The old post of Commander-in-Chief (the titular head of the British Army at Horse Guards that the Duke of York had held during his army reforms of the 1790s) had been scrapped in 1904. It had been replaced by a new office, Chief of the General Staff, but this was not vacant. Military plans to send a British Expeditionary Force (BEF) of six divisions to the Continent were being set in motion, but, once again, Kitchener was not the designated commander.

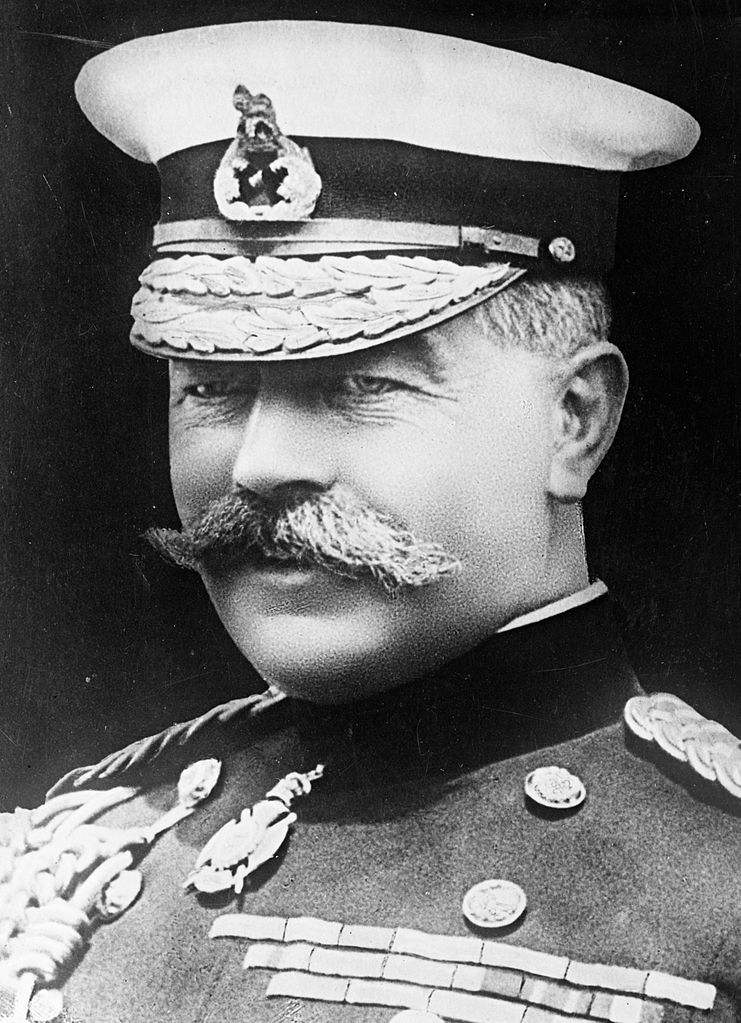

For several days prior to their meeting, the newspapers had been suggesting that Asquith might employ Kitchener as Secretary of War. Not everyone in Whitehall liked this idea, for it had been another aim of the 1904 reforms to conclude thirty-five years of military changes with civilian political control firmly and finally established over the War Office. What, then, would be the point of handing the top job to a soldier? Looking back at this situation, we might concede that late nineteenth-century reforms designed to make the army more efficient and check its Imperialist firebrands had gone a little too far, and that taking a soldier into the War Cabinet was quite justified in a time of total war.

As for Kitchener himself, he held the army’s central bureaucracy in complete contempt and was in the habit of denouncing it as hopelessly inefficient. His fear was that Asquith would ask him to be somebody’s deputy or invent some figurehead non-job. But the field marshal could read the papers like anyone else and knew that there was also a possibility of a cabinet post. At their meeting on the evening of 4 August, therefore, Kitchener asked the Prime Minister not to send him to the War Office unless it was with full powers as the Secretary of State for War. Asquith did not offer him the job, but decided to ponder it overnight.

There was palpable nervousness on the streets. Crowds gathered outside Buckingham Palace to cheer the King. Late editions of the papers were snapped up and scanned rapidly in case they carried news of a German climb-down. While many expected the war to be brief and heroic, there was a general understanding that the nation was facing an ordeal more testing than anything it had confronted since the time of Napoleon. Industrialisation and nationalism were about to produce a cataclysm of unrivalled ferocity. German unification had created a superpower in Central Europe and it was on a collision course with France. Allies stood ready on each side. The dread was summed up by a remark of Sir Edward Grey, the Foreign Secretary: ‘The lamps are going out all over Europe; we shall not see them lit again in our lifetime.’

