Douglas Aircraft developed the Model 7B twin-engine light attack bomber in the spring of 1936. The prototype flew for the first time in October 1938. However, due to budget constraints U. S. Army Air Corps officials decided not to purchase the aircraft.

French officials had no such hesitation. In 1939, they ordered 270 of what was now designated the DB-7. Belgium also ordered an unspecified number. When France fell to Germany in 1940, the DB-7s as well as remodeled DB-7As and Bs were shipped instead to Great Britain and redesignated the Boston I, II, and III.

Ironically, Air Corps leaders had already changed their minds by late 1939 following the passage of the bountiful Military Appropriations Act of April 1939. They ordered 63 DB-7s as high-altitude attack bombers with turbosupercharged Wright Cyclone radial engines. The Air Corps redesignated this aircraft the A-20.

After initial flights of the aircraft, the Air Corps decided it did not need a high-altitude light attack bomber but rather a low-altitude medium attack aircraft. To this end, only one A-20 was built and delivered. The final 62 contracted aircraft were built as P-70 night-fighters, A-20A medium attack aircraft, or F-3 reconnaissance aircraft. The lone A-20 was used later as a prototype XP-70 for the development of the P-70 night-fighter version of the Havoc.

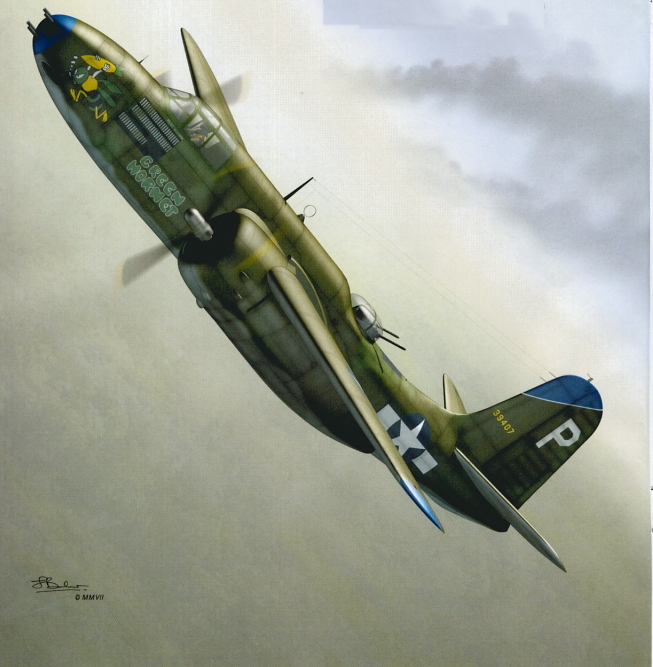

Construction of the A-20A, the first production model, began in early 1940. By April 1941, 143 had been built and delivered to the 3d Bomb Group (Light; 3BG). The aircraft was 47 feet, 7 inches long with a wingspan of 61 feet, 4 inches. It had a gross takeoff weight of 20,711 pounds. Powered by two Wright R-2600-3 or -11 Cyclone radial engines producing 1,600 hp, it had a maximum speed of 347 mph, a cruising speed of 295 mph, and a maximum ferry range of 1,000 miles. It had nine .30-caliber machine guns: four forward-firing in a fuselage blister, two in a flexible dorsal position, one in a ventral position, and two rear-firing guns in the engine nacelles. It had a maximum bombload of 1,600 pounds.

In October 1940, Douglas and Air Corps officials concluded a contract for 999 B models. Although it used the same Wright 2600-11 engines as the last 20 -A models, it was lighter and armed like the DB-7A. The A-20B had two .50- caliber machine guns in the nose and only one .50-caliber gun in the dorsal mount. Its fuselage was 5 inches longer; it had a 2,400-pound maximum bombload, a maximum speed of 350 mph, a cruising speed of 278 mph, and a 2,300-mile ferry range. Eight were sent to the Navy as DB-2 targettowing aircraft, and 665 were delivered to the Soviet Union as Lend-Lease aircraft.

Douglas built 948 C models, 808 at the Douglas plant in Santa Monica, California, and 140 under contract at the Boeing plant in Seattle, Washington. The C was patterned after the A model. Its Wright R-2600-23 Cyclone radial engines provided this heavier aircraft a maximum speed of 342 mph. Like all Havoc models, it had four crew members-a pilot, navigator, bombardier, and gunner. Originally built to be Royal Air Force and Soviet Lend-Lease aircraft, the Cs were diverted to the U. S. Army Air Forces once the United States entered World War II.

More G models were produced than any other A-20 version. Douglas built 2,850 in 45 block runs. The major differences were new and varying armaments, most notably the addition of four forward firing 20mm cannons in the nose. After block run number five, these were again replaced with six .50-caliber machine guns.

