While the aircraft of Trägergruppe 186 were soon removed from F.d.Luft Ost, the remaining squadrons continued their activities over Poland and the Baltic Sea. On 16 September SKL suggested that boarding commandos be formed from personnel of both 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 306 and 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 706 to augment the naval forces already tasked with the interdiction of merchant ships carrying contraband to Great Britain. Each small commando unit would comprise a naval officer observer supported by a Luftwaffe radioman and one or two soldiers drawn from the ground staff. They were to be carried into action aboard an He 59, which was capacious enough to accommodate the extra men, two float-equipped Ju 52s able to carry larger parties of men if required also being added to the complement. The officers received basic training in the intricacies of Prize Law and were soon operational within the Baltic Sea. The interdiction missions were mounted by pairs of aircraft, one maintaining a protective circle above while the other landed near the target vessel, which had been requested to stop by gunfire, a thrown message from the Heinkel, or flashed Morse signals. Once alongside, the officer was able to inspect the ship’s manifest. Any vessel suspected of carrying contraband was directed to Swinemünde, where it would be more thoroughly inspected and possibly interned as a legitimate Prize of War. Following their brief training in the art of boarding merchant ships, on 24 September SKL recorded that: ‘Naval air forces are permitted to carry out war against merchant shipping in compliance with prize regulations’.

It was soon found that prevailing winds often prevented safe landings, and that the most effective method of inspection involved signalling the suspect vessel while remaining aloft, directing the ship toward a German port or one of the Vorpostenboote waiting in predetermined locations. Once again, Paul Just was at the forefront of this new Küstenflieger initiative, this time as observer and aircraft commander aboard a Kü.Fl. Gr. 306 Heinkel.

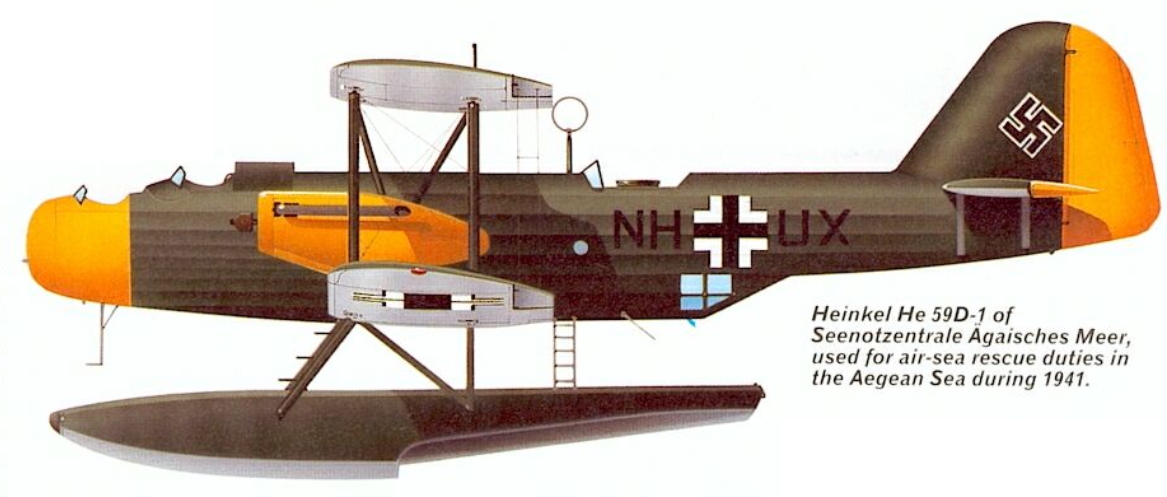

The He 59 is a good aircraft, but the two 600hp BMW engines can only give a maximum speed of 240km/h, the highest cruising speed only 205 km/h. The He 59 was intended for four men: Pilot and navigator up front, the radioman who doubled as an air gunner behind, and another gunner, the flight engineer, astern in the lower hull . . . Eight to ten aircraft are constantly on the move, and every day sixty to eighty merchant ships are inspected by the Vorpostenboote. It puts a great strain on the crews, with no possibility of collecting military glory . . .

