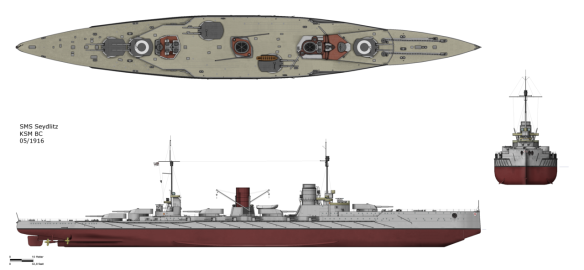

Seydlitz, heavily damaged during the battle of Jutland and attempting to limp home

The Skagerrak [Jutland] Battle

At 03.00 on 31 May 1916 there was light rain and a light NW wind in Schillig Roads as Seydlitz weighed anchor and steered out to sea in accordance with Operational Order 6, travelling as tactical number 3. (Summer time was used in the Seydlitz war diary, but the times here have been changed to MEZ/CET for clarity.) The highlights of the Seydlitz battle were as follows:

The detonation penetrated all three layers – that is outer skin, wing passage bulkhead and inner bulkhead – and the actual hole was from approximately frames 130 to 137, and went from the lower edge of the armour to about 4m below, being 90sq m in size. A wider area of the outer skin was indented. The armoured deck above the torpedo room had held firm, and whilst the starboard torpedo tube was displaced there was hardly any damage to the port tube.

Of six torpedoes stored in the broadside torpedo room none detonated, even though torpedoes 5038, 5097 and 5196 had their heads damaged and the air flask of 5097 blew up. On the other hand, torpedo 5036, charged to 2400psi, remained intact. None of the battle pistols, or fuses, of the torpedoes detonated, even though they were thrown around and damaged. These results were a relief for the Torpedo Inspectorate.

The main cause of flooding was sprung hatches and doors, leaking ventilation ducts, speaking tubes, sprung seams and sheared rivets. The large-capacity ‘leak’ pumps could not be used because the valves for the drainage pipes could only be accessed from the lower platform deck in compartment XV, which was underwater. Some rooms were drained with two portable drainage pumps, a ‘colonial’ pump and the drinking water pump. The total list was two to three degrees to starboard. Because the detonation occurred during a change of watch in the torpedo room there were a disproportionally high number of casualties, with eleven crew killed.

Commenting on 18 May Vizeadmiral Hipper said that there could be no question of blame as the waters Seydlitz was traversing were regarded as being free of mines. He commented that personnel fleeing the damaged area had left doors open and this had increased the effect of the mine hit. He said that underwater areas outside the protection of the torpedo bulkhead should not be occupied unless necessary and therefore continuous occupation of the torpedo room was not required. Once again it had been found that air ducts and speaking tubes below the waterline had exacerbated flooding, but the armoured deck had limited the effect of the detonation upwards. Vizeadmiral Scheer endorsed Vizeadmiral Hipper’s comments.

From 25 April – 18 May Seydlitz was in the floating dock in Wilhelmshaven undergoing repair. At 17.30 on 18 May the Panzerkreuzer was undocked and made fast at berth A5, where she remained until 23 May when she passed out of the lock and went to Schillig Roads and anchored. A flooding trial revealed the inadequacy of the repairs carried out by the imperial dockyard. The flooding in the transverse and wing passage bulkheads was so extensive that a new repair was required. So at 22.45 Seydlitz anchored in Wilhelmshaven Roads and ran into the imperial dockyard the following morning at 05.00. The repairs continued from 24–29 May, when the cruiser ran out to Schillig Roads at 07.30 and after a short trial trip dropped anchor. A sub-calibre shoot followed.

The German leadership had been planning another coastal raid, this time on Sunderland, and issued orders for the attack on 18 May; however, Vizeadmiral Scheer would not conduct the raid until Seydlitz was again combat ready. Therefore the operation was postponed from its original date of 23 May until later in the month. Vizeadmiral Hipper was also unhappy about the condition and delay with Seydlitz, and wrote: ‘Minor leaks were still present, and the starboard broadside tube was missing. The ship was not completely clear for battle. I preferred to participate in the operation in a fully combat ready ship, Lützow. So I went to this ship.’ On 30 May there was still no chance of aerial reconnaissance for the fleet by airships, and therefore Vizeadmiral Scheer decided on an alternative plan to interdict and sink merchant shipping in the Skagerrak, and it was this decision that led to the Skagerrak Battle.

The Skagerrak [Jutland] Battle

At 03.00 on 31 May 1916 there was light rain and a light NW wind in Schillig Roads as Seydlitz weighed anchor and steered out to sea in accordance with Operational Order 6, travelling as tactical number 3. (Summer time was used in the Seydlitz war diary, but the times here have been changed to MEZ/CET for clarity.) The highlights of the Seydlitz battle were as follows:

16.50: Open fire.

