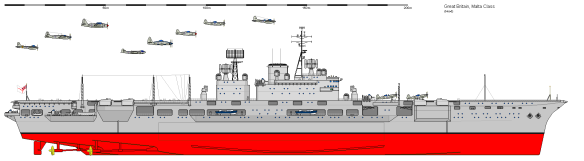

The final version of Malta’s flight deck design in 1945. The dotted lines show the dimensions of the single-deck hangar below it.

Malta’s open hangar design in 1945 compared with the USS Essex and the closed hangar in the Ark Royal that was under construction at the time.

The Malta Class marked a major change in British aircraft carrier design. Work on them started after the Joint Technical Committee recommended that future naval aircraft should be allowed to grow in both size and weight up to a maximum of 30,000lb to provide improved performance. The Future Building Committee had already considered the impact such aircraft would have on the design of the ships that would operate them, and ordered new designs. Previous British carriers had been designed around the assumption that the aircraft complement would be the maximum number of aircraft that could be stowed in the hangar, and that aircraft would be launched in small numbers over a long period. Experience by 1942 had shown that many more aircraft needed to embarked, and that they would often need to be launched in large numbers for strike operations. The Admiralty accepted at this time that embarked fighters represented a better air defence for the fleet than either guns or armour. The armoured double hangar limited the size of the flight deck, and the medium-range-gun mountings on their sponsons aft narrowed it still further, limiting the size of any deck park and the maximum number of aircraft that could be ranged for take-off at any one time. Despite the acceptance of a low maximum speed for the 1942 light fleet carriers, it was believed that fleet carriers must be able to accelerate rapidly to 30 knots in order to launch large, heavy aircraft, and that powerful machinery would be needed for them.

Technical background

Design studies began in February 1943 with consideration of a lengthened Ark Royal, but were soon expanded to consider ships with single or double hangars, up to 900ft long and 54,000 tons deep load. Hangars with open sides like the USN Essex Class were considered, but DNC recommended against them as closed hangar designs, even if the sides were not armoured, represented a more efficient and lighter hull. A ship’s hull can be considered as a hollow beam which is stressed by the distribution of buoyancy caused by wave motion. In closed-hangar ships the flight deck is the upper part of the beam; in open-hangar ships the flight deck is built as superstructure and the hangar deck becomes the upper part of a smaller beam. The deeper beam of the closed hangar represents the stronger and lighter structure; it is capable of resisting greater loadings, and the difference between the two can be considerable. Against this, the Admiralty was aware that the USN was able to run aircraft engines in its open-hangared ships and bring them rapidly to the flight deck to increase the size of a launch. It was also believed to be easier to move aircraft in the large, open hangars of American ships than in the relatively cramped closed hangars of existing British ships, but many other factors would have to be taken into consideration if an open-hangar design was to be considered seriously. Both four-and five-shaft layouts were considered and various applications of armour were investigated.

The initial Design A was considered too small and replaced by Designs B and C, which were put before the Admiralty Board on 17 July 1943. Design B featured a single closed hangar and C a double closed hangar at 55,000 tons deep load. It was to operate 108 aircraft in a fifty/fifty mixture of fighters and TBD requiring a ship’s company of at least 3,300. An open-hangar equivalent was sketched and submitted for comparison; it had an unarmoured flight deck but armour in the hull under the hangar deck. It was calculated at 61,060 tons at deep load. Design C, although not yet fully developed, was approved by the Board on 8 October 1943. Such was the importance placed on these ships by the Board that the order for a fourth unit of the Audacious Class was changed to a Malta on 12 July 1943, and three others were ordered on 15 July so that no time would be lost while the design was finalised. Design C was ready for Board approval by April 1944, but the Fifth Sea Lord, responsible for air matters, reopened the question of an open hangar design after urgent representations from aircrew with extensive operational experience. The matter was discussed again, and the Board decided at its meeting on 19 May 1944 that the operational advantages of an open hangar were sufficiently compelling for it to be substituted for design C. DNC objected that the change of policy would delay the ships’ construction by eight months and demonstrated how aircraft could be warmed up in the after part of the upper hangar to allow large launches from Design C, but the requirement for an open hangar stood.

A new Design X was prepared and submitted to the Board in August 1944. At 60,000 tons deep load it had a hangar that was open-sided aft but plated-in forward to prevent water ingress in rough weather. There was no flight deck armour, but it had 6in protection over the citadel under the hangar deck; there were two centreline and two side lifts. The latter were virtually impossible to fit in a closed-hangar design and had become appreciated by the Americans as one of the big advantages of the open design, as they allowed rapid aircraft movements while flying operations were in progress. As logistic resupply in the Pacific grew in importance it was also appreciated that the side lift allowed stores to be transferred rapidly into the hangar by jackstay transfer from a stores ship alongside and then distributed throughout the hull.

