Effect of the loss of the Atlantic bases

“… 15.9.44. Now that the French Atlantic ports are no longer in our possession, U-boat operations will be continued from Norway. A few Home ports will also be used, since the Norwegian bases have insufficient accommodation, and operational possibilities will thus be limited. The Type IXC boats will no longer be able to operate either in the Caribbean or on the Gold Coast without refuelling, and will therefore be obliged to concentrate mainly on the US coast, the Newfoundland area and also the St Lawrence, which is again accessible to schnorkel boats. As a rule we shall be unable to use the Type VIIC boats in the Channel, since the passage takes so long that they would be unlikely to arrive in a fit state to operate under such difficult conditions; the only other areas remaining to them are the Moray Firth, the Minch and the North Channel in British coastal waters, and Reykjavik.

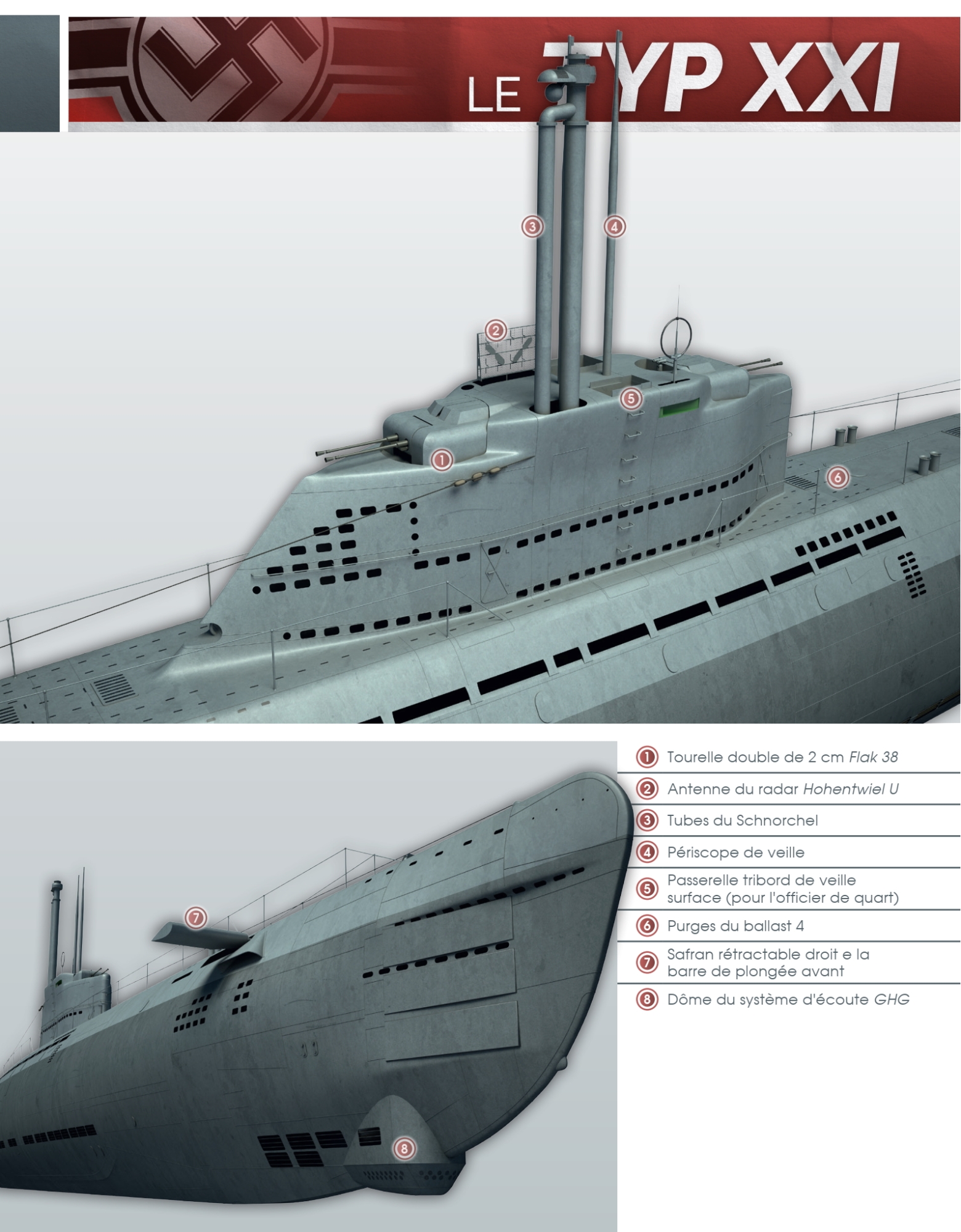

“It must be assumed that the enemy will concentrate his A/S forces off Norway, and in the Atlantic passage, North Sea and Baltic approaches. Theoretically, he can build up such heavy concentration in these regions that the old-type boats, which need to schnorkel fairly often, are bound to be located sooner or later and subjected to a concerted attack. Hence, if it were necessary to continue the campaign with these old types, the loss of the Atlantic bases would prove to be grave and decisive; but the new Type XXI boats, by virtue of their very great endurance, high submerged speed and deep diving capability, should be able to thrust their way through the enemy A/S concentrations to operate successfully both in the North Atlantic and in remote areas…”.

This brief statement outlined the U-boat situation as FO U-boats saw it at the beginning of October 1944, irrespective of the general course of the war; and in order to understand his apparent confidence in the future success of the new-type boats, it would be well at this point, to examine the provisions of the 1943 Fleet Building Programme, in so far as they affected the U-boat.

The U-boat building programme taxes German productive capacity

A major barrier to successful implementation of the overall U-boat building programme lay in a dual requirement for both rapid achievement of mass production of the new boats and maintenance of the rate of delivery of the older types, which necessitated provision of double the quantity of materials and manufacturing capacity over a transition period of from six to eight months. One of the prime essentials was to step up the production of U-boat batteries, and to achieve this in the short time available before the new boats began to arrive from the builders was the Armaments Ministry’s most difficult task; no plant for the manufacture of batteries existed in Germany itself, so it was necessary to produce the requisite machinery and equipment for this at the expense of current contracts, except those concerned with aircraft production, which had absolute priority. An additional problem, which at first appeared insoluble, was posed by the sheer quantity of lead and rubber needed for the batteries; but this difficulty was later overcome.

