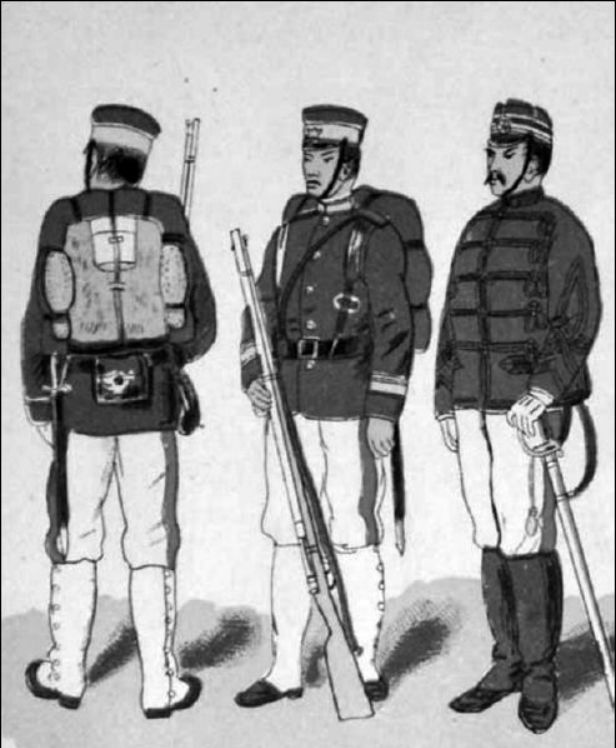

Soldiers of the Japanese army. From the left: private, sergeant and captain.

Comparative strength of belligerents and their war plans

Japan

The modern Japanese army originated from the Imperial Guard, created in April 1871 in the strength of nine infantry battalions, two cavalry units and four artillery brigades. These were the first regular Japanese European-style units. Soon thereafter a draft of the military reform was prepared, which was approved by Imperial edict in January 1873. By its power, universal conscription was introduced and all men of a particular age were obliged to serve. Along with the abolition of class differences, this was a serious blow to the samurai class, for which military service had been an honourable distinction which decided their social and material situation. The reforms inevitably caused dissatisfaction in that group, which found its outlet in a few armed riots of the ‘unemployed’ samurai, including the famous Saigo Takamori’s rebellion of 1877. However, all these were swiftly put down and the samurai, convinced of the European-style troops’ effectiveness, were quick to join the ranks of the army, which allowed them to regain their former prestige. Consequently, in a relatively short time, Japan managed to create a valiant and well-trained army based on German standards. Its officer corps was mainly composed of former samurais, who introduced old military traditions. That blend of tradition, modern organisation and armament gave excellent results – an army that was equal to European armed forces in every respect.

On the eve of the outbreak of the war with China, all men between 17 and 40 years old were under conscription, but only those who turned 20 could be drafted (younger ones, who turned 17, could volunteer). Following the period of active military service (gen-eki), which lasted for three years, the soldiers became the 1st Reserve (yobi), than the 2nd Reserve (kobi). Young and able-bodied men, who did not have basic military training became 3rd Reserve (hoju) right away and so did those conscripts who had not fully met the physical requirements of the service. All soldiers who served their term joined the ranks of the territorial militia (kokumin). In case of war, the 1st Reserve (yobi) were to be enlisted in the first instance. They were intended to fill in the ranks of regular troops. Next to enlist were the kobi reserve, who were to further fill in the ranks of line units or to be formed into new ones. The hoju reserve members were to be enlisted only in exceptional circumstances. Territorial militia would only be called to arms in case of immediate danger of enemy invasion.

