The air force component under the Imperial Japanese Navy during World War II. The birth of Japanese naval aviation occurred in 1912. The navy had been part of the Provisional Military Balloon Research Society, which had been established as a joint effort with the army. The army dominated the society, and the navy decided to withdraw and create its own organization, the Kaigun Kokujutsu Kenkyu Kai (Naval Aeronautical Research Association). This event would be a bone of contention between the army and navy for many years to come.

The naval association sent six officers to France and the United States to acquire seaplanes and learn to fly and maintain them. The operation was a success, and a new naval air station was established on the Oppama Coast near Yokosuka. Within the year, the Imperial Japanese Navy commissioned their first seaplane tender, the Wakamiya Maru.

In 1916, the first Navy Air Corps was activated, the Yokosuka Kokutai. In 1917, the first completely Japanese designed aircraft was built at the Yokosuka naval arsenal.

After World War I, the navy became intrigued with the idea of launching aircraft from ships. In June 1920, a deck was mounted to the Wakamiya Maru, and a Sopwith Pup was launched successfully from the deck. Then, in late 1921, the Hosho-the world’s first true aircraft carrier-was launched. Other ships had been modified to carry aircraft, but the Hosho was designed from the ground up to be an aircraft carrier.

It was not until 1932 that a major push was made to develop true carrier aircraft. The navy issued Specification 7-Shi for a carrier-based aircraft to be built. The navy had developed a system where it would submit a specification to a number of manufacturers, which would compete to have their design accepted for service. This specification was thought to be extremely important to the navy in its development of attack aircraft and fighters. However, only one aircraft, the E7K1 Alf, was placed into production in quantity. The failure was primarily due to high expectations and limited technology at the time. Two years later, navy specifications would be met, and the first of the dominant Japanese aircraft would start to appear in the arsenal.

It was about this time that the navy entered the second Sino-Japanese conflict. The results were outstanding. Japanese fighters and bombers forced the Chinese to withdraw their aircraft or lose them. There was also one additional benefit to the war with the Chinese. Beyond the experience gained, it gave the Imperial Japanese Navy a chance to further organize and develop effective air combat tactics. These would become very useful during the Pacific War.

Because of its collection of long-range aircraft and aircraft carriers, the navy would become responsible for all campaigns in the Pacific islands. It would also be responsible for the attack on Pearl Harbor.

By November 1941, the JNAF had ready about 1,750 frontline fighters, torpedo planes, and navy dive bombers, as well as over 500 flying boats or sea planes. These were deployable to forward sea bases and on six fleet carriers and four larger fleet carriers. The JNAF organized its planes into kokutai or air corps, usually of all one type, either of fighters or bombers. In 1941 all JNAF pilots were highly trained-at a minimum of 800 hours flying time-and some JNAF planes were superior to anything the U. S. Navy could then put into the air. That gave the JNAF an initial skills and numerical advantage in the Pacific War. However, Japanese reserves were insufficient to sustain a long war with the U. S. Navy: the entire aircraft industry produced under 1,500 military planes in 1937, which had to be divided with the Japanese Army. Production rose to 4,768 aircraft by 1940, again divided between the JAAF and JNAF. Just 5,088 military aircraft left the assembly lines in 1941. Japan also uniquely failed to expand its pilot training schools. It began the Pacific War with just 2,500 Navy pilots-the Sea Eagles-to fly its aircraft, and throughout the war suffered from a shortage of pilot training plans or facilities.

In the first six months of the war in the Pacific, the navy was extremely effective. Its experience in China and its organization made it a formidable foe. However, in June 1942 at Midway Island, U. S. carriers dealt the navy a heavy blow, sinking four aircraft carriers. This loss of ships and aircraft stopped the Japanese advance in the Pacific.

At this point of the war, it appeared that the industrial production of the United States and the abundance of pilots available to Allied forces could not be equaled by the Japanese. Japan was quickly running out of trained pilots as well as materials to produce aircraft and ships.

In October 1944, the Imperial Japanese Navy developed a new tactic: kamikaze attacks. A kamikaze would dive his aircraft, loaded with bombs, into Allied ships. The tactic did minimal physical damage given the number of aircraft and pilots that it sacrificed. Hostilities in the Pacific War continued until August 1945, when the order for surrender was given. This spelled the end of the Imperial Japanese Navy until the postwar years.