The design differed from all previous British carriers in that the flight deck would be built as superstructure and, therefore, needed to incorporate expansion joints. The island had grown to accommodate new radars under development and the air direction rooms and operations rooms to make use of them. By Design X it was split in two to allow an expansion joint approximately amidships. Advantage was taken of the gap to make both sections into aerofoil shapes to smooth the airflow away from the landing area aft. The 190,000shp machinery design of Design C was increased to 20,000shp for Design X but slightly reduced to 200,000 for Design X1, the final iteration; it would have been of an advanced, highly superheated design that was superior to the machinery fitted in Ark Royal. This would have given a speed in excess of 32 knots clean at deep load, and rapid acceleration.

The sixteen 4.5in guns were to be mounted in eight turrets, two on each quarter as in previous fleet carrier designs, but the requirement for them to fire across the deck was recognised as impractical and dropped. They would have been fitted in Mark 7 turrets, internally similar to the Mark 6 fitted to the majority of postwar British destroyers and frigates, but with a larger, 14ft-diameter roller path. Externally they would have been circular with a flat roof flush with the flight deck, like those in Implacable and Indefatigable. Like these earlier ships they would have been strong enough for aircraft to taxi over them or even to be parked with a wheel on the turret roof. Close-range armament included eight six-barrelled and seven single 40mm Bofors. Directors were mostly sited on or near the island so that they did not encroach on the rectangular shape of the flight deck or project above it, where aircraft wings might hit them. ‘Less than perfect’ fire control arrangements were accepted in the interests of optimal flying operations from the deck. The radar outfit would have been a considerable improvement on previous carriers, and was to include Type 960 air-warning, Type 982 intercept and Type 983 height-finding radars as well as Type 293M target indication radar and a number of target-tracking radars for the gunnery systems. Type 961 carrier-controlled approach radar for recoveries at night and in bad weather would also have been fitted.

Design X offered the largest flight deck yet designed for a British warship, at 938ft long overall, 6ft longer than that of the contemporary USS Midway, CV-41. However, there were fears that such a large ship would be unable to enter either Portsmouth or Devonport Dockyards, and alternative hulls 850ft and 750ft long were considered. Both offered less aircraft operating capability than Design X, and thus less value for money. A compromise hull 888ft long and 56,800 tons deep load, designated Design X1, was adopted. It was the shortest hull that could realistically have two side lifts, both on the port side, but was at the upper limit of size for the dry docks available in the Royal Dockyards. On 27 February 1945 DNC was tasked with completing the new design, and it was worked out in detail for Board approval on 12 April 1945.

The final design, X1, was intended from the outset to operate 30,000lb aircraft in large numbers, especially on long-range strike operations, and the Future Building Committee accepted that the requirements of aircraft operation dictated the design. This was in marked contrast to the armoured carriers of the Illustrious group, in which the ship design had dictated the size and type of aircraft and the way that they could be operated. It was appreciated that heavy aircraft, and especially jets, would need to be launched by catapult, and two were specified capable of launching 30,000lb aircraft at ends speeds of up to 130 knots in quick succession. This was a big ask, and Eagle, completed in 1951 with two BH5s, the most powerful British hydraulic catapults, could only achieve end speeds of 75 knots at this weight. The Admiralty’s early enthusiasm for the steam catapult is explained by the limitations on aircraft launch weights posed by legacy catapults.

The Admiralty decided in June 1944 that the flight deck should be constructed of mild steel plate on top of transverse beams that would provide the main strength, and that it should be covered with wood planking, following the USN practice. This gave a good non-slip surface that could easily be replaced after minor damage and aircraft accidents, but subsequent iterations of Design X1 may have reverted to a non-armoured steel deck, in line with the light fleet carriers. There would have been sixteen arrester wires reeved to eight operating units, each to be capable of stopping a 20,000lb aircraft at an entry speed of 75 knots. The three barriers would have had the same weight and entry speed parameters but a pull-out limited to 40ft. Movement of aircraft would have been easier than in any previous British design, with two centreline lifts, each 54ft long and 46ft wide, capable of lifting 30,000lb. The side lifts were 54ft long by 36ft wide and capable of lifting 30,000lb; aircraft positioned on them could overhang the ship’s side.

Their length was reduced from 60ft in Design X in order to support the sides of the lift opening on main transverse bulkheads. They were positioned one forward of the barriers and one aft and, during aircraft recoveries, it was intended that ‘sidetracking’ gear on the flight deck would allow aircraft that had just landed on to be moved on to the after side lift and struck down into the hangar quickly while the recovery continued. Others would taxi into Fly 1 ahead of the barriers, allowing large numbers of aircraft to be landed-on in a single recovery. The aircraft struck down could taxi and shut down their engines in the hangar parking area. Conversely, during launch operations, about seventy aircraft could be ranged aft on the flight deck and taxi forward to be catapulted; others would be run-up in the hangar, brought up to deck level on the forward side lift and moved into line with the catapults on the ‘side-tracking’ gear to be launched quickly. The ideas were novel, founded on experience, but were never tried because the Gibraltars were cancelled and the angled deck and steam catapults were adopted before newer ships were completed.

