USS Mohican

Forward – Pirate Ship

On 17 June 1870, after forty miles and over twelve hours of exhausting oaring on the Teacapan River of western Mexico, the sixty-man expedition from the USS Mohican finally sighted their prize as the sun began to set: the pirate ship Forward. Led by Lieutenant Willard Brownson, USN, the sailors stealthily crept up on the vessel that had only the month prior ravaged the city of Guaymas, Mexico. Silently climbing on board, Brownson and some of the expedition’s party found the ship largely abandoned before a round of shot roared at them like a clap of thunder from the coast, apparently from pirates who laid in wait on shore for the seamen. The sailors quickly threw themselves against the ship’s bulwarks for safety. While still taking fire from the ambushing marauders, Brownson ordered his men to inspect the ship to see if she were moveable. Receiving intelligence that the Forward was in fact too hard aground to capture, he thus made the decision to scuttle her by emphatically declaring, “very good, I shall burn her.” Still under fire, Brownson ordered his men to collect the ship’s turpentine store and to ignite the Forward. While flame began to consume the piratical vessel, the lieutenant and his party bravely returned to their transports, eventually escaping to the safety of the Mohican at river’s mouth on the Pacific Ocean.

A more comprehensive examination of Forward’s destruction is necessary for three reasons. First, Commander William Low of the USS Mohican took it upon himself, without orders from Washington, to destroy the buccaneer ship, revealing a sense of American authority in the hemisphere that was rare, though not unheard of in the nineteenth-century U. S. Navy. Second, unlike previous U. S. naval interventions against pirates, such as those of 1819 in the waters of Venezuela and Texas, and in the early 1820s off Cuba and Puerto Rico, the attack on the Forward occurred well within foreign territory. Starting in the early morning hours of 17 June 1870, Brownson’s party pushed forty miles up the Teacapan River to accomplish its task of destroying the piratical craft. Third, in so doing, the officers and crew of the USS Mohican acted as the de facto naval authority of Mexico instead of acting solely for the interests of the United States. This diplomatic context has been most conspicuously absent from previous studies of the incident, which generally infer that Low had some high-level Mexican authority when, in fact, he did not. The Forward’s sensational demise represents an important event in American diplomatic and naval development. Naval officers, acting without orders from Washington, engaged a pirate ship in a friendly nation’s inland waters, enhancing the U. S. Navy’s prestige and amity between liberals in the two North American republics.

The Forward incident traced its beginnings to the 1864-67 civil war in Mexico. During this conflict, Benito Juarez and his liberal allies, with at least nominal support of most Western governments, had fought a guerrilla war against the French-supported Emperor Maximilian, using as their base the city of El Paseo del Norte (presently Ciudad Juarez in the state of Chihuahua). By 1867, increasing Prussian power in Europe caused French Emperor Napoleon III to recall his troops supporting Maximilian’s regime and the puppet government quickly crumbled. Ultimately, Maximilian and his two most prominent conservative Mexican allies, Miguel Miramon and Tomas Mejia, met their deaths outside Querétaro, ending the civil war and restoring Juarez to power on 19 June 1867.

During the conflict, Washington materially and politically supported the liberal Juarez regime despite the obvious handicap of fighting its own civil war against the Southern Confederacy. Materially, the United States provided weaponry and medicine to the Juarista cause. With adept political and financial supervision from the Mexican minister to the United States, Matias Romero, various U. S. and Mexican citizens were able to purchase and to ship rifles, ammunition, gunpowder, and surgical supplies to the Juaristas. Politically, given the exigencies of a concurrent civil war in the United States, the Abraham Lincoln administration could offer no more than non-recognition of Maximilian’s regime in Mexico City to aid Juarez until 1865. The effective destruction of the Confederacy in April of that year enabled U. S. diplomatic support to assume more than a token character. For example, in July 1866, President Andrew Johnson sent General William Tecumseh Sherman to Veracruz to support Juarez but the war hero could not find the Mexican president. At the same time, Johnson ordered prominent cavalry commander Phillip Sheridan to lead a large army to Texas ostensibly to maintain order and to reconstruct the wayward state. While there, Sheridan covertly aided the Juarista armies on the south side of the border by supplying them “with arms and ammunition, which [Sheridan’s army] left at convenient places on [the U. S.] side of the border to fall into [Juarista] hands,” and, furthermore, disseminated rumors that his force “was to cross the Rio Grande in behalf of the Liberal cause.” Therefore, by the time of Maximilian’s death in 1867, the liberals under Juarez had a very positive relationship with Washington and for the next nine years, U. S.-Mexican friendship arguably peaked.

