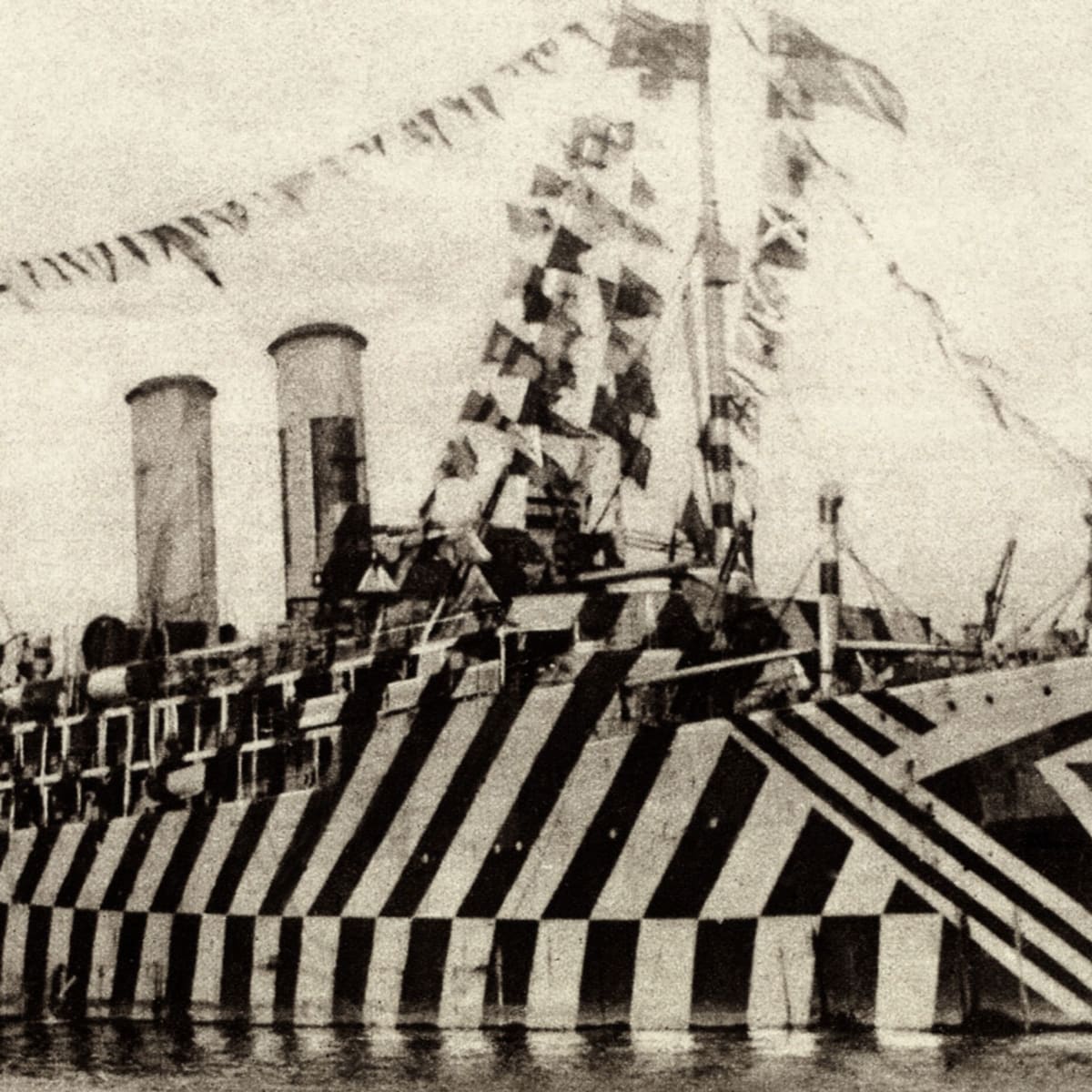

‘dazzle’ camouflage

The development of the ironclad increased the size and cost of ships. At the same time, improved armaments increased the range at which actions were fought and reduced the scope for capture, making sinking a more likely outcome of an action and thus making it increasingly difficult and expensive to replace losses. But losses must be accepted if control of the seas is to be gained and maintained, as it must be if commerce is to flow unhindered. However, the official history of the First World War describes how

by a strange misreading of history, an idea had grown up that [a fleet’s] primary function is to seek out and destroy the enemy’s main fleet. This view, being literary rather than historical, was nowhere adopted with more unction than in Germany, where there was no naval tradition to test its accuracy.

On the one occasion the German Battle Fleet did enter the North Sea to fulfil its aim, it achieved a marginal tactical victory over the British (in simple terms of losses) at the Battle of Jutland, but there can be no doubt as to the strategic result of the battle. The British did not deceive the Germans but simply faced them down, and the German Battle Fleet spent the remainder of the war sitting idly in port while the British naval blockade helped squeeze Germany to ultimate defeat. However, British nervousness of the German Battle Fleet forced her to denude some other vital positions of destroyers, such as Dover. Thus the Dover patrol had to rely on bluff to prevent German naval forces operating from the Belgian ports from interfering with the vital cross-Channel traffic.