The new boats had also to be equipped with very powerful electric motors and a large number of other electrical fittings, such as cruising motors, trimming and bilge pumps, echo-ranging gear, underwater listening apparatus, radio and radar sets and radar search receivers, production of which engaged a considerable part of the whole German electrical industry and was only made possible by severe curtailment of such essential work as power-station and locomotive construction.

The provision of high-grade steel plate for the pressure hulls posed another difficult problem, for this commodity constituted the worst bottleneck in the whole of the steel industry and, since the old-type boats had still to be built and the new types required even more, demand for steel plate from the autumn of 1943 was three and a half times as great as the allocation hitherto. Furthermore, because of a heavy requirement for the repair of bomb damage to warships and local installations, the dockyards, already burdened with the expanded naval building programme, were now unable to cope with the shaping of pressure-hull sections, which had therefore to be delivered ready rolled.

The Chairman of the Central Shipbuilding Committee, Herr Merker, had taken on a difficult task. Considerable risk was involved in mass-producing a fundamentally new type of U-boat without trials, for if the boat proved to be a failure, the prodigious efforts of German industry would have been in vain and material allocated for the construction of 180 to 200 U-boats would have become so much scrap. Just as great a risk was involved in the introduction of prefabrication and mass-production methods into general shipbuilding; both methods were being applied for the first time to craft of considerable size under severe wartime conditions and against the advice of many experts, while those responsible were beset by the worry of completing the task at the earliest possible date. Nevertheless, contracts were placed with German yards for 360 Type XXI and 118 Type XXIII, and in the Mediterranean ports for 90 Type XXIII U-boats.

Prefabrication and mass production

The hull of the Type XXI U-boat was made up of eight separate sections – one section to a compartment – and these sections were constructed in 13 different yards, which allowed duplication and ensured that if a number of sections were destroyed in one yard a corresponding number of U-boats would not be lost. Nevertheless, the safety of the section-building and U-boat assembly yards was a matter of much concern, and in 1944 efforts were made to provide them all with bunker protection, a step already in hand at Hamburg-Finkenwerder and Bremen-Farge, with a few others being improvised elsewhere. The situation would have been less critical if section building could have been moved inland; but this was impossible as, owing to their size, the sections could only be transported to the assembly yards by water.