Douglas built 412 H models, 450 J models, and 413 K models. They were heavier at 2,700 pounds and had Wright R-2600-29 Cyclone supercharged radial engines producing 1,700 hp and flying at 339 mph. They carried 2,000 pounds of bombs internally and 2,000 externally.

A-20 production ended in September 1944. Douglas and other plants built 7,230 A-20s. They served in every theater of war and with the USAAF, the RAF, as well as the Australian, Soviet, and several other Allied air forces. More A-20s were built than any other attack-designated aircraft to serve in World War II.

The first customer for the Model 7B was the French Armee de l’Air. They had ordered 370 aircraft by the time of the German invasion in May 1940, and shortly thereafter ordered 480 more DB-7Cs, re-designated as DB-73s at French insistence. The British authorities had ordered another 300 and the USAAC had ordered the type as the A-20.

Confusingly, the French aircraft were designated as DB-7s (with l, 200hp Pratt and Whitney Twin Wasp S3C4-G engines) or DB-7As (with Wright Double Cyclones). The DB-7B aircraft ordered by the RAF were similar to the USAAC’s A-20As, structurally improved, fitted with an enlarged tailfin, and powered by l, 600hp Double Cyclones but with British armament.

With the collapse of France, the RAF received about 200 of the French DB-7s (some which had not been delivered, others flown by defecting crews) and all 100 of the undelivered DB-7As. These respectively became Havoc I night fighters and Boston I trainers, while the DB-7As became Havoc IIs. Some Havocs retained glazed noses and were used as intruders, while others had AI radar and solid noses mounting eight 0.303-in machine guns. Some were even fitted with nose-mounted searchlights as `Turbinlite Havocs’, operating in con¬ junction with Hurricane night fighters. The first Havocs entered service in October 1940.

The Royal Air Force’s intended DB-7Bs (and the French DB-73s, which were delivered to the same standards) were known as Douglas Boston Ills, and were used as day bombers by Bomber Command’s No. 2 Group. These replaced Blenheims from August 1941. The Bostons proved fast and was 80mph (128km/h) quicker than a Blenheim. The aircraft was rugged, and was used for a number of highly successful high profile attacks on targets in Occupied Europe. These included the Philips Radio factory at Eindhoven in southern Holland, the Matford works at Poissy, near Paris, and numerous enemy airfields. They were also used in North Africa, the Mediterranean and Italy.

First squadron to equip with Boston B.IIIs, was 88 ‘Hong Kong’ Squadron of 2 Group, Bomber Command. Before doing so it received a number of Boston Is (beginning with AW398 on December 1, 1940) and ‘IIIs (beginning with AE467 on March 30 1941), while based at Sydenham, Belfast. In August, when it operated Blenheim IVs from Attlebridge (Norfolk), the squadron received some non-operational Boston Ills, its first operational Mk. IIIs arriving in October, when operations on Blenheims ceased. In November-December 1941, 226 Squadron at Wattisham was rearmed with Boston Ills, and in February 1942, 107 Squadron at Great Massingham was similarly rearmed; like 88 Squadron both these units had previously flown Blenheim IVs. When 342 ‘Lorraine’ Squadron, Free French Air Force, formed at West Raynham in April 1943 from what had previously been known merely as the Lorraine Squadron, F. F. A. F., it too was armed with Bostons-Mk. IIIAs, the Lease-Lend version of the Mk. III, from which latter it could be distinguished by the stub exhausts in place of the single long exhausts with flame-traps. In August and September 1943, 88, 107, and 342 Squadrons moved to Hartford Bridge (later renamed Blackbushe) as 137 Wing, Second Tactical Air Force, 226 Squadron having rearmed with Mitchells. The Boston IIIs had gradually been replaced in 88 and 107 Squadrons by Mk. IIIAs during the first half of the year, some of the Mk. IIIs being sent to the Middle East. By mid-1944 some Boston IVs (A-20Js) were in the squadrons, these Lease-Lend machines having a one-piece Perspex nose and a Martin two-gun dorsal turret. In October 1944, 137 Wing comprising now 88 and 342 Boston Squadrons and 226 on Mitchells, moved to Vitry-en-Artois, France. 88 Squadron disbanded there in April 1945 and at the same time the other two squadrons moved to Gilze-Riyen (Airfield B. 77), Holland.