The guides for the deck-edge lifts were outside the main hull, and in their lower position at hangar-deck level they would have been vulnerable to wave damage. However, this seems not to have been a problem with the single side-lift in the USN Essex Class, and the novelty of the design may have caused DNC to overstate the potential problem. The side lifts were designed to be hinged up for entry into harbour and docking.

There were concerns about the effect of fire in an open hangar, and it was designed to be divided, if necessary, into four sections, each of which could be isolated by steel doors. Each section had its own lift which could be used to evacuate aircraft, and the normal spray arrangements were provided. DNC believed that it would be possible to continue flying operations in action while fire in a single section was brought under control. While the deck area of Malta’s hangar was larger than the upper hangar in Ark Royal, the funnel uptakes made significant inroads on the starboard side because the funnel uptakes were brought as far to port as possible to avoid the uptake problems that had contributed to the loss of Ark Royal in 1941.

Without armoured sides to the hangar there was little point in armouring the flight deck, although the question was raised again in May 1945, following hits by kamikaze aircraft on British carriers in the Pacific. Adding armour to the flight deck would have required another major redesign, and idea was finally rejected by the First Sea Lord in a statement to DNC on 20 May 1945. Armour was concentrated on the hangar deck and ship’s sides. Since the hangar deck was penetrated by access hatches to the deck below, the 4in armour was concentrated in the centre of the deck as an uncompromised ‘slab’ over the machinery. Armour of the same thickness was taken down the ship’s sides to create an armoured ‘box’ over the machinery spaces. The magazines for 4.5in ammunition and the steering gear compartment lay outside this armoured citadel and were armoured with their own 4in inverted ‘boxes’ with 3in end bulkheads. In addition the design included a number of transverse bulkheads to limit the effect of underwater explosions and the subsequent flooding. The machinery was divided into forward and aft boiler room groups separated by auxiliary machinery, with an engine room further aft. The ‘sandwich’ underwater protection, effectively an interior ‘bulge’ 20ft thick, was based on a complete re-examination of the subject, and differed from the that fitted in earlier fleet carriers. Designed to protect against charges up to 1,200lb exploding 10ft below the deep waterline, it featured a water/water/air ‘sandwich’ backed by a holding bulkhead installed at an angle to the vertical. This had the advantages of grading the protection to meet the increased damaging effect as depth increased, and making it easier to provide the desired level of protection forward and aft of amidships.

Suspensions and cancellation

The change to an open-hangar design led to delays in laying down these ships. The Admiralty Plans Division effectively suspended Africa and Gibraltar in its 1944 construction programme, and expected Malta to be laid down at the end of 1944 and New Zealand in April 1945. The suspended ships were to be undertaken only if the work did not interfere with orders for other urgently needed warships. A report by the Controller in October 1944 clearly had the end of the war against in Germany in sight and anticipated Japanese defeat by December 1946. He recommended that Malta and New Zealand should still be laid down and proceeded with slowly, but that Africa and Gibraltar should remain suspended. The Board gave its approval for the revised plan in November 1944. A Paper on the composition of the postwar navy was prepared by Plans Division on 29 May 1945; it made no changes, but the reality of postwar austerity forced the Admiralty to make drastic cuts in the following weeks.

On 29 September 1945 the Controller recommended the outright cancellation of Africa and Gibraltar, together with the four ships of the Hermes Class that had not yet been laid down and large numbers of cruisers, destroyers, sloops and submarines that were accepted as surplus to postwar requirements and on which little work had been done. The Admiralty Board gave its approval for the cancellations on 15 October 1945. Malta and New Zealand were eventually cancelled on 13 December 1945, and some writers have taken the delay to indicate that work on them might have started. If this is so, there can have been very little metal on the slipway and the later date probably indicates little more than the growing pressure on the Admiralty to reduce the size of its residual building programme in a period of extreme austerity, and to make slipways available for mercantile construction.

A lost potential?

The potential offered by the Gibraltar class design is enigmatic. After two years’ design effort they had reached the point where the design was mature enough to start in mid-1945, but three other large carriers and a number of smaller ones were actually being built and the Admiralty assumed, wrongly as it transpired, that the legacy Illustrious group, the largest of which were only two years old, could be modified at reasonable cost to operate the new generation of jet aircraft. A decade later it was realised that the armoured carriers, including Ark Royal, Eagle and Victorious, were extremely difficult and very expensive to adapt to take the new generation of carrier equipment including steam catapults, angled decks, larger radars and bigger operations rooms. With hindsight, the Maltas could have been modified in a shorter timescale at considerably less cost, and would have been more effective operational ships with the first- and second-generation jet strike fighters, just like the contemporary USN Midway Class. Their more modern machinery would also have given them a distinct advantage. It is difficult not to surmise that the RN would have been better off building two Maltas rather than the two Audacious Class ships that were retained and built to modified designs after 1945.