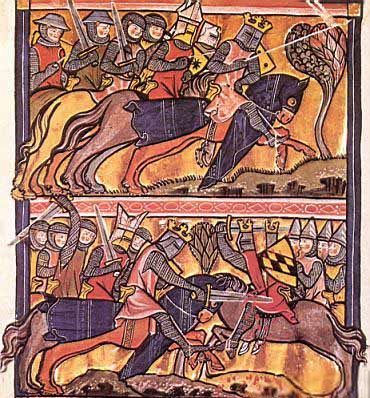

The Vita Caroli Magni of the lat e 13th century relates the life of Charlemagne and portrays the church militant In the form of Archbishop Turpins. His crest of a mitre seems to have a cloth mantling hanging down at the rear, which wafts out behind, though the other helms have a plate over this area which is presumably a reinforce. No surviving helm shows this feature, questionable since any reinforces are usually added to the front.

Warrior bishops were present as early as the tenth century, as can be seen by Otto the Great’s commitment of his bishops to the German empire for military purposes. When discussing medieval bishops and priests, one envisions saintly individuals in ecclesiastical robes, providing prayer or preaching to their flocks. However, bishops and archbishops could be seen leading their own retinues into battle, sometimes in full armour.

In 1124, Henry V found that many Germans refused to join his advance into France because they were not keen to fight foreigners. Though the personal retinues of those attending a diet (parliament) in 1235 were recorded at 12,000 knights, in reality the imperial army often had to rely more on the forces of the church. Ecclesiastics did not hold allodial land, having it rather by imperial decree. Their services were not feudal, however. From the revenues of these estates they were expected to find and finance a specific number of troops, a burden which sometimes left them pawning or mortgaging their land or goods. Many abbots, bishops and archbishops were military leaders and could be seen at the head of their men. Their importance to the emperor may be seen from the fact that, in 1046, Emperor Henry III invaded Italy with three archbishops, ten bishops and two abbots.

The following examples are worth noting, as they demonstrate the conflict that sometimes seemed to be inherent in calling upon spiritual leaders to perform acts of destructive warfare. In 1003, Henry II sent Bishop Henry of Würzburg and Abbot Erkenbald of Fulda to destroy Schweinfurt to punish its rebel lord, the Margrave Henry. When Henry’s agitated mother refused to leave, the two churchmen “…[put] aside secular concerns in favor of the love of Christ,” and instead did only token damage. On the other hand, Bishops Arnulf of Halberstadt and Meinwerk of Paderborn, among others, were ordered by Henry II to pillage Polish territory during his expedition against Boleslav Chrobry in 1010: “And so it was done,” without elaboration. Archbishop Gero of Magdeburg was co-commander of Henry’s rearguard towards the close of the Polish campaign of 1015. His force suffered heavy casualties and while he himself managed to escape, he found himself in the melancholy position of having to officiate at the funerals of some of his fellow nobles who did not. Archbishop Tagino of Merseburg, who sponsored Thietmar to succeed him in his see, commanded a force against Boleslav during the fighting of 1007.

The most memorable instances of ecclesiastical magnates participating in warfare, of course, were those in which they were not only nominally in charge of a body of men but were involved in the thick of combat themselves. While this may be implied by the number of times a bishop or abbot is cited as the leader of a military unit, unambiguous descriptions of these men putting themselves directly in harm’s way are rare. The unarmed leadership showed by Udalrich in the defense of Augsburg is a good example, as is the case of Bernward of Hildesheim during the Roman uprising against Otto III. Thietmar described a similar action during the fight against the Slavs at Bardengau in 997: “Bishop Ramward of Minden took part in that battle. Followed by the standard-bearers, he had taken up his cross in his hands and ridden out ahead of his companions, aftermath of a defeat on the Hungarian frontier. The passage is vivid and evocative:

The bishop lost an ear, was also wounded in his other limbs, and lay among the fallen as if he were dead. Lying next to him was an enemy warrior. When he realized the bishop alone was alive, and feeling safe from the snares of the enemy, he took a lance and tried to kill him. Strengthened by the Lord, the bishop emerged victorious from the long, difficult struggle and killed his enemy. Finally, travelling by various rough paths, he arrived safely in familiar territory, to the great joy of his flock and all Christians. He was held to be a brave warrior by all the clergy and the best of pastors by the people, and his mutilation brought him no shame, but rather greater honour.

This vignette has frequently been cited as proof positive of the martial nature of Ottonian bishops.

It was Archbishop Aribert of Milan who introduced the carroccio, an ox-drawn cart bearing the standard of St Ambrose. A rallying post with its own guard, it was a disgrace to lose it to an enemy. The idea was taken up by many Italian cities and was seen occasionally in Germany and elsewhere.

A mid-12th century document concerning the Archbishop of Cologne’s men provides a small insight into the services of ministeriales. ‘Whether or not they were enfeoffed knights, they were expected to defend the archbishop ‘s lands, though beyond his boundaries they expected payment if they did not agree to se1ve voluntarily. Ministeriales holding a fief with five marks’ income should go over me Alps with their lord for the coronation of me king. However the archbishop not only had to give advance warning of a year and a day, he also had to provide each man with 10 marks and 40 ells of cloth for equipment, plus a saddled packhorse, two travelling bags, four horseshoes and 24 nails four every two men. Once at the Alps each man received one mark per month for the duration of the journey. If payment was not forthcoming on time, the ministeriaJis was freed. Ministeriales with lower incomes could opt to stay behind, but had to pay an indemnity equal to half their fief’s revenue.