My pilot, Bootsmann Brötsch, sits behind and above me. If I want to enter the control dome for a turn at the stick, I knock on his leg. He trims the machine, we understand each other with a look, and he drops out of his seat in the hull, I pull myself up. Of course, the change is prohibited, but the He 59 sails so well through the air, that probably nothing can happen; until the day it happens. When I’m up in the pilot’s seat, I unexpectedly see a crooked horizon. The machine is suddenly leaning almost 45 degrees to port. Brötsch is back in his seat in a flash. The machine straightens up, but the drone of the port motor is missing; the propeller has stopped. Theoretically, one engine should be sufficient to keep the He 59 airborne. Brötsch gives the starboard engine full power. The flight engineer, who also takes constant care of the aircraft when on the ground, feverishly searches for the cause of the failure. We can only hope that he is successful, because the aircraft has started to lose height.

Brötsch doesn’t need to say anything: we will be down soon. Worried, I look at the sea state, which is quiet, but with a few foam heads. Two steamers are all that are in sight, and as we go further down they disappear behind the horizon. We turn to face against the wind and wave direction. With the slow-running starboard engine we hold ourselves on course above the sea. But the He 59 lurches powerfully and it looks for a moment like the ends of the floats could hit the water and submerge. The fierce vibrations of the floating aircraft puts a great strain on us . . .

We radio a distress signal, because if the motor stops we will not be able to get it going again on our own. [The engineer shouts] ‘Everything is okay, I can’t find anything. Brötsch, give it another try!’ The starter makes the [port] engine pop and puff, the propeller turning in fits and starts before suddenly the engine runs again. We are amazed, and the pilot is happy.

In the west, co-operation between Admiral Alfred Saalwachter (MGK West) and both Joachim Coeler’s F.d.Luft West, Felmy’s Luftflotte 2 and Geisler’s 10.Fliegerdivision was initially very positive. Despite the fact that the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine had failed to co-ordinate the most basic tenets of cohesive maritime war (each used different map grids, there was no established mutual communications net, no common code or cypher system, and inadequate telecommunications between operational headquarters and command stations), an element of goodwill had been fostered, not least of all due to Coeler’s obvious enthusiasm for his aircraft to begin maritime operations. Overcoming the difficulties imposed by the joint control of naval air units, local organisational measures were taken between the various headquarters: Saalwachter based in Wilhelmshaven, Coeler in Jever thirteen miles to the west, Felmy in Brunswick, and Geisler’s office located in Hamburg, which boasted a highly developed signals net. The Luftwaffe and Naval offices immediately exchanged grid-square charts, enabling a composite overlay to be created to ease operational co-ordination. Communications systems were rapidly improved upon, and a Luftwaffe liaison officer was quickly assigned to Saalwachter’s staff. Felmy requested that a U-boat be assigned the task of sending direction-finder signals to aid aircraft navigation, but this was refused by B.d.U. on the grounds of meagre U-boat strength available for the war against British trade, a converted trawler Vorpostenboot being allocated instead for the same purpose.

Over the North Sea, aircraft controlled by F.d.Luft West mounted continuous reconnaissance missions to form a picture of shipping movements and the distribution of the Royal Navy’s Home Fleet. Aircraft also monitored the entrance to the Skagerrak for any indications of enemy minelaying, as well as any British naval forces despatched to reinforce Poland. First blood was drawn by one such reconnaissance flight within two days of the start of war with Great Britain. During the morning of 5 September eight He 115s of 1./ Ku.Fl.Gr. 106 took off from Norderney to fly their parallel search patterns. At approximately 0600hrs the crew of Lt.z.S. Bruno Bättger’s M2+FH sighted Avro Anson Mk.I K6183, VX-B, of 206 Sqn, RAF, south of the Dogger Bank, and attacked. The Anson was also engaged on maritime reconnaissance, as part of the new Coastal Command, having taken off from its home airfield at Bircham Newton to hunt for U-boats. Pilot Officer Laurence Hugh Edwards, a New Zealander who had trained with the RNZAF, engaged the He 115, and a fifteenminute battle followed. The Anson’s dorsal gunner, 22-year-old LAC John Quilter, was killed by gunfire. Edwards was unable to bring his forward machine gun to bear, and the Anson was soon on fire as it went down into the sea. Two other occupants, 23-year-old Sgt Alexander Oliver Heslop (of 9 Squadron, RAF) and 18-year-old AC1 Geoffrey Sheffield, were both killed, but Edwards manage to swim free of the wreckage despite suffering burns to his face and other minor wounds. The victorious He 115 alighted and rescued Edwards, who became the first RAF officer to be captured during the Second World War. Bättger’s triumph was to be short-lived, however, as his aircraft was shot down on 8 November by a 206 Sqn Anson. Bättger was posted as missing in action, but the bodies of pilot Uffz. Friedrich Grabbe and wireless operator Fkmt. Schettler were later recovered.

