The RAF, outnumbered four to one, proved itself plane for plane and man for man better than the Luftwaffe. The British, not the Germans, came out master of the skies above Britain. It was the skill and heroism of the RAF pilots-pilots recruited not only from Britain itself but from Canada, Ireland, and the United States-that won the Battle for Britain and thereby, perhaps, the war itself. No tribute was ever more deserved than that which Churchill paid to these intrepid men: “Never before in human history was so much owed by so many to so few.”

Accounts of individual feats of heroism by RAF pilots are numberless. Here is the story of twenty-one-year-old Pilot Officer John Maurice Bentley Beard, D. F. M., as he himself told it:

I was supposed to be away on a day’s leave but dropped back to the airdrome to see if there was a letter from my wife. When I found out that all the squadrons had gone off into action, I decided to stand by, because obviously something big was happening. While I was climbing into my flying kit, our Hurricanes came slipping back out of the sky to refuel, reload ammunition, and take off again. The returning pilots were full of talk about flocks of enemy bombers and fighters which were trying to break through along the Thames Estuary. You couldn’t miss hitting them, they said. Off to the east I could hear the steady roll of anti-aircraft fire. It was a brilliant afternoon with a flawless blue sky. I was crazy to be off.

An instant later an aircraftsman rushed up with orders for me to make up a flight with some of the machines then reloading. My own Hurricane was a nice old kite, though it had a habit of flying left wing low at the slightest provocation. But since it had already accounted for fourteen German aircraft before I inherited it, I thought it had some luck, and I was glad when I squeezed myself into the same old seat again and grabbed the “stick.”

We took off in two flights (six fighters), and as we started to gain height over the station we were told over the R. T. (radiotelephone) to keep circling for a while until we were made up to a stronger force. That didn’t take long, and soon there was a complete squadron including a couple of Spitfires which had wandered in from somewhere.

Then came the big thrilling moment: action orders. Distantly I heard the hum of the generator in my R. T. earphones and then the voice of the ground controller crackling through with the call signs. Then the order: “Fifty plus bombers, one hundred plus fighters over Canterbury at 15,000 heading northeast. Your vector (steering course to intercept) nine zero degrees. Over!”

We were flying in four V formations of three. I was flying No. 3 in Red flight, which was the squadron leader’s and thus the leading flight. On we went, wing tips to left and right slowly rising and falling, the roar of our twelve Merlins drowning all other sound. We crossed over London, which, at 20,000 feet, seemed just a haze of smoke from its countless chimneys, with nothing visible except the faint glint of the barrage balloons and the wriggly silver line of the Thames.

I had too much to do watching the instruments and keeping formation to do much thinking. But once I caught a reflected glimpse of myself in the windscreen-a goggled, bloated, fat thing with the tube of my oxygen supply protruding gruesomely sideways from the mask which hid my mouth. Suddenly I was back at school again, on a hot afternoon when the Headmaster was taking the Sixth and droning on and on about the later Roman Emperors. The boy on my right was showing me surreptitiously some illustrations which he had pinched out of his father’s medical books during the last holidays. I looked like one of those pictures.

It was an amazingly vivid memory, as if school was only yesterday. And half my mind was thinking what wouldn’t I then have given to be sitting in a Hurricane belting along at 350 miles an hour and out for a kill. Me defending London! I grinned at my old self at the thought.

Minutes went by. Green fields and roads were now beneath us. I scanned the sky and the horizon for the first glimpse of the Germans. A new vector came through on the R. T. And we swung round with the sun behind us. Swift on the heels of this I heard Yellow flight leader call through the earphones. I looked quickly toward Yellow’s position, and there they were!