On 5 August, Britain was at war. Ignoring Asquith’s ultimatum, the Germans were ploughing on relentlessly towards France, and under the terms of the Entente Cordiale, the alliance between London and Paris, the BEF was about to be committed to combat. Asquith therefore wasted no time in offering to make the field marshal Secretary of War. Kitchener was not in any sense a party animal so he made it clear to the Prime Minister that he would take the job only for the duration of the war and could not be expected to operate as a politician, publicly defending the government. ‘May God preserve me from the politicians!’ he remarked to a friend.

Asquith regarded the appointment of such an ingenue in the black arts of Whitehall as a risk. He was heartened, however, by the positive reaction of press and public. There was simply nobody else trusted to the same degree to face the looming darkness — a general European war — with the same nerve and toughness as Kitchener. Fifteen years earlier, people had said that K had absorbed the ‘Oriental’ qualities needed to prevail in the Middle East. In August 1914 his legend was reworked by those who felt his machine-like efficiency and toughness in South Africa meant he had the right stuff to beat ‘the Hun’ at his own game. One wag, observing the indomitable figure of the field marshal at a ball, supposed that he had ‘kinship to that old race of gigantic German Generals, spawned by Wotan in the Prussian plains, and born with spiked helmets ready on their heads’.

During the afternoon of the 5th, Asquith hosted a council of war at Downing Street. The Foreign Secretary was there, as was Winston Churchill, who had graduated from the cavalry subaltern Kitchener had met at Omdurman sixteen years earlier to running the Admiralty, and a couple of other senior military officers. During this meeting, Kitchener managed to upset the apple-cart of government strategic thinking completely.

The following morning, as he awaited the summons to Buckingham Palace to receive the seals of his office, Kitchener went to the War Office. Anxious to crack on with the job, he asked for the department’s senior officials to be presented. As they crowded into his room, pince-nez specs and winged collars aplenty, they were astounded by almost the first thing he said: ‘There is no army!’

At the first few meetings of the cabinet, Kitchener continued to surprise everybody. Unfortunately, cabinet minutes were not formally taken before December 1916, so there is no precise record of what he told them. The following account by Churchill, present at all the key meetings, gives the best sense of how Kitchener deployed his arguments:

Lord Kitchener now came forward to the Cabinet, on almost the first occasion after he joined us, and in soldierly sentences proclaimed a series of inspiring and prophetic truths. Every one expected the war would be short; but wars took unexpected courses and we must now prepare for a long struggle. Such a conflict could not be ended on the sea or [by] sea-power alone. It could be ended only by great battles on the Continent. We must be prepared to put armies of millions in the field and maintain them for several years.

Thus the field marshal blew away the ‘all over by Christmas’ illusions that even many senior army officers cherished. Of course, it took time for this to sink in, but the singularity of Kitchener’s views at this vital moment mark out his historical importance. The Foreign Secretary, hearing the field marshal’s assessment that the war would go on for at least three years, disagreed: ‘That seemed to most of us unlikely, if not incredible.’ That same minister, clearly regarding Kitchener as intellectually limited, later wrote that this remarkable foresight came ‘by some flash of instinct, rather than by reasoning’, since Kitchener did not predict trench warfare.

There were many reasons why Kitchener may have briefed the cabinet in the way he did, but it seems clear that he was very conscious of Britain’s relative importance in the Allied pecking order. He understood the same realities that Marlborough and Wellington had done: an expeditionary corps that formed a small part of a combined army (as was the case with the BEF) would come under someone else’s command and gain London limited political leverage. In an age of democracy, however, the deaths of thousands of British troops on French orders or their retreat because the Allies on both of their flanks had fallen back (as happened during the opening weeks of the war) would be all the harder for a British government to justify. He did not doubt victory, and he wanted Britain to have the largest possible say in defining a post-war order.

The consequences of Kitchener’s strategy were enormous, and began with an urgent drive to recruit a million new soldiers. Initially, the War Secretary aimed to take the army up to 57 divisions (there were 18,000 men in a British infantry division at the outbreak of war), but by mid-1915 he would plan for 70, and the requirement for new recruits would reach 3 million. A magazine picture of the field marshal pointing at the reader and commanding ‘Join Your Country’s Army!’ was pressed into use as history’s most celebrated recruiting poster. Later, when volunteers became more reluctant, an official poster carried the warning that conscription would become necessary if too few men volunteered, as indeed eventually happened.

