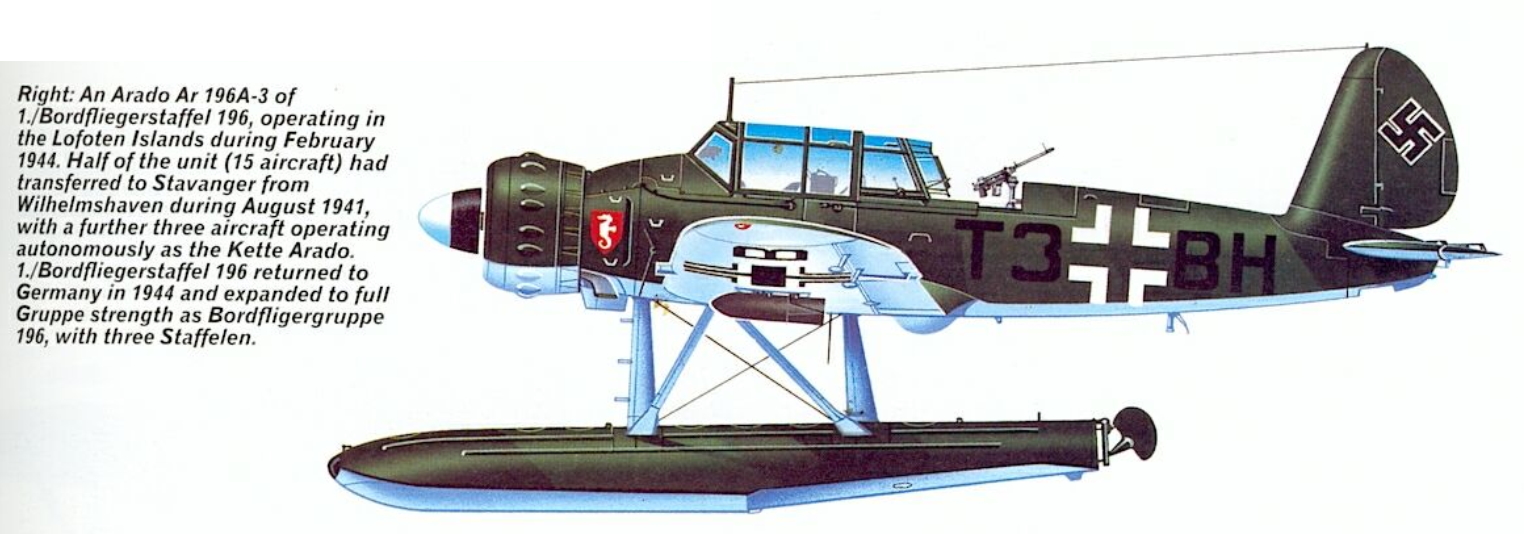

On the evening of 7 October the battleship Gneisenau and light cruiser Köln sailed from the Jade into the North Sea, accompanied by the destroyers Wilhelm Heidkamp, Friedrich Ihn, Diether von Roeder, Karl Galster, Theodor Riedel, Max Schulz, Bernd von Arnim and Friedrich Eckoldt. They were to bolster the war against merchant shipping while also attempting to lure British heavy surface forces from their bases into bomber range, in the mistaken belief that the major German units might be attempting to break into the Atlantic Ocean. After one day at sea, one of the ship’s two Arado Ar 196A-1s, T3+CH of 1./B.Fl.Gr. 196, was lightly damaged by its own catapult air pressure while being prepared for launch 30nm west of Utsire, after the ship was approached by a British reconnaissance aircraft.

