During the opening attacks of the 1967 Six Day War, the Israeli Air Force struck Arab air forces in four attack waves. In the first wave, IDF aircraft claimed to have destroyed eight Egyptian aircraft in air-to-air combat, of which seven were MiG-21s; Egypt claimed five kills scored by MiG-21PFs. During the second wave Israel claimed four MiG-21s downed in air-to-air combat, and the third wave resulted in two Syrian and one Iraqi MiG-21s claimed destroyed in the air. The fourth wave destroyed many more Syrian MiG-21s on the ground. Overall, Egypt lost around 100 out of about 110 MiG-21s they had, almost all on the ground; Syria lost 35 of 60 MiG-21F-13s and MiG-21PFs in the air and on the ground.

Between the end of the Six Day War and the start of the War of Attrition, IDF Mirage fighters had six confirmed kills of Egyptian MiG-21s, in exchange for Egyptian MiG-21s scoring two confirmed and three probable kills against Israeli aircraft. During the War of Attrition itself, Israel claimed 56 confirmed kills[citation needed] against Egyptian MiG-21s, while Egyptian MiG-21s claimed 14 confirmed and 12 probable kills against IDF aircraft. During this same time period, from the end of the Six Day War to the end of the War of Attrition, Israel claimed a total of 25 Syrian MiG-21s destroyed; the Syrians claimed three confirmed and four probable kills of Israel aircraft.

High losses to Egyptian aircraft and continuous bombing during the War of Attrition caused Egypt to ask the Soviet Union for help. In June 1970, Soviet pilots and SAM crews arrived with their equipment. On 22 June 1970, a Soviet pilot flying a MiG-21MF shot down an Israeli A-4E. After some more successful intercepts by Soviet pilots and another Israeli A-4 being shot down on 25 July, Israel decided to plan an ambush in response. On 30 July Israeli F-4s lured Soviet MiG-21s into an area where they were ambushed by Mirages. Asher Snir, flying a Mirage IIICJ, destroyed a Soviet MiG-21; Avihu Ben-Nun and Aviam Sela, both piloting F-4Es, each got a kill, and an unidentified pilot in another Mirage scored the fourth kill against the Soviet-flown MiG-21s. Three Soviet pilots were killed and the Soviet Union was alarmed by the losses. However, Soviet MiG-21 pilots and SAM crews destroyed a total of 21 Israeli aircraft, which helped to convince the Israelis to sign a ceasefire agreement.

In September 1973, a large air battle erupted between Syria and Israel; Israel claimed a total of 12 Syrian MiG-21s destroyed, while Syria claimed eight kills scored by MiG-21s and admitted five losses.

During the Yom Kippur War, Israel claimed 73 kills against Egyptian MiG-21s (65 confirmed). Egypt claimed 27 confirmed kills against Israeli aircraft by its MiG-21s, plus eight probables. However, according to most Israeli sources, these were exaggerated claims as Israeli air-to-air combat losses for the entire war did not exceed five to fifteen.

On the Syrian front of the war, 6 October 1973 saw a flight of Syrian MiG-21MFs shoot down an IDF A-4E and a Mirage IIICJ while losing three of their own to Israeli IAI Neshers. On 7 October, Syrian MiG-21MFs downed two Israeli F-4Es, three Mirage IIICJs and an A-4E while losing two of their MiGs to Neshers and one to an F-4E, plus two to friendly SAM fire. Iraqi MiG-21PFs also operated on this front, and on that same day destroyed two A-4Es while losing one MiG. On 8 October 1973, Syrian MiG-21PFMs downed three F-4Es, but six of their MiG-21s were lost. By the end of the war, Syrian MiG-21s claimed a total of 30 confirmed kills against Israeli aircraft; 29 MiG-21s were claimed (26 confirmed) as destroyed by the IDF.

Between the end of the Yom Kippur War and the start of the 1982 Lebanon War, Israel had received modern F-15s and F-16s, which were far superior to the old Syrian MiG-21MFs. According to the IDF, these new aircraft accounted for the destruction of 24 Syrian MiG-21s over this time period, though Syria did claim five kills against IDF aircraft with their MiG-21s armed with outdated K-13 missiles.

The 1982 Lebanon War started on 6 June 1982, and in the course of that war the IDF claimed to have destroyed about 45 Syrian MiG-21MFs. Syria claimed two confirmed and 15 probable kills of Israeli aircraft. In addition, at least two Israeli F-15 and one F-4 was damaged in combat with the MiG-21. This air battle was the largest to occur since the Korean War.

Egyptian Air-to-Air Victories since 1948

Both the Arab and Israeli purchase of Mach 2 fighters shared one common feature – the acquired type was not selected following an exhaustive competitive or evaluative process. The MiG-21 and Mirage IIIC were simply offered by the USSR and France, respectively, on a “take it or leave it” basis, as no other Mach 2-capable combat aircraft were then available to the Arab nations or Israel.

