The heroic defense of Rorke’s Drift during the Zulu War (1879) took place only hours after the disastrous and bloody Battle of Isandlwana (22 January 1879). This action represented the epitome of bravery and endurance of the British soldier. There were only two pass able tracks from Nat al into Zululand, and one of them crossed the Buffalo River at Rorke’s Drift. This track continued to run eastward via Isandlwana to Ulundi.

There were two buildings about one – half mile from Rorke’s Drift that had originally been Jim Rorke’s farm, with high ground to the south. These buildings had been requisitioned by the British and were being used as a base hospital and supply depot for the center column (No. 3) of the invasion force.

Lieutenant (later Colonel) John R. M. Chard, who had arrived at Rorke’s Drift on 19 January 1879, was in command of the post. He was assisted by Lieutenant (later Maj or) Gonville Bromhead, commander of Company B, 2nd Battalion, 24th Foot, which had been designated to protect the bas e. The garrison at Rorke’s Drift consisted of about 8 officers and 131 other ranks, including 35 sick in hospital.

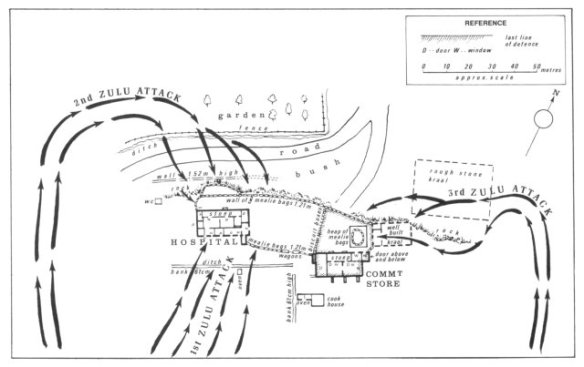

In the early afternoon of 22 January 1879, firing was heard at Isandlwana, 6 miles directly to the east of Rorke’s Drift. Horsemen fleeing from Isandlwana stopped long enough to shout that the British force there had been overrun and massacred. Chard directed that immediate measures be taken to fortify the post, and 200-pound mealie (corn) bags and large biscuit boxes were used to construct walls and redoubts. Firing loopholes were hastily smashed in the hospital, and one solder later observed that “we were pinned like rats in a hole ” (Smythe n. d., p. 2). A basic perimeter was constructed in about an hour.

At about 5:00 P. M., a soldier spotted the Zulus approaching and shouted, “Here they come! Black as hell and thick as grass!” (Glover 1975, p. 98). The 4,000 Zulus were members of three regiments that had been in reserve in Isandlwana and had seen only limited action. They were eager to prove themselves as warriors. About 500 Zulus rushed to the south wall of the British post in their initial assault, but they were stopped by the British rifle fire. As more Zulus rushed to encircle the station, a general assault began.

About an hour later, Chard ordered the abandonment of the wall in front of the hospital. The men in the hospital were fighting the Zulus and withdrawing room by room when the thatched hospital roof was lit on fire, and they fell back on a new wall built in front of the storehouse. By 10:00 P. M., the British soldiers were within the wall protecting the storehouse. Relentless Zulu assaults continued until after midnight and then began to slacken as the attackers became exhausted. Sporadic assaults continued as the attackers had to struggle over the heaps of Zulu bodies to get close to the British. “All we saw was blood,” one Zulu warrior later recalled (Edgerton 1988, p. 105).

By 4:00 A. M., the area was silent and the attack was apparently over. The Zulus reappeared at about 7:00 A. M., but they only rested for a short time before moving to the east. About 400 dead Zulu littered the ground, and the British lost 17 killed and 10 seriously wounded. The defense of Rorke’s Drift was a triumph of British courage and skill over tremendous odds, but it was a relatively small victory. Eleven of the Rorke’s Drift defenders, including Chard and Bromhead, received the Victoria Cross, the largest number for a single engagement in British history. These awards were spread out over an extended period, to maintain public interest and support. The epic of Rorke’s Drift also helped restore British military prestige after the humiliating defeat at Isandlwana-and divert attention from it.

References: Barthorp (1980); Chadwick (1978); Edgerton (1988); Glover (1975); Knight (1990);Morris (1965); Smythe (n. d.)