In 1935 the German Air Ministry announced specifications for a new, twin-engine Schnellbomber (fast bomber). One year later Junkers beat out two other contenders with the Ju 88, a highly streamlined, smoothed-skinned airplane with mid-mounted wings. A crew of four sat under a large glazed canopy while a bombardier gondola, offset to the left, ran back from the nose. Test results were excellent, but Luftwaffe priorities were skewed to other craft, and production remained slow. By the time World War II erupted in September 1939, only about 50 Ju 88s had reached Luftwaffe units.

Test-Flying the Ju 88

During World War II, exhaustive tests were carried out on all airworthy Luftwaffe machines falling into British hands. Most major variants of the Ju 88 formed part of this collection, ranging from an A-1 acquired during 1940, and culminating with the G-1 example arriving in July 1944. Each was flown by future test pilots of post-war note who were already entering this career on either side of VE Day.

Ju 88A-5 Capt Eric ‘Winkle’ Brown first got his hands on a Ju 88A-5 variant during late 1943, this aircraft having inadvertently landed at Chivenor in 1941. Brown’s initial impression upon entering was that a crew of four would make for extremely cramped personal conditions. More noteworthy, given his small stature, was the very generous fore-and-aft seat adjustment. This was a positive factor compared to most Allied military aircraft, where in Brown’s view the seat-to-pedal arrangement proved to be almost totally in favour of large pilots! One limitation relating to the otherwise sound controls layout involved the engine throttles. These were placed too far back and too low, requiring the pilot to change his hand action from a pull to a push position – not the best of arrangements during what was a critical phase of any flight!

Engine start-up of the Jumo 211 G-1s could be achieved internally using the electrically energized inertia starters, or through use of a starter trolley, the latter sparing the draining of the Ju 88’s batteries. Taxiing was easy thanks to quick responding brakes and an unlocked tail-wheel; it was locked prior to take-off, otherwise operation of the hydraulic system was impeded. In addition the oil and coolant radiators had to be fully opened during this stage of the sortie.

For take-off the flaps were set one-third open, and the radiator gills closed to a similar degree. Rudder and aileron trim-tabs were set at ‘zero’, and elevator trim-tabs set for a marginal nose-heavy configuration. On opening up power Brown’s experience was that differential throttle movements could easily induce a swing if power was applied too rapidly. Also, considerable forward pressure had to be applied to the control column in order to lift the tail up and gain full rudder response in so doing.

Once in flight, both rudder and ailerons proved very responsive throughout the entire range of speed applied to the Ju 88. The automatic tail incidence control was of material assistance when noticeable elevator movements were called for; this system was linked to the dive-brakes in a manner that placed the elevators in the ‘dive’ mode and returned them to ‘level’ when the dive-brakes were opened and shut. Two incidental advantages of the system lay in the fact that the pilot could avoid having to ensure the propellers did not over-speed during the dive, and did not have to rely upon muscle power to regain level flight!

A practice ‘landing’ with flaps and undercarriage lowered established the stalling speed to be just over 145kmph (90mph), the indication coming in the form of a sharp wing-drop. The resultant approach saw Brown put the wheels down at around 225kmph (140mph), and moving the flaps to an interim position. Full flap was applied with the speed reduced to 190kmph (120mph), and a pronounced nose-up sensation was swiftly countered by the automatic tail-incidence mechanism. Touchdown was at 180kmph (110mph), with the throttles having to be instantly retarded as the airfield boundary was crossed. Premature lowering of the tail was not recommended, since rudder ‘block-out’ could then contribute to any swing that might develop before the aircraft had lost speed. (Brown also commented on the emergency procedure for lowering the undercarriage should the engine-activated hydraulic-pump system go ‘out’. This entailed three minutes of feverish hand-pumping that only affected the main wheels, so leading to a very pronounced nose-up touch-down and landing run, not to say a severe damage effect upon the rear fuselage in the process!)