The country was divided into six military districts, each being a recruitment base for a two-brigade infantry division of approximately 18,600 troops (including 1/3 of rearguard units) and 36 artillery guns in times of war. There was also an Imperial Guard division with recruits from all districts. This was also composed of two brigades, but they were made of two, not three battalion regiments. Therefore, its numerical strength after mobilisation was 12,500 troops (including rear echelon units) and only 24 artillery guns. In addition, there were fortress troops (approximately six battalions), the so-called ‘Colonial Corps’ stationed on Hokkaido and the Ryukyu Islands (about 4,000 troops) and a battalion of military police in each of the districts. In peacetime these units had a total of fewer than 70,000 men, while after mobilisation the numbers rose to over 220,000. Moreover, the army still had a trained reserve. Following the mobilisation of first line divisions, those reserves were to be formed into reserve brigades (four battalions, a cavalry unit, a company of engineers, an artillery battery and rear echelon units each), which in the first instance were to serve as recruiting base for ‘their’ front divisions. They could also perform secondary combat operations. If necessary they could be developed into full divisions, i.e. a total of 24 territorial force regiments. However, formation of these units was hindered by the lack of sufficient volume of equipment, mainly uniforms.

The main weapon of a Japanese soldier was the 8mm Murata Type 18 breech-loading rifle. The improved five-shot Type 22 was just being introduced and in 1894, only the Imperial Guard and 4th Division were equipped with rifles of that pattern. The division artillery consisted of 75mm field guns and mountain pieces with muzzles made of hardened bronze manufactured at Osaka. That equipment, based on Krupp designs adapted by the Italians at the beginning of the 1880s, could hardly be described as modern in 1894, although in general, it still matched contemporary battlefield requirements.

Japanese troop training promoted offensive spirit and special attention was paid to forming resilience and strength in battle. In combination with systematic training and strict discipline it produced good results and consequently, the combat effectiveness of Japanese troops was high. The only weak point in the Japanese army was the logistics services, which were not very efficient. This could be observed especially during the Manchurian and Korean campaigns. Despite the fact that the armament of the Imperial troops was not as modern as some of latest patterns used by some of the Chinese units, their combat effectiveness was incomparably higher than that of the enemy, being equal to European armies.

The Japanese cruiser Itsukushima. Units of this class were built specifically to face the Chinese battleships – thus, they were armed with a huge single 320mm gun, whose projectiles were able to penetrate the armour of Chinese warships. Despite the fact that the design failed, cruisers of that class constituted the core of the Japanese navy during the war with China.

The Japanese navy came into being along with the Meiji Restoration in 1868. The isolationist policy adopted at the beginning of the 17th century stopped the development of the Japanese naval tradition. Consequently, until the 1860s the naval forces were practically non-existent. Their rebirth started only after the ‘opening of Japan’ in the 1850s. However, there was no centralised naval policy and individual clan leaders (daimyos) had their own armed forces including navies. That situation came to an end in 1869 with the Meiji Restoration, which dismantled the bakufu system. As the result of those events, the imperial government also took over all the warships which belonged to the shogun and placed them under the control of the Ministry of War (Hoyobusho), which had been created in August 1869. However, over 85 per cent of all vessels were still under control of daimyos.

Such a weak and poorly organised navy could not be considered an effective force, which was clearly demonstrated during the Enomoto Rebellion. The rising was not successfully put down until mid 1869. Already in March of the same year, on the rising tide of patriotic elation, the most powerful daimyos of Satsuma, Choshu, Tosa and Hizen clans renounced their feudal right and offered to hand over their estates to the emperor. The court accepted their offer in June, thus starting the process known later as hansen-hokan (return of the registers). Within the following six weeks, rights were renounced by a further 118 daimyos and by the end of August 1869, only the last 17 (of a total of 276) had not done so. This event had a significant meaning for the future fate of the Japanese navy, since along with their rights, land and fixed property, daimyos also started to hand over their movables including the warships that had been under their control so far. Their takeover by central authorities was a gradual process which lasted until the beginning of 1871. Control over those warships was taken by the Ministry of War, which had an autonomous naval section since February 1871. In June 1871, the existing Ministry of War was divided into the Ministry of the Army (Rikugunsho; unofficially still known as the Ministry of War) and the Ministry of the Navy (Kaigunsho).