While the Gneisenau group headed north, the Küstenflieger continued to traverse the North Sea, looking for the Home Fleet. HMS Selkirk and Niger were machine-gunned and attacked with bombs by Do 18s on 7 October while sweeping for mines off Swarte bank, 45 miles ENE of Cromer, though the strafing caused only light damage. The following day, Lt.z.S. Hans Wilhelm H. Hornkohl’s Do 18D3, M7+UK of 2./Kü.Fl. Gr. 506, was attacked by three Hudson Mk.Is of RAF Coastal Command 224 Sqn engaged on the delayed ‘special reconnaissance’ of the Skaggerak approaches and shot down 60 miles north-east of Aberdeen. The pilot, Fw. Willy Erich Nahs, managed to ditch the aircraft successfully, and after the circling Hudsons watched all four crew climb into their dinghy, they sank the aircraft with gunfire. The Danish freighter SS Teddy rescued the four Germans, who were landed in Sweden and interned after attempts by the destroyers HMS Jervis and Jupiter to intercept and take the German airmen prisoner failed. They were soon repatriated to Germany, arriving home on 25 October.

During the day following the loss of Hornkohl’s aircraft, B-Dienst established that heavy British forces had put out into the North Sea, detecting the 1st British Battleship Squadron, 2nd Cruiser Squadron and destroyers of the 6th and 7th Destroyer Flotillas. They had not, as yet, been found by aerial reconnaissance, and a greater-than-normal number of aircraft was despatched to the hunt, both Küstenflieger and aircraft of Geisler’s X.Fliegerkorps; the new nomenclature having been bestowed upon 10.Fliegerdivision on 2 October with a view to its imminent expansion. At 0800hrs the first of three sightings were reported by aircraft of 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 606, aircraft ‘J’ signalling the sighting of three enemy battleships and two destroyers in quadrant 4611, swiftly followed by aircraft ‘F’ reporting three cruisers and two destroyers in quadrant 3419, and aircraft ‘E’ three heavy cruisers and two destroyers in quadrant 3151, all located between the Shetland Islands and Norway. The latter two groups (designated ‘C’ and ‘B’ respectively and separated by 50nm), were listed as headed on a 90° course, while the direction of travel of the first reported group (designated ‘A’ and 80nm from ‘Group B’), was not included in the sighting report. Immediately, F.d.Luft designated the battleships of ‘Group A’ as the priority target.

At 0820hrs X.Fliegerkorps were informed by telephone of the three sighted enemy groups and, determined to demonstrate the capabilities of his forces, Geisler despatched a total of 127 He 111s and twenty-one Ju 88s of KG 26, KG 30 and LG 1 to intercept in staggered attacks throughout the course of the day. While KG 30 had previously been the sole operator of Ju 88s, Lehrgeschwader 1, which had been formed as a demonstration unit, and therefore had each Gruppen equipped with different aircraft types, had started to take on the Junkers fast bomber. Eventually, nearly all of LG 1 would be converted to the Ju 88, IV./LG 1 remaining the only Gruppe of the Geschwader to continue operating Ju 87s instead, and frequently served as part of the Luftwaffe’s maritime interdiction forces.

The staff of Küstenfliegergruppe 406 were ordered to co-ordinate an attack on ‘Group C’ by He 59s of 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 at 0840hrs, and within hours five torpedo-armed aircraft were airborne, accompanied by three others carrying smoke floats. However, the results obtained by this large aerial commitment were negligible. Weaknesses in nautical navigation among the conventional Luftwaffe crews had rendered sighting reports wildly inaccurate, the problem compounded by poor weather conditions which resulted in the previously smooth interplay of sighting, shadowing and attack, demonstrated previously against the Ark Royal, quickly becoming a shambles. The three separate groups later transpired to be just one that had been reported in various locations owing to imprecise navigation. The Royal Navy’s 2nd Cruiser Squadron, HMS Southampton, Glasgow and Edinburgh and five ‘J’-class destroyers, collectively known by the Admiralty as the ‘Humber Force’, had been sent to sweep northward off the Norwegian coast to prevent any planned German breakout of capital ships into the Atlantic indicated by Gneisenau’s sailing.