Ju 88G-1 Wg Cdr Roland Beaumont was attached to the Central Fighter Establishment’s tactics branch at Tangmere following his return from captivity. On 14 July, having read up his notes on the Ju 88G-1, he climbed up rather apprehensively into the cockpit. His initial impression was of restricted vision thanks to the canopy framing. On the other hand, the controls and instrument layout largely met with his approval excepting the fuel system, which he regarded as complex. Engine start, produced a pleasant noise level, but this turned to a harsher note as power was applied. Movement of the controls displayed smooth and immediate response, but Beaumont felt that the nose-up attitude while taxiing made him feel uncomfortable. Once airborne, however, he quickly adapted to handling what was one of his first multi-engine experiences, most of his flying having hitherto been in single-engine fighters.

The take-off had proved surprisingly easy. Power had been gently applied to counteract any tendency to swing, but the machine lifted off before reaching 100 per cent effort, and required no further elevator action other than that previously applied to lift the tail up. Once the undercarriage was raised, the subsequent climb-rate applied was comparable to its RAF contemporary the Mosquito. Control response was very good, while, after levelling out and holding a speed around 370kmph (230mph), minimal rudder and elevator trimming was required.

Beaumont then put the Ju 88 through a series of manoeuvres ranging from partial rolls and tight turns and dives, to climbs and wingovers. None of these actions raised any material control problems, but the dives reaching 300 IAS did produce an enhanced and distracting noise-level.

As Tangmere was looming up a Mosquito was seen, which Beaumont dived upon. However the pilot evaded with a tight turn and a steep circling duel ensued. The Ju 88 not only held position, but also initially began to close the circle. However, the descending nature of the ‘dog-fight’ impelled Beaumont to ease off, after which the situation was swiftly reversed. (Given his unfamiliarity with the Ju 88 he had done very well, especially since his opponent was none other than a doyen of twin-engine and Mosquito flight-control. Sqn Ldr Bob Braham!)

The landing approach was made marginally faster than the pilot’s notes indicated until over the runway threshold, and the touch-down proved as smooth and uneventful to Beaumont as any other aspect of the flight.

#

In combat the Junkers design was fast, carried a good bomb load, and could absorb great amounts of damage. Moreover, although originally intended as a bomber, it could be adapted to virtually every mission assigned to it: mine-laying, night-time fighting, reconnaissance, anti-ship patrols, heavy fighter, ground attack, and dive-bombing. Ju 88s accordingly distinguished themselves in combat from England to Russia, Norway to North Africa.

The prototype Ju 88 flew on 21 December 1936 with two 1,000-hp (746-kW) Daimler-Benz DB 600Ae inline engines with annular radiators, giving them the appearance of radials; the use of these radiators was to continue throughout the development of the aircraft. Further prototypes followed, the third having 1000-hp (746-kW) Junkers Jumo engines and this, during evaluation, reached 323 mph (520 km/h). The high performance of the Ju 88 encouraged record-breaking flights, and in March 1939 the fifth prototype set a 1,000-km (621-mile) closed-circuit record of 321.25 mph (517 km/h) carrying a 4,409-lb (2000-kg) payload. A total of 10 prototypes were completed and the first of the pre-production batch of Ju 88A-D bombers flew in early 1939. Production aircraft were designated Ju 88A-1 and began to enter service in September 1939.

