Whilst the Americans headed to the south, British forces battled their way across northern Europe into Hamburg — Germany’s biggest port and its second city.

While the Allied armies in the south marched to the Alps. Montgomery’s 21 Army Group drove north and northeast. The British Second Army’s right wing reached the Elbe southeast of Hamburg on April 19, 1945. Its left fought for a week to capture Bremen, which fell on April 26. On April 29 the British made an assault crossing of the Elbe, supported on the following day by the recently reattached 18th Airborne Corps. Ahead lay the challenge of taking Germany’s biggest port and its second city – Hamburg.

On Montgomery’s left, meanwhile, one corps of the First Canadian Army reached the North Sea near the Dutch-German border on April 16, while another drove through the central Netherlands, trapping the German forces remaining in that country.

THE PUSH FOR HAMBURG

Squadron Leader Edgar Venning RAFVR, a Dental Officer with the Second Tactical Air Force, had maintained a diary since the day his Mobile Dental Surgery had gone ashore in Normandy after D-Day. The entries provide an intriguing record of his progress across northern Europe, an advance that was, at times, so rapid that Edgar noted “one can hardly keep pace with the events happening so fast all over Europe”. The date of this entry in his diary is May 3, 1945, the very day that both Littbeck and Hamburg were finally taken.

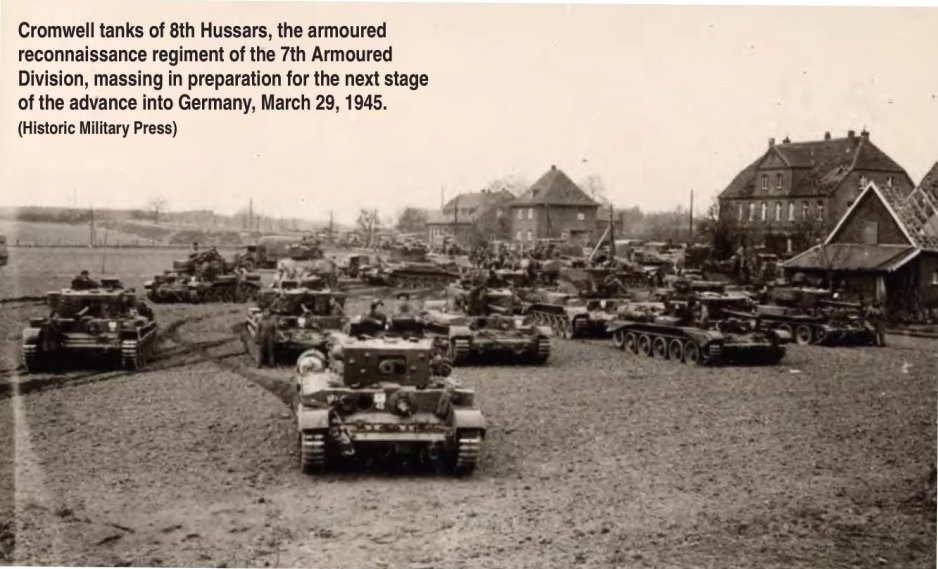

At times the drive on Hamburg had been fiercely contested by the Germans. On April 20, for example, the 8th Hussars and a company from the Rifle Brigade captured the town of Daerstorf, eight miles west of Harburg, but only after bitter house-to-house fighting and the deployment of Wasps, a version of the ubiquitous Universal Carrier fitted with a flamethrower, against enemy infantry and anti-tank gun positions.

The following day the Durham Light Infantry assaulted, and took, the village of Maschen, which lay 16 miles due south of Hamburg. In the surrounding woods were deployed a Hungarian SS unit, a German tank destroyer battalion and numerous Panzerfaust teams. It took the men of the 53rd Division, supported by the 1st Royal Tank Regiment, four days to dislodge them. Over 2,000 prisoners were taken in the process.

Then, under cover of darkness, at 02.30 hours on April 26, the Germans launched a counterattack near the village of Vahrendorf, some 14 miles south of Hamburg’s city centre. Symptomatic of the state of Hitler’s forces at this stage of the war, the attackers comprised a rag-tag assortment of members of the 12th SS Reinforcement Regiment, a smattering of ordinary soldiers, Hitler Jugend, impressed ships’ crews, stevedores, U-boat crewmen, Volkssturm and policemen and firemen from Hamburg. They were supported by a number of 88mm guns that were no longer deployed in the anti-aircraft role in the city.

