The Tsybin RSR (Reactivnyi Strategicheskii Razvedchik, Russian for “jet strategic reconnaissance”) was a Soviet design for an advanced, long-range, Mach 3 strategic reconnaissance aircraft.

The preliminary project for the revised aircraft, able to take off in the conventional manner, was dated 26th June 1957. Design proceeded rapidly, and in parallel OKB-256 created a simplified version, using well-tried engines, which could be got into the air quickly to provide data. These data became available from April 1959, and resulted insignificant changes to the RSR. The basic design, however, can be described here.

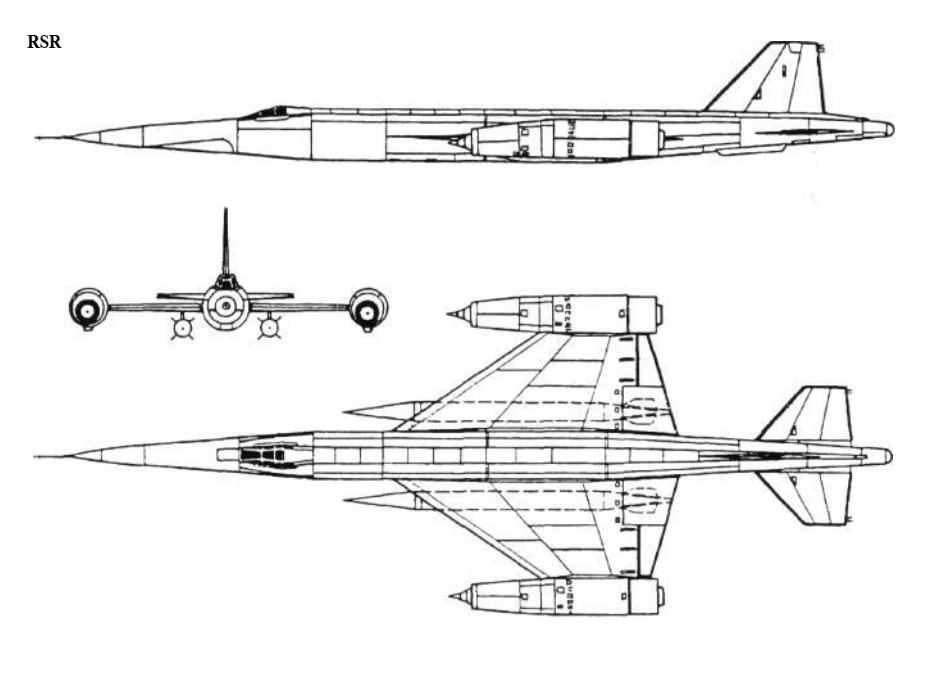

Though the RSR was derived directly from the 2RS, it differed in having augmented bypass turbojet engines (low-ratio turbofans) and strengthened landing gear for conventional full-load take-offs. A basic design choice was to make the structure as light as possible by selecting a design load factor of only 2.5 and avoiding thermal distortion despite local skin temperatures of up to 220°C. By this means the use of steel and titanium was almost eliminated, though some skins (ailerons, outer wing and tail torsion boxes) were to be in aluminum/beryllium alloy. As before, the wing had a t/c ratio of 2.5 per cent, 58° leading-edge sweep and three main and two secondary spars. The tips, 86mm deep, carried Solov’yov D-21 bypass engines. These bore no direct relationship to today’s D-21A1 by the same design team. They were two-shaft engines with a bypass ratio of 0.6, and in cruising flight they were almost ramjets. Sea-level dry and augmented ratings were 2,200kg (4,850 Ib) and 4,750kg (10,472 Ib) respectively. Dry engine mass was 900kg (1,984l b) and nacelle diameter was 1.23m (4ft 1/2in). The fuselage had a fineness ratio of no less than 18.6, diameter being only 1.5m (4ft 1in). All tail surfaces had a t/c ratio of 3.5 per cent, and comprised a one-piece vertical fin with actuation limits of ±18° and one-piece tailplanes with limits of + 10°/-25°. All flight controls were fully powered, with rigid rod linkages from the cockpit and an artificial-feel system. The main and steerable nose landing gears now had twin wheels, and were supplemented by single-wheel gears under the engines, all four units hydraulically retracting to the rear. A braking parachute was housed in the tailcone. A total of 7,600kg (16,755 Ib) of kerosene fuel was housed in integral tanks behind the cockpit and behind the wing, plus 4,400kg (9,700 Ib) in two slender (650mm, 2ft 3/5in diameter) drop tanks. An automatic trim control system pumped fuel to maintain the centre of gravity at 25 per cent on take-off, 45.0 in cruising flight and 26.4 on landing. In cruising flight the cockpit was kept at 460mm Hg, and the pilot’s pressure suit maintained 156mm after ejection. An APU and propane burner heated the instrument and camera pallets which filled the centre fuselage, a typical load comprising two AFA-200 cameras (200mm focal length) plus an AFA-1000 or AFA-1800 (drawings show four cameras), while other equipment included optical sights, panoramic radar, an autopilot, astro-inertial navigation plus a vertical gyro, a radar-warning receiver and both active and passive ECM (electronic countermeasures)

During construction this aircraft was modified into the RSR R-020.