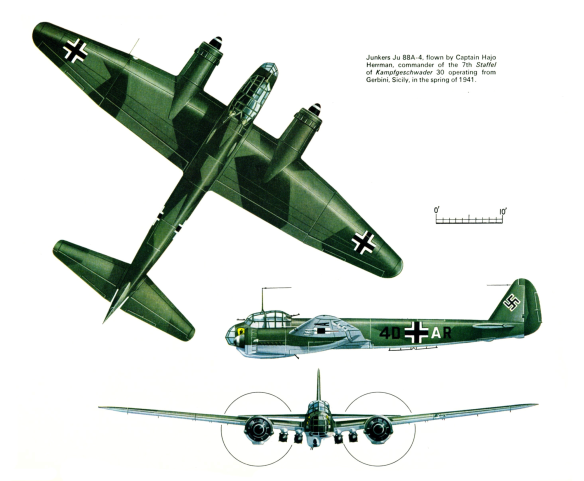

Early teething troubles were gradually ironed out and sub-variants began to appear, including the Ju 88A-2 with jettisonable rocket packs for assisting takeoff in overload conditions, the Ju 88A-3 dual-control trainer and the Ju 88A-4, the first considerably modified development. Designed around the new and more powerful Jumo 211J engine, the Ju 88A-4 had increased span and was strengthened to take greater loads.

Because of problems with the new engine the Ju 88A-4 was overtaken by the Ju 88A-5, which featured the new wing but retained the former engines. During the Battle of Britain many Ju 88A-5s were fitted with balloon-cable fenders and cutters to combat the UK’s balloon barrage, and in this form they became Ju 88A-B aircraft. Some Ju 88A-5s, converted to dual-control trainers, were designated Ju 88A-7.

By the time definitive Ju 88A-4s began to enter service, lessons learned in the Battle of Britain had dictated heavier armament and better protection for the crew. Several different armament layouts were used, but a typical installation was a single 7.92-mm (0.31-in) MG 81 machine-gun on the right side of the nose and operated by the pilot, and two 7.92-mm (0.31in) MG 81s or one 13-mm (0.51-in) MG 131 machine-gun firing forward through the transparent nose panels, operated by the bomb aimer. The same option was available in the ventral gondola beneath the nose, firing aft, while two other MG 81s were in the rear of the cockpit canopy. Some 4,409 lb (2000 kg) of the bombload was carried beneath the wings, both inboard and outboard of the engines, while the internal bomb bay held another 1,102 lb (500 kg).

Sub-variants of the basic Ju 88A extended up to the Ju 88A-17; space considerations preclude detailed mention of all these, but the Ju 88A-12 and Ju 88A-16 were trainers; the Ju 88A-8 and Ju 88A-14 had cable cutters; the Ju 88A-11 was a tropical variant; and the Ju 88A-17 was the Ju 88A-4 adapted to carry two 1,686lb (765-kg) torpedoes. The Ju 88A-15 with enlarged bomb bay could carry 6,614 lb (3000 kg) of bombs. By the end of 1942 the Luftwaffe had taken delivery of more than 8,000 Ju 88’s. While the Ju 88A was in quantity production, Junkers was developing the Ju 88B, the prototype of which flew in 1940 with two 1,600-hp (1193-kW) BMW 80lMA radial engines. Main change in appearance was to the forward fuselage, which was enlarged and extensively glazed, and there was a marginal increase in performance over the Ju 88A, though this was not sufficient to warrant a change in the production lines, and only 10 pre-production aircraft were built.

For the Battle of France, the Ju 88 equipped one three Grüppe Geschwader, and four Grüppen within other Geschwaders. By Adlertag, the Luftwaffe included 13 Grüppen of Ju 88s, and these were able to play a decisive part in the Battle of Britain, highlights including a mass raid on Portsmouth by 63 Ju 88s on 12 August. The Ju 88 was far and away the best of the Luftwaffe bombers operating during the Battle of Britain, and suffered a correspondingly lower attrition rate than either the He 111 and Do 17. The aircraft was vulnerable to single seat fighters, of course, but there were numerous instances documented where Ju 88s were able to escape from an attack by diving away from their pursuers at very high speed.

