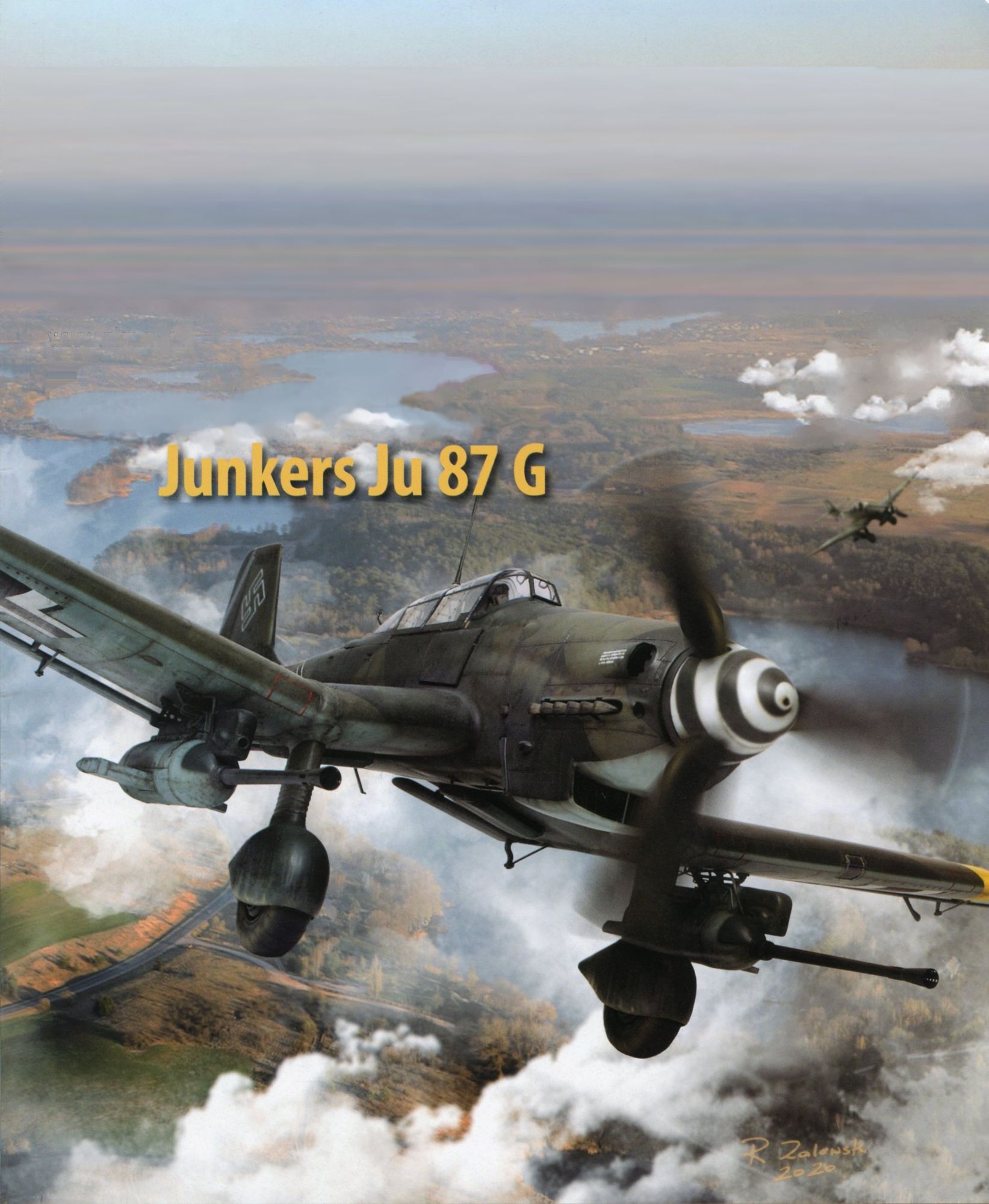

With the G variant, the aging airframe of the Ju 87 found new life as an anti-tank aircraft. This was the final operational version of the Stuka, and was deployed on the Eastern Front. The reverse in German military fortunes after 1943 and the appearance of huge numbers of well-armoured Soviet tanks caused Junkers to adapt the existing design to combat this new threat. The Hs 129B had proved a potent ground attack weapon, but its large fuel tanks made it vulnerable to enemy fire, prompting the RLM to say “that in the shortest possible time a replacement of the Hs 129 type must take place.” With Soviet tanks the priority targets, the development of a further variant as a successor to the Ju 87D began in November 1942. On 3 November, Erhard Milch raised the question of replacing the Ju 87, or redesigning it altogether. It was decided to keep the design as it was, but to upgrade the powerplant to a Jumo 211J, and add two 30 mm (1.18 in) cannon. The variant was also designed to carry a 1,000 kg (2,200 lb.) free-fall bomb load. Furthermore, the armoured protection of the Ilyushin Il-2 Sturmovik was copied, to protect the crew from ground fire now that the Ju 87 would be required to conduct low level attacks.

Hans-Ulrich Rudel, a Stuka ace, had suggested using two 37 mm (1.46 in) Flak 18 guns, each one in a self-contained under-wing gun pod, as the Bordkanone BK 3.7, after achieving success against Soviet tanks with the 20 mm MG 151/20 cannon. These gun pods were fitted to a Ju 87 D-1, W. Nr 2552 as “Gustav the tank killer”. The first flight of the machine took place on 31 January 1943, piloted by Hauptmann Hans-Karl Stepp. The continuing problems with about two dozens of the Ju 88P-1, and slow development of the Hs 129 B-3, each of them equipped with a large BK 7.5 cm (2.95 in) cannon in a conformal gun pod beneath the fuselage, meant the Ju 87G was put into production. In April 1943, the first production Ju 87 G-1s were delivered to front line units. The two 37 mm (1.46 in) cannons were mounted in under-wing gun pods, each loaded with a six round magazine of armour-piercing tungsten carbide ammunition. With these weapons, the Kanonenvogel (“cannon-bird”), as it was nicknamed, proved spectacularly successful in the hands of Stuka aces such as Rudel. The G-1 was converted from older D-series airframes, retaining the smaller wing, but without the dive brakes. The G-2 was similar to the G-1 except for use of the extended wing of the D-5. 208 G-2s were built and at least a further 22 more were converted from D-3 airframes.