The new ministry took control over all warships, which were a mix of types and classes of different characteristics and in various state of repair. Guided, on one hand, by economic policy and on the other trying to eliminate units of dubious combat effectiveness, out of over 100 warships and transports, only 19 vessels, of a total of 14,610 tons and complements of almost 1,600 men, remained in service. Moreover, the shipyards Ishikawajima and the naval shipyard at Yokosuka (so far remaining under the control of the Ministry of Public Works) came under control of the Ministry of the Navy and so did the Tokyo Naval Academy, established in 1873.

The beginnings of the Japanese navy were not easy since circumstances marginalised its role. Suffice it to say that in the years 1868 to 1872 there were about 160 peasant revolts or rebellions, which had to be put down mainly by land troops. Still later, there were at least three significant former samurai rebellions including the famous Saigo Takamori’s Rebellion in 1877. Again, the navy’s role in putting them down was insignificant. Thus, the development of the army became the priority of the Japanese government in the first half of the 1870s and that inevitably affected the condition of the navy. Thus, when in 1873, Minister of the Navy Katsu Kaishu put forward the first in Japanese history naval build-up programme which would provide for construction of 104 vessels (26 of metal, 14 large and 32 smaller ones of mixed construction plus 32 transports and auxiliary vessels) within 18 years for the sum of 24,170 thousand yen, the plan was rejected by the government for financial reasons.

The situation changed considerably following the Japanese intervention on Taiwan, lasting from May to October 1874, which made Japanese authorities realise the need for a strong navy. Consequently, still in 1874, a decision was made to order three modern warships (including one battleship) from Great Britain, which would significantly strengthen the imperial navy. All the warships, built for a total of three million yen, were delivered in 1878. Until the mid-1880s, a further six medium size units (in fact there were five warships and an imperial yacht) and two training sailing vessels were built by native shipyards. Additionally, four torpedo boats were purchased abroad. However, these were all short-term measures which did not ensure the appropriate development of the navy in the long run.

Meanwhile, the financial situation of the country began to improve. This was not so much due to increased income, but to settlement of some legal-financial and administrative issues. Moreover, the introduction of the cadastre brought regular revenues, although not high enough to cover every need. All that allowed for real planning of budgetary expenditures, including military ones. Consequently, in 1881, Minister of the Navy Kawamura Sumiyoshi (who had held the position since 1878), put forward another naval build-up programme which would provide for construction of a total of 60 vessels within 20 years (at three units a year) for 40 million yen. Although it was not endorsed by the government, the next year brought the approval of an eight-year programme which would provide for the construction of a total of 48 vessels and modern naval bases at Kure and Sasebo (apart from the already existing base at Yokosuka) for a total of 26,670,000 yen. Its purpose was the creation of a navy, which would provide effective protection of the Japanese islands and at the same time be capable of limited-scale offensive operations, especially against Japan’s largest potential enemy – China. Guided by its economy policy, the Ministry of the Navy adopted the French concept of the ‘Young School’ (Jeune École), which advocated the use of torpedo forces for coastal defence and cruisers for offensive operations against enemy communication lines. The adoption of such a solution was a result of a compromise between the need to guarantee the appropriate potential of the navy in case of the war with China and the ability to undertake effective operations in case of conflict with a European power.

To provide suitable funds for the programme (as well as other military spending), in 1882, the Japanese government introduced excise duty on sake (Japanese rice vodka), soya and tobacco, which annually generated income of approximately 7.5 million yen. An increase in the fiscal burden on society provided additional income, and therefore naval spending rose from 3.4 million yen in the financial year 1882/1883 (the first budget year of the implementation of the programme) to 9.5 million yen in the financial year 1891/1892. It enabled for full realisation of the 1882 programme, which after the introduction of some modifications, saw the completion of 22 large and medium size warships (nine cruisers, six small cruisers, two torpedo gunboats and five gunboats), two training vessels and 18 torpedo boats, as well as the aforementioned naval bases at Kure and Sasebo. These warships were to face the Peiyang Fleet in the coming war.