Nonetheless, the return of Juarez to Mexico City in 1867 did not bring peace and prosperity to Mexico. The inability of the central government to repair quickly the countryside from the ravages of the recent guerrilla conflict, and attempts by Juarez to centralize the government, against the tenets of Mexican liberalism, caused many anti-Juarez uprisings by disenchanted liberals. One historian estimates that thirteen such local rebellions occurred between 1867 and 1870.

Certainly, such localism pervaded Mexican history in the nineteenth century and was not unique to the 1860s and early 1870s. Since at least independence in 1821, political instability bred localism, resulting in small patrias chicas (small homelands) throughout the country. The rugged men who ran these territories, caudillos, enhanced their wealth and power through forceful protection of their landed interests with armies loyal to them and occasionally on sea using hired marine mercenaries. These efforts aimed at resisting the centralization of the caudillo’s lands by the national government and thus protecting his power.

One such example of political localism after Juarez’s return, the one which would catalyze the intervention of the USS Mohican, occurred in the Pacific-coast state of Sinaloa and was led by Placido Vega, a former Juarista. Immediately before the French intervention, Vega had governed the state, but during the war against Maximilian he fled the country and worked on behalf of the Juarez government in San Francisco, California, successfully purchasing more than $600,000 in arms for the Juarista cause before returning home in 1867 after the uprising against the Hapsburg emperor succeeded. Shortly afterwards, Vega’s discontent with Mexico City ostensibly over issues of political centralization became evident. In a proclamation on 8 February 1870 at Encarnacion, Sinaloa, Vega stated his opposition to the “usurping President Juarez.” Vega acceded in principle to the Plan of Zacatecas, a different statement of rebellion against the central regime from the adjacent state of Zacatecas. He asked “the legislature and executive or the state to sustain him,” militarily and warned that if they refused, he would “assume the civil authority with extraordinary powers” and raise an army himself. When the Juarista administration in Sinaloa obviously refused to sanction Vega’s actions, he built a private army around the mouth of the Teacapan River, which at the time was the border between the states of Sinaloa and Jalisco. Vega also received the protection of the caudillo Manuel Lozada, a powerful local leader with whom the Juarez government had agreed to a truce. For nominal recognition of Juarez’s presidency, Lozada had received a pledge from Mexico City that government troops would not invade Lozada’s territory. This arrangement permitted Lozada to create a virtual fiefdom in Jalisco and provided Vega with a secure base of operations.

To supply his rebel army, Vega began a systematic campaign of coastal piracy and interior raids, according to U. S. diplomats in Mexico who kept themselves apprised of the chaotic state of affairs that Vega’s forays caused in Sinaloa. For example, the American consul at Mazatlan, Isaac Sisson, remarked on 4 March 1870 – less than a month after Vegas’s rebellious announcement – that he found the state of Sinaloa in a “deplorable condition.” The Juarista governor had fled to the mountains to raise his own army, leading Sisson to lament that “Sinaloa was never in as bad a condition.” To compound the problems, the consul reported, “Vega is coming up from Jalisco, the state south of this, to proclaim himself Governor of this State.”

On 29 March, the U. S. minister in Mexico City, Thomas Nelson, informed Washington that Vega’s expedition to Tepic, a canton in western Jalisco, “completely failed” and that Tepic “would soon be secure against invaders.” By early April, the tables had turned: “the vanguard of [Juarista] Col. Parra’s command was defeated by a rebel force under Placido Vega . . . at a point in Sinaloa about a hundred miles from Mazatlan, and at the latest advices Vega was advancing toward” the important coastal port. The tide again changed and in early May Nelson reported that the entire rebellion “has resulted in complete failure and that [Vega’s] troops have been dispersed”; this coupled with incorrect news “that the intrepid bandit died recently at Tepic,” greatly encouraged Nelson.

Meanwhile, Alexander Willard, U. S. Consul in Guaymas, Sonora, warned that Vega was planning a new offensive. “[T]here is . . . a faction in this state that await only the success of the revolutionary movement of General Vega in the states of Sinaloa and Jalisco to develop into a political party,” Willard reported on 31 March 1870. That faction would thereafter “declare themselves in his favor under the pretext of saving this country `from the iniquitous compact’ which President Juarez (so they report) is about to make with the United States, to despoil and rob Mexico of her territory.” Willard reported that Vega “must first demonstrate that he has the means at his command and the ability as a soldier . . . before the state of Sonora will render to his movement any tangible assistance.” Given that Vega’s inland campaigns had failed – as Nelson reported – it was not surprising that the rebel began to focus on coastal raids to curry support in the state of Sonora. What Vega did not realize was that his actions would ultimately lead to the involvement of the United States Navy.