However, Coeler’s F.d.Luft West staff also suffered casualties during the first week of war. On 5 September a Junkers Ju 52 transport carrying six passengers was misidentified by flak gunners aboard the ‘pocket battleship’ Admiral Scheer and shot down. All aboard were killed, including Hptm. Günther Klünder, former commander of AS/88, who had been seconded to the staff of Führer der Seeluftstreitkräfte.

Only three He 60s were lost during the period between the opening of hostilities with Poland and the end of the year, all during September 1939. As well as the fatal crash in Pillau on 3 September, a second He 60 from 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506 crashed in the harbour on 11 September, shortly before alighting, after the pilot was momentarily blinded by sunlight. However, both he and the observer escaped unscathed. On 22 September an He 60 made an emergency landing off Kaaseberga near Kivik, Sweden, owing to engine problems during a reconnaissance sweep of the Bay of Danzig. Drifting toward Swedish territorial waters, the aircraft was subsequently taken in tow by the Swedish destroyer Vidar and landed at Ystad. Both the pilot, Oblt. Gerhard Grosse, and observer Lt.z.S. Helmut von Rabenau were initially interned but repatriated on 8 June 1940. The aircraft was not returned to Germany until 4 November of that year.

On 26 September the second He 59 destroyed during the month was lost when M2+SL of 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 106, one of nine patrolling the North Sea, was forced down by failure of the port engine. Observer Oblt.z.S. Deecke could see that the aircraft was steadily losing height and stood no chance of making landfall, and so ordered pilot Fw. Worms to put the Heinkel down, a strong breeze running the sea to a moderate and potentially dangerous swell. Unfortunately, as soon as the aircraft touched down, the starboard float struts broke on the choppy water and the wing cut under the sea surface. The aircraft was completely written off, its wreckage being recovered by the salvage ship Hans Rolshoven and the crew rescued and landed at Borkum.

Three of the few unsatisfactory He 114s in service were also lost during September. On 6 September T3+NH was destroyed while being lifted aboard the supply ship Westerwald, which was idling near Greenland in support of the ‘pocket battleship’ Deutschland. The aircraft smashed against the ship’s hull and was dropped back into the water, its engine later being salvaged. Five days later, observer Lt.z.S. Ralph Kapitzky and his pilot, Uffz. Nowack of 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506, were both slightly injured while alighting at their home base at Putzig following action against Polish troops at Grossendorf. During the attack on infantry positions, rifle and machine-gun fire had damaged the aircraft’s control system, causing Nowack to lose control during the landing run. Theirs was one of ten He 114s operated by the Staffel. A second was lost a week later when it crashed while alighting owing to an unexpectedly strong tailwind, though there were no casualties.

Six of the long-range reconnaissance Dornier Do 18s were also lost during September. Four days after the fatal crash of Do 18 M2+JK in Baltrum, an aircraft of 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 606 capsized during a night alighting at 2304hrs at Hörnum, after being diverted from Witternsee because of fog. Of its crew, observer Oblt.z.S. Helmut Rabach was posted as missing, his body never being recovered, flight engineer Uffz. Karl Evers was killed, pilot Uffz. Ernst Hinrichs was badly injured, and wireless operator Hptgfr. Herbert Rusch slightly injured. The aircraft, 8L+WK, was virtually destroyed and later written-off, and Hinrichs died of his injuries in hospital two days later. The Staffel 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 106 lost two aircraft within a day of each other, the first following an emergency alighting with engine trouble in the North Sea. Kapitänleutnent Karl Daublebsky von Eichhain rescued the crew, adrift in their lifeboat, with his coastal Type II U-boat U13. He also attempted to take the aircraft in tow, but repeated attempts failed in a worsening sea state. During the following morning the seaplane tender and Seenotdienst ship Günther Plüschow reached their position and also attempted to take the crippled Dornier in tow, but the waterlogged aircraft subsequently flooded and was finally sunk by gunfire at 1230hrs on 13 September.