The emperor was the commander-in-chief of the Japanese armed forces, both the army and the navy. The Ministry of the Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy General Staff were also directly subordinate to him. The former body was responsible for all structural, technical and personnel matters, while the latter was responsible for those directly connected with the organisation of combat operations and maintaining of combat readiness. At the moment of the outbreak of the war with China, the post of the Minister of the Navy had been held since 1893, by Vice-Admiral Saigo Tsugumichi30. Vice-Admiral Kabayama Sukenori, an experienced officer, able and energetic, albeit sometimes thought a bit too impulsive, had been the Chief of General Staff since July 1894. Shortly after the commencement of military operations, a High Command was created in Tokyo, which, apart from the emperor, gathered the foremost officers of the army and the navy, and was responsible for important strategic decisions made during the war. Due to its unsatisfactory location, since most of the mobilised troops were concentrated at Hiroshima and dispatched to the front lines from the harbour of Ujina located nearby, the High Command was transferred to Hiroshima in mid-September.

The entire coast of Japan was divided into five naval districts based at Yokosuka (District I), Kure (District II), Sasebo (District III), Maizuru (District IV) and Muroran (District V). Since in 1894, the organisation of the fourth and fifth had not yet been finished, the territory of District IV was placed temporarily under the management of the Kure authorities and partially those at Yokosuka, while District V was only under the control of the latter authority.

In peacetime, warships of the Japanese navy were divided among three main naval bases at Yokosuka, Kure and Sasebo, interchangeably performing active, guard and training duties or remaining as a reserve. Following mobilisation, the navy would be composed of five divisions of seagoing warships and three flotillas of torpedo boats (a fourth was being formed). Obsolete units of little combat effectiveness were not mobilised. During peacetime, at the end of 1893, there were 14,850 officers and seamen in the service, but during the war the number increased to over 20,000 men.

A relatively large merchant navy, which at the beginning of 1894 had 288 steamers of a total of 174,000 GRT, was an excellent complement to the Japanese navy. Sixty-six of these vessels, of a total of 135,755 GRT, belonged to Nippon Yusen Kaisha, the shipowner which received national treasury subsidies to maintain the vessels which could be used by the navy in case of war. Thus, the navy could call on a sufficient number of auxiliaries and transports.

During the war with China, the naval base at Sasebo played the most important role. Apart from Sasebo, harbours at Hiroshima (Ujina), Yokohama, Kobe and Nagasaki – mainly for loading troop and supplies – would also be used. Muira Bay in the Tsushima Archipelago would be used as a temporary base and later also some Korean harbours and anchorages. Naval bases at Kure and Sasebo, as well as the entrance to the Tokyo Bay were heavily fortified and equipped with considerable numbers of 120mm to 280mm coastal artillery guns.

The Japanese Navy was under the immediate command of Admiral Ito Yuko, who was not a brilliant commander, but undoubtedly experienced and well-prepared for his duty. He was by nature cautious and not willing to take any unnecessary risks, but was at the same time a skillful tactician, persistent and not easily discouraged. Japanese crews were also well prepared for war – both officers and ordinary seamen were well-trained, and their morale was excellent. Only the rules of officer promotion and appointment to command posts could raise some objections. Although class divisions were abolished in 1871, samurai background could definitely make a career easier. Clan connections were also still important – following 1872, the Satsuma clan had a majority in the navy and its members constituted most (though not all) high ranking naval officers. Essentially, the aforementioned phenomenon did not violate internal discipline of the navy and with minimum essential requirements for a commanding post in effect, it did not have significant impact on the level of training of the officer corps, which could be considered good.