In August 1914, however, the cabinet resolved that conscription was politically unacceptable. Churchill later differed from the collegial position, arguing of these early meetings, ‘It is my belief that had Kitchener proceeded to demand universal national service . . . his request would have been acceded to.’ Patriotism provided the drive instead, as ‘Kitchener armies’ were recruited to boost the army towards its target of seventy divisions by 1916. This degree of national mobilisation was so unprecedented and enormous in its implications that the precise means of raising millions of recruits can be set to one side for a moment. Kitchener’s first biographer noted, ‘It implied the calling of vast armaments into being, the unlearning of a stereotyped national tradition, the acceptance of a radically novel conception of the whole position and mission of England in the world.’

Kitchener brought Britain into the age of total war. By the time hostilities ended, almost one-quarter of the adult male population, 5.7 million men, would have served in the British Army. It can be argued that some Continental powers had already reached this degree of mobilisation by a series of steps beginning with the French conscription laws of 1794, proceeding through the vast campaigns of Napoleon to Bismarck and his militarisation of Germany. But Britain was the world’s most powerful nation, and its abandonment of a centuries-old concept that its army should be small, professional and comprise volunteers was of enormous historical importance.

Obviously, expanding an organisation severalfold in a matter of months was bound to involve all manner of cock-ups and chaos. During one day in September 1914, as the response to Kitchener’s call reached its peak, the army had to enlist as many men (over 30,000) as it had during the entire year of 1913. Many of these recruits wore their civilian clothes for weeks and drilled with broomsticks.

Kitchener knew that good professional officers and NCOs would be needed to train these great new armies, so he kept back thousands of soldiers whom other generals were desperate to send to the front. This caused a serious rift between him and some fellow senior officers who, even late in 1914, thought the field marshal’s planned seventy-division army ridiculous. When Churchill visited the front he heard complaints about the policy everywhere he went, but later reflected admiration for ‘Lord Kitchener’s commanding foresight and wisdom in resisting the temptation to meet the famine of the moment by devouring the seed corn of the future’.

Despite holding back experienced soldiers from training establishments, Kitchener faced a critical officer shortage. He excavated from retirement many crusty old warriors in their sixties and seventies quite ignorant of what a European war might require — the army called them ‘dugouts’. One twenty-seven-year-old captain noted that his dugout commander was ‘quite useless . . . I really ran the brigade and they all knew it.’ This ambitious officer was the young Bernard Montgomery.

Equipping the army posed enormous problems, too. By May 1915 the War Office had ordered 27,000 machine-guns, but eventually it gave up with numbers and simply told Vickers it would buy every gun they could make. Kitchener invited the head of America’s Bethlehem Steel Corporation to London and ordered a million shells and as many rifles as he could make. The Secretary of War was even more pessimistic in his conversations with the American magnate than he had been with the cabinet, arguing that Britain needed to stock up for five years of war.

At times, Kitchener’s old faults undoubtedly hindered this process. He jumped to the conclusion that the Territorial Army was useless and it took others months to change his mind, holding back the committal of substantial reserves to the war. He was also, on one key point at least — the commitment of British troops to the disastrous Gallipoli operation against the Turks — open to accusations of being a poor strategist. Kitchener’s old inability to delegate produced all manner of hold-ups and confusion at the War Office. The field marshal often refused to share vital information with his officials there, and even with the cabinet, regarding almost every detail as secret. In this respect he epitomised the spirit of the times, because during the run-up to 1914 the British government had finally formulated its concept of official secrecy.

These shortcomings contributed to a political crisis over the supply of shells in 1915, with Kitchener being relieved of authority for munitions production. The main beneficiary from this cabinet punch-up was none other than David Lloyd George, whose ‘pro-Boer’ attacks on Kitchener’s tactics in South Africa had proven so irksome to the War Office many years earlier. During cabinet-room sparring, the Welsh MP (who was Chancellor of the Exchequer as well as the new Minister for Munitions) evidently ran verbal rings around the field marshal. The Prime Minister wrote that in these spats Lloyd George let fly with ‘some of the most injurious and wounding innuendos, which K will be more than human to forget’. Kitchener, always the closed book, never really said what he thought of Lloyd George, describing him only as a ‘peppery fellow’.

