THE BATTLE

Of the momentous events of the following day we have only two accounts and they are so short that they may be quoted in full.

From the ‘Anglo-Saxon Chronicle’: ‘He proceeded to Ethandun, and there fought with all the army and put them to flight, riding after them as far as the fortress, where he remained a fortnight. Then the army gave him hostages with many vows that they would go out of his kingdom.’

From ‘Annals of the reign of Alfred the Great’, by Bishop Asser: ‘The next morning he removed to Ethandun, and there fought long and fiercely in close order against all the armies of the pagans, whom with the divine help he defeated with great slaughter, and pursued them flying to their fortification. Immediately he slew all the men and carried off all the booty that he could find without the fortress which he immediately laid siege to with all his army. And when he had been there fourteen days the pagans, driven by cold, famine, fear, and last of all by despair, asked for peace.…’

It must be confessed that Asscr’s account reads like a mere embellishment of the Chronicle, and it is odd that Alfred had not given him some first-hand details of the battle, as he did in the case of Ashdown. In effect all Asser adds to our knowledge is the fact that the English fought in close order (densa testudine), a fact that is curiously omitted in Giles’s standard translation, and misquoted in Lee’s Alfred the Great.

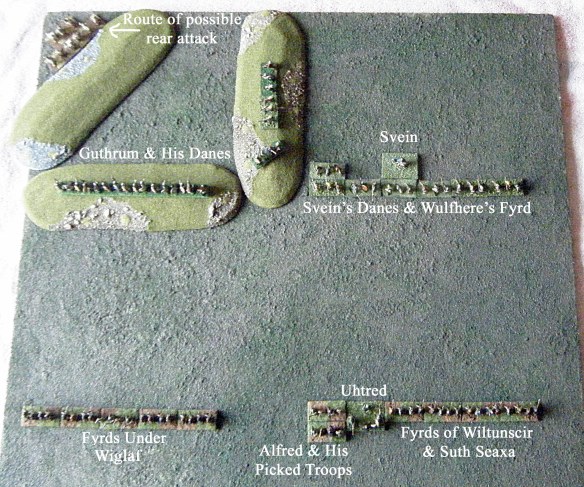

The whole battle is therefore a matter of pure conjecture. My own picture of the course of events is as follows:

When dawn appeared on the morning of the battle, the Saxon scouts on Battlesbury Hill who had previously reported the approach of the Danish army, spotted and reported to Alfred their precise dispositions, lining the ridge in front of them. Alfred came up to the hill, examined the position and decided on his method of attack. There was no obvious way of outflanking the position, even if such a manoeuvre ever entered the head of the impulsive king who only seven years before at Ashdown had charged ‘like a wild boar’ straight in the face of the enemy. One may assume that he employed the same tactics, charging in close order in an endeavour to pierce a hole in the enemy’s long line. The attack, whatever the tactics employed, was successful; the Danes fled towards their own base camp, even as they had fled seven years before. Those on the western end of the line presumably took the track leading over Bratton Camp, and those on the east the track leading past Edington. The former may be supposed to have attempted a stand on the top of the ridge 500 yards south of Bratton Castle (marked BB on the sketch-map). It forms a strong position. The Edington fugitives might try to hold the defile between Edington and Tinhead Hills. This position (marked CC) resembles the position of the field of Wodnesbeorh, in the two battles of A.D. 592 and 715. The third phase of the battle would be the pursuit to Chippenham, a further 14 miles to the north. A possible argument in favour of some of the fighting at least taking place on site BB is the proximity of the Bratton White Horse, believed by many to have been cut, in its original form, in celebration of the victory. In favour of site CC is the proximity to Edington, from which the battle drew its name. But this argument is not as strong as it may appear to modern eyes, for place-names in that area must have been few and far apart. Witness, the name Hastings for the battle fought on the Sanlake brook.

The fall of Chippenham crowned the victory of Edington and paved the way for the Christianization of the Danes and the extirpation of paganism in the land of England.