Only a handful of production Gs were committed in the Battle of Kursk. On the opening day of the offensive, Hans-Ulrich Rudel flew the only “official” Ju 87 G, although a significant number of Ju 87D variants were fitted with the 37 mm (1.46 in) cannon, and operated as unofficial Ju 87 Gs before the battle. In June 1943, the RLM ordered 20 Ju 87Gs as production variants. The G-1 later influenced the design of the A-10 Thunderbolt II, with Hans Rudel’s book, Stuka Pilot being required reading for all members of the A-X project.

Hans-Ulrich Rudel in 1944.

Rudel on the Eastern Front

Rudel was determined to get into the action, and eventually a friend who commanded one of the wing’s squadrons relented, allowing him to fly as his wingman between his maintenance work on the flight line. He flew on the first day of the invasion of Russia and was in action on almost every day for the remainder of the war, except when he was in hospital or receiving medals from his Führer. The wing was in the thick of the action on the central sector of the Eastern Front, supporting panzer columns heading towards Smolensk and Moscow. Rudel became renowned for his determination to press home his dive-bombing runs, pulling up only at the very last minute to ensure his bombs landed on target

In August 1941, Rudel’s wing was transferred to the Leningrad Front where German troops were besieging the cradle of the Soviet revolution. With Germans on the outskirts of the city, several Soviet Navy ships trapped in the Gulf of Finland regularly turned their big guns on their enemies. The Immelmann wing was given the task of knocking out the warships. Its main target was the 26,416-tonne (26,000-ton) battleship Marat. The wing’s first attack on 21 September with 500kg (1100lb) bombs failed to penetrate the warship’s armour, in spite of Rudel putting a bomb square on target after flying through an anti-aircraft barrage thrown up by 1000 guns.

When 1000kg (2200lb) bombs arrived at the wing, Rudel led a new attack on the Marat. He pressed home the attack with his typical determination and only released his bomb 300m (980ft) above the target. Rudel’s bomb penetrated the warship’s magazine. As it exploded in a massive fireball, Rudel struggled to regain control of his aircraft after blacking out, and only managed to pull it up 4m (12ft) from the sea. If that was not enough of a problem, three Soviet fighters now jumped the Stukas. The attack won Rudel the Knight’s Cross.