No concerted Luftwaffe attack was mounted, though small groups attempted to bomb sporadically, and erroneous reports of success were received by wireless in Germany. Of two 500kg bombs, 121 250kg and fifty-one 50kg bombs dropped during sixty-one separate attacks, seven hits were claimed; five 250kg bomb hits on cruisers, one amidships, causing flame and smoke and an explosion three minutes after impact, and two 50kg bomb hits despite heavy enemy flak. The Royal Navy recorded that HMS Jaguar, returning to Rosyth for fuel, had suffered an attack by two aircraft which had dropped six bombs, and an attempted dive-bombing attack by a Ju 88 which was deflected by anti-aircraft fire. The 2nd Cruiser Squadron came under attack at various intervals between 1120hrs and 1645hrs, though no ship was hit and only bomb splinters were found aboard HMS Southampton. At 1518hrs the two destroyers HMS Jervis and Jupiter were bombed by four aircraft which missed, but Jupiter’s engines broke down and forced Jervis to take her in tow for Scapa. In return, one Ju 88 was lost over the sea, though the crew were rescued, and three He 111s were lost, two crews being recovered.

On the part of the Küstenflieger, Hptm. Gerd Stein, Staffelkapitän of 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 706, recorded in his KTB at take-off:

I realise right now that if the enemy maintains his course, he will be out of my range. In the hope that the enemy will either be held up by the effect of the expected bombing raids made by the long-range division, or forced to alter course, I still head for the expected interception point.

Thus the Küstenflieger attempted its first torpedo operation of the war, sending out eight He 59s of 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 equipped with the lessthan-ideal F5. However, despite hours of searching they failed to contact the enemy, and lost He 59 8L+UL, which attempted an emergency alighting and crashed in heavy seas north-west of Sylt, the crew being drowned. A second He 59 was damaged by the same weather when, low on fuel, it was also forced to put down on the sea. The rest of the Staffel returned to their base after over eight hours in the air. Another aircraft, a Do 18 of 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 606, was also forced to make an emergency descent at sea near Lister, Norway, the crew and aircraft later being interned in Kristiansand until freed by the German invasion in April 1940.

In total, F.d.Luft later calculated that, at midday during the unfolding battle, twenty-three Do 18s were airborne in either picket lines or search patterns, plus the eight He 59s of 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 706, as well as 132 aircraft of X.Fliegerkorps. Nonetheless, despite the obvious failure in location and co-ordinated attack, the Kriegsmarine placed great store in the very fact that Luftwaffe aircraft were theoretically capable of dominating sea space far from German waters.

Apart from the immediate results of the bombing attacks, great strategic and operational importance is to be attached to the appearance of German operational air forces in the area of the northern part of the North Sea at such a long distance from their home bases. The fact that the enemy has become aware of the complete control of the entire North Sea area by the German Air Force will not be without a decisive effect on his considerations regarding operations in German coastal waters. In this way, he has been clearly shown for the first time the long range of German bomber forces and the danger to his bases and ports on the east and west coasts.

Eager for more tangible success, photographic-reconnaissance Heinkels of KG 26 detected a concentration of Royal Navy capital ships in the Firth of Forth on the morning of 16 October, and successfully evaded Spitfires attempting to intercept them. Their radioed reports of the sighting, including the belief that HMS Hood was within the estuary, brought twelve Junkers Ju 88A-1s of Hptm. Helmuth Pohle’s KG 30 to readiness on the island of Sylt. The Ju 88s departed in four separate waves of three aircraft each; Pohle leading the way, followed by the second group led by his executive officer, Oblt. Hans Siegmund Storp, a veteran of service in AS/88 during the Spanish Civil War and brother to Oblt. Walter Storp, former commander of the testing unit Erprobungsstaffel Ju 88 and now also in KG 30. They had been informed by Luftwaffe intelligence that there were no Spitfire squadrons based in Scotland, and were content to rely on their aircrafts’ speed to outrun any defences.

