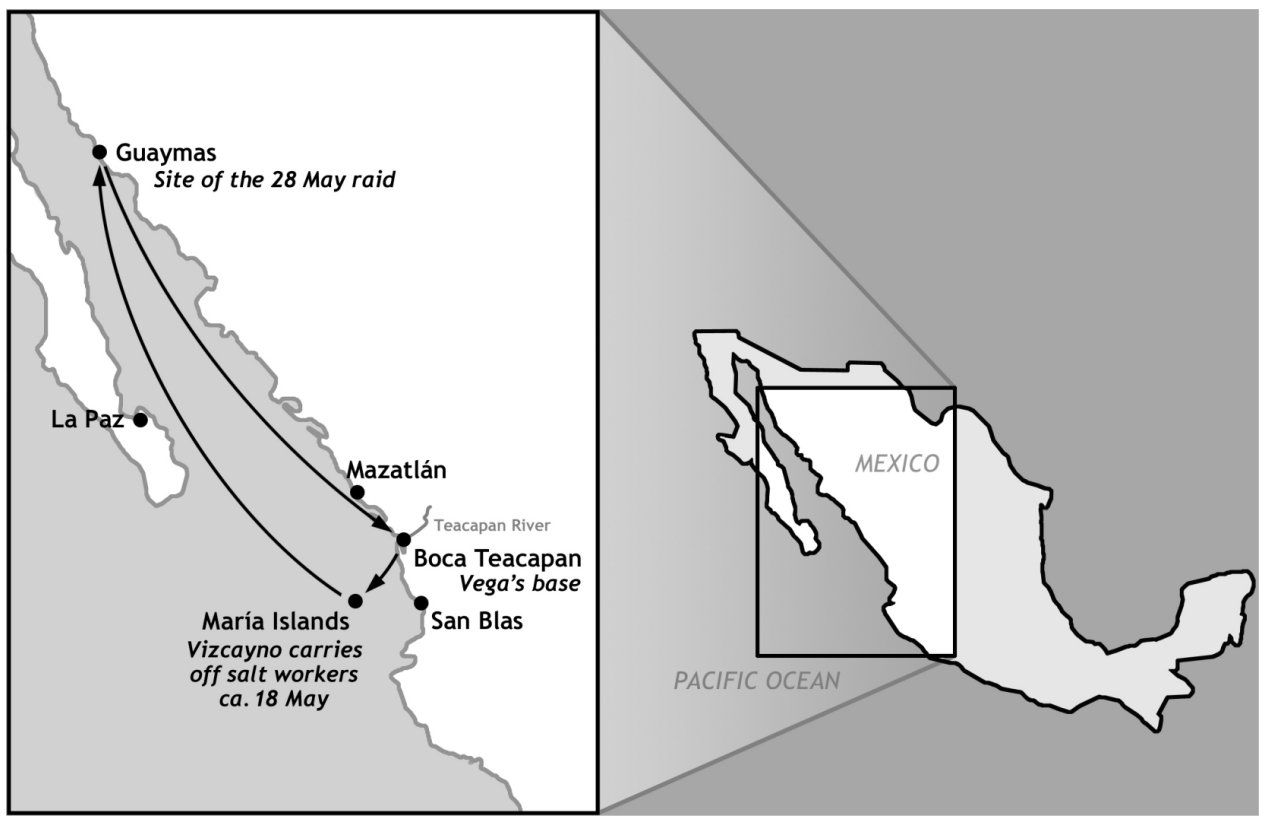

The Path of the Forward under the command of Fortino Vizcayno, starting at Boca Teacapan (May 1870).

The USS Mohican’s Pursuit of the Forward, starting at Guaymas (June 1870).

The human cost of the raid was relatively minor. According to the Mexican military commander that chased the Forward from Guaymas, one Mexican soldier had suffered injuries because of the raid and “we have to lament one death on our part in the said engagement.” Another anonymous source reported “several deaths” without elaborating. Moreover, the pirates kidnapped a number of people during the raid, though two prisoners escaped as the Forward prepared to disembark and the pirate crew released the remainder but for Alfonso Mejia, Guaymas customs collector and son of Juarez’s secretary of war and marine. This abduction occurred despite the “urgent solicitation” of Willard, who received assurances from Vizcayno that “no fears need to be entertained for [Mejia’s] life.”

he property losses at Guaymas were more extensive. A comprehensive list of losses compiled on 13 June 1870 by the American consul at Mazatlan found that “English, American, and Germans are the victims” of the robbery. Ortiz Hermanos calculated a total of $42,308 in goods stolen from their warehouse, $12,985 belonging to the English firm Rogers, Meyer, and Company based in San Francisco, $435 belonging to the English firm J. Kelly and Company of Mazatlan, $27,930 belonging to the German houses of Melchors Successor of Mazatlan and T. Heymann of Mazatlan, and finally, $958 in goods from three Mexican firms.

