The last great land-based crusade against the Ottoman Empire, which ended in the defeat of a Balkan Christian coalition by the Turks near the city of Varna (in mod. Bulgaria).

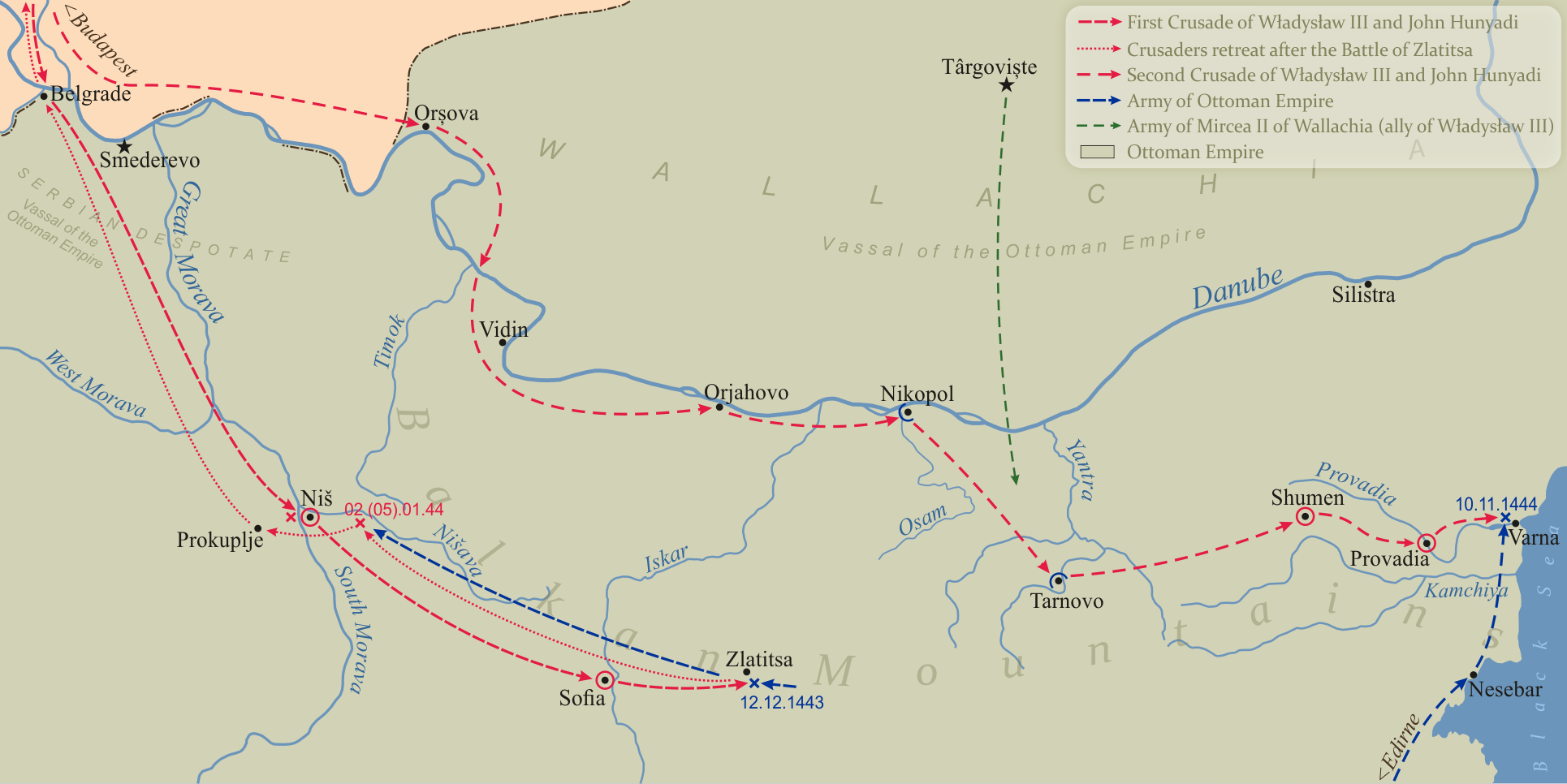

The Varna Crusade came about in response to Ottoman advances in the Balkans, notably the occupation of Serbia (1439) and the siege of Belgrade (1440). In 1443, for the first time after the disastrous Nikopolis Crusade (1396), Hungary initiated an ambitious offensive campaign against the Ottoman Empire, encouraged by Pope Eugenius IV and his legate Cardinal Giuliano Cesarini. A Hungarian army of some 35,000 troops, led by the famous general John Hunyadi (Hung. Hunyadi Janos), was accompanied by Cesarini, the Serbian despot George Brankovi’c, and King Vladislav I (king of Poland as Wladyslaw III), who had been elected as king of Hungary in expectation of significant Polish support against the Turks. The army left Buda on 22 July 1443, crossed the Serbian border by mid-October, and occupied Sofia by December. Having gained some other minor victories, it returned home in January after learning that Sultan Murad II had crossed the Bosporus, and celebrated a spectacular triumphal march in Buda.

Faced with a revolt by the Karamanids in Anatolia in spring 1444, the sultan was unwilling to face war on two fronts, and offered favorable peace conditions to Hungary: peace for ten years, the surrender of Serbia and Bosnia, the liberation of the sons of Brankovi’c, and 100,000 gold florins. The extravagant peace terms confused the political parties in Hungary; before the sultan’s offer in April the Hungarian diet had voted for war, and the king had taken a solemn oath to carry it out. The war was also supported by the legate Cesarini, who envisaged the union of the Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox churches and the relief of Constantinople, and by the Polish court party in Buda, though it was rejected by Poland.

