Peashooters

The Boeing P-26 became the standard single-seat pursuit plane in the mid-1930s. General Andrews, as previously mentioned, assigned these aircraft to the 1st and 20th Pursuit Groups when he became Commanding General, GHQ Air Force. The Air Corps had already announced competition for designing new planes. Seversky won a contract in May 1936 for 77 P-36. Shortly afterwards, the Air Corps ordered 3 P-36s from Curtiss for testing and the following year placed an order for 210 P-36As. The P-35 and P-36 were the first single-seat pursuit planes with enclosed cockpits and retractable landing gear available to Air Force units. They cost a lot more but performed much better than the P-26s.”

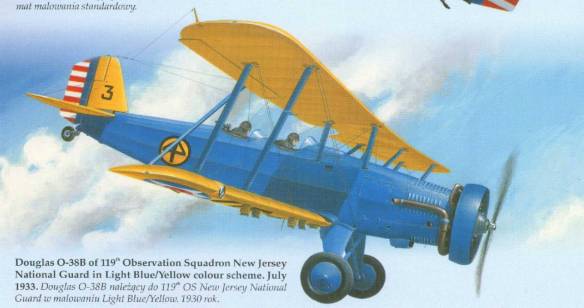

The 1st Pursuit Group got the P-35s, the first arriving at Selfridge Field, Michigan, at the end of December 1937. All three pursuit groups in the United States accepted P-36As after deliveries to Air Force units commenced in September 1938. When the first P-36 reached Barksdale Field, Louisiana, the 20th Group reported it soon would be “flying on silver wings instead of the old faithful blue and yellow.”79 Since adoption of chrome yellow for wings and tails in 1927, fuselage coloring had changed from olive drab to light blue. Besides, squadrons now used identifying coloring on their aircraft. Orange paint on a motor cowling at Selfridge Field, for instance, identified the plane as belonging to the 27th Pursuit Squadron; red indicated the 94th Pursuit Squadron. Upon receiving all-metal aircraft, the Air Corps continued to paint them yellow and blue until 1937.

The Peashooter was 23 feet 7 inches long, and its wing spanned 28 feet. The fighter weighed 2,271 pounds empty and just over 3,000 pounds loaded. It was armed with two synchronized machine guns in the floor of the cockpit, either two .30 calibers or one .30 and one .50 caliber. The plane also could carry up to 200 pounds of bombs in a rack under the fuselage. The Peashooter appeared at the height of the Depression, when the various branches of the military were competing for the limited funds available from the government. Many people still did not take military aviation seriously, and the Army Air Corps was anxious to show off its capabilities in the hope of gaining public support for expanding the service. As a result, the mid-1930s became arguably the most colorful period in American aviation history.

The standard finish applied to Army aircraft included chrome-yellow wings and tail and a blue fuselage. The rudder was painted with a blue vertical stripe on the leading edge and 13 horizontal alternating red and white stripes on the trailing edge. There were also colored stripes on the wings and fuselage, denoting the individual aircraft’s position in its flight, squadron and group. In addition, squadrons and groups added their own dazzling markings to their planes. Aircraft in many of the regular service squadrons during the 1930s were decorated more elaborately than any military aircraft since, with the possible exception of those operated by special aerobatic units. Particularly flamboyant were the P-26s flown by the 17th Pursuit Group at March Field in Southern California, which consisted of the 34th, 73rd and 95th Pursuit squadrons. The 34th Pursuit Squadron members were the original “Thunderbirds,” and their P-26s bore that famous insignia 13 years before the U.S. Air Force was created.

Only two P-26 Peashooters exist in collections today — one at the Smithsonian’s National Air & Space Museum and the other in the collection of the Planes of Fame Museum in Chino, California. The U.S. Air Force Museum in Dayton, Ohio, has a full-scale reproduction incorporating as many real P-26 components as possible. The P-26A on display is painted in the markings (c.1933-39) of the 19th Pursuit Squadron, 18th Pursuit Group, based at Wheeler Field, Hawaii. The Light Blue fuselage and Chrome Yellow wings were standard for the 1934-1938 time period, although Olive Drab was an accepted alternate color for the fuselage.

Blu and Yella

The use of two color schemes, Light Blue for trainers, and Olive Drab for tactical aircraft, caused logistical headaches for Air Corps maintenance facilities. Quantities of O.D. and Light Blue paints were required in stock at all time. Another problem was the need to know an aircraft’s ultimate destination before paint could be applied: examples of many aircraft served in the training roles, and thus could require blue fuselages.

The solution, as recommended by the Chief of the Material Division in January 1934, was to standardize one paint scheme for all aircraft, regardless of role. His choice was Light Blue fuselages and Yellow wings and tails, reasoning that high visibility was essential for trainers, while temporary water paint camouflages made the lower-contrast Olive Drab for tactical aircraft unnecessary. Stocks of Olive Drab were at the reorder point, making a timely decision that much more important, and in February the recommendation was approved by the Chief of the Air Corps. Revised specifications and T.O’s were printed in May, and shortly afterward, tactical aircraft were noted with Light Blue fuselages.

Overnight repainting of the entire inventory was not suggested, and certainly did not occur: the added burden on depots would have been far too expensive. Instead as aircraft went through periodic depot overhaul, old paint was to be replaced with a fresh coat of Light Blue. It took several years for the process to be completed.

Black and white photos give the impression that several hues of Light Blue were being applied by the Air Corps. Although several shades of Light Blue were used, they did not vary as much as photographs would indicate. Tonal shifts of contemporary films are the root of the confusion; the two standard films of the day either lightened (Orthochromatic) or darkened (Panchromatic) any blues photographed. Light Blue appears so dark on Panchromatic film that is often difficult to tell from Drab Olive.

Misinterpretation of black and white photos may have led to the contention that a light green paint was used by the Air Corps in the mid-‘30s. Certainly, records of this period do not support this, and those fuselages alleged to be light green were probably light blue.