16.55: First hit in compartment XIII.

16.57: Hit in the working chamber of turret C.

17.26: Seydlitz and Derfflinger destroy Queen Mary.

17.41: High Sea Fleet in sight.

17.57: Torpedo hit to starboard.

18.10: Hit on turret B.

19.50: Battle pause.

20.16: Further battle to port, further hits.

20.40: Vizeadmiral Hipper approaches the ship to come aboard.

21.30: Hit near bridge kills five.

1 June 1916

00.45: Three British battleships avoided by using British recognition signal.

At 15.25 on 31 May the small cruiser Frankfurt reported a smoke cloud in the NW, so that at 15.30 a signal was made for a course WSW at 18kts. At 15.33 speed was increased to 21kts and two minutes later ‘clear ship for battle’ was sounded. Soon Elbing reported that she was in battle and the I AG steered toward her position, increasing speed to 23kts and then 25kts. At 16.20 five smoke clouds, apparently from large ships, were sighted to the west. Course was changed to NW at 18kts. At 16.30 two battlecruisers with tripod masts were sighted and two minutes later the signal was received: ‘Fire distribution from the right.’ This meant that Seydlitz would take the third ship from the right under fire, a battlecruiser of the Lion class. At 16.35 Seydlitz’s war diary reported: ‘Formation of the enemy line ahead: 3 Lions, Tiger, 2 Indefatigables. Behind them at a great distance 4 Malaya’s [sic].’ At 16.38 speed was reduced to 15kts, and then, as the enemy was observed to change course, a turn was made to the SSE at 16.45. At 16.50 Seydlitz opened fire, direction 110°, range 150hm, her target was the third British ship from the left, Queen Mary. At 16.53 speed was increased to 21kts and at 16.54 the medium-calibre guns opened fire on some British destroyers.

The I Artillerie Offizier Korvettenkapitän Foerster described the opening salvos:

Immediately after we had fired our first salvo I saw on our opponent the flash of muzzle fire, and shortly afterwards their first greeting to us arrived. And now the battle raged, a deafening noise, the thunder of our gunfire and of the other ships in our line, mixing with the crashes around us from shells bursting in the water. The sea boiled, the surface was troubled by the innumerable splashes of splinters, and now and then the water columns reached turret high, climbing vertically after the detonation of heavy shells. We had quickly caught our opponent, Queen Mary; one salvo over, the next short, and held them in rapid salvo fire. Then, approximately ten minutes after the opening of fire, Habler reported to me by telephone, ‘Turret Caesar is not answering; from the speaking tube of turret Caesar smoke is penetrating the artillery central.’ This was exactly the same report that I had received on January 24 on the Dogger Bank, also at the beginning of the battle. I therefore knew what this report signified. The cartridges were in flames, and the turret was put out of action.

Almost mechanically I gave the order: ‘Flood magazine of turret C.’ This would put the chamber under water, and prevent further incidents.

At 16.55 Seydlitz received her first hit, in compartment XIII, to starboard forward. The electrical switch room fell out. Two minutes later C turret barbette was struck and the working chamber was penetrated, and a powder fire resulted, just as with turret D at the Dogger Bank. However, the new precautions prevented a spread of the catastrophic powder fire. At 17.10 the enemy appeared to turn away and the range increased to 140hm, but meanwhile two more hits were received at 17.10 and 17.18. The latter struck the port VI 15cm casemate and killed the entire crew, but the squadron chaplain, Pfarrer Fenger, who was in the casemate, survived. Speed was increased to 22kts and at 17.15 a great explosion was observed on the fifth enemy ship, as Indefatigable blew up. At 17.26 Seydlitz was firing on the third enemy ship, direction 88°, range 135hm, when suddenly this opponent likewise blew up. A smoke-and-flame column 600–800m high was observed with debris falling right and left. This marked the end of Queen Mary, which was also under fire from Derfflinger, and so Seydlitz changed target right onto Tiger. Shortly after, at 17.32, the four battleships of the Malaya class approached to starboard aft and opened fire, and at 17.41 the German main body came in sight and eight minutes later opened fire. At 17.52 the signal was made for a turn onto course north, to a position at the head of the fleet. Then at 17.55 torpedo tracks were seen to starboard as battle was renewed with the British battlecruisers. At 17.57 a torpedo struck to starboard in compartment XIII, but the torpedo bulkhead held firm. From 18.06 to 18.10 three hits were counted, two in the forecastle and one on the face of Bertha turret, so that the right gun fell out.