The actual building process was roughly as follows. A section-building yard was supplied first with, say, 40 similar part-sections of section 1 – the stern section of the boat – and delivery of the remaining part-sections was then timed to ensure the completion of the sections in sequence; thus, at any given time there would be 40 sections in progressive stages of assembly. The larger part-sections were machined and prepared for assembly on the actual site, while the smaller ones passed through the machine shops on the conveyor-belt principle. As soon as the first section had been assembled it was fitted with the appropriate machinery, electrical equipment, messing accommodation etc., the same operation on each section being performed by the same workmen for the sake of speed.

The delivery of the completed sections to the U-boat assembly yards at Bremen (Deschimag), Hamburg (Blohm & Voss) and Danzig (Schichau), and the process of final assembly and launching, all had to follow a strict time-table, and it is not surprising that difficulties arose in the early stages of the programme. The section-building yards were at first unable to keep to the schedule, partly owing to delayed delivery from subcontractors of certain important fittings and partly to the first part-sections having been badly rolled and exceeding the specified tolerances, which necessitated additional work. As a consequence, the supposedly complete sections for the first boats arrived at the assembly yards late and in an unfinished state, which in their turn meant additional work in the time allotted for U-boat assembly. The Central Shipbuilding Committee, however, would permit no postponement of U-boat completion dates and ruthlessly insisted on strict observance of the timetable. The first boats to be launched, therefore, had much work outstanding – and a lot that was, perforce, skimped – so that they had later to spend long periods in dockyard hands. Indeed, so many imperfections showed up in the first seven boats that they could be used only for training and experimental purposes.

All these difficulties, together with prevailing differences of opinion, caused tension and antagonism between the Central Shipbuilding Committee, the Naval Command and the dockyard authorities. This unfortunate atmosphere prevailed until the summer of 1944, when there was a noticeable improvement, due in part to the influence of the Shipbuilding Commission, which under Admiral Topp had been created at the beginning of that year, and which thereafter acted as mediator between the Naval Command and the Armaments Ministry on behalf of the Shipbuilding Committee.

The war ended before the Germans could deploy their own next wave of technology embodied by the Type XXI ”Electric” boat, with much larger battery capacity that gave it a fast underwater speed. Until late 1944 Allied bombing had a disruptive rather than disastrous impact on the Type XXI program. The situation changed radically in 1945 when massive raids resulted in the destruction not only of U-boats still on the ways but also of completed U-boats fitting out, or, in some cases, after commissioning and while undergoing training. Thus, quite apart from the damage to construction facilities, 17 completed Type XXIs were sunk in harbour between December 31, 1944 and May 8, 1945: Hamburg – seven; Kiel – six; and Bremen – four.

In essence the Type XXI simply introduced too much that was new simultaneously and demanded too much of those involved in the program. The reasons for this were diverse. In part it was due to the impending defeat on the high seas and the desire to do something – anything – to prevent it. There was also a fascination in Germany for anything that was new and militarily impressive. With hindsight, there also appears to have been an air of unreality about many activities and decisions, some of which may have been due to the pressure of work and others plain ‘woolly thinking’. Unfortunately for the Kriegsmarine, the outcome of all the pressure and cutting of corners was that the boats that were actually completed were constantly having to return to the yards for repair and modification, resulting in delays in attaining full-service stratus.

Delays in completion and training

Owing to the circumstances already mentioned, the whole U-boat building programme gradually dropped about five months behind schedule and, although the first Type XXI boat was launched as planned in April 1944, she was not commissioned until June. By the end of October, 32 Type XXI and 18 Type XXIII had been commissioned, while those under construction in the assembly yards were so far advanced that, even allowing for considerable destruction through bombing, a monthly delivery rate of 15 to 20 Type XXI and six to ten Type XXIII could be expected in the immediate future. German records do not show the exact number of new-type boats completed; but from the record of those commissioned, it can be seen that the expected rate was generally achieved.

As was mentioned, the unorthodox methods used in the construction of these boats was responsible for an inordinate number of defects in the first to commission, and frequent interruptions for repair and modification combined to lengthen the crew training period from the usual three months to nearly six. However, by dint of close co-operation between the Construction Office at Blankenburg, the U-boat Acceptance Staff and the Admiral in Charge of U-boat Training, the fundamental defects were eliminated within a few months and, from the autumn onwards, the necessary modifications were incorporated into all U-boats delivered from the builders.