Meanwhile, Britain herself came perilously close to being squeezed to defeat by Germany’s commerce raiders and U-boats during both world wars. An early effort to counter this threat was camouflage paint schemes. Transport and cargo ships were painted neutral blue, grey or sea-green in the hope of avoiding detection for as long as possible. Warships, on the other hand, are not looking to avoid contact but instead require every fighting advantage they can muster, particularly in the early stages of an action. One result was a proposal by an eminent Scottish zoologist, John Graham Kerr, whose study of marine vertebrates suggested that odd patterns of white and grey might help make ships harder to identify. Although the Admiralty circulated his suggestions as early as October 1914, it left responsibility to individual captains and was later shelved. It took further prompting from another painter, P. Tudor Hart, and an RNVR lieutenant, Norman Wilkinson (a marine painter and poster designer who had served in the Dardanelles campaign) who wrote to the Admiralty on 27 April 1917, to create what was known as ‘dazzle’ camouflage. In poor visibility, at long range or at high speed, this served to hinder an observer’s ability to identify a vessel accurately, perhaps long enough to give it a precious advantage. It also made judging the vessel’s speed more difficult – very important when trying to fire at long range. Gunnery officers and submarine captains had to ‘track’ moving ships on calibrated range-finders and periscopes, but the pattern distorted the image and made it harder to secure a hit. Refinements of the same technique included false bow waves to give the impression of greater speed, false waterlines which were designed to inhibit accurate estimation of range, and painting the upper works a lighter colour to blend them with the sky. The effectiveness of the technique was questionable but it raised morale and was therefore retained, mainly for merchant shipping. Nevertheless, during the Second World War the Admiralty Research and Development Section employed the naturalist and artist Peter Scott to develop further patterns.

The vulnerability of shipping to aircraft, demonstrated among other instances by the destruction of HMS Repulse and Prince of Wales by the Japanese on 11 December 1941, made it essential to camouflage ships from the air. On the open ocean, ships could not avoid being spotted by aircraft in the vicinity. For example, a US aircraft north of Guadalcanal flying at 18,000 feet spotted five destroyers belonging to Rear-Admiral Tanaka’s ‘Tokyo Express’ at a distance of eight to ten miles, and sighting fast-moving warships at greater ranges was not unheard of in good conditions. Attempts were made to design patterns that gave some protection from aerial attack, but these were seldom effective, at least while a ship was at sea. Eventually, technical developments such as radar and acoustic torpedoes made dazzle patterns largely redundant, but they continued in use throughout the Second World War.

If a ship was inshore, by its very nature it might be found if aircraft looked in the bays, rivers and ports. Paint might go some way to protect it in such circumstances, blending it with its surroundings just long enough to put a bomb aimer off, but a photo interpreter could probably identify its class precisely and thus reveal its speed, firepower and cargo capacity. Nets and, where appropriate, cut vegetation might help to make the tell-tale shape of a ship blend in with the shoreline and barges and floating material could be used to break up the characteristic shape of bow and stern.

The German auxiliary cruiser Atlantis (HSK 2), known to the Kriegsmarine as Schiff 16 and to the Royal Navy as Raider-C, was a converted German Hilfskreuzer (auxiliary cruiser), or merchant or commerce raider of the Kriegsmarine, which, in World War II, travelled more than 161,000 km (100,000 mi) in 602 days, and sank or captured 22 ships with a combined tonnage of 144,384. Atlantis was commanded by Kapitän zur See Bernhard Rogge, who received the Oak Leaves to the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross. She was sunk on 22 November 1941 by the British cruiser HMS Devonshire.

Another early measure adopted to counter U-boats was the arming of merchant ships in 1915, which was followed by the creation of Q-ships. These were merchant ships armed with concealed guns and torpedoes manned by naval crews, designed to lure the U-boats – which preferred to destroy merchant vessels by gunfire – to a position where they themselves could be destroyed. The Q-ships were eventually credited with eleven U-boat kills out of a total for the First World War of 192. During both wars the Germans operated similar ships as merchant raiders. Perhaps the most famous example was the Atlantis, commanded by Kapitän zur See Bernard Rogge during the Second World War, one of nine such ships which sank 850,000 tons of Allied shipping and kept the Allies busy for three and a half years. The Atlantis logged over 100,000 miles in 622 days at sea and accounted for twenty-two Allied freighters, making her the most successful surface raider of the war. In the course of her wanderings she pretended variously to be the Krim (Russian), the Kasii Maru (Japanese), the Abbekerk (Dutch) and the Antenor (British).

Carrying huge stocks of fuel and food, Atlantis mounted behind collapsable bulkheads an armament of one 75mm and six 150mm guns and six light anti-aircraft guns, plus four torpedo tubes, mines and a Heinkel He-114 seaplane for reconnaissance. She had a dummy stack and cargo booms and carried a variety of fake foreign uniforms and clothing, male and female, which the crew could use as appropriate. In addition, there was a large supply of paint to change her name and the colour of the superstructure. It is perfectly legal for a ship to operate in this fashion, providing it displays the correct national flag before opening fire, and Rogge adhered strictly to this law, as well as endeavouring whenever possible to pick up survivors, who were treated graciously.

Rogge trained his gunners to shoot out a victim’s radio equipment first, which would allow the remainder of his operation to take place in slow time. None the less, a stream of QQQ messages (‘I am being attacked by a disguised merchant ship’) eventually helped the Admiralty to track him down. The final clue to Atlantis’s whereabouts in November 1941 was provided by ULTRA intercepts ordering her to resupply submarines south of the Equator. On 22 November a seaplane from HMS Devonshire (sent to nearby Freetown to look for her) sighted a suspicious merchant ship and opened fire while Atlantis was in the process of replenishing U-126. Rogge tried one last desperate trick. He signalled urgently (and indignantly) that he was the Polyphemus, a Dutch ship, then gave the signal RRR: an Allied cipher that an enemy warship was close by. Unbeknown to Rogge, this cipher had recently been changed to four Rs. A new precautionary system introduced by the Admiralty to plot the whereabouts of every single known ocean-going merchantman confirmed Devonshire’s suspicions and when word came from Freetown that this ship could not possibly be Polyphemus, Rogge and his crew were forced to take to the boats. Afraid of lurking U-boats, Devonshire made off, and after a series of extraordinary adventures Rogge and the survivors were eventually picked up by U-boats and returned to Germany.