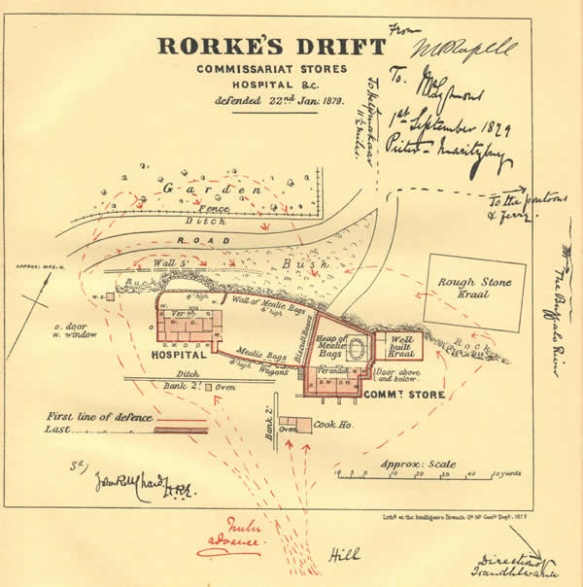

Lieutenant Chard’s famous drawing of the Rorke’s Drift battle, showing the main thrusts of the Zulu attack.

The Battle of Rorke’s Drift fully deserves its elevated status in the annals of British military history, if only as one of the most heroically fought and efficiently conducted small-scale military actions of the last 100-odd years. The British were, from the outset vastly outnumbered by up to thirty to one by their Zulu protagonists. In the context of the relatively confined space of the garrison, and the considerable opportunities for enemy concealment in the shrubs, bushes and caves outside and overlooking the garrison, British technical superiority had been much more limited than some observers have suggested. After the initial, albeit destructive volleys fired against the first wave of Zulu attackers, much (if not the majority) of the fighting was at close quarters. The survival of the garrison depended at its most critical times as much on rifle butts and bayonets as it did on the efficacy of the Martini-Henry Box .45 cartridge. The successful withdrawal from the hospital, for instance, was conducted largely at bayonet and assegai point. Indeed, the incredible closeness and intensity of the fighting was graphically testified to by Lieutenant Chard himself during his post-war extended audience with Queen Victoria in October 1879: ‘the fight was at such close quarters that the Zulus actually took the bayonets out of the rifles.’ (RA QVJ, 12 Oct. 1879)

It is now possible to evaluate command and control, and the overall conduct of the battle, more precisely in terms of both modern British military doctrine and the views of contemporary experts, notably Major William Penn Symons. A broad comparison of the events of the Rorke’s Drift battle with current key principles of war, namely selection and maintenance of aim; maintenance of morale; offensive action; surprise and concentration of force; economy of effort and security; flexibility; cooperation; and overall sustainability, is instructive.

Selection and Maintenance of Aim

In terms of selection and maintenance of aim, after the initial debate of whether to evacuate the garrison to Helpmekaar, Chard, Bromhead and Dalton collectively clearly defined and selected their defensive aims with commendable speed, only minutes after hearing the news of the Isandlwana disaster and the approach of the Zulu Undi Corps. In such a short time, the arrangement of the defences was a masterpiece with full use made of artificial and natural features. The stone and mud walls of the kraal, hospital and storehouse were fully utilised with a formidable mealie bag barricade along the perimeter, and the front perimeter was also given excellent elevation by its construction along the 3–4ft rocky ledge. These defensive aims were thus attainable and precisely prepared with a number of subsidiary aims, notably a secondary line of defence or fall-back position constructed of biscuit boxes. The broad strategic aim was, moreover, sustained throughout the battle, its defensive principles widely disseminated throughout the garrison, and made the main focus of activity for all the able-bodied men who were fully briefed on their tasks at their designated posts along the barricades.

Maintenance of Morale

The principle of maintaining morale was also clearly fulfilled, bearing in mind the terrible and unique battle conditions, in which so few British soldiers faced a ferocious enemy who had not only just annihilated a force twelve times their size, but also who patently gave no quarter. In terms of morale, Acting Assistant Commissary Dalton, by his experience, exceptional energy and raw courage, proved to be perhaps the most inspiring figure for the rest of the garrison. Thus Hook admiringly wrote: ‘He had formally been a Sergeant-Major in a Line Regiment and was one of the bravest men who ever lived’, a man who was seen at the start of the battle literally taunting the Zulus and beckoning them to come on. (Holme, Silver Wreath, Hook Account, p.63)

Bromhead’s clear popularity and extremely close rapport with his own B Company soldiers also played a key role in the resilience and survivability of the garrison – he constantly patrolled the perimeter, reinforcing weak points and always giving stirring encouragement to his men. For instance, Bromhead had given sympathy and even loaned his revolver to the seriously wounded Private Hitch, their bond of comradeship continuing well after the battle, as Bromhead ‘brought his Lordship to see me and was my principal visitor and nurse while I was at the Drift’. (Holme, Silver Wreath, Hitch Account, p.62)