The period between April and September is very controversial, and has been clarified only recently. Despot Brankovi’c accepted the sultan’s conditions, and offered John Hunyadi his own immense possessions in Hungary in exchange for his support of a future peace treaty. Hunyadi seems to have accepted Brankovi’c’s offer, which meant that Hungary was preparing for war and negotiating peace terms at the same time. A tentative peace treaty was concluded by the Hungarians at Adrianople (mod. Edirne, Turkey) on 15 June, and the sultan left Europe on 12 July to lead his troops against his adversaries in Anatolia. In this precarious situation, the Hungarians tried to win both peace and war. On 4 August at Szeged, King Vladislav declared invalid any former or future treaties made with the infidels, with the approval of Cesarini. Meanwhile the Hungarian-Ottoman peace treaty was ratified on 15 August in Varad (mod. Oradea, Romania) by the king, John Hunyadi, and Brankovi’c, only a few miles from the forward outposts of the royal army. A papal-Venetian fleet sailed to blockade the Dardanelles, but the Hungarian-Ottoman diplomatic activity disturbed the European Christian coalition and the efficacy of the blockade, causing delay and depriving the campaign of the necessary surprise effect. The unity of the coalition was now in tatters. Despot Brankovi’c was satisfied to have at least regained northern Serbia together with its capital (22 August); he not only failed to join the coming war, but even tried to hinder it.

The Christian coalition army amounted to some 20,000 men, considerably fewer than the previous year. It consisted mostly of Hungarians, along with Polish and Bohemian mercenaries and some 2,000-3,000 Wallachian light cavalry led by Vlad Dracul; the absence of any Serbian and Albanian auxiliary troops should have been a warning signal. The army left Orflova on 20 September, intending to strike at the Ottoman capital of Adrianople. The Christians marched along the Danube route via Vidin (26 September) and Nikopolis (16 October), and turned southeast via Novi Pazar and Shumen, capturing and plundering all these cities. Due to bad reconnaissance, they did not know that the sultan had already crossed the Bosporus with an overwhelming (perhaps double) numerical superiority.

The Christians met the sultan at the city of Varna on 9 November, on terrain unfavorable for them, between the lake of Devna and the sea coast. Despite John Hunyadi’s military talent, the Christians were defeated as a result of poor cooperation among the multinational coalition forces. Hunyadi initially gained the upper hand on both wings by the overwhelming attack of his heavy cavalry. The sultan considered a retreat, but at the next decisive moment King Vladislav attacked the Turkish elite janissary units with his Polish troops. This ruined the Christian tactics, and resulted in the death of the king and the papal legate. The Christian battle order dissolved, and the cavalry left in panic-stricken flight, including John Hunyadi, who escaped to Wallachia. Both sides suffered heavy losses, above all among the Christian infantry units that attempted to defend their camp behind wagons in a manner similar to that of the Hussite troops of Bohemia.

The Hungarian and papal war parties had been correct in their assessment that 1444 presented the best opportunity in a long time to wear down Ottoman power by force of arms. This crusade, however, proved to be the last spectacular failure of traditional crusading strategy: sweeping the Ottomans out of Europe in a single campaign, in the absence of political unity among the fragmented and partly conquered Balkan states, proved to be impossible, and the Christians were unable to make full use of the favorable peace conditions. Much more could have been achieved by accepting the peace terms than by launching a campaign into an unstable region. As had been done by King Sigismund after the defeat of the Nikopolis Crusade in 1396, the Hungarian kings again adopted a deliberate defensive strategy (particularly under King Matthias Corvinus, son of John Hunyadi) up to the final collapse of the Hungarian defense system in 1521 and of the medieval kingdom of Hungary itself in 1526.

Bibliography Babinger, Franz, “Von Amurath zu Amurath. Vor- und Nachspiel der Schlacht bei Varna 1444,” Oriens 3 (1950), 229-265. Cvetkova, Bistra, La Bataille mémorable des peuples: Le sud-est européen et la conquete ottomane (Sofia: Sofia Press, 1971). Engel, Pal, “Janos Hunyadi: The Decisive Years of his Career, 1440-1444,” in From Hunyadi to Rakoczi: War and Society in Medieval and Early Modern Hungary, ed. Janos M. Bak and Béla K. Kiraly (Boulder, CO: Atlantic, 1982), pp. 103-123. —, “Janos Hunyadi and the Peace of Szeged,” Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 47 (1994), 241-257. Halecki, Oscar, The Crusade of Varna: A Discussion of Controversial Problems (New York: Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences in America, 1943). Imber, Colin, The Crusade of Varna, 1443-45 (Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2006). Papp, Sandor, “Der ungarisch-türkische Friedensvertrag im Jahre 1444,” Chronica: Annual of the Institute of History, University of Szeged 1 (2001), 67-78. Setton, Kenneth M., The Papacy and the Levant, 1204-1571, vol. 2: The Fifteenth Century (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1978).

John Hunyadi and the Late Crusade: A Transylvanian Warlord against the Crescent (Retinue to Regiment) Paperback – January 19, 2020 by Andrei Pogăciaș (Author)

The book aims to present the life and military exploits of one of the biggest commanders in European medieval history.

The chapters will present his life, the realities of Hungarian and Transylvanian politics, relations with the Ottomans and other states, military strategy and tactics in the battles against the Turk – the defensive battles of 1442, The Long Campaign 1443-44, Varna 1444, Kosovo 1448, Belgrade 1456 and other smaller battles.

There will be a presentation of the structure of Hungarian and Transylvanian armies and the tactics they used.