The Soviet winter offensive of 1941–42 saw the Immelmann wing supporting hard-pressed German defences in central Russia. When a Soviet tank column broke through the front and threatened the wing’s airfield, Rudel led air strikes that drove them back. For three days, the Stukas kept the Soviets at bay until the Waffen-SS Das Reich Division arrived to relieve the situation. By now Rudel had notched up more than 500 missions and was posted home to train a new Stuka squadron. Not wanting to be out of the action, he soon managed to pull a few strings and got his squadron transferred to southern Russia, where the Germans were pushing south to seize Stalin’s Caucasus oil wells. In the middle of the battle for Stalingrad, Rudel was diagnosed with jaundice but after spending a few days in a field hospital, he absented himself, returned to the front and took command of a squadron of the Immelmann wing. These were desperate days for the Luftwaffe in southern Russia. As Soviet tanks moved to surround the German Sixth Army in Stalingrad, units such as Rudel’s Stukas were needed to hold back the Red Army. The Soviet advance was rolling up one German airfield after another, making it more difficult for the short-range Stukas to help the trapped German soldiers.

Cannon Birds

Erich Rudel was now recalled to Germany to form the first experimental anti-tank Stuka unit equipped with the 37mm cannon-armed Ju 87s, dubbed “Cannon Birds’’ by their crews. Rudel took the unit to the Crimea to help counter a Soviet amphibious landing on the Kuban peninsula. The Cannon Birds proved to be an outstanding success against Soviet landing craft bringing troops and supplies ashore, with Rudel alone claiming 70 destroyed. Personally awarded the Oak Leaves to his Knight’s Cross by a grateful Führer for his work in the Kuban, Rudel was now posted back to the Immelmann wing in charge of its Ju 87 G-1 anti-tank squadron, in time to lead it during the July 1943 Kursk Offensive.

As expected, his squadron was in the thick of the action supporting II Waffen-SS Panzer Corps as it attacked on the southern axis of Operation Citadel. His Cannon Birds ranged ahead of the panzers, intercepting and destroying Soviet reserve tank columns moving to the front. Scores of tanks were claimed destroyed by Rudel and his wingmen, with the squadron commander alone claiming to have destroyed 12 T-34s on a single day. Experience taught the Stuka pilots to aim for vulnerable parts of the Soviet tanks, such as engine bays and turret roofs. The exhaust smoke of the Soviet tanks proved a useful aiming point for the Stuka gunners, and a hit against the engine often resulted in a catastrophic explosion. The Soviet practice of loading extra fuel drums on the rear of their tanks made them very vulnerable to Stuka cannon fire. To get a good shot at the T-34s, Rudel recommended dropping down to 15m (50ft) to give the Stuka pilot a good look at the target. Here the slow speed of the Stuka came into its own, because it gave the pilot plenty of time to lay his guns on target.

These attacks proved devastating to the morale of Soviet tank columns and the infantry who rode into the battle on the rear decks of the T-34s. To counter the Stuka threat the Soviets started to move anti-aircraft guns close to their tank columns. In turn, Rudel began to have a pair of bomb- and machine-gun-armed Stukas circling overhead as his Cannon Birds lined up for their attacks. The supporting Stukas would strafe and bomb Soviet anti-aircraft batteries that attempted to open fire. They also provided early warning of the appearance of Soviet fighters that were starting to challenge German air superiority on the Eastern Front. In spite of this covering fire, Rudel’s aircraft routinely returned to base full of bullet holes.

After Hitler’s Kursk Offensive stalled, the Soviets immediately opened a huge offensive against the northern wing of the German forces around Orel, opening a huge breach in the front. Rudel’s tank-killing Stukas were rushed northwards to help stabilize the situation and give ground reinforcements time to mobilize. In the midst of this chaos, Rudel’s aircraft was badly shot up, but he managed to make a forced landing behind German lines and return to the fray. Soviet offensives continued to require the close attention of the Immelmann wing, and Rudel was appointed to command its 3rd Group after his predecessor was killed in action. He had now flown some 1500 sorties and personally destroyed 60 Soviet tanks, earning him the Oak Leaves and Swords to his Knight’s Cross.

