Opération Daguet (Operation Brocket – young stag) was the codename for French operations during the 1991 Gulf War. The conflict was between Iraq and a coalition force of approximately 30 nations led by the United States and mandated by the United Nations in order to liberate Kuwait.

Operations Desert Shield, Granby and Daguet were the separate codenames of the American, British and French operations in Saudi Arabia.

France contributed 14,000 men, as part of Opération Daguet, under Lieutenant General Michel Roquejoffre, who commanded the French Rapid Reaction Force. The French force comprised Foreign Legion, Marine infantry, helicopter and armoured car units. The main formation was the 6th Light Armoured Division, with forty AMX-10C AFVs under Brigadier General Mouscardes. It should be noted that French divisions are smaller than their NATO counterparts and are typically reinforced brigades. However, the 6th Division was augmented with reinforcements that included the 4th Dragoon Regiment, a tank unit equipped with forty-four AMX-30B2 tanks, from the French 10th Armoured Division. Although the AMX-30B2 model was old and due to be replaced by the Leclerc, it was more than able to deal with most Iraqi tanks.

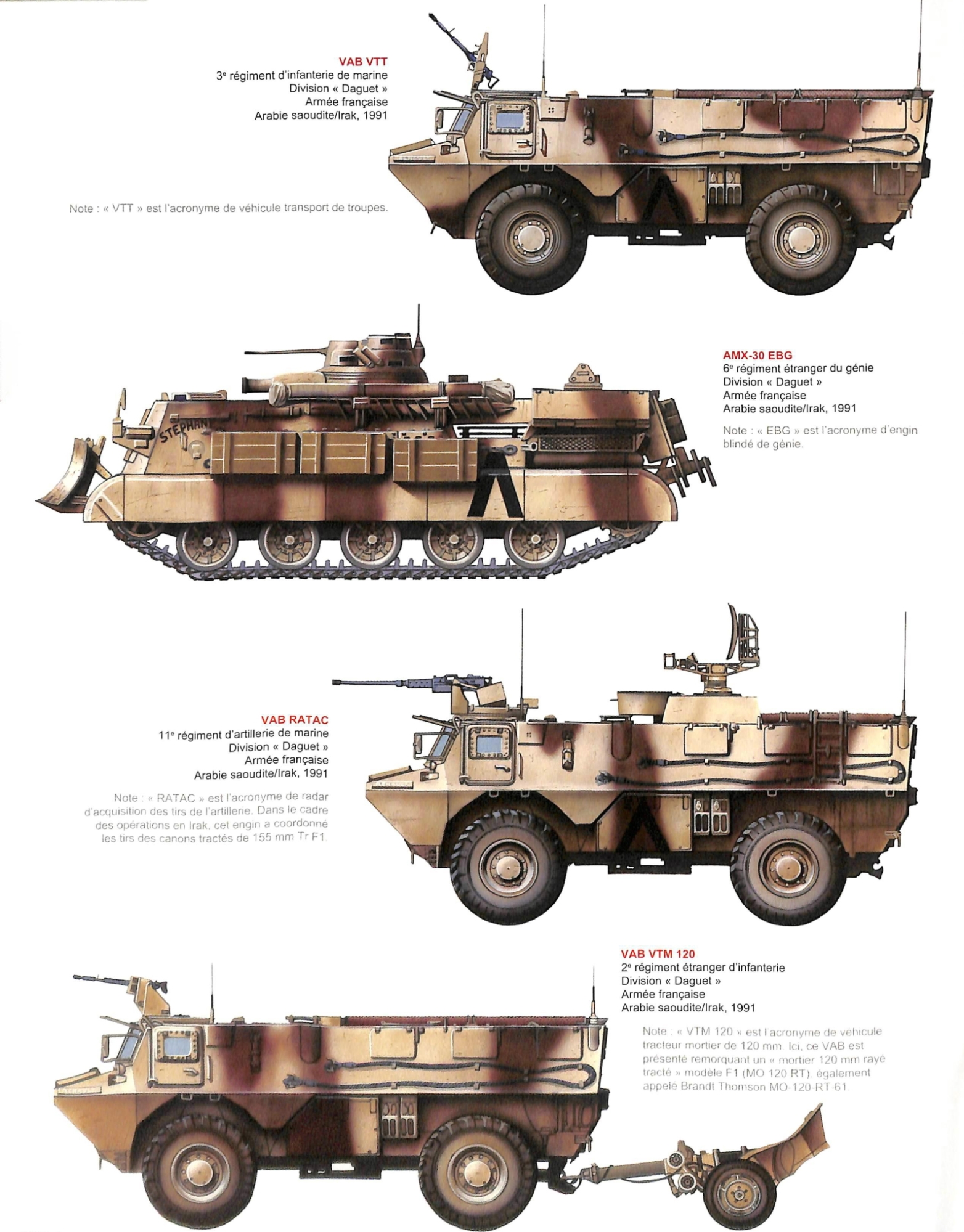

The French participation in the Gulf War saw the deployment of the 6e Division Légère Blindée (“6th Light Armored Division”), referred to for the duration of the conflict as the Division Daguet. Most of its armored component was provided by the AMX-10RCs of the cavalry reconnaissance regiments, but a heavy armored unit, the 4e Régiment de Dragons (“4th Dragoon Regiment”) was also sent to the region with a complement of 44 AMX-30B2s. Experimentally, a new regimental organisational structure was used, with three squadrons of thirteen tanks, a command tank and six reserve vehicles, instead of the then normal strength of 52 units. Also six older AMX-30Bs were deployed, fitted with Soviet mine rollers provided by Germany from East German stocks, and named AMX 30 Demin. The vehicles were all manned by professional crews, without conscripts. The Daguet Division was positioned to the West of Coalition forces, to protect the right flank of the U. S. XVIII Airborne Corps. This disposition gave the French commander greater autonomy, and also lessened the likelihood of encountering Iraqi T-72s, which were superior both to the AMX-10RCs and the AMX-30B2s. With the beginning of the ground offensive of 24 February 1991, French forces moved to attack its first target, “Objective Rochambeau”, that was defended by a brigade from the Iraqi 45th Infantry Division. A raid by Gazelle helicopters paved the way for an attack by the 4e Régiment de Dragons. Demoralized by heavy coalition bombardments, the Iraqi defenders rapidly surrendered. The following day, the 4e Dragons moved on to their next objective, “Chambord”, where they reported destroying ten tanks, three BMPs, fifteen trucks and five mortars with the assistance of USAF A-10s, and capturing numerous prisoners. The final objective was the As-Salman air base (“Objective White”), that was reported captured by 18:15, after a multi-pronged attack, with the 4e Dragons attacking from the South. In all, the AMX-30s fired 270 main gun rounds in anger.