After making landfall as planned, the Ju 88s dive-bombed various capital ships within the estuary between 1434hrs and 1654hr. They had been ordered to sink the Hood but hamstrung by operational instructions that had been issued by Hitler, forbidding attacks on ships in dry dock, or on any land targets on Britain, to minimise the risk of civilian casualties. The ship believed to have been HMS Hood was in fact Repulse, which had clearly been placed into dry dock and was therefore off limits. There remained, however, several cruisers and the carrier HMS Furious as Pohle led the first attack against HMS Southampton. His steep 80-degree dive angle tore the canopy roof from his aircraft, taking with it the defensive rear machine gun, but he released bombs successfully at 550m and pulled out of the dive to the estuary’s north bank, where he planned to orbit and observe subsequent attacks. Storp’s second wave followed, his aircraft again targeting HMS Southampton. A single bomb hit the bow, slicing through three decks before bursting out of the hull above the waterline and exploding, blowing the admiral’s barge and a pinnace moored alongside into the air. The raid was observed by passengers on a train stopped at the southern arch of the Forth Bridge, at first believed to be the Germans’ target, as Storp’s and two other Ju 88s of his second wave flew parallel to observers on the bridge while coming out of their dives.

By this time, the unexpected arrival of Spitfires from Edinburgh’s 603 Sqn scattered the attacking bombers as they gave chase. Storp’s Junkers was hit by machine-gun fire, stopping his port engine and killing rear gunner Ogfr. Kramer. Further strikes disabled the elevators, after which the Junkers crashed into the sea near the coast at Port Seton; the first German aircraft brought down over Britain in the Second World War. Storp was thrown clear by the impact, and he and his two surviving crew, Fw. Hans Georg Heilscher and Hugo Rohnke, were picked up by the fishing boat Dayspring and taken ashore as prisoners. Storp gave the fishing boat’s captain, John Dickson Snr, his gold ring as a token of gratitude for their rescue. Glasgow’s 602 Sqn also arrived, ignoring an unidentified twin-engine aircraft sighted three miles from the scene of the action to intercept three distant aircraft, which turned out to be a trio of naval Skuas on a training flight from Donibristle. Retracing their path, they approached the previously unidentified aircraft, which was now identified as a Junkers. It was commanded by Pohl, who continued to circle while observing the attack. Bullets hit the port wing as Pohl hurriedly sought cloud cover but was outpaced by the pursuing Spitfires. As they attempted to climb away, the Ju 88’s cockpit was struck again by machine-gun fire, killing pilot Fw. Werner Weise and rear gunner seventeen-year-old Gefr. August Schleicher, and wounding the radio operator, nineteen-year-old Uffz. Kurt Seydel. Fuel tanks were soon ruptured and the starboard engine damaged, and Pohl was forced to ditch near a trawler that he fervently hoped would be the Luftwaffe Seenotdienst boat Fl.B213, based in Hörnum and positioned for the purpose of rescuing crews shot down during the raid. However, the trawler was British, and Pohl and his radio operator were pulled aboard, where the latter died of his wounds. Pohl had received wounds to his face and was later transferred to a military hospital in Edinburgh Castle before incarceration in Grizedale Hall. Although Weise’s body was never recovered, Schleicher’s was found, and both he and Seydel were later given military funerals as RAF pipers played Over the Sea to Skye as a lament. Nearly 10,000 people lined Edinburgh’s streets for the funeral procession of the two German airmen, 603 Sqn’s chaplain, the Reverend James Rossie Brown, delivering a moving eulogy and later personally writing to their families in Germany to assure them that their sons had been buried with full military honours. A pair of wreathes were placed on the airmen’s graves at Portobello Cemetery, reading: ‘To two brave airmen from the mother of an airman’, and ‘With the deep sympathy of Scottish mothers’. The dehumanising effect of war had not yet touched this part of Scotland.

As Pohle was being shot down, the fourth wave of Ju 88s attacked HMS Mohawk in an inbound Scandinavian convoy escort, bombs from Lt. Horst von Riesen’s Junkers bursting close alongside and sending lethal flying splinters scything through crewmen. Machine-gun fire from the bombers’ gunners added to the casualties, and the ship’s first lieutenant and thirteen men were killed. The captain, Cder Richard Frank Jolly, was mortally wounded in the stomach but stayed at his post until HMS Mohawk reached its berth in Rosyth, where he suddenly collapsed, dying five hours later.