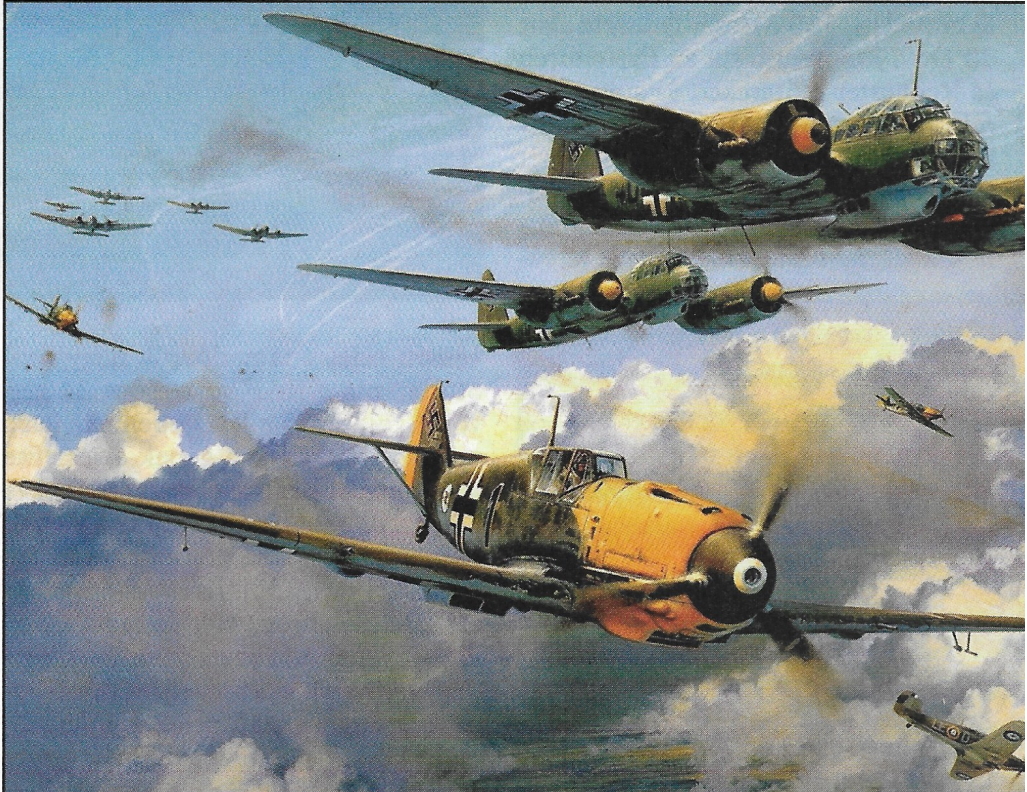

It was really a terrific sight and quite beautiful. First they seemed just a cloud of light as the sun caught the many glistening chromium parts of their engines, their windshields, and the spin of their airscrew discs. Then, as our squadron hurtled nearer, the details stood out. I could see the bright-yellow noses of Messerschmitt fighters sandwiching the bombers, and could even pick out some of the types. The sky seemed full of them, packed in layers thousands of feet deep. They came on steadily, wavering up and down along the horizon. “Oh, golly,” I thought, “golly, golly …”

And then any tension I had felt on the way suddenly left me. I was elated but very calm. I leaned over and switched on my reflector sight, flicked the catch on the gun button from “Safe” to “Fire,” and lowered my seat till the circle and dot on the reflector sight shone darkly red in front of my eyes.

The squadron leader’s voice came through the earphones, giving tactical orders. We swung round in a great circle to attack on their beam – into the thick of them. Then, on the order, down we went. I took my hand from the throttle lever so as to get both hands on the stick, and my thumb played neatly across the gun button. You have to steady a fighter just as you have to steady a rifle before you fire it.

My Merlin screamed as I went down in a steeply banked dive on to the tail of a forward line of Heinkels. I knew the air was full of aircraft flinging themselves about in all directions, but, hunched and snuggled down behind my sight, I was conscious only of the Heinkel I had picked out. As the angle of my dive increased, the enemy machine loomed larger in the sight field, heaved toward the red dot, and then he was there!

I had an instant’s flash of amazement at the Heinkel proceedingly so regularly on its way with a fighter on its tail. “Why doesn’t the fool move}” I thought, and actually caught myself flexing my muscles into the action / would have taken had I been he.

When he was square across the sight I pressed the button. There was a smooth trembling of my Hurricane as the eight-gun squirt shot out. I gave him a two-second burst and then another. Cordite fumes blew back into the cockpit, making an acrid mixture with the smell of hot oil and the air-compressors.

