s indecisive handling of his brigade, but he would head the Pennsylvania Reserves until the next campaign.

Disaster was averted (narrowly), the army was wounded but intact, and the Quaker Road remained open. Still lacking any guidance from McClellan, his lieutenants continued deciding matters on their own. Convinced that a second day of inaction by Stonewall Jackson was highly unlikely, Franklin sent to Heintzelman to ask how soon his command would clear the road for the rear guard to withdraw. Heintzelman replied that he had no orders to move and should not move without them. Slocum, like Franklin in an exposed position, added his voice for withdrawal, as did Seymour for McCall’s bloodied division. Heintzelman had sent off a staff officer to find McClellan, report on the day’s events, and get his orders. Finally, despairing of hearing from him (the Comte de Paris noted McClellan reading Heintzelman’s dispatch aboard the Galena and making no reply), Heintzelman and Sumner agreed on retreat. Heintzelman summed up: “General McClellan had been down the James River & we had to fall back or be cut off & on our own responsibility.”

Slocum pulled back first, followed by Kearny, Seymour, Sedgwick, and Hooker. Franklin was able to withdraw the rear guard “in parallel” with the others after one of Baldy Smith’s staff rediscovered the woods road General Keyes had found three days earlier. One of Smith’s men wrote in disgust, “We pulled up stakes again in the night and skedaddled.” They were not pursued. “It was after one a.m. when we took the road,” wrote diarist Heintzelman, “& at 2 a.m. were at Gen. Porter’s Hd. Qrs. where I met Gen. McClellan who had just heard of what was going on.”

A staff man on Malvern Hill recalled McClellan “suddenly coming riding hard up the hill in the dark, about 8.30 p.m. I think, & going at once . . . to read the accumulated dispatches.” Earlier, at Haxall’s Landing, McClellan implied to Washington that he was in the midst of the battle: “Another day of desperate fighting. We are hard pressed by superior numbers. . . . If none of us escape we shall at least have done honor to the country. I shall do my best to save the Army.” He asserted bravely he was sending orders to renew the combat the next day at Glendale, “willing to stake the last chance of battle in that position as any other.” But soon enough he found his generals already falling back (without orders, he told the staff disapprovingly). “I have taken steps to adopt a new line. . . .”

At 2:00 a.m. on July 1, McClellan called in topographical engineer Andrew Humphreys and instructed him to lay out lines on Malvern Hill and post the troops coming in from Glendale. “There was a splendid field of battle on the high plateau where the greater part of the troops, artillery, etc. were placed,” Humphreys wrote his wife. “It was a magnificent sight.” If today was to be the Potomac army’s last stand, the place was well chosen.

Malvern Hill was an elevated plateau three-quarters of a mile wide and a mile and a quarter deep that overlooked the James a mile distant. On the west was a sharp drop-off called Malvern Cliffs, and on the east the terrain was wooded and marshy. The Rebels approaching from the north confronted a gradual, open slope leading up to the crest of the hill, where on display was what Alexander Webb called “a terrible array”—the artillery of the Army of the Potomac. Fitz John Porter would be credited with command of the battle fought there that day, but in fact the battle belonged to Henry Hunt, the Potomac army’s chief of artillery.

By midday on July 1 Humphreys had the infantry posted and Hunt had the guns positioned to meet what everyone on Malvern Hill recognized was certain to be yet another assault by the relentless enemy. At an early hour General McClellan appeared on the field and rode the lines. The troops’ welcome inspirited him: “The dear fellows cheer me as of old as they march to certain death & I feel prouder of them than ever,” he told Ellen. “I am completely exhausted—no sleep for days—my mind almost worn out—yet I must go through it.” Going through it would not include taking command of the coming battle, however.

At 10:00 a.m. the Galena again weighed anchor with the general aboard. This time his journey was an hour and a half downstream to Harrison’s Landing, which Commander Rodgers said was the farthest point on the James that the navy could protect the army’s supply line. McClellan spent two hours ashore “to do what I did not wish to trust to anyone else—i.e. examine the final position to which the Army was to fall back.” The Galena’s log showed him returning to Haxall’s Landing at 2:45 that afternoon, and Andrew Humphreys placed him on Malvern Hill at about 4 o’clock, conferring with Porter. McClellan then made a second tour of the lines, after which he remained at the extreme right of the army throughout the period of the heaviest fighting. By the account of his staff officer William Biddle, “We heard artillery firing away off to the left—we were too far to hear the musketry, distinctly. . . .”