In total, HMS Southampton, Edinburgh and Mohawk had all been damaged, and sixteen Royal Navy men were killed and forty-four injured for the loss of two Luftwaffe aircraft, albeit crewed by the Staffel’s senior officers. One of the Junkers of the third wave to attack was chased at low level over the centre of Edinburgh by Spitfires, but escaped, although stray bullets from the engagement hit a building under refurbishment and wounded a painter in the stomach.

The following day four KG 30 Ju 88s on an armed reconnaissance mission (German terminology for ‘shipping harassment’) over Scapa Flow, led by the newly promoted Gruppenkommandeur I./KG,30, Major Fritz Doench, attacked the unseaworthy and partly stripped obsolete battleship HMS Iron Duke, lying in the Flow as guardship only days after the sinking of HMS Royal Oak by Günther Prien’s U47. Two 500kg bombs hit the dilapidated ship, which was severely damaged and forced to beach in Ore Bay with a heavy list to port and one rating killed. A single Junkers piloted by Oblt. Walter Flaemig was brought down in flames by anti-aircraft fire from Rysa Little, crashing at the mouth of Pegal Burn on the Isle of Hoy. Only wireless operator Uffz. Fritz Ambrosius survived. He released the upper escape hatch and was dragged away by the slipstream, still clutching the release handle. Although he was able to open his parachute as the aircraft plunged to the rocks below, he sustained serious injuries because his parachute had caught fire and he landed heavily. He spent a month in hospital after his capture. A second wave of KG 26 Heinkels also attacked the beached ship as workmen of the salvage firm Metal Industries Ltd were engaged in pumping out the vessel and patching the hull, but the bomb run was inaccurate and they failed to hit anywhere near the target.

While the losses suffered by X.Fliegerkorps were considered relatively acceptable, there was growing Luftwaffe concern over the comparatively heavy casualty rate suffered by squadrons operating the Do 18, at that time the only available long-range reconnaissance aircraft. Ten had been lost since the beginning of the war, and construction of a more robust replacement aircraft was once again prioritised, the Dornier being considered extremely vulnerable to enemy air attack. To underline the point, on 17 October 8L+DK of 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 606 had been shot down by Gloster Gladiators of 607 Sqn. Tasked with shadowing enemy shipping following an early-morning search mission for a missing Ju 88 of I./KG 30, Oblt.z.S. Siegfried Saloga reported a ‘light cruiser’ some 125nm east of Sunderland, which they later misidentified as the Polish destroyer Grom, whereas it was actually HMS Juno. A second Dornier was ordered to join Saloga, and at 1240hrs three Gladiators of 607 Sqn were sent off from Acklington to see off both Do 18s. At approximately 1330hrs they engaged Saloga’s aircraft. The flying boat was damaged, and retired quickly towards the east, eventually having to ditch 35nm east of Berwick less than a quarter of an hour later, stalling as it flared for alighting and crashing into the sea. Flight mechanic Uffz. Kurt Seydel was killed, while Saloga, pilot Uffz. Paul Grabbert and radio operator Oberfunkmaat Hillmar Grimm abandoned the aircraft in their liferaft, which proved to have been pierced by gunfire. The swimming Germans were later pulled from the sea by the crew of HMS Juno.

In the meantime, Saloga’s earlier contact report triggered the despatch of six He 115s of 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406 from List at 0957hrs on an armed reconnaissance of the area Flamborough Head-Aberdeen, along with an additional three equipped with bombs. At 1020hrs they were followed by thirteen He 111s of KG 26, which took off from Westerland and headed for the area under the scrutiny of the He 115s. At 1507hrs two He 115s of the Bombenkette found and attacked HMS Juno six sea miles north of Berwick, dropping four SC250 bombs without result. The Heinkel floatplanes were later attacked by the Gladiators of 607 Sqn, but the combat was inconclusive. The KG 26 bombers failed to located Juno and returned to their airfield.

