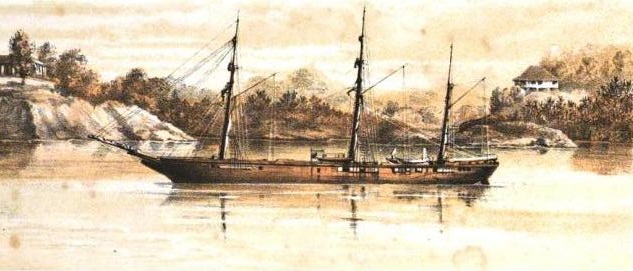

The CSS Alabama in Singapore harbour

The Alabama under sail

Captain Semmes and First Lieutenant Kell on the Alabama, 1863

Vegetius, writing in the fourth century AD, describes how Roman skiffs used for reconnaissance had their sails and rigging dyed Venetian blue

which resembles the ocean waves; the wax used to pay ships’ sides is also dyed. The sailors and marines put on Venetian blue uniforms also, so as to lie hidden with greater ease when scouting by day as by night.

Warfare at sea has obviously been subject to bluff and deception for as long as warfare on land. In 1264, during the long wars with Venice, the Genoese decided to intercept the ‘caravan of the Levant’, an annual convoy that the Venetians sailed to Egypt and Asia. The caravan was an event of great moment. Its dates of departure and return were fixed by strict laws, as were the numbers of men on each vessel and the conduct of the convoy itself. The commanders and captains were chosen by the Great Council and in times of war the Senate pronounced the chiusura del Mare (‘closing of the sea’), a decree that forbade any vessel from leaving the convoy, while arrangements would be made to escort it with war galleys. The Genoese well understood the importance of this convoy to Venice and decided to send Simone Grillo with twenty galleys, two large vessels and a contingent of 3,500 men to intercept it. In reply, the Venetians assembled a force of no fewer than forty-seven galleys under ‘a brave man and wise, and sprung of high lineage’, Andrea Barozzi. This ‘noble captain’ set out for Sicily expecting to intercept the Genoese before they in turn could attack the caravan.

Alas for Barozzi, on this occasion his wisdom failed him. The Genoese were indeed there, but all he found was ‘a boat in which there were men who told him on inquiry that the Genoese galleys had passed four days previously, bound for Syria’. After a hastily assembled council of war, Barozzi set off in a fruitless pursuit and as soon as the news reached Venice orders were given for the immediate departure of the caravan, which had been delayed owing to the supposed presence of the enemy in the Adriatic. Grillo now emerged and put his fleet into position at Durazzo to await the arrival of the caravan, the movements of which he was kept fully informed of by an underwriter of the Great Council (who, the chronicles note with barbed acidity, came from Treviso). When in due course the caravan was intercepted, its commander, Michele Duaro, tried bravado, throwing some chicken coops in front of the Genoese line and bidding them fight the chickens. However, this served no purpose and with no escort of warships the caravan was soon destroyed, as grievous a blow to Venetian prestige as to her material well-being.

Not only does this episode illustrate an early example of deception in naval warfare, but it also shows the importance of commerce to naval strategy. While the principles of warfare and of deception apply equally on land and at sea, there are obviously fundamental differences. While land warfare is fought with units containing thousands of men and hundreds of pieces of equipment, naval warfare is conducted with dozens of units or (more usually) fewer, each of relatively great value. More importantly, it is fought over a vast area, with no natural cover. The size of the ships also makes it hard to conceal or disguise them and their shapes make identification of their nationality and class quite simple, so that deception is difficult – but not impossible. Since it was common in the days of sail to capture enemy shipping rather than to destroy it, it was equally common for foreign-built ships to serve with the navies that had captured them, and therefore not unusual to see them bearing different colours from their country of origin. Over the years many other measures have been adopted to suggest that a ship is not what it appears, giving plenty of scope for tactical deception.

Thomas Cochrane, tenth Earl of Dundonald, was a daring and inspirational leader who was always prepared to use guile combined with forethought and audacity to overcome large odds, in other words a master of deception. He was convinced (and proved) that a single ship correctly handled, preying on coastal shipping and coast defences, could cause the enemy loss and distress out of all proportion to the effort expended. He took great pains over the training and welfare of his men and this paid dividends in their performance. His first command was the 168-ton brig HMS Speedy, which he operated off the Spanish coast in 1800. Knowing the Spaniards would soon come to recognize his vessel for an enemy, he repainted it to resemble the neutral Dutch ship Clomer, which had been trading in the area for some time. He also recruited a Danish speaker whom he provided with a Danish uniform. Towards the end of December he gave chase to what appeared to be a heavily laden, unarmed merchantman, only to discover as he drew near that he too had been duped. It was a Spanish frigate with some 200 men and heavy guns, which now put down a boat. He ordered below everyone who looked British, and set his ‘Dane’ to tell the Spaniards they were neutrals. When this failed to put them off, one of his men hoisted a yellow flag (quarantine) to the foretop and the ‘Dane’ said they were just out of Algiers. The Spanish knew that Algiers was suffering from an outbreak of bubonic plague and quickly returned whence they had come.