The 100-hour Ground War

On 24 February, when ground operations started in earnest, coalition forces were poised along a line that stretched from the Persian Gulf westward three hundred miles into the desert. The XVIII Airborne Corps, under General Luck, held the left, or western, flank and consisted of the 82d Airborne Division, the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault), the 24th Infantry Division (Mechanized), the French 6th Light Armored Division, the 3d Armored Cavalry Regiment, and the 12th and 18th Aviation Brigades. The VII Corps was deployed to the right of the XVIII Airborne Corps and consisted of the 1st Infantry Division (Mechanized), the 1st Cavalry Division (Armored), the 1st and 3d Armored Divisions, the British 1st Armoured Division, the 2d Armored Cavalry Regiment, and the 11th Aviation Brigade. These two corps covered about two-thirds of the line occupied by the larger multinational force.

Three commands held the eastern one-third of the front. Joint Forces Command-North, made up of formations from Egypt, Syria, and Saudi Arabia and led by His Royal Highness Lt. Gen. Prince Khalid ibn Sultan, held the portion of the line east of the VII Corps. To the right of these allied forces stood Lt. Gen. Walter E. Boomer’s I Marine Expeditionary Force, which had the 1st (Tiger) Brigade of the Army’s 2d Armored Division as well as the 1st and 2d Marine Divisions. Joint Forces Command-East on the extreme right, or eastern, flank anchored the line at the Persian Gulf. This organization consisted of units from all six member states of the Gulf Cooperation Council. Like Joint Forces Command-North, it was under General Khalid’s command.

Day One: 24 February 1991

After thirty-eight days of continuous air attacks on targets in Iraq and Kuwait, President Bush directed the U. S. Central Command to proceed with the ground offensive. General Schwarzkopf unleashed all-out attacks against Iraqi forces very early on 24 February at three points along the coalition line. In the far west, the French 6th Light Armored Division and the 101st Airborne Division started the massive western envelopment with a ground assault to secure the coalition left flank and an air assault to establish forward support bases deep in Iraqi territory. (Map 4) In the approximate center of the coalition line, along the Wadi al Batin, Maj. Gen. John H. Tilelli Jr.’s 1st Cavalry Division attacked north into a concentration of Iraqi divisions whose commanders remained convinced that the coalition would use that and several other wadis as avenues of attack. In the east, two Marine divisions, with the Army’s Tiger Brigade and coalition forces under Saudi command, attacked north into Kuwait. Faced with major attacks from three widely separated points, the Iraqi command had to begin its ground defense of Kuwait and the homeland by dispersing its combat power and logistical capability.