Time after time, his Stukas saved the day during the Soviet winter offensive in the Ukraine, culminating in a decisive intervention during the Battle of Kirovograd in November 1943, when Rudel and his pilots blunted an attack by hundreds of T-34s. By now Rudel and his Stuka pilots had been turned into national heroes, featuring almost daily in Nazi propaganda broadcasts announcing more tank kills, desperate situations saved and medals won. To the ordinary German soldiers, Rudel’s tank-killing Stukas were known as the “front fire brigade” because they were always called on to dampen down the most combustible sections of the front. While other Stuka units had switched to flying the two-engine Henschel Hs 129 armed with a 75mm cannon, or ground-attack versions of the Focke-Wulf Fw 190, Rudel stuck with his trusty Ju 87. Rudel’s squadron operated from rudimentary forward air strips, and his leadership was instrumental in keeping his ground crews working in freezing weather to put damaged aircraft back in the air time and time again, with minimal spares, tools and facilities. Once in the air, Rudel’s pilots followed him into attack after attack. He appeared fearless. Even when shot down over enemy territory, he somehow managed to escape and return to the cockpit of a Stuka. This incident followed a successful attack to destroy a bridge over the River Dnieper in March 1944. Twenty Soviet fighters swooped on his squadron, forcing one of Rudel’s pilots to land in territory held by the Red Army. Rudel landed to try to pick up his man, only to have his aircraft get stuck in mud. Russian soldiers captured Rudel and his two comrades. He swam a river and walked 50km (31 miles) in an escape bid. Two days later, he reached German lines and was soon back in the air.

Tank killing with the G-1 model Stuka became a Rudel speciality, and by August 1944 he claimed his 320th tank kill. The collapse of the German Army Group Centre in July 1944 brought the Immelmann wing northwards to the Courland peninsula, where it was thrown into one desperate battle after another. In October Rudel was promoted lieutenant-colonel and given command of his beloved Immelmann wing. There was little time to bask in the glory, and he had to lead his fliers to Hungary to help Waffen-SS panzer divisions blast a corridor through to 100,000 German troops besieged in Budapest. Soviet fighters were now swarming over the Eastern Front, making it highly dangerous for the lumbering Cannon Birds to go into action. In the space of a few days Rudel was shot down twice, but returned to the cockpit of a Stuka with his leg in a plaster cast. With more than 2400 missions in his log book and 463 tank kills claimed, Hitler made him the only recipient of the Knight’s Cross with Golden Oak Leaves with Swords and Diamonds in January 1945. Hitler tried to ground Germany’s most highly decorated soldier, but Rudel insisted on returning to combat duty leading his wing.

Russian tanks were now advancing into Silesia, and Rudel’s wing was transferred to try to contain the situation. Flying from German soil, Rudel’s Stukas were able to rescue several German units cut off trying to retreat westwards to safety. When the Soviets pushed a bridgehead over the River Oder in February 1945, Rudel threw his Stukas into action. He alone destroyed four Soviet tanks, before having an aircraft shot out from under him. After struggling back to base, Rudel took off again to continue knocking out more than a dozen Josef Stalin tanks. In the midst of another attack run his aircraft was blown apart by Soviet flak. Rudel woke up in a field hospital to find out his left leg had been amputated. Despite being told his flying days were finished, Germany’s top Stuka pilot had other ideas. Only six weeks later he was back flying from bases in Czechoslovakia. When Germany surrendered in May, he led the remnants of his Immelmann wing on a last flight to American-controlled airfields in southern Germany.

Tank Killers

Rudel was instrumental in developing the tactics of using cannon-armed aircraft in the anti-tank role. The exploits of his Stukas during the Battle of Kursk was the inspiration used by the United States Air Force in designing the A-10 Warthog tank-busting aircraft at the height of the Cold War, when there was a requirement to counter massed divisions of Soviet tanks in central Europe. This aircraft was built around a multi-barrelled cannon specifically to counter enemy tanks.

As a leader of warriors, Rudel was unsurpassed. He led from the front and set a pace that few could equal. In the course of 2530 missions, Rudel personally destroyed 517 Soviet tanks – the equivalent of five Soviet tank brigades. This was on top of a battleship, cruiser, 70 landing craft, 800 trucks, 150 artillery pieces, as well as numerous bunkers, bridges and supply dumps. He also managed to achieve nine confirmed air-to-air kills. Perhaps more striking was the fact that Rudel was shot down 30 times by ground fire, and wounded five times. On top of this, he successfully rescued six of his pilots who had been shot down behind enemy lines. This was the mark of the man, who ranked leading his men into battle as the highest duty of any soldier.