The fighting in Vahrendorf raged throughout the day. At one point a pair of self-propelled 75mm guns worked their way into the village, seriously threatening the British line until a squadron of tanks arrived and resolved the situation. The enemy finally withdrew on April 27, leaving behind 60 dead and 70 prisoners.

SURRENDER

Bit by bit, though, the net continued to close around Hamburg. On April 28, British artillery shelled a number of targets in the city itself. The following day, on the instruction of the combat commander of Hamburg, Generalmajor Alwin Wolz, who had been appointed to the role on April 15, 1945, a deputation from the city was sent out to discuss surrender terms.

“The negotiations went on for some time,’ notes one account, “but on 1st May General Woltz’s [sic] staff car under a white flag approached the `D’ Company 9th DLI. Two staff officers were then taken to Battalion HQ. Admiral Doenitz had ordered General Keitel to order General Woltz to surrender the city of Hamburg to the Desert Rats… On 2nd May General Woltz arrived at Divisional HQ to discuss the arrangements for the surrender, which was [to be] taken by Brigadier Spurling on the afternoon of 3rd May 1945”!

As he later noted, Squadron Leader Venning suddenly found himself at the centre of events on May 3, experiencing the “excitement of being in one of the first few vehicles to enter”. The description of that final push into central Hamburg is best left to Edgar:

“The Doc. and I had no queue of patients, so we accepted the invitation of… the Official Observer RAE, attached to 83 Group, to accompany him by Jeep into Hamburg, which at noon that day was to be taken over… by our own Second Army.

“For an hour or so we sped along the bumpy cobbled roads on an army route to Winson [due south of Hamburg] and there turned onto the road to Hamburg.

Some way along the road we remarked that we were no longer on an army marked route and, moreover, there were no army vehicles or personnel to be seen. We were just wondering what were the chances of meeting a pocket of resistance, and whether we should turn back, when we encountered a little group of men trudging along – a dozen or so German soldiers carrying a white flag in front of them.

“We stopped – and they stopped. Most of them were very young and some looked only 16 or so. So, we told them to carry on marching, and pressed on towards Hamburg. But the bridge on the main Hamburg road had been blown up, so we had to go back and find a different route.

“Soon, to our relief, we came across a village where a lot of army vehicles were parked by the roadside. And here we learnt that there had been a hitch – the army had not yet gone in… long lines of tanks were waiting round the corner for the word `go.

“In our RAF Jeep, clearly marked `Official Observer, we cruised along past the long lines of tanks, Bren gun carriers and so on and, just as we reached the head of the column, they started to move off. We watched as these huge armoured vehicles went forward in battle array – a most impressive sight. They weren’t taking any chances – it was to be a military operation, not a triumphal parade.

“Our Official Observer wasn’t going to miss this, and much to amusement of the blokes in the tanks, drove on towards Hamburg. It was an amazing drive. There was, of course, no resistance at all. In fact, in the outskirts the Germans were lining the streets, wide-eyed with relief and undoubtedly pleased that for them it was all over. Many were waving, if a little self-consciously”

Some way along the road we remarked that we were no longer on an army marked route and, moreover, there were no army vehicles or personnel to be seen. We were just wondering what were the chances of meeting a pocket of resistance, and whether we should turn back, when we encountered a little group of men trudging along – a dozen or so German soldiers carrying a white flag in front of them.

“We stopped – and they stopped. Most of them were very young and some looked only 16 or so. So, we told them to carry on marching, and pressed on towards Hamburg. But the bridge on the main Hamburg road had been blown up, so we had to go back and find a different route. “Soon, to our relief, we came across a village where a lot of army vehicles were parked by the roadside. And here we learnt that there had been a hitch – the army had not yet gone in… long lines of tanks were waiting round the corner for the word `go.

“In our RAF Jeep, clearly marked `Official Observer, we cruised along past the long lines of tanks, Bren gun carriers and so on and, just as we reached the head of the column, they started to move off. We watched as these huge armoured vehicles went forward in battle array – a most impressive sight. They weren’t taking any chances – it was to be a military operation, not a triumphal parade.

“Our Official Observer wasn’t going to miss this, and much to amusement of the blokes in the tanks, drove on towards Hamburg. It was an amazing drive. There was, of course, no resistance at all. In fact, in the outskirts the Germans were lining the streets, wide-eyed with relief and undoubtedly pleased that for them it was all over. Many were waving, if a little self-consciously”

A DESOLATE, DEVASTATED AND DESERTED CITY

At this point, the convoy came to the bridges over the River Elbe, at which the tanks dispersed themselves at strategic points on either side of the road. As the crews awaited further instructions, the final advance on the city centre came to a temporary halt.

