Hypersonic Glide Body

Today, with modern air power operating inside the atmosphere, we can impose kinetic effects at the speed of sound. With the maturing of hypersonic weapons, we will be able to do that at multiples of the speed of sound.

The March 19 test of a hypersonic glide body at the Pacific Missile Range Facility in Hawaii is just the start for the Defense Department, the assistant director for hypersonics in the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Research and Engineering said, and after ample flight testing, the department will move toward developing weapons from the concepts it’s been testing.

“Over the next 12 months really what we will see is continued acceleration of the development of offensive hypersonic systems,” Michael E. White said today during an online panel discussion hosted by Defense One.

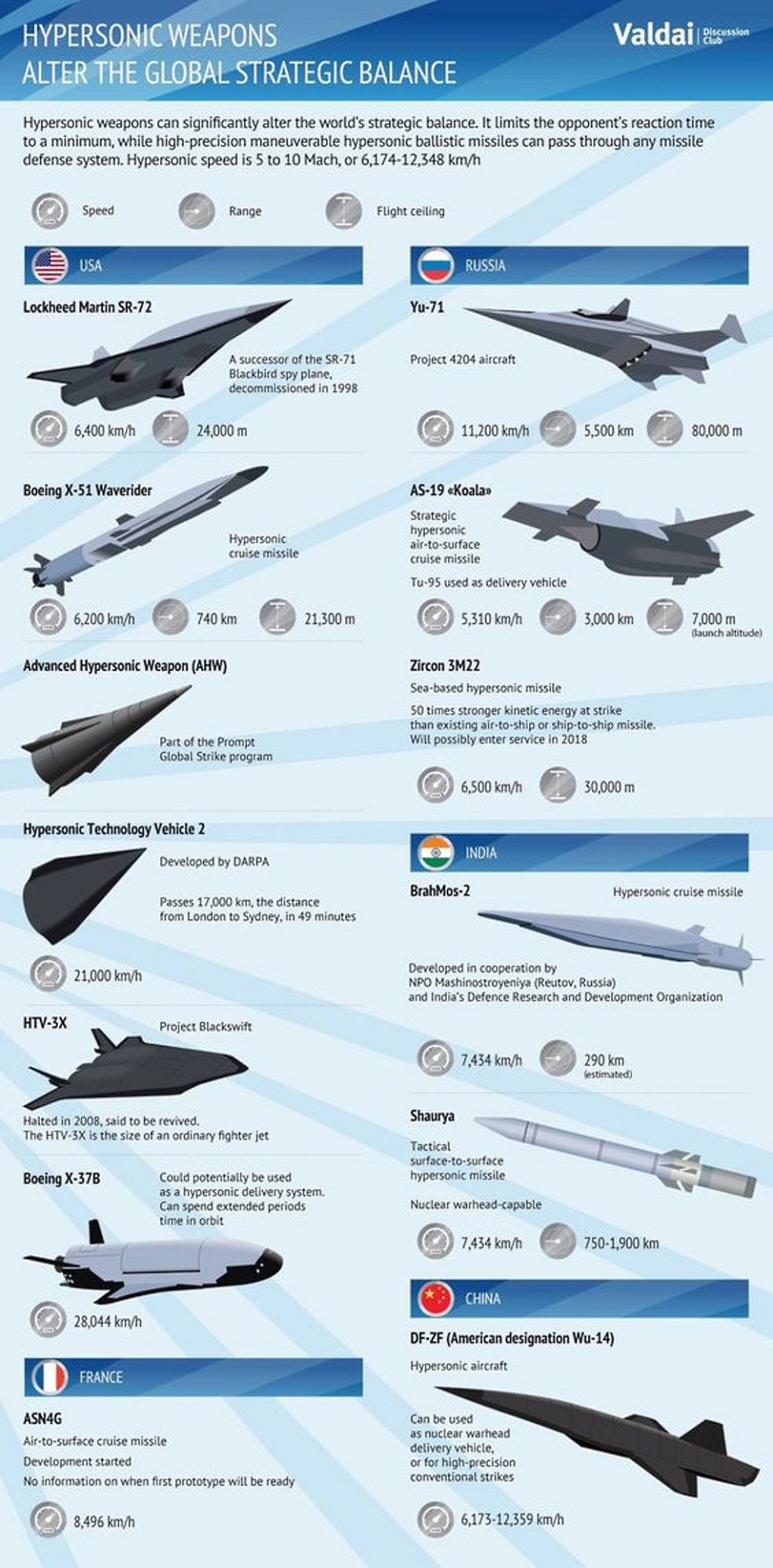

Hypersonic weapons move faster than anything currently being used, giving adversaries far less time to react, and they provide a much harder target to counteract with interceptors. White said DOD is developing hypersonic weapons that can travel anywhere between Mach 5 and Mach 20.

The March test of the hypersonic glide body successfully demonstrated a capability to perform intermediate-range hypersonic boost, glide and strike, he said. That test, White added, begins a “very active flight test season” over the next year, and beyond, to take concepts now under development within the department and prove them with additional tests.

“A number of our programs across the portfolio will realize flight test demonstration over the next 12 months and then start the transition from weapon system concept development to actual weapon system development moving forward,” he said.

Also part of the department’s efforts is the defense against adversary use of hypersonic missile threats — and that may involve space, said Navy Vice Adm. Jon Hill, director of the Missile Defense Agency. Land-, silo- or air-launched hypersonic weapons all challenge the existing U.S. sensor architecture, Hill said, and so new sensors must come online.

“We have to work on sensor architecture,” Hill said. “Because they do maneuver and they are global, you have to be able to track them worldwide and globally. It does drive you towards a space architecture, which is where we’re going.”

DOD is now working with the Space Development Agency on the Hypersonic and Ballistic Tracking Space Sensor to address tracking of hypersonics, the admiral said. That system is part of the larger national defense space architecture.

“As ballistic missiles increase in their complexity … you’re going to be able to look down from cold space onto that warm earth and be able to see those,” he said. “As hypersonics come up and look ballistic initially, then turn into something else, you have to be able to track that and maintain track. In order for us to transition from indications and warning into a fire control solution, we have to have a firm track and you really can’t handle the global maneuver problem without space.”