By the middle of May 1870, American officials suspected that Vega planned to move beyond the area of Tepic, where the Mexican army kept his forces in check and his supplies limited, and embark upon a maritime expedition. In Mexico City, Nelson received information from Tepic that the citizens of that town planned “to extricate themselves from the difficulties occasioned by Placido Vega” and that Vega aimed to “attack the State of Sinaloa at another point, perhaps in the neighborhood of El Fuerte,” a city a few miles inland in northern Sinaloa, near the Sonoran border. Given the overland distance to El Fuerte, Nelson’s anonymous purveyor of intelligence astutely expected a maritime expedition, noting that Vega had “a steamer and a sailing vessel at his disposal, but his force is small, and it seems his only hope is that his friends [at El Fuerte] may render him some assistance.”

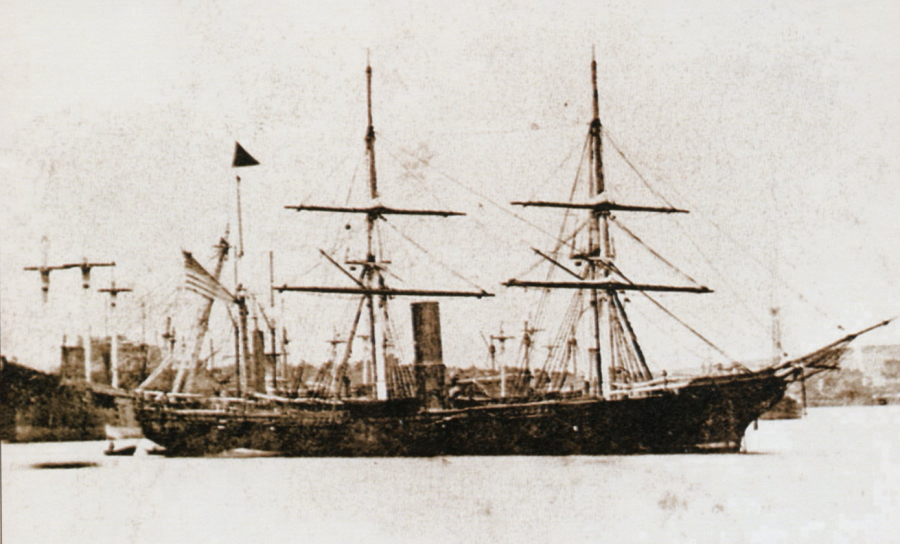

The steamer Forward originally sailed under the British flag, until San Francisco merchant James Maule purchased the ship and registered it in San Salvador. He chartered it on 4 January 1870 to San Francisco merchant Charles Jansen and a few days later Forward left San Francisco for Mazatlan under the command of Captain James Jones on “a legitimate voyage” according to Jansen’s later testimony. The charter agreement was for “the term of twelve months [for] fishing, trading, [and] freighting . . . to and from ports or places on the coast of the Republic of Mexico, and . . . ports and places on the Pacific coast of the United States of America.” On 24 March, the ship docked at Mazatlan, where the Juarista authorities, suspecting collusion with the Vega rebellion, detained it and its captain for three weeks, making sure to take “some of her machinery and a portion of her sails” ashore “to prevent her escape.” The Juaristas found nothing to implicate the ship or its crew and allowed it to sail south to San Blas, where Jones received a permit to fish for oysters at the mouth of the nearby Teacapan River.

There, in the center of Vega’s power, the Forward became a pirate vessel after Juarista authorities arrested Captain Jones. Apparently, Captain Jones had anchored the ship at the mouth of the river for three days in late April when a local Juarista military officer Jesus Vega, of no relation to Placido Vega, ordered the Forward into port. Jesus Vega arrested the American captain, arguing that Jones took “cannon on board at San Blas and landed them at Boca Teacapan for Placido Vega.” Jones posted a three-thousand dollar bond and remained free in Mazatlan while awaiting trial. Meanwhile the steamer suddenly left port for an unknown destination and became a pirate ship.

Since the ship engaged in piracy after its sudden captain-less departure, Jones’s arrest helps clarify who among the various parties involved, Jesus Vega, the captain, and the crew, may have colluded with the rebels, facts of vital importance after the burning of the Forward. Because Jesus Vega turned Jones over to authorities in Mazatlan, a Juarista stronghold, one can assume that he was a firm Juarista acting on what he believed to be correct intelligence as to the ship’s mission. The validity of the intelligence, of course, remains in doubt.