The Forward left Guaymas with Mejia aboard and headed south, never completing the optional mission of raiding La Paz in Baja California. In fact, Willard reported the rumor that the Forward was going south to San Blas to join with Vega’s forces to take Mazatlan, and somewhat prophetically noted that, “General Vega and his Western Republic are still in the balance and probably the next three months will decide its fate.”

Despite the threat that the U. S. consul believed the Forward posed to the Mexican republic, the Juarez regime’s lack of capable naval forces seriously hindered its efforts to punish Vega. The Mexican general-in-chief in charge of the region, Bibiano Davalos, thus articulated a solution in a letter to Consul Sisson at Mazatlan. “[I]t is the absolute duty of the naval forces to protect [the population],” wrote Davalos, “but unfortunately, my government does not possess any.” In view of the fact that “the United States man-of-war Mohican is at the present in these waters,” he asked Sisson to “exert [his] influence with the commander of that ship, so that he may contribute to the apprehension of those criminals, who are doubtless near this coast, as they have two sailing vessels in tow.” Later that month the government newspaper the Diario Oficial used this communication to claim that Sisson “ordered the steam man-of-war Mohigan [sic] to set sail in pursuit of the pirates,” on the advice of Davalos. Of course, such an order could not and did not come from Sisson. No order, in fact, ever came to the Mohican from any American official.

The same day that Davalos sent this request to Sisson in Mazatlan, Commander William Low’s USS Mohican entered Guaymas for supplies and there Low first heard with disgust the results of the Vega raid on the city. He reported his intentions – emphatically – to the Navy Department. Arguing that the Forward “was acting as a vessel of war, without the proper commission [from San Salvador] to act,” and that “she was fitted out on the pretence of being engaged in acts of civil war, but in reality for the purpose of robbery,” Low “deemed it [his] imperative duty to regard her as a piratical craft, and, in the assurance of the security of navigation, equally [his] duty to pursue, and, if possible, to capture or destroy her.” Months later, Commodore William Taylor, commanding the North Squadron of the Pacific Fleet, added that Low also suspected the pirates would continue south to attack “one of the Panama steamers, and perhaps the Continental, which runs between Guaymas, Mazatlan, and San Francisco,” though neither Low nor any other American naval officer offered corroborating written evidence for this suspicion.

Low immediately left Guaymas and steamed after the Forward, but rather circuitously as it turned out. The Mohican first touched at Altata to the south two days later on faulty intelligence that the pirate ship went there. The American warship then departed for La Paz, Baja California. Not finding the Forward at that port, Low took on coal and, on 11 June, left for Ceralbo Island in the Gulf of California. Low next anchored at Mazatlan on 14 June, where he met with Consul Sisson and Mexican authorities, receiving their requests to act. Using language that indicated a higher purpose than simply aiding Mexican authorities, Low stated that while at this city he “received additional information confirmatory of my opinion that the Forward was a piratical craft under the law of nations, and that I should be derelict in my duty not to make every effort to take her.”

Why did Low so determinedly characterize the Forward as a pirate ship? While the definition of piracy then as now is fluid – one man’s pirate is another man’s high-seas freedom fighter, after all – doubtlessly Low’s recent experience during the Civil War (1861-1865) influenced his reaction to the Forward’s raid on Guaymas. Low was well aware of one of the Navy’s principal duties during that conflict: the pursuit and destruction of Confederate commerce raiders such as the CSS Alabama. In fact, Low had personal experience with this mission; between 1862 and 1863, he commanded the USS Constellation of the Mediterranean Squadron and pursued these raiders. Thus, in 1870 Low would have found parallels between the Alabama and the Forward, both being ships of an unrecognized rebellion engaging in raiding, though the Forward perpetrated her piracy on land rather than on water. Not surprisingly, Low’s 1870 response to the Forward echoed that of Captain John Winslow of the USS Kearsarge in the pursuit of the CSS Alabama in 1864: to capture or to destroy the raider.

Low was not the only one to view the Forward as a pirate. For example, fifty years after the incidents described here Brownson recalled that upon hearing about the depredations of the Forward at Guaymas he felt that “this was nothing more or less than piracy according to all authorities and international law, and [the Forward] was liable to seizure by any nation in any waters.” Barrow, 139; Low to Robeson, 19 June 1870, enclosed in “Report of the Secretary of the Navy,” in House Exec. Doc. 1, 41 Cong., 3 sess., serial 1448, 145.