Hill said the department already has had a prototype of such satellites in space for some time, and is collecting data from it. In the early 2020s, he added, additional satellites will also go up to demonstrate tracking ability.

Technology

Flight at five times the speed of sound and above promises to revolutionize military affairs in the same fashion that the combination of stealth and precision did a generation ago. Hypersonic air weapons offer advantage in four broad areas. They counter the tyranny of distance and increasingly sophisticated defences; they compress the shooter-to-target window, and open new engagement opportunities; they rise to the challenge of addressing numerous types of targets; and they enhance future joint and combined operations. Within each of these themes are other advantages which, taken together, redefine air power projection in the face of an increasingly unstable and dangerous world.

The Physical Component is the one with which airmen and women tend to be instinctively the most comfortable. It is about the platforms, capabilities, weapons and `stuff’ that, to many, define what the RAF `is’. This applies just as much to the Space domain as it does to the Air domain, and the best way of achieving this may be to address both domains as seamless entities. In years gone by, the reality of doing just that was limited by technology separation: what worked in space did not work in the air and vice-versa. But modern technology – especially with hypersonic engines, pseudo-satellites, high-resolution optics and radar technologies – makes it conceivable that, with appropriate investment choices, future military capabilities could have the potential to be employed in both domains, perhaps even within the same mission. These technological enhancements are also likely to deliver the improvements in speed, reach, persistence, coverage, survivability, and precision necessary to provide an increased range of options for military commanders and political masters alike. But to embrace this new technology will undoubtedly require us to change our preconceived ideas of air power as being delivered predominantly from manned, fixed-wing, air-breathing platforms which operate at relatively low altitude. The blurring of the Air and Space domains allows us to translate our experiences of inner atmosphere aviation into even higher vertical limits and far greater ranges of effect. In the remaining paragraphs of this section, I will explore what I believe to be the four greatest technological developments that will allow us to transform air and space power over the next 30 years.