The Mitsubishi G4M medium bomber (“Betty”) entered service with the Japanese army early in 1941 and was involved in pre-World War II operations in China. It was designed in great secrecy during 1938-1939 to have the maximum possible range at the expense of protection for the crew and vital components, and it was mainly used in the bomber and torpedo-bomber roles. G4M1s were mainly responsible for sinking the British battleship Prince of Wales and battle cruiser Repulse off Malaya in December 1941. The G4M had an extraordinary range, but more than 1,100 gallons of fuel in unprotected tanks made the aircraft extremely vulnerable to enemy fire. The G4M2 appeared in 1943 and was the major production model, with more-powerful engines and even more fuel. Losses of the aircraft continued to be very heavy, and Mitsubishi finally introduced the G4M3 model late in 1943 with a redesigned wing and protected fuel tanks. A total of 2,479 aircraft in the G4M series were built.

The Kawanishi N1K1-J (“George”) evolved from a floatplane and was one of the best fighters of the Pacific Theater. Entering service early in 1944, it had automatic combat flaps and was outstandingly maneuverable, its pilots coming to regard even the F6F Hellcat as an easy kill. Its climb rate was, however, relatively poor for an interceptor, and the engine was unreliable. The later N1K2-J was redesigned to simplify production, and limited numbers entered service early in 1945. A total of 1,435 aircraft of the N1K series were built.

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) had several carriers at the start of the war, the air groups of which were weighted toward attack aircraft rather than fighters. Its aircraft were lightly built and had very long range, but this advantage was usually purchased at the expense of vulnerability to enemy fire. The skill of Japanese aviators tended to exaggerate the effectiveness of the IJN’s aircraft, and pilot quality fell off as experienced crews were shot down during the Midway and Solomon Islands Campaigns.

The Nakajima B5N (“Kate” in the Allied designator system) first entered service in 1937 as a carrier-based attack bomber, with the B5N2 torpedo-bomber appearing in 1940. The B5N had good handling and deck-landing characteristics and was operationally very successful in the early part of the war. Large numbers of the B5N participated in the Mariana Islands campaign, and it was employed as a suicide aircraft toward the end of the war. Approximately 1,200 B5Ns were built.

The Aichi D3A (“Val”) carrier-based dive-bomber entered service in mid-1940, and it was the standard Japanese navy dive-bomber when Japan entered the war. It was a good bomber, capable of putting up a creditable fight after dropping its bomb load. It participated in the attack on Pearl Harbor and the major Pacific campaigns including Santa Cruz, Midway, and the Solomon Islands. Increasing losses during the second half of the war took their toll, and the D3A was used on suicide missions later in the war. Approximately 1,495 D3As were built.

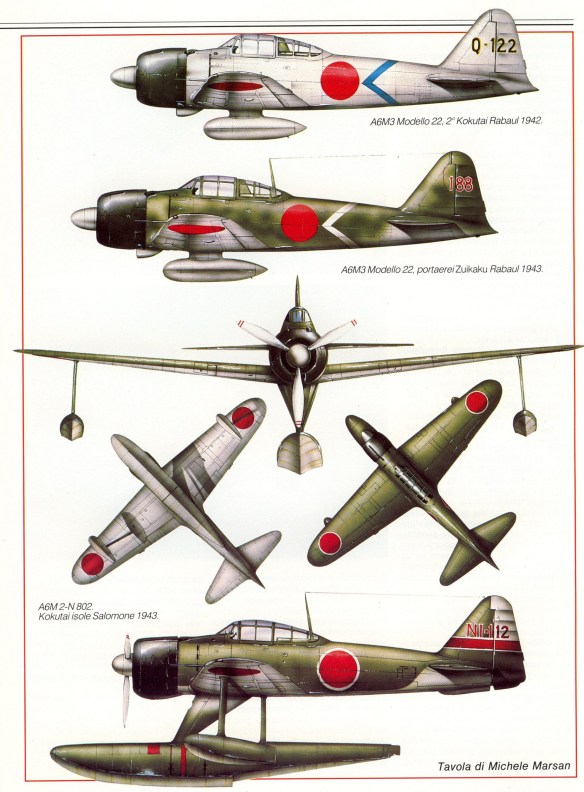

When it first appeared in mid-1940, the Mitsubishi A6M Zero was the first carrier-based fighter capable of beating its land-based counterparts. It was well armed and had truly exceptional maneuverability below about 220 mph, and its capabilities came as an unpleasant shock to U. S. and British forces. It achieved this exceptional performance at the expense of resistance to enemy fire, with a light structure and no armor or self-sealing tanks. Its Achilles heel was the stiffness of its controls at high speed, the control response being almost nil at indicated airspeed over 300 mph. The Zero was developed throughout the war, a total of 10,449 being built.