That same day, near the sand dunes of Ameland, Do 18 M2+LK of the same Staffel washed ashore after being damaged by Dutch Fokker D.XXI fighters of 1st JaVA. Unlike the other Low Countries, The Netherlands actively defended their territorial air and sea space, and the Dutch fighters had been scrambled after a naval reconnaissance Fokker T.VIII-W floatplane was attacked six miles outside territorial waters off Schiermonnikoog Island by a German He 115 floatplane of Küstenfliegergruppe 406. The German crew had not recognised the approaching aircraft as Dutch, maintaining that, as it came out of the sun towards them, the national insignia of tricolour roundels looked either British or French. The Heinkel crew opened fire and brought the aircraft down, whereupon the T.VIII-W capsized. Recognising their error too late, the Heinkel crew descended alongside the upturned Fokker to assist the crew, some of whom were slightly injured. However, the He 115 was also slightly damaged by a short steep sea, and further assistance arrived in the form of the Do 18 flying boat commanded by Lt.z.S. Horst Rust. This too suffered minor damage upon alighting, but the Heinkel was eventually able to take off and transport the injured Dutch crew to hospital on Norderney. Meanwhile, alerted to the drama unfolding at sea by observers ashore, a patrol of three Fokker D.XXIs took off from Eelde, intending either to force the German aircraft to remain stationary and await naval interception, or attack should they attempt to flee. By the time they arrived at the scene the Heinkel had already left, but they sighted the stationary Dornier and fired initial warning shots ahead of the floatplane to prevent take-off. Pilot Fw. Otto Radons initially set course for the flying boat to head towards the Dutch coast, but then attempted to lift off and escape. A second strafing attack hit the Dornier, puncturing its hull, which began to leak in the heavy swell. Abandoned, the aircraft drifted ashore and was virtually destroyed by the surf, while Rust and his crew, who had taken to their lifeboat and paddled to the coastline, were captured and interned at Fort Spijkerboor, being taken to Great Britain as prisoners of war in May 1940.

Although the Luftwaffe immediately apologised for the incident, Dutch authorities also admitted some measure of culpability, and in an attempt to minimise such an event recurring, the Dutch Air Force substituted an orange triangle for their tricolour roundels, and their established red, white and blue rudder markings being changed for orange overall. This, however, did not prevent the misidentification of a Dutch DC-3 on 26 September, which was attacked by an He 115 of 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406, damaging the airliner and killing Swedish passenger Gustav Robert Lamm.

The forces available to F.d.Luft West were steadily increased as the war in Poland progressed in Germany’s favour. Gydnia fell on 14 September, Polish forces withdrawing to the Oksywie Heights, which in turn fell within five days. The Hela Peninsula was isolated and finally battered into submission by 2 October, and four days later the final Polish military units surrendered following the battle of Kock, marking the end of the German’s Polish campaign.

While ‘Fall Weiss’ neared completion in the east, the units of F.d.Luft West shared with Luftflotte 2 responsibility for the reporting of shipping movements and naval activity within the North Sea. The picture that was forming at MGK West instigated an intensification of operations against merchant shipping sailing in defiance of the declared blockade of Great Britain, in which both Kriegsmarine surface forces and naval aircraft could co-operate. The Luftwaffe crews of Luftflotte 2 still lacked the required naval training to guide German destroyers effectively towards suspicious merchant vessels, so the onus fell to F.d.Luft West, with its contingent of Kriegsmarine observers.

