German submarine designs exerted a major influence, either directly or indirectly, on most of the world’s submarine development in the years between the two world wars-except in Britain and, to a lesser extent, the Soviet Union. All the major navies of the victorious Allies-Britain, France, Italy, Japan, and the United States-received examples of the latest German U-boats under the terms of the Armistice and the Treaty of Versailles. They intently examined and analyzed these German craft to determine the applicability and suitability of their features for incorporation into their own types and, in several instances, commissioned former German submarines into their own services to acquire operational experience in their use. Both Italian and French designers were very much influenced by studying and operating examples of the later Mittel-U and UB-III types prior to developing their first new postwar boats. The big U-cruisers had even more impact. The first French oceangoing submarines, the Requin class, benefited substantially from their designers’ study of U-cruisers. The big U. S. Navy fleet boats owed a great debt to the German boats (including even their diesel engines, in some cases), and German engineers were intimately involved in the development of the early Japanese kaidai and junsen types.

German design influence spread to lesser fleets too, largely through the activities of the Ingenieurskantoor voor Scheepsbouw (IvS). The IvS was established in July 1922 at Den Haag in The Netherlands by a consortium of the Krupp and Vulcan shipbuilding yards to circumvent the Versailles Treaty’s prohibition on submarine design and construction. The engineering staff was led by Hans Techel, who had headed Krupp’s submarine design team since 1907, and the firm also received clandestine financial support from the German Navy, which was desirous of maintaining German submarine design expertise despite the treaty. IvS engineers produced submarine designs that were constructed for Turkey, Finland, the Soviet Union, Spain, and Sweden, and also served as prototypes for the German Navy’s Type IIA coastal, Type IA long-range, and Type VII oceangoing U-boats.

German submarines were developed clandestinely, inasmuch as the Versailles Treaty prohibited them in the German Navy. Design work, both at IvS and by the Blohm und Voss firm, continued for foreign navies with production undertaken in the customer’s yards under German supervision. These boats also served as prototypes for domestic production, which made it possible for the first new German submarine, the U-1, to be completed on 29 June 1935, only five weeks after the repudiation of the Versailles Treaty.