Increased numbers of He 115s were arriving at Küstenflieger squadrons, though they were still incapable of carrying torpedoes into action owing to the F5’s deficiencies. Furthermore, their potential vulnerability to determined enemy defence was soon made glaringly apparent during a badly fumbled operation mounted in co-operation with X.Fliegerkorps on 21 October. Convoy FN24 from Methil to Orfordness was reported steaming north of Flamborough Head, and MGK West requested and was immediately granted permission to co-ordinate an air attack. Ten He 115s of 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406 were armed with bombs and prepared for the raid, and the initial attack wave was increased to include three Ju 88s of 1./KG 30. As the two aircraft types had vastly different capabilities, takeoffs were staggered to allow the Heinkels to arrive on target first, followed shortly by the faster Junkers bombers. However, the plan misfired badly, as the Ju 88s outpaced the slower floatplanes and arrived well in advance, delivering their bombing attacks and retreating at equally high speed. By the time the Küstenflieger were within sight of the target, at 1545hrs, RAF Spitfires of 72 Sqn and eleven Hurricanes of 46 Sqn were on protective patrol, alerted by the previous attack.

The Heinkels flew into heavy defensive fire, and their loose formation was soon broken up by the British fighters, each of the floatplanes attempting emergency manoeuvres against the more agile fighters. Within minutes four had been shot down. Oberleutnant zur See Heinz Schlicht and his two crewmates, Lt. Fritz Meyer and Uffz. Bernhard Wessels, were brought down into the sea, their aircraft crashing five miles off Spurn Head, Yorkshire and killing all on board. The crew’s bodies were carried by the tide until they were washed ashore at Mundesley and Happisburgh, Norfolk, and they were buried on 2 November. A second Heinkel, commanded by Oblt.z.S. Albert Peinemann, crashed while attempting to ditch after being severely damaged by the attacking fighters. Pilot Uffz. Günther Pahnke and Peinemann were both slightly injured, but radio operator Uffz. Hermann Einhaus was unscathed, and all were rescued by a British merchant ship. The following day their abandoned Heinkel was examined by the crew of a Do 18, who landed alongside before sinking it with gunfire. A third crew, led by Oblt.z.S. Günther Reymann, was also taken prisoner after an emergency alighting by pilot Fw. Rolf Findeisen, who was badly injured and admitted to hospital after being put ashore on British soil.

The fourth Heinkel brought down was piloted by Uffz. Helmuth Becker, who was killed in combat with Spitfire K9959, piloted by Australian Flt Lit Desmond Sheen of 72 Sqn.

Just nineteen days after his 22nd birthday . . . Des later described that battle as ‘Really good fun; as exciting a five minutes as anything you could wish for’.

‘A’ Flight was scrambled at 2.15pm, and ‘B’ Flight’s Blue section was put on readiness. Green section, led by Des in Spitfire K9959, was scrambled at 2.30pm. He and Flying Officer Thomas ‘Jimmy’ Elsdon were ordered to proceed to Spurn Head, and soon sighted a loose formation of 12-14 aircraft, which they identified as Heinkel He 115 three-seater floatplanes.

Des and Elsdon intercepted the formation about 15 miles south-east of Spurn Head. As the Spitfires neared, the three enemy subsections ‘split up and employed individual evasive tactics of steep turns, diving, climbing and throttling back’.

Des ‘fired all I had at one of them’, attacking from ‘dead astern’, at about a hundred yards’ distance. Then: ‘as I closed on my He 115, its rear gunner attempted to put me off my aim by blazing away with his weapon, but I soon silenced him. The next burst may have killed the pilot, for the Heinkel started to fly very erratically, and with this I turned away to look for another target.’

The Heinkel broke away and later ditched near the Danish ship Dagmar Clausen, Oblt.z.S. Gottfried Lenz having been wounded by the Spitfire’s bullets, and Uffz. Peter Großgart was rescued by the neutral steamer and returned to Germany two days later.

The disaster of 21 October was referred to by Raeder in conference with Hitler two days later, as Raeder attempted once more to urge greater naval control of such aerial operations or, at the very least, enhanced cooperation between Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe forces.