On 26 September 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 306, 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406 and 2./Kü.Fl. Gr. 506 were scheduled to mount eighteen separate reconnaissance flights over the North Sea in what had become a familiar routine. However, on this occasion they located strong elements of the Royal Navy Home Fleet that had thus far eluded them. Three main groups were reported and, to maintain contact, aircraft of 1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406 and 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 506 (transferred from the east and placed under the direction of Karl Stockmann’s Stab/Kü.Fl.Gr. 406) were also despatched to strengthen the reconnaissance sweep. The first group (Home Fleet) was observed heading east, and comprised two battleships, one aircraft carrier and four cruisers. The second (Humber Force), was sailing west, and consisted of two battlecruisers, (mistakenly) one aircraft carrier and five destroyers, and the final group, ‘heading for the west at high speed’, comprised two cruisers and six destroyers. Rather than spread the aircraft too thinly, contact was maintained on the two heavy groups only, and all W/T transmissions from the shadowing aircraft were immediately forwarded by F.d.Luft West to 10.Fliegerdivision so that they could prepare a bombing attack. Furthermore, Coeler ordered two multipurpose torpedo-carrying Staffeln to prepare an attack to follow-up the bombers, though the time taken to prepare the aircraft delayed take-off until 1330hrs.

At 0830 on 25 September the Home Fleet, comprising the battleships HMS Nelson and Rodney (of the 2nd Battle Squadron), the aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal (with the Blackburn Skuas of 800 Sqn, the Blackburn Skuas and Rocs of 803 Sqn, and the Fairey Swordfish of 810, 818, 820 and 821 Sqns embarked), and the destroyers HMS Bedouin, Punjabi, Tartar and Fury, had sailed from Scapa Flow, steering a westerly course to provide cover for the cruisers and destroyers of the Humber Force returning to British waters, escorting the submarine HMS Spearfish which had been damaged by German depth charges. The destroyers HMS Fame and Foresight were already at sea, and soon joined the main force, followed later by the destroyers HMS Somali, Eskimo, Mashona and Matabele.

At 1100hrs GMT three of the distant shadowing Dornier flying boats were sighted by Swordfish reconnaissance aircraft from Ark Royal, and nine Skuas were flown off in groups of three at hourly intervals to intercept. The first flight had trouble locating the shadowing aircraft, finally sighting 2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 306 Do 18 K6+XK and engaging in a protracted air combat, hitting the Dornier thirty-six times before it escaped using its superior speed. A second Do 18 of the same Staffel survived forty minutes in combat against Skuas of 803 Sqn, suffering fifty-five hits before managing to escape and later making an emergency landing. It was later recovered successfully. However, Leutnant zur See Wilhelm Frhr. von Reitzenstein’s Dornier Do 18, M7+YK of 2./ Kü.Fl.Gr. 506, was attacked by a flight from 803 Sqn at approximately 1203hrs GMT. Reitzenstein was sighted flying close to the surface of the water, and Lt B.S. McEwan RN and his air gunner, Acting Petty Officer Airman B.M. Seymour, disabled the Dornier’s engine, forcing it to make an emergency descent. All four crewmen took to their liferaft and were captured by HMS Somali, their crippled aircraft being sunk with gunfire. The shooting-down of Reitzenstein’s Dornier was the first confirmed German aircraft lost in aerial combat. A second Do 18 of 3./Kü.Fl.Gr. 106 was also lost, but to engine malfunction rather than enemy action. It made an emergency descent near Juist, whereupon the starboard float struts broke apart and the wings hit the water. Although it was later recovered by the Seenotdienst ship Hans Rolshoven, the Dornier was written-off. Nonetheless, the Küstenflieger aircrafts’ dogged perseverance in maintaining contact allowed a co-ordinated bombing attack to be made on the Home Fleet.

In the morning our air reconnaissance contacted heavy enemy forces north and west of the Great Fisher Bank. Despite strong enemy fighter defence and anti-aircraft gunfire, the shadowing aeroplanes succeeded in guiding four dive-bombing Ju 88s and one squadron of He 111s of 10 Fliegerdivision to the attack by sending out direction-finder signals.