Three months later Cochrane was chased by an enemy frigate, which gained on him throughout the day and was guided at night by the faint glimmer of light from the little brig. But as they drew near towards daybreak, the enemy frigate found it had been chasing a tub with a lantern in it and the brig was nowhere to be seen. Cochrane later used the same ruse again. Commanding the frigate HMS Pallas in March 1805, he was chased by three French 74-gun ships of the line off the Azores. After conducting a brilliant manœuvre to run back on them, he was pursued for the rest of the day and all night, but when they closed in for the kill all they found was a ballasted cask with a lantern made fast to it.

Captain Raphael Semmes and the Confederate cruiser CSS Alabama forged a formidable reputation as a commerce raider. The Alabama sank no fewer than eighty-three US merchantmen as well as the heavier gunboat USS Hatteras (which she lured to her doom by pretending to be a merchant blockade runner), and was probably the most famous ship in the world at the time. The USS Kearsarge had been pursuing the Alabama for a year in European waters when, as she lay at anchor in the Scheldt estuary near Vlissingen on Sunday 12 June 1864, her captain, John A. Winslow, received word from the US minister in Paris that his elusive quarry had steamed into Cherbourg the day before. Winslow wasted no time and two days later found his prey still in Cherbourg roads, where he stopped engines and lay to. Unable to engage within the confines of a neutral port, Winslow retired beyond the three-mile limit required by international law, intending to intercept Alabama when she emerged He took precautions against a surprise night attack but was most worried that Alabama might try to slip away. The following day, however, he received a note from Semmes via the American vice-consul that indicated his intention to fight at the earliest opportunity and begging Winslow not to depart.

The two ships were evenly matched. Both were three-masted and steam-propelled, and if the Kearsarge mounted a combined broadside firing 365 pounds to the Alabama’s total broadside of 264 pounds, the latter’s Blakely guns outranged and were more accurate than the Dahlgrens of the Kearsarge. However, the speed and manœuvrability of the Alabama were declining and Semmes had intended to put her into dry dock for two months and thoroughly clean the keel and overhaul the boilers. Nevertheless, he wrote in his journal that ‘the combat will no doubt be contested and obstinate, but the two ships are so evenly matched that I do not feel at liberty to decline it.’ He had confidence in the ‘precious set of rascals’ that was his crew. Besides, his luck had never yet failed him and he busied the crew preparing the ship, waiting for Sunday, which he deemed his lucky day.

Sunday dawned bright, clear and cool and after a leisurely breakfast the Alabama was cheered out to sea by crowds along the mole and in the upper windows of the buildings, where a fine view could be had of the forthcoming action. Excursion trains had brought sightseers from Paris, and Cherbourg was packed with excited crowds shouting ‘Vivent les Confedérés!’ In a new dress uniform Semmes delivered a stirring oratory to his men before taking station on the horseblock just before the mizzen mast. Then at 1057 hours, with watch in hand, at a range of about a mile, he asked his executive officer if he was ready: ‘Then you may fire at once, sir.’

No hits were scored as the range closed to half a mile, when Winslow returned the fire and the two ships began to circle to starboard, firing furiously at each other. A Blakely round scored a direct hit on the sternpost of the Kearsarge but fortunately for Winslow it was a dud. A three-knot current bore the ships westward and as it did so so their circles became tighter until the range dropped to about a quarter of a mile by the seventh and final revolution. Once they were on target, the US guns inflicted tremendous damage. At the same time, Semmes watched in horror as everything his own guns fired at the Kearsarge bounced harmlessly off the sides, including solid shot. Realizing the desperate state of his old vessel, Semmes ordered full sail for the coast but Kearsarge was not to be denied. When Semmes saw the wreckage to which the lower decks had been reduced, he ordered the colours to be struck saying: ‘It will never do in this nineteenth century for us to go down, and the decks covered with our gallant wounded.’ Captain and crew abandoned the rapidly sinking ship, which went down at 1224 hours, just ninety minutes after she had opened the action.

Only after the battle did Semmes discover that the Kearsarge had 120 fathoms of sheet chain suspended from scuppers to waterline, bolted down and concealed behind an inch of planking: he had been fighting an ironclad! Semmes protested this was unfair. ‘It was the same thing’, he said, ‘as if two men were to go out and fight a duel, and one of them, unknown to the other, were to put on a suit of mail under his outer garment.’ Perhaps, but Commodore David Farragut had employed the same stratagem two years previously, when he ran past the forts into New Orleans.