Even so, Low still used local Juarista officials to justify his pursuit of the Forward to his superiors. A later report from Commodore Taylor stated that “Commander Low decided upon his course of action after free conference with Governor Rubi, of the state of Sinaloa, General Darlus [sic], commanding the forces in that state, and himself; and that the attack was made at the request of those authorities.” In an even later report, Taylor added “Señor Supulvida, collector of customs at Mazatlan” to this group.

Even with the diplomatic cover these local officials gave Low, his decisiveness remained atypical for a ship commander on the Pacific Station in the 1870s. Often, Pacific Station commanders would only “proceed with caution, trying to decide the case on its merits . . . [knowing] his conduct might become the subject of official inquiry,” according to historian Robert Erwin Johnson. In Low’s case, requests by Mexican and American diplomatic officials gave him confidence to track down and to destroy the pirate ship with little fear of protests from Mexico and censure by his superiors.

Low took the Mohican in pursuit of the Forward from Mazatlan, this time with correct intelligence that the pirate ship had anchored somewhere to the south of the city. After sailing for about 140 miles, the Mohican put in at San Blas and received word that the Forward sat at the mouth of the Teacapan River, about 75 miles back north. Low steamed north, arriving on 16 June. Finding the mouth not navigable with his deep-draft ship, Low then devised a plan for a brown-water expedition under his second-in-command, Lieutenant Brownson.

Low ordered Brownson to take upstream “all the boats of the ship, with the exception of the dinghy” and engage the Forward. Ideally, Brownson should “endeavor to take possession of her and bring her down to the bar in readiness when the tide serves,” permitting him to “use the howitzer when within good range of the steamer to intimidate the crew” and take the ship. Low also provided a contingency plan if the pirates defended the Forward too effectively – he ordered Brownson simply to return to the Mohican. Finally, Low concluded with some practical advice, to “spare the men all unnecessary exposure to the sun” after the Forward’s capture.

Thus, starting at 2 am on 17 June 1870, Brownson led an expedition of “six boats and about 60 men in all” in search of the Forward at some point inland. Even before entering the river, the expedition encountered danger. Brownson needed the expertise of a man “who had recently enlisted at Mazatlan” to find a channel through “the heaviest surf [he] had ever been through,” as he wrote some years later. Overcoming the surf, the six craft entered the river, and using intelligence gleaned from trustworthy children at the small native village of Teacapan, Brownson believed the Forward had passed through only three or four days before. Continuing upriver, a fisherman met the party at about 3 pm, “carrying a load of water melons; . . . [the sailors] went for the melons and also for information,” as Brownson put it. The fisherman merchant informed the party that the Forward sat twelve miles upstream and offered his services in locating it, an offer Brownson willingly accepted. Although the fisherman incorrectly assessed the distance, the party found the ship slightly after sundown, after traveling “over 40 miles” from the river’s mouth.

The engagement did not play out as expected but Brownson’s courage and quick thinking assured that the Forward would never sail the ocean again. As the party approached the steamer in two columns, a small boat attempted escape. Brownson ordered Ensign Jonathon Wainwright, commanding one of the expedition’s six boats, to seize that vessel while the remainder of the Mohican’s boats continued to the main prize. The Forward was “hard aground . . . drawing seven feet and having only five feet of water under her.” Brownson ordered his men to board, and most of the party gained the quarterdeck and encountered six men, “evidently not Mexicans.” After confirming with these men that this ship was indeed the Forward, Brownson took possession of the ship, “in the name of Captain Low, commanding the USS Mohican.” While these men – later identified as the pilot, machinist, and some firefighters – acquiesced in English, “a carbine was fired from [Wainwright’s] first cutter and almost simultaneously a volley of shell, canister, and musketry from shore raked the decks and side of the steamer.” Thankfully for Brownson, the “high bulwarks forward protected greatly the Mohican’s men.” According to Low’s later estimates, 170 men of the pirate crew waited in ambush in the forest ashore; Brownson later surmised that a sentry warned the crew of their coming while the American seamen navigated the surf at the mouth of the river. These pirates used “four 12-pounders” complemented by some sharpshooters. Nonetheless, Brownson held the deck for nearly forty minutes. While under fire, he ordered the wounded and the six prisoners moved to the boats and inspected the Forward in an effort to determine a course of action. Having already “come to the conclusion that it would be impossible, under the circumstances, to take the ship out as she was hard aground with the tide failing,” Brownson needed an alternative plan. Sailors sent below returned to report that the ship had “little or no coal in her and [that] her engines were disabled.” With this news, Brownson exclaimed to his men: “Very good. I shall burn her.” Later, Brownson explained that “after losing a man and having five more wounded, one of them Wainwright, a very dear friend, [he] didn’t feel in a very good humor.” He directed a lieutenant “to make arrangements aft in the officer quarters.” Thereafter, Brownson and a portion of his expeditionary party covered the sleeping chambers and fire room with turpentine from the Forward’s signal kit, set the ship afire, and removed to their boats, finally reaching the Mohican at 2:30 pm on 18 June with the wounded and the prisoners. Recognizing the difficulty of capturing the pirates ashore and having in any case immobilized them by destroying their ship, Brownson felt the risk was too great to try to arrest them. He thus left them in the Mexican jungle as he worked his way back to the Mohican.