The original Ju 88A-1 which formed the backbone of the Kampfgeschwaderen during the Battle of Britain were prone to a number of problems, some relatively minor, others much more serious. These led to the imposition of a number of fairly restrictive limitations on speed and manoeuvring. These limitations were not applied to the later Ju 88A-4, though problems with this version’s 1350 hp Jumo 211J engines meant that it did not reach the frontline until after the Battle, and nor did its specialist reconnaissance equivalent, the Ju 88D-1. Fortunately, an interim ‘improved Ju 88’ was available to the Luftwaffe in time for Adlertag. This was the Ju 88A-5 (with the Ju 88D-2 as the recce equivalent), which featured a longer-span, strengthened wing with inset metal-skinned ailerons, and a much-increased bombload. For the first time, the Luftwaffe had a Ju 88 not choked by artificial limitations, and the Ju 88A-5 performed with great distinction. The final variant to participate in the Battle was the initial reconnaissance Ju 88D-0, a handful of which flew from Norway.

It was inevitable that the Ju 88’s basic design would also be adapted to the fighter role, although initially the need for bombers dictated a low priority for fighter versions. However, the second preproduction Ju 88A was adapted in mid-1939 to have a solid nose with three 7.92-mm (0.31-in) MG 17 machineguns and one 20-mm FF/M cannon firing forward. Single 7.92-mm (0.31-in) MG 15 machine-guns were mounted in dorsal and ventral positions firing aft.

The fighter version would have become the Ju 88C- 1, with an additional forward-firing20-mm cannon, but plans to use 1,600-hp (1193-kW) BMW 801 engines had to be dropped since these were required for the Focke-Wulf Fw 190. However, many Ju 88A-1s were converted on the production line as Ju 88C-2 fighters. Around 130 were built, and these operated as night-fighters in 1940-1; they also carried out night intruder patrols over British bomber bases.

The first Ju 88 fighter to be built from scratch was the Ju 88C-4, which had the longer span wing of the Ju 88A-4 and 1,340-hp (999-kW) Jumo 211J engines. Attempts to provide more power by the use of 1,700-hp (1268-kW) BMW 801D radial engines produced the Ju 88C-3, of which only one was built, and the Ju 88C-5; a pre-production batch of 10 was built before the lack of BMW engines again killed the idea.

The Ju 88C-6 which followed after less than 100 Ju 88C-4s was basically a more heavily armoured day fighter and went into large-scale production; it was a sub-variant of this type, the Ju 88C-6b, which became the first radar-equipped Ju 88 night-fighter, with nose mounted Lichtenstein radar. It was to turn the tide appreciably against the RAF bombers, for on five operations between 21 January and 30 March 1944 342 bombers were destroyed out of 3,759 dispatched.

Alphabetically out of sequence was the Ju 88R-1, which had the same airframe and armament as the Ju 88C-6b but used BMW 801MA radial engines, the supply position on these having eased. The Ju 88R-2 was similar, but with BMW 801D engines.

Long-range reconnaissance versions of the Ju 88 were developed as Ju 88D aircraft; they were based on the Ju 88A-4, and almost 1,500 were built between 1941 and 1944 to see action on all fronts. The variants from Ju 88D-1 to Ju 88D-5 differed in engine and detail.

In an effort to improve stability of the Ju 88 a new, tall, square-cut fin and rudder was fitted to a Ju 88R-2, the new variant becoming, in its production form, the Ju 88G-1. The twin nose cannon were removed, but the aircraft carried Lichtenstein nose radar, with Flensburg aerials on the wings that enabled it to home in on RAF bombers using tail-warning radar emission.

The Ju 88G-1 had BMW 801D engines and developed into a number of sub-types; the Ju 88G-4 was the first to use the Me 110’s schräge Musik installation of two MG 151 cannon which fired forwards and upwards. Main differences among the various sub-types were in the types of radar and armament fitted, although the later variants from Ju 88G-6c reverted to Jumo engines. The last production model of the series was the Ju 88G-7c.