I saw my first burst go in and, just as I was on top of him and turning away, I noticed a red glow inside the bomber. I turned tightly into position again and now saw several short tongues of flame lick out along the fuselage. Then he went down in a spin, blanketed with smoke and with pieces flying off.

I left him plummeting down and, horsing back on my stick, climbed up again for more. The sky was clearing, but ahead toward London I saw a small, tight formation of bombers completely encircled by a ring of Messerschmitts. They were still heading north. As I raced forward, three flights of Spitfires came zooming up from beneath them in a sort of Princeof-Wales’s-feathers maneuver. They burst through upward and outward, their guns going all the time. They must have each got one, for an instant later I saw the most extraordinary sight of eight German bombers and fighters diving earthward together in flames.

I turned away again and streaked after some distant specks ahead. Diving down, I noticed that the running progress of the battle had brought me over London again. I could see the network of streets with the green space of Kensington Gardens, and I had an instant’s glimpse of the Round Pond, where I sailed boats when I was a child. In that moment, and as I was rapidly overhauling the Germans ahead, a Dornier 17 sped right across my line of flight, closely pursued by a Hurricane. And behind the Hurricane came two Messerschmitts. He was too intent to have seen them and they had not seen me! They were coming slightly toward me. It was perfect. A kick at the rudder and I swung in toward them, thumbed the gun button, and let them have it. The first burst was placed just the right distance ahead of the leading Messerschmitt. He ran slap into it and he simply came to pieces in the air. His companion, with one of the speediest and most brilliant “getouts” I have ever seen, went right away in a half Immelmann turn. I missed him completely. He must almost have been hit by the pieces of the leader but he got away. I hand it to him.

At that moment some instinct made me glance up at my rear-view mirror and spot two Messerschmitts closing in on my tail. Instantly I hauled back on the stick and streaked upward. And just in time. For as I flicked into the climb, I saw the tracer streaks pass beneath me. As I turned I had a quick look round the “office” (cockpit). My fuel reserve was running out and I had only about a second’s supply of ammunition left. I was certainly in no condition to take on two Messerschmitts. But they seemed no more eager than I was. Perhaps they were in the same position, for they turned away for home. I put my nose down and did likewise.

Only on the way back did I realize how hot I was. I had forgotten to adjust the ventilator apparatus in all the stress of the fighting, and hadn’t noticed the thermometer. With the sun on the windows all the time, the inside of the “office” was like an oven. Inside my flying suit I was in a bath of perspiration, and sweat was cascading down my face. I was dead tired and my neck ached from constantly turning my head on the lookout when going in and out of dog-fights. Over east the sky was flecked with A. A. Puffs, but I did not bother to investigate. Down I went, home.

At the station there was only time for a few minutes’ stretch, a hurried report to the Intelligence Officer, and a brief comparing of notes with the other pilots. So far my squadron seemed to be intact, in spite of a terrific two hours in which we had accounted for at least thirty enemy aircraft.

But there was more to come. It was now about 4 p. m., and I gulped down some tea while the ground crews checked my Hurricane. Then, with about three flights collected, we took off again. We seemed to be rather longer this time circling and gaining height above the station before the orders came through on the R. T. It was to patrol an area along the Thames Estuary at 20,000 feet. But we never got there.

We had no sooner got above the docks than we ran into the first lot of enemy bombers. They were coming up in line about 5,000 feet below us. The line stretched on and on across the horizon. Above, on our level, were assorted groups of enemy fighters. Some were already in action, with our fellows spinning and twirling among them. Again I got that tightening feeling at the throat, for it really was a sight to make you gasp.

But we all knew what to do. We went for the bombers. Kicking her over, I went down after the first of them, a Heinkel 111. He turned away as I approached, chiefly because some of our fellows had already broken into the line and had scattered it. Before I got up he had been joined by two more. They were forming a V and heading south across the river.