Japanese navy tactics were based on combat regulations of 1892. They assumed that Japanese warships would enter combat in line-ahead (in four-warship divisions) with the flag-ship in the lead. At times when signals could only be transmitted visually (by signal flags, light or semaphore signals), this formation was supposed to facilitate commanding and manoeuvring of the entire force in face of the enemy. The role of speed and manoeuvre was very important, as they would allow for optimal utilisation of the existing combat potential. As a matter of fact, the Japanese performed tactical experiments almost from the beginning of the war (mainly thanks to Rear Admiral Tsuboi), developing the rule of dividing forces in battle into the main force and a fast manoeuvring unit, which, while operating separately on the battlefield, would fight in concert, giving the advantage over a homogenous enemy force (advantages in speed of manoeuvring unit would allow the force to attack weak points of the enemy formation or absorb his attention to facilitate operations of the main force).

To sum up, the combat effectiveness of the Japanese navy was high, lowered only by the lack of modern battleships, which on the other hand, the Chinese were in possession of. Admittedly, a temporary naval build-up programme passed in 1892, which provided for the construction of two battleships, three cruisers and one small cruiser, constituted a clear departure from the ideas of the ‘Jeune École’ but it was not completed before the outbreak of the war with China. Consequently, in the coming war, the naval forces of China and Japan could have been balanced – better training and more modern armament on the Japanese side was counterbalanced by large and relatively modern battleships on the Chinese side.

Japanese Plans

Japan, on entering the war, had a clearly specified plan of action, whose main military objectives were the capture of Korea and driving the Chinese troops behind the Yalu River. It would be executed in three phases.

The first phase would be further divided into three stages: the Japanese navy would prevent the delivery of reinforcements for the Chinese corps under General Yeh at Asan. Then, General Oshima’s brigade would defeat Yeh’s force, and finally take Seoul. The second stage would comprise the prompt redeployment of the I Army forces to Korea, while the third stage would be defeating the Chinese troops concentrated at Phyongyang and driving them behind the Yalu River. Accomplishment of the third stage would end in the conquest of the entire Korean territory.

Japanese victory in Korea would be largely dependent on maintaining control of their sea communication lines in order to freely deliver supplies and reinforcements to their troops fighting on the mainland, the second phase of operations would be for the Japanese navy to secure the control of the sea. It was anticipated that this would be achieved in a decisive naval battle, but the timing of that phase was fluid. It depended on the actions of the enemy, but the fastest possible capture of Korea was a priority. Only then would energetic operations against enemy naval bases commence, in order to annihilate its navy (or any forces which survived the expected decisive naval battle). The second phase would end with achieving total control of the sea and annihilation of the enemy’s naval forces.

If, following the loss of Korea and control of the seas, the Chinese still possessed the will to fight, the Japanese anticipated a third phase of a series of offensive operations, both on land in Manchuria and, exercising full control of the sea, also against selected coastal targets, which had the potential to inflict heavy losses and force the authorities in Peking to sign a peace treaty on Japanese conditions.

Thus, the Japanese war plan was distinctly offensive in nature and largely based on the principles of the classic naval doctrines of Mahan and Colomb. Its characteristic feature was that redeployment of troops to Korea was not dependent on seizure of the absolute control of the sea. Logically speaking, taking control of Korea should have been dependent on control of the sea. Every other combination, even taking into consideration passivity and ineptitude within the Chinese high command, attracted a serious risk of a breach in the communication lines between the troops fighting in Korean and the homeland. Should this be fulfilled, the worst-case scenario would mean a catastrophe of unimaginable consequences, even after initial successes. However, the Japanese deliberately took that risk, taking into consideration the country’s economic potential. Japan simply had no means of waging a long-lasting war with wealthy China. War had to be swift and successful. Therefore, a more risky military plan was adopted to avoid lengthy military actions, which would be destructive for the Japanese economy. However, it should be emphasised that the risk taken was within acceptable limits and with certain discipline of operations and strategic initiative, the Japanese plan nevertheless had a good chance to grant a significant degree of success – especially if the overall advantages in the quality of Japan’s forces were taken into consideration.