The attack began from the XVIII Airborne Corps’ sector along the left flank. At 0100, Brig. Gen. Bernard Janvier sent scouts from his French 6th Light Armored Division into Iraq on the extreme western end of General Luck’s line. Three hours later, the French main body attacked during a light rain. Their objective was As Salman, little more than a crossroads with an airfield about ninety miles inside Iraq. Reinforced by the 2d Brigade, 82d Airborne Division, the French crossed the border unopposed and raced north into the darkness.

Before the French reached As Salman, they found some very surprised outposts of the Iraqi 45th Infantry Division. General Janvier immediately sent his missile-armed Gazelle attack helicopters against the dug-in enemy tanks and bunkers. Late intelligence reports had assessed the 45th as only about 50 percent effective after weeks of intensive coalition air attacks and psychological operations, an assessment soon confirmed by its feeble resistance. After a brief battle that cost them two dead and twenty-five wounded, the French held twenty-five hundred prisoners and controlled the enemy division area, now renamed Rochambeau. Janvier pushed his troops on to As Salman, which they took without opposition and designated Objective White. The French consolidated White and waited for an Iraqi counterattack that never came. The coalition’s left flank was secure. Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. James H. Johnson Jr.’s 82d Airborne Division carried out a mission that belied its airborne designation. While the division’s 2d Brigade moved with the French, its two remaining brigades, the 1st and 3d, trailed the advance and cleared a two-lane highway into southern Iraq as the main supply route for the troops, equipment, and supplies supporting the advance north.

The XVIII Airborne Corps’ main attack, led by Maj. Gen. J. H. Binford Peay III’s 101st Airborne Division, was scheduled for 0500; but fog over the objective forced a delay. While the weather posed problems for aviation and ground units, it did not abate direct-support fire missions. Corps artillery and rocket launchers poured fire on objectives and approach routes. At 0705, Peay received the word to attack. Screened by Apache and Cobra attack helicopters, sixty Black Hawk and forty Chinook choppers of the XVIII Airborne Corps’ 18th Aviation Brigade began lifting the 1st Brigade into Iraq. The initial objective was Forward Operating Base (FOB) cobra, a point some one hundred ten miles into Iraq. A total of three hundred helicopters ferried the 101st’s troops and equipment into the objective area in one of the largest helicopter-borne operations in military history.

Wherever Peay’s troops went during those initial attacks, they achieved tactical surprise over the scattered and disorganized foe. By midafternoon, they had a fast-growing group of stunned prisoners in custody and were expanding FOB cobra into a major refueling point twenty miles across to support subsequent operations. Heavy CH-47 Chinook helicopters lifted artillery pieces and other weapons into cobra, as well as fueling equipment and building materials to create a major base. From the Saudi border, XVIII Corps support command units drove seven hundred high-speed support vehicles north with the fuel, ammunition, and supplies to support a drive to the Euphrates River.

As soon as the 101st secured cobra and refueled the choppers, it continued its jump north. By the evening of the twenty-fourth, its units had cut Highway 8, about one hundred seventy miles into Iraq. Peay’s troops had now closed the first of several roads connecting Iraqi forces in Kuwait with Baghdad. Spearhead units were advancing much faster than expected. To keep the momentum of the corps intact, General Luck gave subordinate commanders wider freedom of movement. He became their logistics manager, adding assets at key times and places to maintain the advance. But speed caused problems for combat support elements. Tanks that could move up to fifty miles per hour were moving outside the support fans of artillery batteries that could displace at only twenty-five to thirty miles per hour. Luck responded by leapfrogging his artillery battalions and supply elements, a solution that cut down on fire support since only half the pieces could fire while the other half raced forward. As long as Iraqi opposition remained weak, the risk was acceptable.

In the XVIII Corps’ mission of envelopment, the 24th Infantry Division had the central role of blocking the Euphrates River valley to prevent the northward escape of Iraqi forces in Kuwait and then attacking east in coordination with the VII Corps to defeat the armor-heavy divisions of the Republican Guard Forces Command. Maj. Gen. Barry R. McCaffrey’s division had come to the theater better prepared for combat in the desert than any other in Army Central Command. Designated a Rapid Deployment Force division a decade earlier, the 24th combined the usual mechanized infantry division components-an aviation brigade and three ground maneuver brigades plus combat support units-with extensive desert training and desert-oriented medical and water-purification equipment.