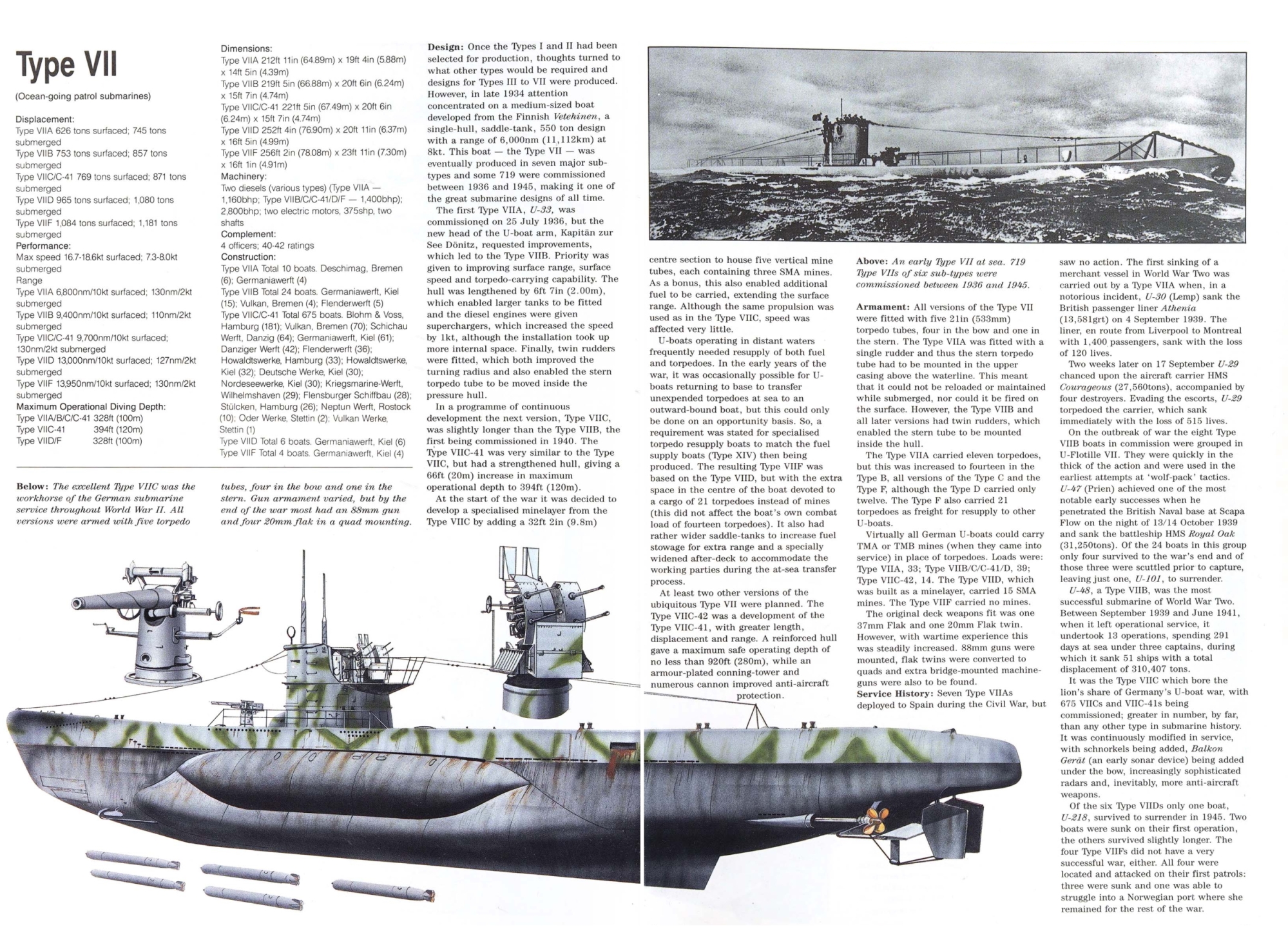

The overwhelming majority of the 1,150 U-boats commissioned between 1935 and 1945 belonged to two groups: the so-called 500- ton Type VII medium boats, and the 740-ton Type IX long-range submarines. The Type VIIC actually displaced between 760 and 1,000 tons on the surface, had a cruising range of 6,500 to 10,000 miles at 12 knots on the surface and 80 miles at 4 knots submerged. They had a battery of 5 torpedo tubes with 14 torpedoes, an 88mm deck gun, and ever-increasing numbers of light antiaircraft weapons. Almost 700 of these boats in all of their variants entered service during World War II. The Type XIC actually displaced 1,120 tons; it had a cruising range of 11,000 miles at 12 knots on the surface and 63 miles at 4 knots submerged. They had a battery of 6 torpedo tubes with 22 torpedoes, a 105mm deck gun, and ever-increasing numbers of light antiaircraft weapons. Almost 200 of this type and its variants were commissioned.

Germany also commissioned a number of other important types during World War II. Among the most important were the Type X minelayers and the Type XIV supply boats. Both types operated as resuppliers for the operational boats during the Battle of the Atlantic, providing fuel, provisions, medical supplies, reload torpedoes, and even medical care and replacement crew members. Consequently they became prime targets for Allied antisubmarine forces, and few survived. The other major vessels were the radical Type XXI and Type XXIII boats, designed for high submerged speed and extended underwater operation. Revolutionary streamlined hull shapes, greatly increased battery space, and the installation of snorkels allowed these boats to operate at submerged speeds that made them very difficult targets for Allied antisubmarine forces. Confused production priorities, however, and the general shortage of materials late in the war prevented more than a very few from putting to sea operationally.

AXIS SUBMARINE OPERATIONS

The outbreak of World War II found the German submarine arm well trained but deficient in numbers. From the moment of its reestablishment, the submarine force had concentrated much of its effort on validating Kommodore Karl Dönitz’s concepts for an all-out assault on enemy trade using concentrated groups of submarines under central shore-based control to locate and destroy convoyed shipping, primarily through surfaced night attacks (wolf-pack tactics). Dönitz was promoted Konteradmiral in October 1939, but shortages of U-boats, Adolf Hitler’s initial insistence on Germany’s adherence to the Prize Regulations, and demands on the submarine force for its support of surface naval operations prevented him from exploiting the potential of the wolf-pack tactics for most of the first nine months of the conflict. On average only six boats were at sea at any one time during this period, forcing them to attack individually, although some attempts were made to mount combined attacks whenever possible.

As a result of its World War I experience after 1917, Britain was quick to begin the convoying of merchant vessels. There was some initial hesitation because of the feared detrimental effect that convoys could have on the efficient employment of shipping, but when the liner Athena was torpedoed and sunk without warning on 3 September 1939, Britain took this to indicate that Germany had commenced an unrestricted campaign of submarine warfare against merchant vessels. Regular east coast convoys between the Firth of Forth and the River Thames started on 6 September and outbound transatlantic convoys from Liverpool two days later.