A NOTE ON THE RIVAL SITES

Considering the importance of the battle of Ethandun it is not surprising that numerous attempts to identify the site have been made through the ages. Camden was the first writer to equate Ethandun with Edington in Wiltshire. His view held the field for some centuries. Heddington in Wiltshire, Edington in Berkshire, Yattendon, Yatton, and Edington in Somerset have also been suggested, but all have been dropped except the last-named which still receives some support in Somerset. The claim for this Somerset site was first advanced by Dr. Clifford in 1877. It was repeated by the Rev. C. W. Whisder in 1906, but there are weighty objections to it. In the first place it cannot be supported on philological grounds: for it derives from Edwinetune (Edwin’s town), whereas the Wiltshire Edington has consistently appeared as Edendone, the Norman equivalent of Ethandun. In the second place, it does not fit in with the situation of Iglea, over thirty miles away. In the third place, it is contrary to Inherent Military Probability that Alfred would have selected as his point of concentration a place on the extreme left of his long line, necessitating a flank march of 100 miles on the part of the Hampshire contingent. None of these objections apply to the Wiltshire Edington. It is moreover supported by the two most recent historians of the period, Hodgkin and Stenton.

A NOTE ON EGBERT’S STONE

It is obviously of primary importance to ascertain the correct site of this stone, for the whole strategy of the campaign depends upon it. The Chronicle states that it was ‘on the eastern side of Seiwood’; Asser states that it was ‘in the eastern part of the wood which is called Selwood’. The modern village of Penselwood is about 7 miles west of Willoughby Hedge, but the extent of the wood in the ninth century is unknown. The O.S. Map of the Dark Ages shows it as being of considerable extent. Dr. G. B. Grundy, in the Archaeological Journal of 1918, placed the Stone at Willoughby Hedge and his view seems to have been accepted by the most recent historians of the period.

Before going further we must briefly consider two other neighbouring sites that have advocates. The first is Brixton Deverill, 3 miles due north of Willoughby Hedge. It lies in a valley, and seems an odd place for King Egbert to erect his Stone, for it could not be visible from any distance, nor is it on a junction of highways. The second is about one mile to the north-east of Westbury. This seems still more unlikely, for a march from this place to Iglea would involve turning sharp back for about five miles and then advancing along almost the same line—a nonsensical proceeding. Moreover the Westbury site is north, rather than east of Selwood.

Returning to the examination of Willoughby Hedge, Dr. Grundy confined his argument almost exclusively to the system of ancient trackways, a subject on which he was an unrivalled authority. He showed that tracks converged on Willoughby Hedge from all directions, making it a natural rendezvous for contingents coming from widely separated districts. To particularize, a track runs west by Kingsettle Hill (whereon is situated Alfred’s Tower). This is the track by which the Somerset contingent would travel and would lead to Cornwall. A second track runs almost due north to Iglea. This would be used in Egbert’s time by his North Wiltshire troops. A third goes north-east to Andover and North Hampshire. A fourth runs due east to Old Sarum and South Hampshire and a fifth goes due south to Shaftesbury and Dorset. The spot is 717 feet in height.

We have now to consider why King Egbert should elect to place a stone there. We may safely assume that it would be erected to mark or celebrate some outstanding event, such as a great victory or treaty.

Now in A.D. 815 and again in 825 Egbert conducted victorious campaigns against the men of Cornwall. It is probable that he would return from these campaigns along the ancient ridgeway, coming from the Mendip Hills. At the point where the trackways diverge near Willoughby Hedge, the South Hampshire contingent would take the right-hand fork heading for Southampton; those for North Hampshire the central track, whilst those for North Wiltshire would strike due north. At this spot therefore the victorious army would disperse. There would be leave-takings and perhaps the King would show his gratitude by giving a banquet. Is it too fanciful to picture that during the feasting some chieftain might make the suggestion that the spot would be a good place to erect a memorial-stone to record the victory? Willoughby Hedge was the highest point they had encountered since entering Wiltshire; it is a commanding site, and a stone erected here would be visible for many miles around in every direction. Here, then, I think is the most likely place we could find for the erection by Egbert of his memorial stone. Its site would become well known throughout Wessex, and Alfred in notifying the rendezvous would merely have to name the stone without any further specification. Nor, in referring to it afterwards did the chronicler or Asser think it necessary to define its position. Everyone knew where it was.

Alfred H. Burne