“We got into conversation with a Major of the Desert Rats [the 7th Armoured Division] whose Jeep was heading the convoy at the bridge,’ continued Venning. “He took a pretty good view of the job the RAF had done – and advised us to tag on behind him. Eventually the message came through to proceed, the battalion commander came up in his armoured car, and we all moved forward into the heart of the city.

“It was like a city of the dead. By a British order, a forty-eight-hour curfew kept everyone indoors and behind closed windows and shutters… We drove through a desolate, devastated and deserted city, with piles of rubble and twisted steel on either side of the road”

Large sections of the city had been devastated by Allied bombing, though around the central square and the Rathaus, or Town Hall, the damage was visibly less. For Edgar and his colleagues, the empty roads meant that they could sweep on towards the city centre. “Since leaving the bridge,’ he recalled, “the road had been lined on both sides by German military police, every 100 yards, in long green greatcoats and impressive helmets. Many saluted as the convoy went by – no Nazi Heil, but a deferential cap salute…

“We drove to the Town Hall square and there were a bunch of Nazi officials on the steps of the Rathaus awaiting the Brigadier. All the tanks and Jeeps and armour piled into this vast city square behind us, and soon the [German] officer with the white flag arrived, followed by the Brigadier. They entered the building amid much saluting and heel-clicking and photography.’

AN OPEN CITY

One reporter had managed to send through the following report that was published in an evening edition on May 3: “Hamburg, Germany’s greatest port and chief pocket of resistance along the North Sea coast, fell to the British today without a shot being fired. At nine o’clock this morning, a few hours after Gen. Dempsey’s columns completely isolated the garrison by their dash to the Baltic near Luebeck [sic], Hamburg Radio announced that the port had been declared an open city and that the British would begin its occupation at noon…

“Hamburg, second city of the pre-war Reich, contained 1,430,000 people and possessed 110 miles of docks and landing stages. Its capture is easily the biggest prize to fall to British troops since D-Day. Reuter’s radio station says it is evident that Hamburg radio station, formerly the Germans’ chief transmitter in the North, is now operating under Allied control.

“Hamburg’s fall, only one day after the capitulation in Italy… deprives the dying German Army of a northern stronghold and adds emphasis to the reports that the Germans in Denmark are ready to surrender. Hamburg is the first of German cities to be declared open and undefended, says A. P. [Associated Press]. The Secretary of State, Ahrendt, read the official announcement in a dull listless voice. At one point he choked, and remained silent for a few seconds. He spoke very slowly.

“In making the announcement, Hamburg Radio said: `All public traffic and vehicles must stop when occupation takes place at 12 noon. From 1pm there will be a curfew for the population, with the exception of the staffs of the electricity, gas and other works. The length of curfew will depend on the carrying out of all orders. The Hamburg police will be responsible for the enforcing of the curfew. In case of disobedience the occupation authorities will help in enforcing it?”

“TERRIBLE DESTRUCTION”

For Edgar, the next 24 hours were full of some of the most `extraordinary’ sights he would ever witness: “Hundreds of German soldiers drifting back, some walking, overburdened with kit, trudging wearily, some on bikes, many hundreds in long convoys of farm carts, some in vans and lorries of all kinds – all trekking back to find someone to give themselves up to. All looked weary, miserable, – and quite bedraggled, unshaven, and dirty quite often nonplussed”

One of the British soldiers present would later recall that he witnessed “terrible destruction in Hamburg. The roads were badly potholed, and piles of rubble on each side had been made into temporary homes. We were told the Germans dare not try to clear the debris because so many bodies were buried under it – they had no medical supplies to fight the epidemic which would follow”

One of the officers in the armoured column with Squadron Leader Venning, Lieutenant Brett-Smith, also kept a diary. In this he noted that “everything the RAF had claimed was true – Hamburg had ceased to exist… yet the streets were absolutely clear… no broken glass, nothing lying about in the streets… But at the same the damage was terrific – not single houses but whole streets were flat?

As the Gloucester Citizen newspaper account noted, Hamburg had indeed marked the last remaining defence for the Germans in the north of their country. After the British had captured the city, the surviving troops of the 1st Parachute Army along with the remains of Army Group Northwest retreated into the Jutland Peninsula. However, the battle that really signalled the end of the Reich had been taking place some 170 miles southeast in Berlin itself.