A nucleus of experienced U-boat commanders and petty officers formed the backbone of the new crews, who buckled down to their training with great enthusiasm. Meanwhile, the U-boat Command, which had previously studied the question of tactical employment of the new-type boats, had passed on their findings to the training, experimental and trials staffs and to the U-boat commanders. It was thus possible to put the new theories quickly to the test and to incorporate suggested improvements, which thereby hastened the process of establishing a firm basis for both crew training and operational use of the boats. The final “Battle Instructions for Type XXI and XXIII U-boats” were compiled from the evaluation of extensive sea trials carried out in one boat of each type, commanded by two well-trained officers, Korvettenkapitän Topp and Kapitänleutnant Emmermann.

Outstanding fighting qualities of the new boats

During the first Type XXI trials run over the measured mile at Hela, it was at once evident that the designed submerged full speed of 18 knots for one hour 40 minutes would not be realised, the maximum submerged speed attained varying between 16 and \7\ knots for from 60 to 80 minutes. However, at medium speeds of from 8 to 14 knots the disparity between design and performance was not so great, and the cruising motors came up to expectations with a speed of 5 to 5.1 knots.

A boat proceeding on cruising motors had to schnorkel for three hours daily to keep her batteries fully charged, and at a submerged cruising speed of five knots she could thus traverse the danger area between the Norwegian coast and the south of Iceland in about five days, raising her schnorkel on only five occasions. The schnorkel head was fitted with a Tunis aerial and coated with sorbo rubber as a protection against radar, so the boats were less vulnerable to location and attack from the air than hitherto. Even if the schnorkel were to be located by radar – which by virtue of its absorbent coating was only possible at short range – a boat would be in no great danger, since a sharp alteration of course coupled with a large increase in speed would quickly take her clear of the area and out of range of the aircraft’s sonobuoys; she could then continue for as long as necessary at the silent running speed of five knots, at which it was possible to cover more than 300 miles, or at two to three knots, a speed which she could maintain for 80 to 100 hours without having to schnorkel. The new boats had, therefore, a much better chance than the old type of reaching the Atlantic unobserved.

The silent submerged cruising speed of 5 to 5.1 knots was also an excellent attack speed and, in the event that this proved too slow, a convoy attack could always be pressed home by using high speed. This capability and the newly introduced echo-ranging gear and plotting-table, specially designed for use in such attacks, gave the Type XXI a decisive advantage over the old schnorkel boats. Furthermore, the Torpedo Trials Staff had developed a special instrument for so-called “programmed firing” in convoy attacks: as soon as a U-boat had succeeded in getting beneath a convoy, data collected by echo-ranging was converted and automatically set on the Lut torpedoes, which were then fired in spreads of six, at five- and fifteen-second intervals. The torpedoes opened out fanwise until their spread covered the extent of the convoy, when they began running in loops across its mean course, making good a slightly greater or lower speed, and in so doing covered the whole convoy. In theory these torpedoes were certain of hitting every ship of from 60 to 100 metres in length; and the theoretical possibility of 95 to 99 per cent hits in an average convoy was, in fact, achieved on firing trails.

In addition to the Lut, an improved torpedo was now available which was capable of homing onto propeller noises and virtually immune to Foxer.

Even if she did not entirely fulfil our expectations, the Type XXI U-boat was an excellent weapon when assessed against the A/S capability prevailing in 1944. She had overcome her worst teething troubles; and it was our intention to use a few of these boats within the next four months to resume the battle both in the Atlantic and in remote areas, later disposing an increasing number to the west of the British Isles. By virtue of its great endurance, the Type XXI could reach any part of the Atlantic and remain there for three to six weeks; it could, in fact, have just made the passage to Cape Town and back without refuelling.

It was decided that any attempt at submerged pack tactics, with the support of air reconnaissance, should be delayed until sufficient boats became available; but communication requirements for cooperation between Type XXI U-boats and aircraft had been dealt with and the procedures exercised. For reconnaissance west of the British Isles, the Luftwaffe intended to provide Do 335 aircraft, which by reason of their high speed of 430 to 470 mph could fly direct across the United Kingdom at night. FO U-boats did not believe that sufficient aircraft would be made available for proper support in such operations, despite the Luftwaffe’s assurances; however, he was convinced that good results could be obtained without them, since the Type XXI required only one encounter with a convoy – particularly in a remote area – to fire all its torpedoes, with great prospects of attaining a number of hits.