Development of the basic Ju 88D reconnaissance aircraft resulted in the Ju 88H series, the prototype of which combined the wings and BMW engines of a Ju 88G-1 with the fuselage and tail of a Ju 88D-1. ‘Plugs’ were inserted in the fuselage fore and aft of the wing, increasing its length by 10 ft 8 in (3.25 m) to 57 ft 10 1/2 in (17.65 m). With the additional fuel tanks that could now be carried the Ju 88H had a range of 3,200 miles (5150 km).

Ten Ju 88H-1 reconnaissance aircraft and 10 Ju 88H- 2 long-range fighters were built, the latter with six forward-firing 20-mm MG 151 cannon in place of the Ju 88H-1’s cameras and radar. Despite being built in such small numbers, these types saw action over the Atlantic.

As Ju 87s were converted for tank-busting missions, so were a number of Ju 88s as the Ju 88P series. In 1942 a Ju 88A-4 airframe became the prototype, and was tested with a 75-mm (2.95-in) KwK 39 cannon mounted in a larger underbelly fairing. A small batch was ordered as the Ju 88P-1 with 75-mm (2.95-in) PaK 40 cannon, a 7.92-mm (0.31-in) MG 81 forward-firing machine-gun being used by the pilot for aiming the cannon. The usual ventral and dorsal rear-firing machine guns were carried for defence. Other sub-variants with different forward-firing cannon were the Ju 88P-2 and Ju 88P-3 (two 37-mm BK cannon) and the Ju 88P-4 (one 50-mm BK5 cannon). Thirty-two of this final variant were delivered.

Performance of the Ju 88 bombers by 1942 was such that they were becoming progressively unable to escape from enemy fighters, and in order to improve their chances the Ju 888 series was developed. Two BMW 801D 1,700-hp (1268-kW) radial engines were married to the Ju 88A-4 airframe for the prototype Ju 88S, which reached a speed of 332 mph (535 km/h). A pre-production series was ordered, followed in 1943 by production Ju 88S-1 aircraft with BMW 801G-2 engines which, with power boosting, gave 1,730-hp (1290- kW) at 5,005 ft (1525 m). To save weight, armament was reduced to a single rear-firing 13-mm (0.51-in) MG 131 machine-gun and a maximum speed (with nitrous oxide injection) of 379 mph (610 km/h) was reached at 26,245 ft (8000 m). Two more sub-variants were built, the Ju 88S-2 and Ju 88S-3, the latter having Jumo 213A engines which, with injection, gave 2,125 hp (1585 kW) and a speed of 382 mph (615 km/h) at 27,885 ft (8500 m). Only a few Ju 88S aircraft were built, with production beginning in 1944, and a high-speed photo-reconnaissance version, the Ju 88T, was also built in small numbers. Total Ju 88 production reached almost 15,000 in nine years.

Specification

Junkers Ju 88A-4

Type: four-seat bomber/dive-bomber

Powerplant: two 1,350-hp (1007-kW) Junkers Jumo 211J-112-cylinder inverted-Vee piston engines

Performance: maximum speed 292 mph (470 km/h) at 17,390 ft (5300 m); maximum cruising speed 248 mph (400 km/h) at 16,405 ft (5000 m); service ceiling 26,900 ft (8200 m); maximum range 1,696 miles (2730 km)

Weights: empty equipped 21,737lb (9860 kg); maximum take-off 30,865 lb (14000 kg)

Dimensions: span 65 ft 7 1/2in (20.00 m); length 47 ft 2 3/4 in (14.40 m); height 15 ft 11 in (4.85 m); wing area 586.6 sq ft (54.50m2)

Armament: one forward-firing 7.92-mm (0.31-in) MG 81 machine-gun, plus one forward-firing 13-mm (0.51in) MG 131 or two 7.92-mm (0.31-in) MG 81 machine-guns, two similar guns in rear of cockpit firing aft and two firing aft below the fuselage, plus up to 4,409lb (2000 kg) of bombs carried internally and externally

Operators: Luftwaffe, Finland, France, Hungary, Italy, Romania