Critics would make much of McClellan’s Galena expedition on July 1, accusing him of abandoning his army on the eve of battle, and he was sensitive to the issue. In testimony before the Committee on the Conduct of the War in March 1863, when asked if he boarded a gunboat “during any part of that day,” he replied that he did not remember. During the 1864 presidential campaign cartoonists labeled him “The Gunboat Candidate,” lounging aboard the Galena as his army fought for its life. In fact, McClellan consulted with Porter during one phase of the Malvern fighting, then deliberately distanced himself from active command. The true, lesser known case of dereliction of duty was absenting himself aboard the Galena on June 30 while at Glendale his army did actually fight for its life. At Malvern Hill on July 1, while conforming to the letter of command, George McClellan certainly violated the code of command.

The Fifth Corps’ Morell and Sykes and Hunt’s reserve artillery were posted on Malvern Hill when McClellan arrived at the James on June 30. He shifted Darius Couch’s Fourth Corps division from Haxall’s Landing to Malvern. As finally established, the battlefront facing the advancing Rebels was Morell’s division on the left and Couch’s on the right, a total of 17,800 men. Sykes’s and McCall’s divisions guarded the western flank. The eastern flank was three army corps strong—Heintzelman’s Third, Sumner’s Second, Franklin’s Sixth. John Peck’s Fourth Corps division, with corps commander Keyes, was at the river.

As was now habit, McClellan designated no overall commander when he went off to Harrison’s Landing, so Porter, as the general posted on Malvern Hill when the rest of the army reached there, was recognized by all as commander pro tem—by all but old Sumner. Edwin Sumner reflexively assumed the command whenever McClellan was not in sight (which was often enough during the Seven Days), and at one point during the Malvern fighting he ordered Porter to fall back to a new position. Porter ignored him. On the Federal battlefront were eight batteries, 37 guns. Hunt would bring up batteries from his reserve to where they were most needed. Altogether on the plateau there were 171 guns posted for action or in reserve.

General Lee intended to clear the way for his infantry with a massive artillery barrage from a “grand battery.” But his guns were poorly handled, while the Yankee batteries were expertly handled, and the barrage scheme collapsed. A series of command misunderstandings then sent the Confederate infantry lunging head-on against Malvern Hill. A single powerful blow might have had at least a chance of breaking the Yankee line, but the assaults were disjointed and beaten back one after another. “It was not war—it was murder,” was Confederate general D. H. Hill’s verdict.

Henry Hunt ranged back and forth along the gun line, checking postings and battle damage, pulling out batteries that had exhausted their ammunition and replacing them from his reserve. Twice his horse was killed under him, twice he sprang up calling for a new mount. Hunt understood that reserves would be decisive. He described his thinking: “I gathered up some thirty or forty guns . . . brought them up at a gallop, got them into position as rapidly as possible, and finally succeeded in breaking the lines of the enemy.” His was a masterful performance.

Captain John C. Tidball’s battery was one of those Hunt called up. To his surprise, Tidball found the battery blazing away next to him was commanded by Captain Alanson Randol. He knew Randol had lost his guns at Glendale after a savage struggle. Randol explained that today he was looking for a part to play and came upon this battery of 20-pounder Parrotts whose German gunners had precipitously left the field at Glendale. Their officers apparently absent, Randol appropriated the battery, aided by his lieutenant who spoke a little “Dutch,” took it to the front, and administered a lesson in both gunnery and leadership.

Darius Couch had his hands full fending off some of the heaviest Rebel attacks, and he turned to Porter for help. Porter appealed to Sumner, but met reluctance—Sumner, as usual, expected to be attacked any moment, no matter that he was more than a mile from the fighting. Sam Heintzelman was willing: “By God! If Porter asks for help, he wants it, and I’ll send him a brigade.” He ordered up Sickles’s brigade, plus a battery. Thus prodded, Sumner sent forward Meagher’s Irish Brigade, and soon the front was stabilized. Couch reported pridefully, “Sumner, Kearny and Sedgwick gave me no little praise for the successes I achieved on this day.” Hunt was equally prideful: General McClellan was “in every way and in all respects thoroughly satisfied with me and my work.”