The conquest of Norway and the collapse of France in June 1940 brought substantial changes to the U-boat war against trade. From French bases, German reconnaissance and long-range bomber aircraft operated far into the Atlantic, while the operational range of the U-boats sailing from Norway and French Biscay ports increased dramatically. Italy’s simultaneous entry into the war terminated all commercial traffic in the Mediterranean except for very heavily escorted operational convoys bringing supplies into Malta. It also substantially increased the number of submarines available for the Atlantic campaign against shipping, inasmuch as Italian submarines began operating from Biscay ports, effectively doubling the total Axis force at sea. This situation allowed Dönitz to introduce his wolf-pack tactic on a large scale into the Atlantic shipping campaign, just as the British faced an alarming shortage of oceanic convoy escorts because of the neutralization of the French Fleet and their decision to retain destroyers in home waters to guard against a German invasion. The results vindicated Dönitz’s belief in the effectiveness of wolf packs. In the first nine months of the war, German U-boats sank a little more than 1 million tons of shipping, whereas they and the Italians together destroyed more than 2.3 million tons between June 1940 and February 1941. However, the release of destroyers from their guard duties, the addition of new escorts, and the transfer of fifty obsolete destroyers from the U. S. Navy improved the situation. The dispersal point for westbound transatlantic convoys and the pickup point for escort groups meeting eastbound shipping gradually moved westward as the range of the escorts was increased. This pushed the main arena of Axis submarine operations more toward the mid-Atlantic zone, which reduced the time that boats could spend on station. In mid-1941 the United States imposed its socalled Neutrality Zone on the western Atlantic and began escorting British convoys in conjunction with Royal Canadian Navy escorts, operating from Argentia in Newfoundland. North Atlantic convoys now were escorted throughout by antisubmarine vessels. Nevertheless, these additions to the escort force had only a limited impact on losses, since German and Italian submarines succeeded in sinking a further 1.8 million tons in the following nine months prior to the U. S. entry into the war.

The German declaration of war on the United States on 10 December 1941 brought a major westward expansion of U-boat operations against shipping. A disastrous period followed, while the U. S. Navy struggled with the problems of finding the escorts and crews required to convoy the enormous volume of merchant traffic along the East Coast of the United States, and with the very concept of convoy itself. Axis submarines sank more than 3 million tons of Allied shipping between December 1941 and June 1942, well over 75 percent of it along the East Coast of the United States and Canada. Nevertheless, by mid-1942 an elaborate and comprehensive system of interlocking convoy routes and sailings was established for the East Coast of North America and the Caribbean.

As Dönitz became aware of the extension of convoy along the Atlantic East Coast, he shifted U-boat operations back to the mid-Atlantic. His all-out assault on the North Atlantic convoy systems inflicted heavy losses: between July 1942 and March 1943, Axis (almost entirely German) submarines destroyed more than 4.5 millions tons of Allied shipping, over 633,000 tons in March alone. Nevertheless, new Allied countermeasures became available at this crucial moment, and U-boat successes fell to 287,137 tons in April, 237,182 tons in May, and only 76,090 tons in June. Dönitz’s reaction was to deploy his U-boats in areas where Allied antisubmarine forces were weak, anticipating that this would compensate for the lack of success in the North Atlantic. Initially this plan to some extent met his expectations, since sinkings rose to 237,777 tons in July, but the success of the Allied assault on U-boats in transit to their patrol stations rendered the German accomplishment transitory; merchant ship sinkings dropped to 92,443 tons in August, never to surpass 100,000 tons per month at any subsequent time during the war.

The collapse of the U-boat offensive in mid-1943 resulted from the Allies’ concurrent deployment of a series of new countermeasures and technologies that reached maturity almost simultaneously: centrimetric radar aboard both ships and aircraft, efficient shipborne high-frequency direction finding, ahead-throwing weapons that permitted ships to fire antisubmarine bombs forward and thus retain sonar contact, very-long-range shore-based antisubmarine aircraft, escort carriers and escort support groups, and advances in decryption of German communications codes. The U-boat arm attempted to defeat these countermeasures by deploying its own new weaponry, the most important elements of which were radar warning receivers, heavy antiaircraft batteries, and acoustic torpedoes designed to hunt antisubmarines vessels. Not only did these fail to stem the tide of Allied success against the U-boats, but new convoy communications codes also defeated German cryptographers, rendering locating targets much more difficult. Then, in 1944, Allied military successes in France began to force German U-boats to make more extended passages to their patrol areas as their home ports moved farther from the Atlantic; German air bases also ceased to give aircraft quick access to British coastal waters.

During the final year of this conflict, U-boats equipped with snorkels entered service. The production of new, fast elektroboote (the radical new Type XXI submarines with high underwater speed) allowed the first examples to become operational, but their numbers were far too few to make any difference. Also, there were insufficient experienced crews available to exploit their potential and they had design and manufacturing faults. Such was the success of Allied antisubmarine measures during this period that full-scale convoying became unnecessary in some areas, and much of the focus of their escorts turned to hunting U-boats rather than directly protecting merchant shipping. The full measure of the defeat of the U-boats is indicated by the fact that more than two-thirds of the 650 German submarines lost during World War II were sunk in the last two years of the war.