When the attack began, the 24th was as large as a World War I division, with twenty-five thousand soldiers in thirty-four battalions. Its 241 Abrams tanks and 221 Bradley fighting vehicles provided the necessary armor punch to penetrate Republican Guard divisions. But with ninety-four helicopters and over sixty-five hundred wheeled and thirteen hundred other tracked vehicles-including seventy-two self-propelled artillery pieces and nine multiple rocket launchers-the division had given away nothing in mobility and firepower.

General McCaffrey began his division attack at 1500 with three subordinate units on line: the 197th Infantry Brigade on the left, the 1st Infantry Brigade in the center, and the 2d Infantry Brigade on the right. Six hours before the main attack, the 2d Squadron, 4th Cavalry, had pushed across the border and scouted north along the two combat trails toward the Iraqi lines. The reconnaissance turned up little evidence of the enemy, and the rapid progress of the division verified the scouts’ reports. McCaffrey’s brigades pushed about fifty miles into Iraq, virtually at will, and reached a position a little short of FOB cobra in the 101st Airborne Division’s sector.

In their movement across the line of departure and whenever not engaging enemy forces, battalions of the 24th Infantry Division generally moved in “battle box” formation. With a cavalry troop screening five to ten miles to the front, four companies, or multiplatoon task forces, dispersed to form corner positions. Heavier units of the battalion, whether composed of tanks or Bradleys, occupied one or both of the front corners. One company or smaller units advanced outside the box to provide flank security. The battalion commander placed inside the box the vehicles carrying ammunition, fuel, and water needed to continue the advance in jumps of about forty miles. The box covered a front of about four to five miles and extended about fifteen to twenty miles front to rear.

Following a screen of cavalry and a spearhead of the 1st and 4th Battalions, 64th Armor, McCaffrey’s division continued north, maintaining a speed of twenty-five to thirty miles per hour. In the flat terrain, the 24th kept on course with the aid of long-range electronic navigation, a satellite-reading triangulation system in use for years before Desert storm. Night did not stop the division, thanks to more recently developed image-enhancement scopes and goggles and infrared- and thermal-imaging systems sensitive to personnel and vehicle heat signatures. Around midnight, McCaffrey stopped his brigades on a line about seventy-five miles inside Iraq. Like the rest of the XVIII Airborne Corps, the 24th Division had established positions deep inside Iraq against surprisingly light opposition.

The VII Corps, consisting mainly of the 1st Infantry Division, the 1st and 3d Armored Divisions, the 1st Cavalry Division, the British 1st Armoured Division and the 2d Armored Cavalry Regiment, had the mission of finding, attacking, and destroying the heart of Saddam Hussein’s ground forces, the armor-heavy Republican Guard. In preparation for that, Central Command had built up General Franks’ organization until it resembled a mini army more than a traditional corps. The “Jayhawk” corps of World War II fame numbered more than one hundred forty-two thousand soldiers compared with Luck’s one hundred sixteen thousand. To keep his troops moving and fighting, General Franks had more than forty-eight thousand five hundred vehicles and aircraft, including 1,587 tanks, 1,502 Bradleys and armored personnel carriers, 669 artillery pieces, and 223 attack helicopters. To provide a sense of the logistical challenge to keep such a phalanx supplied, for every day of offensive operations the corps needed 5.6 million gallons of fuel, 3.3 million gallons of water, and 6,075 tons of ammunition.

The plan of advance for the VII Corps paralleled that of Luck’s corps to the west: a thrust north into Iraq, a massive turn to the right, and then an assault to the east into Kuwait. Because Franks’ sector lay east of Luck’s-in effect closer to the hub of the envelopment wheel-the VII Corps had to cover less distance than the XVIII Airborne Corps. But intelligence reports and probing attacks into Iraqi territory in mid-February had shown that the VII Corps faced a denser concentration of enemy units than did the XVIII Corps farther west. Once the turn to the right was complete, both corps would coordinate their attacks east so as to trap Republican Guard divisions between them and then press the offensive along their wide path of advance until Iraq’s elite units either surrendered, retreated, or were destroyed.

General Schwarzkopf originally had planned the VII Corps attack for 25 February, but the XVIII Airborne Corps advanced so quickly against such weak opposition that he moved up his armor attack by fourteen hours. Within his own sector, Franks planned a feint and envelopment much like the larger overall strategy. On the VII Corps’ right, along the Wadi al Batin, the 1st Cavalry Division would make a strong but limited attack directly to its front. While Iraqi units reinforced against the 1st Cavalry, Franks would send two divisions through sand berms and mines on the corps’ right and two more divisions on an “end around” into Iraq on the corps’ left.