Phil Kearny acted his usual ungovernable self. That afternoon, after Heintzelman posted one of the Third Corps batteries, Kearny came along and shifted it elsewhere. Heintzelman returned and demanded to know who had moved the guns. Lieutenant Charles Haydon took up the story: “On being told he rode brim full of wrath for Gen. K. ‘You countermand another order of mine & I will have you arrested, Sir’ said H. ‘Arrest my ass, God damn you,’ said Kearny and rode off. . . . Heintzelman looked after him very earnestly for near a minute. A faint smile came over his features & he himself turned around & rode slowly off leaving the battery where he found it.”

“The struggle continued until nine o’clock p.m., when the rebels withdrew,” wrote artillerist Alexander Webb. “The author, an eye-witness, can assert that never for one instant was the Union line broken or their guns in danger.” At 6:10 p.m. Porter had reported to McClellan, “The enemy has renewed the contest vigorously—but I look for success again.” By 9:30 he declared victory: “After a hard fight for nearly four hours against immense odds, we have driven the enemy beyond the battle field. . . .” If reinforced, if the men were provisioned and their ammunition replenished, “we will hold our own and advance if you wish.” His victorious men “can only regret the necessity which will compel a withdrawal.”

The general commanding, however, had already issued orders for the final leg of the retreat, to Harrison’s Landing. Porter’s report of a complete victory did not move him to reconsider. He explained to Lincoln: “I have not yielded an inch of ground unnecessarily but have retired to prevent the superior force of the Enemy from cutting me off—and to take a different base of operations.”

McClellan’s lieutenants were dismayed (or worse) by his order to continue the retreat. Darius Couch, who had smothered the assaults on Malvern Hill, recalled his “great surprise” at leaving a victorious field, and his bitterness at abandoning “many gallant men desperately wounded.” For staff man William Biddle, “the idea of stealing away in the night from such a position, after such a victory, was simply galling.” Israel Richardson observed that “if anything can try the patience and courage of troops,” it was fighting all day every day, then falling back every night. Phil Kearny was livid. To fellow officers he declaimed, “I, Philip Kearny, an old soldier, enter my solemn protest against this order to retreat. We ought, instead of retreating, to follow up the enemy and take Richmond. . . . I say to you all, such an order can only be prompted by cowardice or treason!”

In the early hours of July 2 Fitz John Porter and Baldy Smith found time for a conversation as their commands trudged toward Harrison’s Landing. Porter described the decisiveness of the victory at Malvern Hill, and said he had spent the night trying to persuade McClellan to change his mind and move against Richmond at daylight. Knowing Porter to be McClellan’s closest confidant, and knowing Porter’s own native caution, Smith was fully persuaded just how ill-judged was McClellan’s decision. When he reached Harrison’s Landing, he wrote his wife “saying I had arrived safely but that General McClellan was not the man to lead our armies to victory.”

Malvern Hill was indeed a decisive victory. Confederate losses on July 1 came to 5,650. The Federal loss was just 3,007, and some 800 of those were stragglers picked up by the enemy during the retreat on July 2. Moreover, in its amphitheater-like setting Malvern was a highly visible victory, for all to witness (all but General McClellan) and a tonic to the fighting men of the battered Army of the Potomac.

A retreat already ugly turned uglier when it began to rain, a downpour that lasted twenty-four hours. “The retreat was a regular stampede, each man going off on his own hook, guns in the road at full gallop, teams on one side in the fields, infantry on the other in the woods,” wrote Richard Auchmuty. “At daybreak came rain in torrents, and the ground was ankle deep in mud.” To Francis Barlow “it was more like a rout than a ‘strategical movement.’” Joe Hooker called it “the retreat of a whipped army. We retreated like a passel of sheep. . . .” John Peck’s unbloodied Fourth Corps division acted as rear guard, hurrying along the stragglers and untangling massive tie-ups among the trains. The stunned and wounded Army of Northern Virginia offered no pursuit.