The Nakajima B6N (“Jill”) carrier-based torpedo-bomber entered service late in 1943 and was intended to replace the B5N, but the initial B6N1 was plagued with engine troubles. The B6N2 with a Mitsubishi engine was the major production model, appearing early in 1944. Overall, it was better than its predecessor but not particularly easy to deck-land. It participated in the Marianas Campaign and was encountered throughout the Pacific until the end of the war. A total of 1,268 were built.

The Yokosuka D4Y (“Judy”) reconnaissance/dive-bomber entered service on Japanese carriers early in 1943 and was very fast for a bomber. Initially assigned to reconnaissance units, it was intended to replace the D3A, but it was insufficiently armed and protected and suffered from structural weakness in dives. In common with most other Japanese aircraft, it was used for kamikaze attacks, and a D4Y carried out the last kamikaze attack of the war on 15 August 1945. A total of 2,819 D4Ys were built.

In addition to transporting troops and supplies, the four-engine Kawanishi H6K and four-engine Kawanishi H8K flying boats also served important roles as long-range reconnaissance aircraft, with the former having a maximum range of 4,210 miles and the latter having a maximum range of 4,460 miles.

Japan relied on three primary reconnaissance floatplanes during the war. The three-seat Aichi E13A, of which 1,418 were produced, was Japan’s most widely used floatplane of the war. Entering service in early 1941, it was employed for the reconnaissance leading up to the attack on Pearl Harbor, and it participated in every major campaign in the Pacific Theater, performing not only reconnaissance but also air-sea rescue, liaison transport, and coastal patrol operations. Introduced in January 1944 as a replacement for the E13A, the two-seat Aichi E16A Zuiun offered far greater performance capabilities but came too late in the war to make a significant difference, primarily because Japan’s worsening industrial position limited production to just 256 aircraft. Based on a 1936 design that underwent several modifications, the two-seat Mitsubishi F1M biplane, of which 1,118 were produced, proved to be one of the most versatile reconnaissance aircraft in Japan’s arsenal. Operating from both ship and water bases, it served in a variety roles throughout the Pacific, including coastal patrol, convoy escort, antisubmarine, and air-sea rescue duties, and it was even capable of serving as a dive-bomber and interceptor.

The three-seat Nakajima C6N Saiun, of which 463 were produced, was one of the few World War II reconnaissance aircraft specifically designed for operating from carriers. With a maximum speed of 379 mph, a maximum range of 3,300 miles, and service ceiling of 34,236 ft, the C6N proved virtually immune from Allied interception. Unfortunately for Japan, it did not become available for service until the Mariana Islands Campaign in the summer of 1944.

The twin-engine, two-seat Mitsubishi Ki-46, of which 1,742 were produced, served as Japan’s primary strategic reconnaissance aircraft of the war. Entering service in March 1941, the Ki-46 was one of the top-performing aircraft of its type in the war with a service ceiling of 35,170 ft, a range of 2,485 miles, and a maximum speed of 375 mph. This aircraft was first used by the Japanese Army in Manchukuo and China, where seven units were equipped with it, and also at times by the Japanese Imperial Navy in certain reconnaissance missions over the northern coasts of Australia and New Guinea.

Although Japan employed a variety of multipurpose aircraft, such as the Nakajima G5N Shinzan and the Tachikawa Ki-54, for transporting troops and supplies, it relied primarily on four main transport aircraft during World War II: the Kawanishi H6K flying boat, the Kawanishi H8K flying boat, the Kawasaki Ki-56, and the Mitsubishi Ki-57.

When Japan entered the war, the four-engine Kawanishi H6K served as the navy’s primary long-range flying boat. Although used at first primarily for long-range reconnaissance, it was soon relegated to transport duty because of its vulnerability to Allied fighters. Capable of carrying up to 18 troops in addition to its crew, the H6K remained in production until 1943. Of the 217 constructed, 139 were designed exclusively for transport.

The four-engine Kawanishi H8K entered service in early 1942 and gradually replaced the Kawanishi H6K. While it also served in a variety of roles, its transport version, the H8K2- L, of which 36 were built, could carry up to 64 passengers. With a cruising speed of 185 mph and a range of up to 4,460 miles, it was well-suited for the Pacific Theater, and its heavy armament afforded better protection than the H6K.