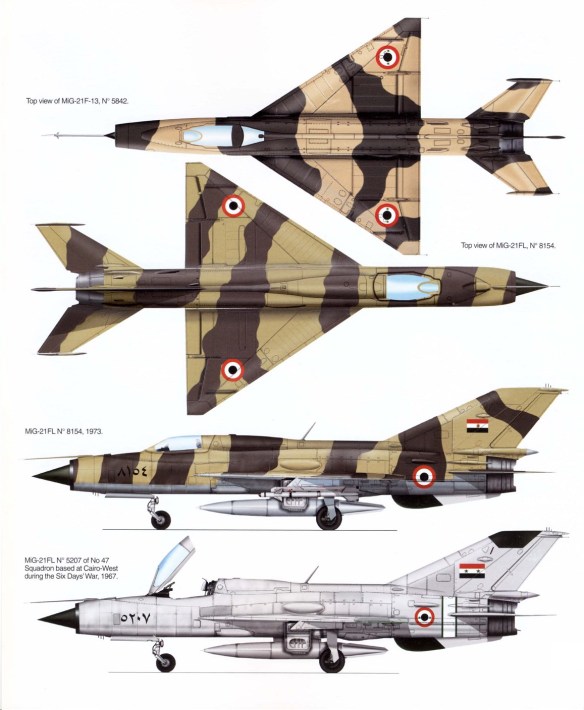

Initially at least, the Egyptian acquisition of the MiG-21F ran in parallel to the Israeli procurement of the Mirage IIICJ. As IDF/AF pilots were converting onto their new fighter in France in 1961, so their EAF counterparts were undertaking a MiG-21 conversion course in Soviet-controlled Kazakhstan. Deliveries of Shahaks to Israel commenced in April 1962, with the first of 50 MiG-21F-13s reaching Egypt the following month. There were differences, however. While the IDF/AF equipped its fighter squadrons with 24 aircraft, the standard EAF unit was issued with just 15 jets. Like the Israelis, the Egyptians equipped three squadrons with the new fighter, two of them being based at Inshas, in the Nile Delta, and one at Cairo West – all three were reportedly subordinated to a single air brigade.

The EAF and IDF/AF also differed in respect to their organisation, as the Israelis did not divide their airspace up into zones of responsibility or have units that were the equivalent of Egyptian air brigades. The IDF/AF had only squadrons and air bases. The latter were administrative units in their own right in charge of the day-to-day running of the squadrons assigned to them, as well as base defence and logistics. However, the squadrons received their operational orders from IDF/AF headquarters, as it directly controlled all missions. The EAF’s organisational structure was more complex. Although its bases functioned in a similar way administratively to their IDF/AF counterparts, the overall chain of command also included air zones and air brigades. EAF headquarters issued orders to air zones, which in turn passed them on to air brigades. To further complicate things, a MiG-21 squadron flying from one base could be subordinated to an air brigade with headquarters at another air base.

Egyptian MiG-21F-13 acquisition continued into 1964, and in January of that year IDF/AF Intelligence stated that the EAF’s order of battle included 60 “Fishbed-Cs”. Elsewhere in the Middle East, both Iraq and Syria had received MiG-21F-13s by 1964. The IrAF would eventually take delivery of 60 “Fishbed-Cs”. Finally, the Algerians also started to receive a small number of MiG-21F-13s from 1965. An updated IDF/AF Intelligence evaluation from April of that year reported Egyptian MiG-21 strength at 60 aircraft, with 30 more in Syria and 16 in Iraq. The numerical balance of power in April 1965 was, therefore, with the Arab nations, who could field 106 MiG-21s versus 67 Shahaks. The EAF activated No 40 Sqn in March 1965 at Abu Sueir, this unit becoming Egypt’s fourth MiG-21 squadron.

Arab pilots praised their MiG-21F-13s for sheer performance and robust reliability. They were critical of its limited range and austere weapon system, however – both faults that also afflicted the Shahak. The MiG-21F-13’s firepower consisted of just two infrared-homing R-3S “Atoll” AAMs and a single 30mm cannon that only had enough ammunition to be fired for about two seconds. The combination of these weapons gave the “Fishbed-C” a theoretical engagement range of two miles down to 100 metres.

The two Mach 2 fighters shared comparable performance, and except for the MiG-21’s all-moving horizontal tailplanes, they both had a similar delta wing configuration. The horizontal tailplanes increased the wing loading for the Soviet fighter, however, despite it being lighter than the Mirage III. This in turn meant that the French aircraft enjoyed superior sustained performance in a dogfight, most prominently in horizontal manoeuvring. Thanks to its light weight, the MiG-21 had a better thrust-to-weight ratio, giving it an advantage in vertical manoeuvring.

In respect to the fighters’ internal fuel capacity, the MiG-21F-13 and Mirage IIICJ were closely matched at 2,480 litres and 2,550 litres, respectively. The Shahak had greater combat persistence though thanks to its three-missile/twin-gun armament, the latter capable of firing twice as many rounds from the larger magazine fitted in the fighter’s gun pack. The Shahak’s superiority in this area increased still further with the introduction of the MiG-21FL in the Middle East. The latter was slightly heavier than the MiG-21F-13 thanks to its improved avionics (primarily an RP-21 Spfir (Sapphire) AI radar), so the Soviet fighter’s marginal thrust-to-weight ratio advantage over the Shahak disappeared.

Egypt received the first of its 45 to 50 MiG-21FLs in 1965, and these reached operational status the following year. The designation FL was used both by an export version of the MiG-21PFM and a variant manufactured in India. However, the PFM and the Indian-built FL had a twin-barrelled Gsh-23 23mm cannon in an externally mounted pod beneath the fuselage. The MiG-21FLs in Egypt were not fitted with these pods until after the Six Day War, being solely armed with a pair of heat-seeking R-3S missiles. They could more properly be designated MiG-21PFs. In most respects the PF was even less suited to the kind of fighting involving Arab pilots than the MiG-21F-13, which at least had reasonably good cockpit visibility and a powerful 30mm cannon. In fact they came to be seen as a disaster for the Arab air arms that flew them in 1967.