No one excelled George McClellan at inspiriting troops. At Harrison’s Landing on July 4, Independence Day, he raised spirits with an address to the army. Like an alchemist he sought to transmute leaden reality into silvery triumph. “Attacked by vastly superior forces, and without hope of reinforcements, you have succeeded in changing your base of operations by a flank movement, always regarded as the most hazardous of military expedients. You have saved all your material, all your trains, and all your guns, except a few lost in battle. . . .” (The Potomac army in the Seven Days lost war matériel beyond counting, wagons by the hundreds, and forty guns in battle.) “Your conduct ranks you among the celebrated armies of history. . . .”

The address played well to the rank and file, which needed assurance that their stout fighting and their costly sacrifices over the past bloody week had not been wasted. What had seemed a retreat was now officially a change of base. “All our banners were flung to wind,” Charles Haydon told his journal. “A national salute was fired. The music played most gloriously. Gen. McClellan came around to see us & we all cheered most heartily for country, cause & leader.”

If Charles Haydon spoke for a majority of the troops, fellow Third Corps soldier Felix Brannigan represented a vocal and growing minority. The papers speak of the “splendid strategy of McClellan,” Brannigan wrote. “I think he was forced to it. Anyhow, he gets too much credit for what other people do. McClellan kept at a respectable distance in action, but the real saviours of the army were Heintzelman, Kearny, Hooker, Richardson, and their subordinate generals. They were here, there, and everywhere . . . mixing in the thickest of the fray. Heintzelman with his old cloak and battered hat, and the one-armed Kearny, were particularly conspicuous.” Henry Ropes, Sedgwick’s division, thought “a great deal of faith in McClellan is gone, and I fear will not return.”

In the officer corps faith in McClellan was clearly shaken. “You have no idea of the imbecility of management both in action & out of it,” Francis Barlow wrote home. “McClellan issues flaming addresses though everyone in the army knows he was outwitted.” Everything he saw and heard, said Barlow, “more & more convinces me that McClellan has little military genius & that he is not a proper man to command this Army. I think the Division Genls & about everybody else here have lost confidence in him.” Barlow’s remark on discontent among the generals of division was perceptive. Of those who expressed opinions, Kearny, Hooker, and Baldy Smith were McClellan’s more outspoken critics. Richardson and Couch regarded the final retreat, to Harrison’s Landing, as a mistake. Henry Slocum wrote his wife, “I have allowed matters connected with our movements here to worry me until I came near being sick.”

The five corps commanders were more discreet. Edwin Sumner’s narrow vision focused more on obeying orders than on reasoning why. Still, he favored holding Malvern Hill “if my opinion had been asked about it.” Sam Heintzelman, highly critical of McClellan’s repeated failures to lead, welcomed his own chances at independent command. Erasmus Keyes was so isolated by McClellan that he scarcely witnessed a shot fired. William Franklin, while a McClellan loyalist, was quietly unhappy with events. “I wept at the mismanagement and waste, and I know other officers who did so too,” he told his wife. While Fitz John Porter argued against the final move to Harrison’s Landing, he remained a McClellan partisan; he cast all the blame on Washington. Samuel Barlow warned McClellan of “the jealousy of your own Generals, including Sumner, Heintzelman, Kearny & I fear even of Baldy Smith!”

Harrison’s Landing was a secure base, with swampy creeks forming its flanks and gunboats as watchdogs. But as an encampment it was a miserable place. Kearny complained that “we are completely boxed up, like herrings.” Into some four square miles of lowland were crowded 90,000 men, 25,000 horses and mules, 2,000 beef cattle, almost 3,500 wagons and ambulances, and 289 guns. The water was bad, flies were a constant plague upon man and beast, and it was stiflingly hot and humid. The army’s sick list at its peak reached 22 percent.

Malvern Hill was a superior base in every respect—stronger defensively, certainly healthier, and (should it come to that) a proper starting point for a renewed offensive against Richmond. By McClellan’s account, the navy was the reason he did not exercise the victor’s claim to the Malvern battlefield. Gunboats could guarantee the army’s supply line only as far as Harrison’s Landing, where the James was wide. Above that it narrowed at Haxall’s Landing, and McClellan imagined harassing fire from the south bank.

McClellan might have secured Haxall’s himself—and doubled his threat to Richmond—by seizing the south bank of the river with his own or with fresh troops. Ideal for that was Ambrose Burnside’s command just then landing at Fort Monroe from North Carolina. But that option did not occur to the Young Napoleon. His only thought now was securing his army from the ravening enemy host.