In general, Kitchener was loath to respond publicly to press or parliamentary criticism, believing that this would turn him into a politician, a species into which he certainly did not wish to evolve. On 2 June 1916, just one month before the Somme offensive, however, he tried to answer MPs’ concerns about the colossal casualties on the Western Front and the overall course of the war. K went to the Palace of Westminster to brief 200 members. He insisted that this should be confidential, but minutes were taken, and they form one of the few lengthy accounts, in his own words, of what the Secretary of War was trying to do during 1914-16. (One of his biographers suggests that this was one of only four occasions when he spoke publicly during twenty-two months in the cabinet.)

‘I feel sure Members must realise that my previous work in life has naturally not been of a kind to make me into a ready debater, nor to prepare me for the twists and turns of argument,’ he said, excusing his refusal to appear in open session at Westminster. He talked about the enormous mobilisation and admitted it had been a ‘gigantic experiment’. ‘I was convinced that . . . we had to produce a new army sufficiently large to count in a European war,’ Kitchener then told the hushed MPs. ‘I had rough-hewn in my mind the idea of creating such a force as would enable us continuously to reinforce our troops in the field by fresh divisions, and thus assist our Allies at the time when they were beginning to feel the strain of the war with its attendant casualties.’

This notion, that British forces should be on the rise at the decisive period of the war, was a vital aspect of Kitchener’s plans — and it is worth underlining that he said this in the summer of 1916 when few others had any idea whether the conflict would go on for one more year or ten. There were many implications in this build-up, as he hinted to the MPs: ‘We planned to work on the upgrade while our Allies’ forces decreased, so that at the conclusive period of the war we should have the maximum trained fighting army this country could produce.’ The timetable was therefore designed at one and the same time to maximise Britain’s killing power against the Germans and its political clout vis-a-vis France. Kitchener left the meeting satisfied that he had defused some of the discontent that just a few days earlier had produced an unsuccessful censure motion against him in the Commons. He then prepared to set off on a trip to Russia, where Britain’s allies were buckling under the pressure of war.

On 5 June, HMS Hampshire, the cruiser carrying the Secretary of War, set sail from Scapa Flow. There were dangers for the fleet, even this close to home, because German submarines had been trying to penetrate British defences. Having surveyed the Royal Navy’s usual deployments, the U-boats laid mines. It was the Secretary of War’s misfortune that the Hampshire struck one just a few hours into its journey. The cruiser went down in minutes and Kitchener drowned as she sank. There was public grief, with many a diarist recording in the sonorous tones of that era the weeping of East End market girls or the grim expressions in their officers’ mess. There were tributes aplenty from the field marshal’s contemporaries, but I prefer that of A.J.P Taylor, perhaps the greatest historian of the twentieth century, who called Kitchener ‘the only British military idol of the First World War’. Certainly, in the public’s eyes, he was a soldier without peer.

Kitchener’s achievements in breaking the Mahdist state in Sudan and crushing the Boer insurgency were of historical importance, but secondary. It was by the creation of a vast army in 1914 that he left his mark. It can be argued — according to one’s prejudices — that he summoned an entire generation of British youth to their doom or that he allowed his country to decide the outcome of the First World War. Either way, it is hard to claim that what he did was insignificant.

The field marshal’s entry in the Dictionary of National Biography argues that his mobilisation ‘not only saved the British empire from destruction, but Europe from German domination’. Many such claims, made in the rosy glow of self-satisfied nationalism, do not stand up to scrutiny, particularly when you examine what a country’s enemies were saying. It is therefore worth quoting the views of General Erich von Ludendorff, the man who was at the helm of Germany’s war strategy: ‘Through [Kitchener’s] genius alone England developed side by side with France into an opponent capable of meeting Germany on even terms, whereby the position on the front in France in 1915 was so seriously changed to Germany’s disadvantage.’

In evaluating the 20th Century British war machine it is often hard to estimate the value of individuals, however eminent. But it is very hard to credit anyone other than Kitchener with responsibility for Britain’s vast national mobilisation in August 1914. The field marshal’s ‘long war’ views put him at odds with everyone else in the Cabinet and, indeed the War Office. It is largely due to this foresight, as General Ludendorff acknowledged, that Britain and France did not buckle in 1915. In terms of alternative history, a German victory in that year would have opened up some mind — boggling possibilities, not least of checking the rise of Hitler or averting the Russian Revolution. The old empires might not have lasted indefinitely if the war had ended in 1915, but Europe and the world would undoubtedly have developed very differently.

Kitchener was not a pleasant man, and his anti-intellectualism and prejudice against elected leaders make him rather suspect to our generation. At the dawning of an era of total war and industrialised slaughter, he was, however, quite indispensable to his country.