The destruction of the Forward came at a significant human cost. The Mohican’s surgeon, who accompanied the expedition up the Teacapan River, reported that eight men became casualties, two of them fatal: Coxswain James Donnell died at the scene and Ensign Wainwright died of his wounds aboard the Mohican the following day. This latter loss profoundly affected both Low, who claimed Wainwright had “promise of a career valuable to the service,” and Rear Admiral Thomas Turner, commander of the Pacific Fleet, who “rarely [knew] a young officer of higher promise.” Of the six others wounded, all later recovered.

Low “delivered to Mexican authorities at Mazatlan” all the prisoners, including two Yankees, George W. Holder, “presumed to be mate,” and F. W. Johnson, “presumed to be engineer.” While Low noted that Brownson’s party had found no papers on board the Forward, at least one of these men came from San Francisco. Charles Jansen, as the owner of the ship’s charter, mentioned Holder by name later and found the mate “grossly culpable” and deserving of “little sympathy.” This demonstrates, as noted previously, that at least some of the original American crew, if not all of it, joined with Vega. Nevertheless, the prisoners would not see their day in court; in January 1871 they escaped aboard the U. S. schooner Selma while en route to Guaymas to stand trial.

Low composed his official report as he sailed back to Mazatlan. Interestingly, while taking full responsibility, he took particular care in defending his use of expensive steam running in the pursuit. Brownson’s actions, he wrote, were “vindicated by the spirit of my orders and justified by the circumstances of the case; I must consequently give it my approval.” He continued, “I trust my action in this emergency may meet with the approval of the Department [of the Navy], and that in the use of steam I may also be justified.”

Low had the support of his superior officer, the commander of the Pacific Fleet. In August 1870, en route from Peru to San Francisco, Rear Admiral Turner heard of the actions of the Mohican. After stopping at San Blas and Mazatlan, Turner concluded that Low gave a “detailed authentic account” and he found “no need of [his] commenting upon” the operations. Regarding Brownson’s expedition, Turner later noted that the lieutenant’s “action on this occasion justified my [favorable] impressions” of him.

In early September 1870 Rear Admiral Turner met with British Admiral Arthur Farquhar, Royal Navy, commander of all British warships in the Pacific. Farquhar revealed that the British also sought the Forward after the raid at Guaymas, owing to the depredation against British commerce at that port. It gave Turner much pride, and he relayed to Washington Farquhar’s quip: “this is always the way with you American Navy officers; you are ahead of us when a ship-of-war is required to be on the spot.”

After the destruction of the Forward, American policymakers attempted to sort out the culpability for the raid on Guaymas. Given the strong relationship between the United States and the Juarez government, State Department officials in Mexico remained ambivalent when it came to pressing blame even as their superiors in Washington pushed them to fault the Mexican authorities. A letter from Sisson to Nelson dated 4 June 1870 argued for disavowing Mexican culpability and in fact anticipated later American foreign policy. Though a consistent critic of Mexican lawlessness, Sisson declared that he did “not see in any evidence yet before [the United States of] any good ground for holding the Mexican government responsible for the depredation of the Forward.” Rather, no single government deserved the entire fault for the expedition because the ship flew the San Salvadorian flag, it belonged “in fact” to a Mexican citizen, an American citizen chartered it in San Francisco, and it took Mexican rebels on board at a Mexican port. The Juarez regime, he wrote, “was under no obligation to anticipate or guard against” rebels who would abscond a foreign vessel and engage in piracy, though “in this case [Mexico] seems to have done what it could.” The United States, he likewise argued, “atoned for [any negligence] by destroying the Forward at the cost of the lives of at least two gallant officers.” Nevertheless, Sisson worried about the precedent that Mexico’s “inability to protect foreigners within its jurisdiction will have,” as foreign governments would use such impotence as an excuse to invade the Latin American nation. Foreshadowing the Roosevelt Corollary of 1904 to the Monroe Doctrine, Sisson argued that such threat “will compel us, as the next neighbor – who will not allow foreign powers to seek redress by military force – to take upon ourselves the onus of establishing just an efficient government in Mexico.” Thus, while Sisson treated Mexico as an immature child, he saw “nothing . . . to warrant international sedative action.”