Lieutenant Chard also attracted universal admiration from officers and men for his coolness under fire and the competence of his defensive preparations. Of the officers, Dalton, however, clearly occupied a special place in the hearts of the men of B Company. Major General Molyneux, thus recorded a moving incident which occurred at the end of the war:

After the war, the company of the 24th that had defended Rorke’s Drift was marching into Maritzburg amidst a perfect ovation. Among those cheering them was Mr Dalton, who, as a conductor, had been severely wounded there; ‘Why, there’s Mr Dalton cheering us! We ought to be cheering him; he was the best man there’ said the men, who forthwith fetched him out of the crowd and made him march with them. No-one knew better the value of this spontaneous act than that old soldier. The men are not supposed to know anything strategy, and not much about tactics, except fire low, fire slow, and obey orders; but they do know when a man has got his heart in the right place, and, if they had a chance they will show him that they know it. Mr Dalton must have felt a proud man that day.

Molyneaux, Campaigning in South Africa, pp.206–7

The outstanding performance of the officers instilled a high degree of determination, confidence and defensive spirit, evident throughout the battle.

Offensive Action

In terms of the principle of offensive action, both Chard and Bromhead managed the battle exceptionally well and instinctively understood that ‘a sustained defence, unless followed by offensive action will only avert defeat temporarily’. Thus Bromhead organised mobile bayonet parties, a crude human form of ‘mobile weapons platforms’, which were constantly deployed to repel Zulu breakthroughs and thereby effectively depriving them of initiative. ‘Fire mobility’ was thus fully sustained throughout the siege.

Surprise and Concentration of Force

Surprise was also a principle which was well exploited by all the officers commanding the garrison of Rorke’s Drift. The frequent change of tactics, from sustained volley fire at the start of the siege and the potent use of enfilading fire from the storehouse throughout the siege, followed by the sudden retreat from the hospital perimeter to the well-prepared biscuit box barricades, continually wrong-footed the attacking Zulu force. Allied to this tactic was the extensive use of ‘concentration of force’ at decisive times and places which accompanied these deceptions. Hence Chard’s and Bromhead’s constant switching of their soldiers from the front and rear barricades in the first two hours of the siege confused and distracted the Zulu attackers in their constant search for weak points along the perimeter.

Economy of Effort and Security

Economy of effort – the efficient, at times frugal, use of resources – was also applied extremely well. Lieutenant Bromhead was the pivotal man in terms of the distribution of the ammunition supply. Constantly urging his men of the need to conserve rounds during the later stages of the siege, both he and Chard kept meticulous accounts of the allocation and quantity of ammunition. In this way ‘overall security’ was achieved, with Chard always guarding an adequate reserve. The judicious allocation of troops and resources was therefore at a premium in the Rorke’s Drift siege. In summary, in regard to the three interrelated principles of concentration of force, economy of effort and security, Lieutenants Chard, Bromhead and Acting Assistant Commissary Officer Dalton achieved a high level of excellence.

Flexibility

Flexibility was also ably demonstrated by the commander, Lieutenant Chard. Without undermining his overall defensive aim, Chard brilliantly modified his plan to rescue the much more dangerous and precarious situation occurring after the retreat from the hospital. In this new tactic, part of the garrison’s effort was redeployed, using the lulls in the fight after midnight to construct a last bastion of defence – the mealie bag redoubt. This manoeuvre demonstrated both elasticity of mind and resourcefulness at this critical last stage of the battle. It was a simple, but highly effective solution, designed to both protect the wounded and provide a final elevated concentration of fire for up to forty soldiers.

Cooperation

Cooperation or teamwork was also ably demonstrated by all members of the garrison. All four ‘services’ or units present at the siege, the Commissariat, the Army regulars, the Chaplain and even the Army Hospital Corps, each massively supported each other and adapted to each other’s requirements; key ‘players’ such as Byrne, Reynolds, Dalton, Dunne, Chaplain Smith, Bromhead and Chard all worked closely together to carry out essential duties ranging from close-quarter fighting at the barricades to the distribution of food and ammunition. Surgeon Reynolds was, perhaps, the most outstanding example, both attending to the wounded and supplying the hospital under fire with much-needed ammunition. His VC citation highlighted this achievement.

Overall Sustainability

Overall sustainability was definitely achieved. Chard and Bromhead kept an exceptionally fine balance between ‘teeth and tail’, wholly maintaining both the physical and psychological condition of the soldiers in order to maintain morale. It was an important achievement, bearing in mind the inexperience and youth of a good many of the garrisons’ 2/24th regulars.