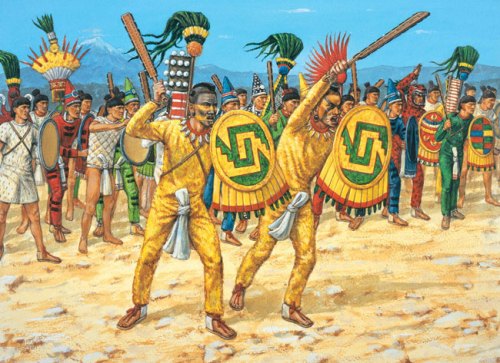

The Aztecs, who became established in central Mexico in the early 1300s and whose empire flourished from 1430 to 1521, made the last major weapons innovations. Under their empire, a preindustrial military complex supplied the imperial center with materials not available locally, or manufactured elsewhere. The main Aztec projectiles were arrows shot from bows and darts shot from atlatls, augmented by slingers. Arrows could reach well over a hundred meters-and sling stones much farther-but the effective range of atlatl darts (as mentioned earlier, about 60 meters) limited the beginning of all barrages to that range. The principle shock weapons were long, straight oak broadswords with obsidian blades glued into grooves on both sides, and thrusting spears with bladed extended heads. These arms culminated a long developmental history in which faster, lighter arms with increasingly greater cutting surface were substituted for slower, heavier crushing weapons. Knives persisted, but were used principally for the coup de grace. Armor consisted of quilted cotton jerkins, covering only the trunk of the body, leaving limbs unencumbered and the head free, which could be covered by a full suit of feathers or leather according to accomplishment. Warriors also carried 60-centimeter round shields on the left wrist. Where cotton was scarce, maguey (fiber from agave plants) was also fabricated into armor, but the long, straight fiber lacked the resilience and warmth of cotton. In west Mexico, where clubs and maces persisted, warriors protected themselves with barrel armor-a cylindrical body encasement presumably made of leather.

City walls and hilltop strongholds continued into Aztec times, but construction limitations rendered it too costly to enclose large areas. Built in a lake, the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan lacked the need for extensive defenses, though the causeways that linked it to the shore had both fortifications and removable wooden bridges.

By Aztec times, if not far earlier, chili fi res were used to smoke out fortified defenders, provided the wind cooperated. Poisons were known, but not used in battle, so blowguns were relegated to birding and sport. Where there were sizable bodies of water, battles were fought from rafts and canoes. More importantly, especially in the Valley of Mexico, canoe transports were crucial for deploying soldiers quickly and efficiently throughout the lake system. By the time of the Spanish conquest, some canoes were armored with wooden defensive works that were impermeable to projectiles.

The Importance of Organization

Despite the great emphasis placed on weaponry, perhaps the most crucial element in warfare in Mesoamerica was organization. Marshaling, dispatching, and supplying an army of considerable size for any distance or duration required great planning and coordination. Human porters bearing supplies accompanied armies in the vanguard (the body of the army); tribute empires were organized to maintain roads and provide foodstuffs to armies en route, allowing imperial forces to travel farther and faster than their opponents; and cartographers mapped out routes, nightly stops, obstacles, and water sources to permit the march and coordinate the timely meeting of multiple armies at the target.

What distinguished Mexican imperial combat from combat in North America was less technological than organizational. More effective weapons are less important than disciplining an army to sustain an assault in the face of opposition; that task requires a political structure capable not merely of training soldiers, but of punishing them if they fail to carry out commands. Polities with the power to execute soldiers for disobedience emerged in Mexico but not in North America; those polities had a decisive advantage over their competitors.

In North America, chiefdoms dominated the Southeast beginning after 900 CE, and wars were waged for status and political domination, but the chiefdoms of the Southwest had disintegrated after 1200 CE, and pueblos had emerged from the wreckage. (We use the term pueblos to refer to the settled tribal communities of the Southwest, but chiefdom is a political term that reflects the power of the chief, which was greater than that exercised by the puebloan societies after the collapse around 1200 CE.) There too warfare played a role, though for the pueblos wars were often defensive engagements against increasing numbers of nomadic groups. The golden age of North American Indian warfare emerged only after the arrival of Europeans, their arms, and horses. But even then, in the absence of Mesoamerican-style centralized political authority, individual goals, surprise attacks, and hit-and-run tactics dominated the battlefield, not sustained combat in the face of determined opposition.

Further Reading Andreski, S. (1968). Military organization and society. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. Ferguson, R. B., & Whitehead, N. L. (1992). War in the tribal zone: Expanding states and indigenous warfare. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press. Hassig, R. (1988). Aztec warfare: Imperial expansion and political control. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. Hassig, R. (1992). War and society in ancient Mesoamerica. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. Hassig, R. (1994). Mexico and the Spanish conquest. London: Longman Group. LeBlanc, S. A. (1999). Prehistoric warfare in the American southwest. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. Otterbein, K. F. (1970). The evolution of war: A cross-cultural study. New Haven, CT: HRAF Press. Pauketat, T. (1999). America’s ancient warriors. MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, 11(3), 50-55. Turney-High, H. H. (1971). Primitive war: Its practice and concepts. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. Van Creveld, M. (1989). Technology and war: From 2000 b. c. to the present. New York: The Free Press