Captain Jones’s role is less clear. While Jones protested his March 1870 detention in Mazatlan “one, twice, thrice, and as many times as may be necessary,” this does not prove or disprove his complicity in the plot. Quite possibly, the second arrest by Jesus Vega in April thwarted Jones in joining with the rebels. Alternatively, Jones may not have intended to participate in the plot and in that case Placido Vega’s men may have circulated false intelligence in order to have him removed from the Forward. Finally, Jones may have been oblivious to any plot and his arrest may have been a simple stroke of luck for the rebels. In any event, though the Mazatlan authorities viewed Jones “as a friend of Vega,” they did not have the “proofs sufficient to make it clear” and the Mexican officials officially acquitted him of any wrong-doing and released him by November 1870. Historians, working with a different set of evidence, need not heed judicial determinations or assumed culpability.

Circumstantial evidence strongly suggests that at least part of the original American crew engaged in the later piracy. First, the consul at Mazatlan wrote that the Forward had an “oar crew of Americans, Germans, and Mexicans.” Second, when Lieutenant Brownson boarded the ship after its capture he noted that, among those taken prisoner, he “saw six men standing there, evidently not Mexicans” some of whom spoke colloquial English. Third, Consul Willard in Guaymas later noted that of these six captured, “two . . . claimed to be native-born citizens of the U. S. and three . . . claimed to have been naturalized.” Fourth, the ship originally sailed from San Francisco, Vega’s base during the fight against Maximilian. This body of evidence does not preclude that new Americans joined the expedition at some point, replacing the original San Francisco crew. Evidence that at least one member of the original crew was in the piratical party arose only after the capture of part of the Forward’s crew with evidence from Jansen that he employed one of the six prisoners taken in the raid, George Holder. That fact would play a very important role in determining who later assumed blame for the May 1870 raid on Guaymas.

What is beyond dispute is that when the Forward next appeared, at Guaymas on 28 May 1870, she was under the command of the rebel Vega’s forces. It was the vessel’s actions at Guaymas that prompted the United States Navy to act as an agent of a foreign power.

Placido Vega clearly ordered the raid on Guaymas in late May 1870, about a month after the Forward’s first detention in Mazatlan. In written instructions dated 18 May 1870 from the mouth of the Teacapan River, which Vega later sent to Mexican newspapers and Nelson forwarded to Washington, the rebel leader gave his subordinate Fortino Vizcayno a very specific plan of attack against the coastal town. Calling himself the “Commander in Chief” of the “Division of Sinaloa,” Vega ordered Vizcayno to accomplish four specific tasks and to complete them with “the well known good conduct of the force under your command.” First, after coming ashore, Vizcayno should obtain “two hundred and eight cases, containing five thousand Prussian rifles” sent to him from San Francisco aboard the American schooner Montana but which the “arbitrary” Juarez government forbid Vega to collect from the customs house. Second, Vizcayno should “impose without fail a forced loan of four hundred thousand dollars” from the local merchant houses and to obtain “corresponding receipts . . . signed by the Paymaster Citizen Ignacio Carreau.” Third, Vega ordered Vizcayno to conscript “the greatest number of men possible.” Finally, “if the circumstances of [the] expedition permit it,” Vizcayno should attempt to “land at the port of La Paz (Baja California) . . . [and] impose a loan of thirty thousand dollars.”

Vizcayno did not delay and left the mouth of the San Pedro River aboard the Forward soon after these instructions. He “touched at the islands of Maria,” off the coast of Jalisco, where his men “carried off the workmen who were employed by Don C. Villaseñor” in the salt mines. He continued north thereafter.

Once arriving at Guaymas, Vizcayno followed dutifully Vega’s instructions and carried out other acts of piracy. On the evening of 27 May 1870, fishermen reported the Forward six miles offshore from the Sonoran port. At 3 am on 28 May, an expeditionary party led by Vizcayno “entered the city taking it by surprise, without opposition, taking on board the collector of customs and his officers and the Jefe de Hacienda Lic[enciado] Alfonso Mejia, and almost all of the local authorities,” according to the U. S. consul. Immediately, Vizcayno’s party forced loans from the local merchants, collected only approximately $42,000 from the house of Ortiz Hermanos, obtained receipts for this money from the kidnapped customs collector, and “seized two Mexican vessels laying in port.” Afterwards, the party requisitioned the five thousand muskets, which U. S. Consul Willard reported were “brought [to Guaymas] originally for the Mexican government, but not accepted.” Later in the day, the Forward itself came into port and Vizcayno requisitioned “some fifty odd tons of coal, the property of the California line of steamers,” telling Willard that “urgent necessity compelled the seizure, but [Vizcayno] would pay $40.00 per ton, double the market value,” for the fuel. The following morning, 29 May, Vizcayno paid for the coal. Upon seeing government troops entering the city at 3 pm, Vizcayno’s crew prepared for its departure, “evidently wishing to avoid an attack . . . as all of the money due the Customs House from the merchants had been collected.” They embarked at 8 pm with the two seized vessels and government forces retook the city two hours later.