The attack by He 115s in the coastal waters off southern England resulted in the loss of four aircraft; this area therefore appears unsuitable for attacks. The C-in-C Navy declares that conclusions have already been drawn from this experience, namely that the anti-aircraft defences are apparently very strong along the southern part of the coast of England. The C-in-C Navy asks that no measures be taken as rumoured — for instance, that combined operations over the sea are being considered — for it is absolutely necessary to train and operate naval aircraft in closest co-operation with naval forces. The Führer declares that there is no question of such measures.

However, the entire event played further into the hands of the Luftwaffe elements that wanted to wrest control of maritime operations from the Kriegsmarine. On 15 November Göring ordered the reduction of the Küstenflieger to just nine long-range reconnaissance and nine multipurpose Staffeln. He strongly requested that Raeder withhold the slow seaplanes from enemy coastal operations, noting that the Luftwaffe was supposed to be the authority of activity over open sea if no fleet operations were taking place.

The grievous losses did little for the moral of Küstenfliegergruppe 406, the Kommodore Obstlt. Karl Stockmann complaining bitterly about the effectiveness of his seaplanes and requesting, unsuccessfully, that at least one Staffel be converted to Fw 200 bombers. Instead, his staff unit was diverted to responsibility for the formation of a new long-distance reconnaissance unit, the Transozeanstaffel under the command of Major Friedrich von Buddenbrock, previously of the F.d.Luft Ost staff. During August 1939 Hermann Göring, as Minister for Air, had ordered that all Lufthansa seaplanes be placed at the disposal of Luftwaffe command. Although he recommended the continuation of transatlantic passenger flights until the eve of war, the few available transocean Lufthansa aircraft operating in conjunction with catapult ships in the Atlantic were ordered back to Germany via Spain shortly after hostilities began, the catapult ships being directed to dock in neutral Las Palmas. By 15 September 1939 the Luftwaffe had authorised the formation of the Transozeanstaffel, and the first pair of former Lufthansa Do 26 flying boats, Seeadler and Seefalke, alighted at Friedrichshafen for transfer onwards to Travemünde in September. Four other Do 26s either in trials or under construction were soon added to the specialised Staffel, which was completed by the addition of three large Lufthansa Blohm & Voss Ha 139 floatplanes named Nordneer, Nordwind and Nordstern, and two smaller Dornier Do 24s. The catapult ship Friesenland was used for the operation of the Ha 139s, docked in Travemünde and made ready for exercises in January 1940. While the Staffel was still in its gestation, its personnel were subject to posting to units already in combat, aircraft commander/observer Hptm. Rücker being ordered by F.d.Luft to transfer to KG 26 on 10 January, leaving only a single observer officer on strength until the arrival of Kriegsmarine Oblt.z.S. Heinz Witt, though Witt was qualified as an observer and not as an aircraft commander. Buddenbrock subsequently complained to Generalmajor Hans Ritter as Gen.d.Lw.Ob.d.M., asking how the Transozeanstaffel was to reach operational readiness with such a shortage of observer commanders.

In reality, none of the Transozeanstaffel aircraft would be combat ready for several months, as they were being adapted from civilian to military use with the assistance of engineers from Dornier and Blohm & Voss. This entailed the fitting of machine guns, bomb-carrying gear and accompanying ballast to the erstwhile civilian aircraft, which was not without its difficulties. Not until February 1940 did MGK West request their immediate despatch to the covert German naval base inside Soviet Russia, Basis Nord, for the purpose of North Atlantic reconnaissance. The small Kriegsmarine outpost had been established at the small fishing port of Zapadnaya Litza, 120km west of Murmansk in the Motovsky Gulf. However, the aircraft were deemed unready, as trials were ongoing to establish the operational radii available to the various aircraft using the less fuel-economical water take-offs necessitated by the rather primitive facilities at the Soviet port. The results were disappointing. Naval command estimated that the ‘range for Ha 139 aeroplanes is 2,500km, for Do 26 aeroplanes 3,000km, i.e. just barely enough for the flight from North Base to Germany’. The MGK request was subsequently refused, and Buddenbrock’s Staffel would not see action until April 1940, during the invasion of Norway.