I went after them. Closing in on the tail of the left one, I ran into a stream of cross fire from all three. How it missed me I don’t know. For a second the whole air in front was thick with tracer trails. It seemed to be coming straight at me, only to curl away by the windows and go lazily past. I felt one slight bank, however, and glancing quickly, saw a small hole at the end of my starboard wing. Then, as the Heinkel drifted across my sights, I pressed the button-once-twice . . . Nothing happened.

I panicked for a moment till I looked down and saw that I had forgotten to turn the safety-catch knob to the “Fire” position. I flicked it over at once and in that instant saw that three bombers, to hasten their getaway, had jettisoned all their bombs. They seemed to peel off in a steady stream. We were over the southern outskirts of London now and I remember hoping that most of them would miss the little houses and plunge into fields.

But dropping the bombs did not help my Heinkel. I let him have a long burst at close range, which got him right in the “office.” I saw him turn slowly over and go down, and followed to give him another squirt. Just then there was a terrific crash in front of me. Something flew past my window, and the whole aircraft shook as the engine raced itself to pieces. I had been hit by A. A. fire aimed at the bombers, my airscrew had been blown off, and I was going down in a spin. The next few seconds were a bit wild and confused. I remember switching off and flinging back the sliding roof almost in one gesture. Then I tried to vault out through the roof. But I had forgotten to release my safety belt. As I fumbled at the pin the falling aircraft gave a twist which shot me through the open cover. Before I was free, the air stream hit me like a solid blow and knocked me sideways. I felt my arm hit something, and then I was falling over and over with fields and streets and sky gyrating madly past my eyes.

I grabbed at the rip cord on my chute. Missed it. Grabbed again. Missed it. That was no fun. Then I remember saying to myself, “This won’t do. Take it easy, take it slowly.” I tried again and found the rip cord grip and pulled. There was a terrific wrench at my thighs and then I was floating still and peacefully with my “brolly” canopy billowing above my head. The rest was lovely. I sat at my ease just floating gradually down, breathing deep, and looking around. I was drifting across London again at about 2,000 feet.

#

August saw large scale attacks on the ports-Portsmouth, Bournemouth, Dover-and on the southern airdromes, including Croydon. In the two great attacks of August 16 and 18 the Luftwaffe lost some 250 planes; in the fist ten days after they had launched their blitz they lost 697 planes to RAF losses of 153. Nor were the gains anywhere commensurate with these intolerable losses.

What did the enemy succeed in accomplishing in just under a month of heavy fighting during which he flung in squadron after squadron of the Luftwaffe without regard to the cost? His object, be it remembered, was to “ground” the fighters of the Royal Air Force and to destroy so large a number of pilots and aircraft as to put it, temporarily at least, out of action. . . . The Germans, after their opening heavy attacks on convoys and on Portsmouth and Portland, concentrated on fighter aerodromes, first on, or near the coast, and then on those farther inland. Though they had done damage to aerodromes both near the coast and inland and thus put the fighting efficiency of the Fighter Squadrons to considerable strain, they failed entirely to put them out of action. The staff and ground services worked day and night and the operations of our Fighting Squadrons were not in fact interrupted. By the 6th of September the Germans either believed that they had achieved success and that it only remained for them to bomb a defenceless London until it surrendered, or, following their prearranged plan, they automatically switched their attack against the capital because the moment had come to do so.

The first great blow came on September 7, when 375 bombers-a small number by 1945 standards but stupendous for that day-unloaded their bombs on the capital in full daylight. “This is the historic hour,” said Goering, “when our air force for the first time delivered its stroke right into the enemy’s heart.” Next day they were over London again, and the next, and the next, day after day, trying to knock out the world’s greatest city, break British morale, and bring Britain to her knees.

At first London was stunned-stunned but defiant. With astonishing rapidity and efficiency, the whole complex organization of anti-aircraft warfare and fire-fighting was brought into play. The RAF rose to challenge the invaders, and on one memorable day, September 15, shot down 185 Nazi aircraft. Fire-fighters worked day and night to cope with the flames which raged through the capital. Intrepid ambulance drivers – many of them mere girls-rescued the trapped and the wounded; wardens and other relief workers provided temporary food and shelter. And the anti-aircraft gunners threw a “roof over the city, forcing the enemy higher and higher into the skies.