Hypersonic Engines.

At a glance, hypersonic engines may appear to be a `silver bullet’ which will unleash air and space power in the twenty-first century. This field of technology shows great promise, and much is possible within the next couple of decades providing there is investment in the emergent technology. So, what can hypersonics offer the Air environment? A good place to start would be to look at what Reaction Engines Limited (REL) has to offer with their experimental Synergetic Air-Breathing Rocket Engine, or SABRE. 9 Initial work looks incredibly exciting and could give rise to a working platform by 2030 that is capable of Mach 5+ and offers high cadence space access as well as long range inner-atmosphere flight. Such technology also appears promising because it purportedly offers `speed as the new stealth’ and potentially increases the survivability against an array of current and anticipated anti-access systems. Furthermore, while the technology claims to enable space access it can also, in theory at least, provide a vehicle from which a space payload could be launched. But hypersonic technology is not limited to just platforms. It can be applied effectively to weapons: air and groundlaunched, offensive and defensive. Whatever the manner of its employment, hypersonic technology has the potential to provide significant benefit to all operating domains – a true force multiplier. Thus, even at this relatively early stage in its programme, hypersonic technology represents a very strong candidate to address the physical aspects of the blurred Air and Space domains. While there are numerous hypersonic technologies under development, SABRE is novel, it is British, and therefore offers a sovereign capability with all the accordant benefits for our national prosperity agenda.

Hypersonic Vehicles Aerial vehicles that can travel in excess of five times the speed of sound, or Mach-5, are labelled hypersonic. Hypersonic weapons can be broadly divided into two categories, that is, Hypersonic Glide Vehicles (HGV) and Hypersonic Cruise Missiles (HCM).

Hypersonic Glide Vehicles

The aerodynamic HGV is a boost-glide weapon-it is first `boosted’ up into near space atop a conventional rocket and then ejected at an appropriate altitude and speed. The height at which it is released depends on the intended trajectory to the target. Thereafter, the HGV starts to fall back to Earth, gaining more speed and gliding along the upper atmosphere, before diving on the target.

Hypersonic Cruise Missiles

An HCM on the other hand, is typically propelled to high speeds (around Mach 4 to 5) initially using a small rocket; thereafter, an air-breathing supersonic combustion ram jet or a `scramjet’ accelerates it further and maintains its hypersonic speed. HCMs are hypersonic versions of existing cruise missiles but would cruise at altitudes of 20-30 km in order to ensure adequate pressure for its scramjet. Standard cruise missiles are difficult to intercept-and the speed of the HCM and the altitude at which it travels complicates this task of interception manifold. The United States’ underdevelopment `WaveRider’ is a typical HCM. Russia’s HCM, the aircraft-launched Kh-47M2 `Kinzhal’, (Dagger), has a reported top speed of Mach-10 and a range of about 2000 km. India’s underdevelopment `Hyper Sonic Technology Demonstrator Vehicle’ (HSTDV) too, capable of speeds around Mach-7, falls in the category of an HCM.

1. Aerial vehicles that can travel in excess of Mach-5 are labelled as hypersonic.

2. Three nations (Russia, China, USA) have been testing hypersonic glide vehicles (HGVs), although a number of other countries are also pursuing hypersonic programmes.

3. An HGV, armed with a nuclear or a conventional warhead, or merely relying on its kinetic energy, has the potential to allow a military to rapidly and pre-emptively strike distant targets anywhere on the globe within hours or less.

4. On account of their quick-launch capability, high speed, lower altitude and higher manoeuvrability vis-a-vis Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles , HGVs are difficult to detect and intercept with existing air and missile defence systems.

5. This capability could tempt a nation to consider using HGVs for a disarming and first-strike on an adversary’s nuclear arsenal.

6. While numerous challenges remain, operational deployment of HGVs would thus compel target nations to set their nuclear forces on a hair-trigger readiness and “launch on warning” alerts, leading also to the devolution of command over nuclear weapons.

7. Overall, this would aggravate strategic instability, and also generate unacceptable levels of instability in crisis management at many levels.