Meanwhile, in October 1939, the dislocation of naval air units caused by transfer of individual Staffeln from east to west as Poland approached collapse prompted a wholesale reorganisation of the Küstenfliegergruppen, most individual Staffeln being renumbered while Küstenfliegergruppe 306 was disbanded and two entirely new Gruppen formed. While Küstenfliegergruppe 106 remained unchanged, the following exhaustive reorganisation took place:

Kü.Fl.Gr. 306 was disbanded.

Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr. 306 became Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr. 406;

1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 306 became 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 806;

2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 306 became the core of 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406, with some men and equipment distributed elsewhere as reinforcements.

Kü.Fl.Gr. 406 was reorganised:

Stab became Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr. 506, replaced by former Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr. 306;

1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406 became 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506, replaced by former 2./ Kü.Fl.Gr. 506;

3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406 became 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506, replaced by 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 306.

Kü.Fl.Gr. 506 was reorganised:

Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr. 506 became Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr. 806, replaced by former Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr. 406;

1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506 became 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 806, replaced by former 1./ Kü.Fl.Gr. 406;

2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506 became 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406, replaced by new Staffel, 2./ Kü.Fl.Gr. 506;

3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506 was disbanded, replaced by renumbered 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406.

Kü.Fl.Gr. 606, consisting solely of 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 606, was disbanded when 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 606 was redesignated 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906. However, the decision was taken on 1 November to re-form the Küstenfliegergruppe with three Staffeln raised from scratch: 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 606, 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 606 and 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 606, plus Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr. 606. However, although this unit was originally destined for purely maritime operations and equipped with seaplanes, a fresh caveat was placed upon Kü.Fl.Gr. 606, requiring that it be re-equipped with Dornier Do 17 bombers with land undercarriages. Under the command of Obstlt. Hermann Edert, the new squadrons would be considered a land-based Kampfgruppe; a standard bomber formation. A single bomber of 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 606, 7T+CH, was kept in readiness at all times for maritime operations, the remainder eventually alternating between land and sea missions, though the latter became less prevalent with each passing week once the Küstenfliegergruppe was operational.

Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 was disbanded:

Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 became Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr. 906;

1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 became 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906;

3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 became 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906. Not until 1 January 1940 did Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 begin to re-form, 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 being created in Kiel-Holtenau, equipped with He 59s rather than their previous He 60s. In July 1940 Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 was formed in occupied Stavanger, and 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 following three years later in Tromsø.

Kü.Fl.Gr. 806 was created in Dievenow:

Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr.806 from former Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr.506;

1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 806 from former 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 306;

2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 806 from former 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506;

3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 806 built from scratch.

Kü.Fl.Gr. 906 was created in Kamp:

Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr. 906 (in Kamp) from former Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 (He 60);

1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906 (in Nest) from former 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 (He 60/ He 114)

2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906 (in Pillau) from former 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 606 (Do 18); 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 906 (in Norderney) from former 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 (He 59).

There was no respite from operations while this organisational upheaval was taking place, and the aircraft continued to fly. On 22 October six German destroyers carried out a sortie against merchant shipping in the Skagerrak as part of a general Kriegsmarine initiative to consolidate control of the North Sea approaches to the Baltic. Multiple reconnaissance flights mounted by the naval air arm revealed numerous steam trawlers in the Dogger Bank and Hoofden areas, thought likely to be British or working in conjunction with Allied intelligence-gathering. Channel lights continued to burn brightly along the British coast, as they did in Dutch waters, in addition to the remains of one of the unfortunate He 115s shot down during the botched attack on Convoy FN24 and Seydel’s Do 18 drifting twenty miles east of Hartlepool. The destroyers seized two neutrals west of Lindesnes, one Swede and one Finn, carrying contraband to England, while fourteen other neutrals were stopped and released.