On 24 February, the 1st Cavalry Division crossed the line of departure and hit the Iraqi 27th Infantry Division. That was not their first meeting. General Tilelli’s division had actually been probing the Iraqi defenses for some time. As these limited thrusts continued in the area that became known as the Ruqi Pocket, Tilelli’s men found and destroyed elements of five Iraqi divisions, evidence that the 1st succeeded in its theater reserve mission of drawing and holding enemy units.

The main VII Corps attack, coming from farther west, caught the defenders by surprise. At 0538, Franks sent Maj. Gen. Thomas G. Rhame’s 1st Infantry Division forward. The division plowed through the berms and hit trenches full of enemy soldiers. Once astride the trench lines, it turned the plow blades of its tanks and combat earthmovers along the Iraqi defenses and, covered by fire from Bradley crews, began to fill them in. The 1st Division neutralized ten miles of Iraqi lines this way, killing or capturing all of the defenders without losing one soldier, and proceeded to cut twenty-four safe lanes through the minefields for passage of the British 1st Armoured Division. On the far left of the corps sector and at the same time, the 2d ACR swept around the Iraqi obstacles and led 1st and 3d Armored Divisions into enemy territory.

The two armored units moved rapidly toward their objective, the town of Al Busayyah, site of a major logistical base about eighty miles into Iraq. The 1st Armored Division on the left along the XVIII Airborne Corps’ boundary and the 3d Armored Division on its right moved in compressed wedges fifteen miles wide and thirty miles deep. Screened by cavalry squadrons, the divisions deployed tank brigades in huge triangles, with artillery battalions between flank brigades and support elements in nearly one thousand vehicles trailing the artillery.

Badly mauled by air attacks before the ground operation and surprised by Franks’ envelopment, Iraqi forces offered little resistance. The 1st Infantry Division destroyed two T-55 tanks and five armored personnel carriers in the first hour and began taking prisoners immediately. Farther west, the 1st and 3d Armored Divisions quickly overran several small infantry and armored outposts. Concerned that his two armored units were too dispersed from the 1st Infantry Division for mutual reinforcement, Franks halted the advance with both armored elements on the left only twenty miles into Iraq. For the day, the VII Corps rounded up about thirteen hundred of the enemy.

In the east, the U. S. Marine Central Command (MARCENT) began its attack at 0400. General Boomer’s I MEF aimed directly at its ultimate objective, Kuwait City. The Tiger Brigade, 2d Armored Division, and the 1st and 2d Marine Divisions did not have as far to go to reach their objective as did Army units to the west-Kuwait City lay between thirty-five and fifty miles to the northeast, depending on the border-crossing point-but they faced more elaborate defense lines and a tighter enemy concentration. The 1st Marine Division led from a position in the vicinity of the elbow of the southern Kuwaiti border and immediately began breaching berms and rows of antitank and antipersonnel mines and several lines of concertina wire. The unit did not have Abrams tanks, but its M60A3 Patton tanks and TOW-equipped high mobility multipurpose wheeled vehicles, supported by heavy artillery, proved sufficient against Iraqi T-55 and T-62 tanks. After the marines destroyed two tanks in only a few minutes, three thousand Iraqis surrendered.

At 0530, the 2d Marine Division, with Col. John B. Sylvester’s Tiger Brigade on its west flank, attacked in the western part of the MARCENT sector. The Army armored brigade, equipped with M1A1 Abrams tanks, gave the marines enough firepower to defeat any armored units the Iraqis put between Boomer’s force and Kuwait City. The first opposition came from a berm line and two mine belts. Marine M60A1 tanks with bulldozer blades quickly breached the berm, but the mine belts required more time and sophisticated equipment. Marine engineers used mine-clearing line charges and M60A1 tanks with forked mine plows to clear six lanes in the division center, between the Umm Qudayr and Al Wafrah oil fields. By late afternoon, the Tiger Brigade had passed the mine belts. As soon as other units passed through the safe lanes, the 2d Marine Division repositioned to continue the advance north, with regiments on the right and in the center and the Tiger Brigade on the left tying in with the coalition forces.

Moving ahead a short distance to a major east-west highway by the end of the day, the 2d Marine Division captured intact the Iraqi 9th Tank Battalion with thirty-five T-55 tanks and more than five thousand men. Already, on the first day of ground operations, the number of captives had become a problem in the marine sector. After a fight for Al Jaber Airfield, during which the 1st Marine Division destroyed twenty-one tanks, another three thousand prisoners were seized. By the end of the day, the I Marine Expeditionary Force had worked its way about twenty miles into Kuwait and taken nearly ten thousand Iraqi prisoners.