Tsybin RSR, R-020

A simplified, full-sized aerodynamic prototype for the novel layout, the NM-1 was built in 1957. Intended for low-speed handling tests, the NM-1 had a steel-tube fuselage with duraluminium and plywood skinning. This aircraft, powered by two Mikulin AM-5 turbojets first flew on 7 April 1959.

Upon receipt of data from the NM-1, the RSR had to be largely redesigned. Construction was only marginally held up, and in early 1959 drawings for the first five pre-series R-020 aircraft were issued to Factory No 99 at Ulan-Ude. However, Tsybin’s impressive aircraft had their commercial rivals and political enemies, some of whom just thought them too ‘far out’, and in any case vast sums were being transferred to missiles and space. On 1st October 1959 President Khrushchyev closed OKB-256, and the Ministry transferred the RSR programme to OKB-23 (General Constructor VM Myasishchev) at the vast Khrunichev works. The Poberez’ye facilities were taken over by A Ya Bereznyak. The Khrunichev management carried out a feasibility study for construction of the R-020, but in October 1960 Myasishchev was appointed Director of CAHI (TsAGI). OKB-23 was closed, and the entire Khrunichev facility was assigned to giant space launchers. The RSR programme was thereupon again moved, this time to OKB-52. At first this organization’s General Constructor V N Chelomey supported Tsybin’s work, but increasingly it interfered with OKB-52’s main programmes. In April 1961, despite the difficulties, the five R-020 pre-series aircraft were essentially complete, waiting only for engines. In that month came an order to terminate the programme and scrap the five aircraft. The workforce bravely refused, pointing out how much had been accomplished and how near the aircraft were to being flown. The management quietly put them into storage (according to V Pazhitnyi, the Tsybin team were told this was ‘for eventual further use’). Four years later, when the team had dispersed, the aircraft were removed to a scrapyard, though some parts were taken to the exhibition hall at the Moscow Aviation Institute.

The airframe of the 1960 RSR differed in several ways from the 1957 version. To avoid surface-to-air missiles it was restressed to enable the aircraft to make a barrel roll to 42km (137,800ft). The wings were redesigned with eight instead of five major forged and machined ribs between the root and the engine. The leading edge was fitted with flaps, with maximum droop of 10°. The trailing edge was tapered more sharply, and area was maintained by adding a short section (virtually a strake) outboard of the engine. These extensions had a sharp-edged trapezoidal profile. According to Tsybin These extensions, added on the recommendation of CAHI, did not produce the desired effect and were omitted’, but they are shown in drawings. In fact, CAHI really wanted a total rethink of the wing, as related in the final Tsybin entry. The tailplane was redesigned with only 65 per cent as much area, with sharp taper and a span of only 3.8m (12ft 5 1/2in). Its power unit was relocated ahead of the pivot, requiring No 6 (trim) tank to be moved forward and shortened. The fin was likewise greatly reduced in height and given sharper taper, and pivoted two frames further aft. The ventral strake underfin was replaced by an external ventral trimming fuel pipe. The main landing gear was redesigned as a four-wheel bogie with 750 x 250mm tyres, and the outrigger gears were replaced by hydraulically extended skids in case a nacelle should touch the ground. The pilot was given a better view, with a deeper canopy and a sharp V (instead of flat) windscreen. The camera bay was redesigned with a flat bottom with sliding doors. The nose was given an angle-of-attack sensor, and a pitot probe was added ahead of the fin. The drop tanks were increased in diameter to 700mm (2ft 31/2in) but reduced in length to 5.8m (19ft) instead of 11.4m (37ft 4Min). Not least, the D-21 engines never became available, and had to be replaced by plain afterburning turbojets. The choice fell on the mass-produced Tumanskii R-l IF, each rated at 3,940kg (8,686 Ib) dry and 5,750kg (12,676 Ib) with afterburner. These were installed in longer and slimmer nacelles, with inlet sliding centre bodies pointing straight ahead instead of angled downwards.

There is no reason to doubt that the pre-series RSR, designated R-020, would have performed as advertised. It suffered from a Kremlin captivated by ICBMs and space, which took so much money that important aircraft programmes were abandoned. The United Kingdom similarly abandoned the Avro 730, a reconnaissance bomber using identical technology, but in this case it was for the insane reason that missiles would somehow actually replace aircraft. Only the USA had the vision and resources to create an aircraft in this class, and by setting their sights even higher the Lockheed SR-71 proved valuable for 45 years.

Specifications (R-020)

General characteristics

Crew: 1

Length: 28 m (91 ft 10 in)

Wingspan: 10.66 m (35 ft 0 in)

Wing area: 64 m2 (690 sq ft) [8]

Empty weight: 9,100 kg (20,062 lb)

Gross weight: 19,870 kg (43,806 lb)

Fuel capacity: 10,700 kg (23,589 lb)

Powerplant: 2 × Tumansky R-11F turbojet engines, 38.64 kN (8,686 lbf) thrust each dry, 60.65 kN (13,635 lbf) with afterburner

Performance

Maximum speed: 2,600 km/h (1,600 mph, 1,400 kn) at 12,000 m (39,370 ft)

Maximum speed: Mach 2.44

Range: 4,000 km (2,500 mi, 2,200 nmi)

Service ceiling: 22,500 m (73,800 ft) [8]

Take-off run: 1,200 m (3,937 ft)

Landing run: 800 m (2,625 ft) with brake parachute