The ships’ positions had been successfully reported and at 1345hrs, when the British Home Fleet was approximately 120nm west of Stavanger, HMS Rodney’s Type 79Y radar reported aircraft approaching. Nine He 111H bombers of the only operational ‘Löwen Geschwader’ Staffel, 4./ KG 26, from their forward airfield at Westerland, and four Ju 88A-1 bombers of 1./KG 30 from Jever airfield, were closing on their target at an altitude of 2,000m, attacking in the face of heavy anti-aircraft fire of all calibres but no fighter cover. All of the defending British aircraft had landed and been struck down to defuel, as dictated by Royal Navy policy at the time, which relied on anti-aircraft fire for fleet protection. Despite the strong defensive fire, no attacking bombers were hit, although it at least prevented German success.

All four Ju 88s targeted the Ark Royal, that flown by Uffz. Carl Francke, a former aeronautical engineer, being one of the last to make his dive-bombing attack with Ark Royal manoeuvring below him. A single SC 500 bomb exploded off the port bow, sending a huge column of water higher than the flight deck and causing the ship to whip and list alarmingly. Aboard the Ju 88 the water column was sighted along with a visible flash, though none of the crew could confirm whether it was an actual hit or simply the flash of gunfire obscured by smoke and water. One of the two bombs dropped was an established miss, but the second Francke reported as a ‘possible hit on bows; effect not observed’. Overoptimistically, MGK West counted the hit as definite, and by the time Francke had landed the wish had solidified into fact.

Result: One 500kg bomb hit by a Ju 88 on an aircraft carrier; two 250kg bomb hits by He 111 on one battleship. One miss by a Ju 88 on a cruiser. Results of hits by a Ju 88 on another battleship and a second aircraft carrier(?) were not observed owing to interception of the aeroplane. The fate of the hit aircraft carrier, which was not sighted again by further air reconnaissance, is unknown. If not sunk, at least heavy damage is presumed by the effect of the 500kg bomb. Own losses: Attacking formation; none. Reconnaissance formation; two Do 18s.

No British ships had actually been damaged, though HMS Hood had suffered a glancing blow from a bomb dropped by Lt. Walter Storp’s Ju 88 that bounced off the armoured hull plating, a large patch of grey paint being removed to show the red primer beneath. A second wave of bombers from KG 26 and KG 30 was cancelled, as arming the aircraft had taken too long, while F.d.Luft West was soon informed that his own He 59 torpedo bombers, which were almost ready to take off, would be unable to operate against the enemy owing to the extreme range. Nonetheless, the Germans believed that they had been triumphant. Further reconnaissance missions located heavy ships but failed to find any trace of HMS Ark Royal, though she docked in Scapa Flow two days later. In fact, the Kriegsmarine were not inclined to believe that the carrier had been sunk. They instead correctly reasoned that, as a result of incorrect location fixing, the aircraft had in fact sighted the Humber Force, which they no longer believed included an aircraft carrier. Nonetheless, the co-operation of the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine in this operation had proceeded smoothly and without significant issues. SKL recorded their summary of the event:

The success of the aerial attack by the operational Luftwaffe without any losses, entailing a distance of over 300 miles, is most satisfactory. It must be rated all the higher since it was the first operation of the war by the British Fleet in the North Sea, which has shown it in a very impressive manner the dangers of an approach to the German coast and, beyond that, the striking power of the Luftwaffe which threatens it. Any attempt by surface forces to penetrate into the Heligoland Bight or through the Kattegat and Baltic Sea entrances into the Baltic Sea must appear completely hopeless to the British Fleet after today’s experience – if it should be included at all in its operational plans.

The disposition of the bomber formations of the operational Air Force – providing for only four dive-bombing Ju 88 aeroplanes on Westerland at present, out of the small number so far available – rendered a more extensive use of the particularly suitable dive-bomber formations impossible. This must be regretted all the more as, after today’s experience, the British are not likely to repeat the operation, and the use of stronger Stuka formations would probably have had an annihilating effect. The co-operation of the reconnaissance formations of the Naval Air Force with the attacking formation of the operational Air Force, which is still rather inexperienced in flying over the sea, is particularly satisfactory: they stubbornly maintained contact with the enemy with remarkable persistence and despite the strongest fighter defence. Our Radio Monitoring Service worked well. In addition to the observation of heavy enemy forces in the North Sea yesterday, it was possible to gain important information as to course and speed of certain enemy groups by the decoding of enemy radiograms to enemy aeroplanes. The enemy anti-aircraft defence was of medium strength. The enemy fighters proved inadequate as to speed and daring.