First occasion when Boston IIIs were used operationally was February 12 1942, when ten machines of 88 and 226 Squadrons took part in the armed search for the German warships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, which had escaped from Brest and proceeded up the Channel. Only one machine-from 226 Squadron managed to find a target and deliver an attack. Bostons made their first attack on a land objective on March 8 1942, when aircraft of 88 and 226 Squadrons made a low-level raid on Matford Works at Poissy, while others from the same units took part in a diversionary Circus operation against a power-station at Comines. The Boston which led the Matford mission -Z2209 ‘G-George’, captained by 226’s CO., W/Cdr V. S. Butler-was lost on the return journey. It was damaged either by light flak or bomb blast, and when a few miles from the target it was seen to be in difficulties; it struck a tree with its port wing, stood on its tail in a vain attempt to clear more trees, and then crashed. The rest of the force returned safely. Daylight Circus operations formed a large part of the Boston’s early activities over Europe, their purpose being to bring the Luftwaffe to battle. They were flown either at low or medium level and the targets, in addition to power-stations, included airfields, marshalling-yards, and ports. The Bostons also flew unescorted missions, diving out of cloud to attack their objectives and returning to such cover for the homeward flight. On August 17, 1942, during the commando raid on Dieppe, they did valuable work in laying smokescreens to cover both the assault and withdrawal. Another special operation came in December when they led the famous raid on the Philips radio and valve factory at Eindhoven in Holland. Towards the end of 1943, 137 Wing’s Bostons joined the assault against the German V-1 depots and sites in northern France, and when D-Day finally came they repeated what they had done at Dieppe and laid smoke-screens over the beaches. After this the Bostons operated in close support of the advancing Allied Armies. on the Continent, eventually winding up their offensive with a series of attacks launched from their base in Holland on targets in western Germany.

Boston IIIs crossing the sea at low level en route for enemy territory in late 1942. The machine in the foreground sports the code letters ‘RH’ denoting 88 Squadron.

(Note: Boston Ills were also used by the U. K.-based 23, 418 (R. C. A. F.) and 605 Squadrons during the period 1942-3, and although these units did do some bombing, they were essentially fighter-intruder units.)

In the spring of 1943, 326 Wing, Tactical Bomber Force, in North Africa, comprising 18 ‘Burma’ and 114 ‘Hong Kong’ Squadrons, relinquished the Bisleys which it had been operating and converted to Boston Ills (later supplemented by Mk. IIIAs) which it first took into action in close-support of the ground-forces during the closing stages of the Tunisian campaign. Like their U. K.-based counterparts, the squadrons adopted the ‘box-of-six’ bombing technique and usually operated with a fighter escort.

The North African campaign over, the squadrons turned their attention to the enemy-held islands of Pantellaria, Lampedusa, and Sicily, stepping-stones to Italy, and then bombed targets in Italy itself, moving across via Sicily to the Italian mainland in the wake of the advancing Allied Armies. Day and night missions were flown during this period-the Bostons sometimes acting as pathfinders-and by late 1944 there were four R. A. F. Boston squadrons operating in Italy, the newcomers being 13 and 55 Squadrons, both of which converted to Boston IVs from Baltimores. The four Boston squadrons formed 232 Wing of Mediterranean Allied Tactical Air Force, their crews, because of their night-flying role, becoming known as ‘Pippos’, a contraction of pipistrello (bat), and a word which, in the singular, was the name of a comic character, cf. ‘batty’. 13 Squadron claims to have introduced the ‘Balbo’ bombing technique in which one aircraft marked the target with flares and incendiaries for others to bomb at half-second intervals.

Night armed reconnaissance was the major role of the Bostons during the Italian campaign, and in December 1944, when 18 and 114 Squadrons operated in this role over the Fifth Army front, they drew praise from General Mark Clark, the Fifth Army’s C.-in-C. He said that their work was invaluable to his Army, which would otherwise have remained ignorant of the enemy’s movements during the hours of darkness. Tactical Air Force went so far as to say that the work of six Bostons during the night was more valuable than an entire wing of day-bombers.

During April 1945, all four Boston squadrons they were now flying Mk. IVs and Vs-made night attacks in support of the Eighth Army’s final assault which was to defeat the German forces in Italy. The Mk. V was the R. A. F. version of the A-20K and was generally similar to the Mk. IV but had a revised cockpit for more accessible bombing controls. Most of this bombing was done on timed runs from the Army’s landmark beacons, the principal targets being gun-positions, strong points, M. T. and pontoon and ferry crossings over rivers. Final operational task of the Bostons was the dropping of surrender leaflets to a force of Germans still holding out north of Gemona, on May 4 and 5.

After the cessation of hostilities all Lease-Lend Bostons were returned to the U. S. Government, which then reduced them to scrap, as it also did with most other returned Lease-Lend types.

The RAF also took delivery of Boston IVs (A-20Gs) and Boston Vs (A-20Js), taking the total number of Bostons and Havocs to more than 1,000. Some of these served in Europe until April 1945, and elsewhere the type remained in service a little longer. Russia received about 3,600 DB-7s, while the USAAF used 1,962 aircraft. These served in Europe and the Pacific, winning a reputation for toughness and dependability.