German propaganda seized on the thin evidence of success and triumphantly reported the sinking of the Ark Royal, the Völkischer Beobachter and the Luftwaffe magazine Der Adler both publishing graphic artists’ impressions of the carrier wreathed in smoke and flames. Francke received a telegram of congratulations from Göring, and was promoted and awarded the Iron Cross First and Second Class, though at no point did he claim to have actually sunk the ship.

However, while the Kriegsmarine appeared content with the result of the combined operation, the resulting analysis by Luftwaffe staff had far-reaching consequences, as it contributed to an overinflated view of the effectiveness of Luftwaffe forces acting in isolation in action against enemy naval units. A report forwarded to Göring on 30 September by his Operations Staff Officer summarised that:

a. It can be assumed according to available data that the aircraft carrier was probably sunk. (The aircraft carrier not visible on the second comprehensive reconnaissance.)

b. According to the observations of the Ju 88 which attacked the carrier, it seemed that the strongly-cased 500kg SD delayed-action bomb caused an explosion inside the carrier among the oil reserves. (Apparent fires, smoke clouds.)

c. Even small Luftwaffe forces (thirteen aircraft) are in a position to inflict considerable damage on heavy naval forces.

d. In the rough sea (state four to five) the ships’ anti-aircraft guns were unable to break up the attack.19

Göring published an order on 29 September that all long-range reconnaissance over the North Sea was henceforth to be handled by Luftflotte 2, and frequent mistakes in Luftwaffe navigation resulted in an increased number of erroneous sighting reports which, though generally considered unreliable by MGK West, still required investigation by naval air units. The resultant waste of resources in duplicated and fruitless missions served to upset the uneasy calm that had been reached over operational jurisdiction between Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine tactical control.

On 3 October SKL enquired to Luftwaffe General Staff, Operations Division, about the possibility of the operational Luftwaffe conducting war against merchant shipping in accordance with prize regulations, and any plans for the conduct of war against merchant shipping during the ‘siege of Britain’. The answer, noted in the SKL War Diary, was both disappointing and predictable:

1. War against merchant shipping in accordance with prize regulations cannot be carried out by the units of the Luftwaffe.

2. Luftwaffe General Staff regards the main objective of the fight against Great Britain up to about spring 1940 to be against British Air Force armament factories. Suitable aircraft in sufficient numbers for effective participation in the blockade of Britain by sea west of Ireland will not be available until the end of 1940 or the beginning of 1941. Up to that time the blockade in the North Sea area by the Luftwaffe remains a task of secondary importance. It is planned effectively to support the blockade by combined attacks on the main enemy ports of entry and naval bases.

Meanwhile, elements of the Küstenflieger were also engaged in support of German destroyers attempting to intercept contraband merchant shipping in the Kattegat and Skagerrak bound for Great Britain, though this resulted in few seizures of cargo ships. In the Baltic the Naval Air Units continued to maintain their own blockade by stopping and searching steamers. Thirty-one had been intercepted by 9 October, and six taken as prizes to Swinemünde. Beginning on the evening of 27 September, aerial reconnaissance reported many ships hugging the coasts of Sweden, Denmark and Norway, sheltered by those nations’ neutrality. Only four steamers were successfully seized as prizes out of a total of forty-four stopped and searched, the majority travelling in ballast. However, the German concentration of aircraft, U-boats, S-boats and armed trawlers in the Skaggerak approaches had all but paralysed Danish export trade to Great Britain, and gave rise to Royal Navy Admiralty orders for a special reconnaissance patrol of Lockheed Hudsons to search the entrance to the Skagerrak to confirm reports of continuous German aerial patrolling, and ‘attack if circumstances prove favourable’. However, bad weather intervened during the following day, and most of the planned missions were cancelled. Grimsby fishing trawlers reported frequently sighted German flying boats; never more than two flying together, flying very low over the fishing fleet at between 200 to 500ft, though thus far no trawlers had been attacked.