From 18.10 there was a battle pause and stock was taken of the remaining munition. Turret A had 104 shots, B sixty-five shots, turret C had fallen out, D had 120 shots and turret E 100 shots. At 18.25 a signal was received to go over onto the enemy battleships. With a course NW, fire was opened on the third ship from the right, range 185hm. Nevertheless, it was difficult work, as Korvettenkapitän Foerster noted:

After a short pause we again went to the guns; the lighting had become very unfavourable for us, and the outlines of ships against the gradually darkening heavens were hardly recognisable, and only when they fired could we see the muzzle flash of their guns, although now the range was quite low. Many 38cm shells landed on and around us and we could hardly fight back as we couldn’t observe them. The heavy shells that struck close beside us in the water showered the ship with mountainous cascades. Time after time I had to send Obermatrosen Lange out of the command position to clean the object lenses of my periscope, and he would climb on top of the conning tower, unconcerned about the whizzing and crashing shells, and for a time at least observation was possible.

At 18.55 Seydlitz received two more hits in the forecastle from 15in calibre shells, which caused a fire. At 19.03 it was noted that flooding in the forecastle was causing a loss of buoyancy forward. Shortly after, at 19.06, there was action to starboard and Seydlitz turned onto S by W as the evening sun made observation of the enemy impossible, and at 19.30 fire was ceased as they could not see the fall of shot. At 19.44 steering had to be temporarily undertaken from the rudder room, as the vibration from a hit had caused the coupling of the upper rudder engine to fly off. Another short battle pause followed and the munition situation was ascertained as follows: turret A 101 shots remaining, B fifty-one shots, C turret fallen out, D turret 110 shots and E turret seventy shots. The right gun of turret A had the lower shell hoist in manual drive. At 20.03 a course was again taken to the east, towards the enemy, and shortly after battle resumed to port; however, Seydlitz had no clear target, though she was one herself. At 20.13 the Panzerkreuzers were ordered to attack the enemy, and a minute later were ordered to operate against the head of the enemy line. Between 20.00 and 20.30 Seydlitz was hit six times by enemy fire, whilst herself landing two shells on the battleship Colossus at 20.16. On Seydlitz there were two hits amidships, a hit on the aft searchlight bridge, a hit on the right barrel of E turret and a further hit on C turret. Shortly after, at 20.40, Vizeadmiral Hipper approached aboard a torpedo boat intending to board Seydlitz but when he learned of the condition of the ship he continued to Moltke. There was now another battle pause.

At 21.20 battle resumed with the British battlecruisers and then at 21.24 Seydlitz was hit amidships and further, at 21.28, was hit on the roof of turret D and on the admiral’s bridge. The first hit did little damage but the hit on the bridge killed five men and wounded another five, including the adjutant and navigation Offizier, Korvettenkapitän Düms. Korvettenkapitän Foerster wrote:

On the starboard command bridge I had had a sadder but touching moment: buried under his dead signal maats and gasts [mates and numbers] lay the adjutant, Leutnant zur See Witting, his battle signal notebook and secret signal book key wedged tightly under his arm. During the entire battle he and his men had stood on the open bridge next to the command position, so he could more readily see the signals from the flagship and relay them correctly. The last enemy shell had detonated in the vicinity of this group and had done horrible work to the poor men. They were all killed, except for Witting, and were horribly mutilated. I went to help Witting in his terrible condition and he was placed on a transport hammock – he still held his book, although both hands were shredded and a leg severed – he said to me: ‘The others first!’ In his helpless situation and despite his agony, he wanted help not for himself, but for the others, his signal personnel. He didn’t suspect his life was the only one saved from certain death.

The water did not constitute a danger to the ship if it could be kept out of the forward upper ship. This was not to be, however, as the large shell holes in the decks allowed water to enter above the armoured deck because the speed of the ship drew water over the forecastle, then because of the destruction of interior bulkheads and decks the water freely flooded the forecastle. A heavy shell-hit in compartment VIII on the citadel armour allowed an upper bunker to flood and the hole in the armour of the port IV 15cm casemate threatened to become a serious danger. It was estimated that there were 1,000 tonnes of water in the forecastle, and the large hole there was inaccessible and could not be sealed. The fight against flooding was limited to sealing rooms not already affected and sealing shot holes above the waterline as much as possible. Wooden mats, hammocks and wedges were used for the most part, but when the swell reached these positions the mats were soon loosened and washed away.

The flooding in the broadside torpedo room in compartment XIV could be held in check through continuous pumping through the main drainage pipe. In compartment XIII the rooms below the armoured deck, despite all attempts at sealing, gradually began to fill with water, which penetrated through the armoured deck via shot-through ventilation ducts and because of the lack of watertightness between the torpedo bulkhead and the armoured deck owing to the torpedo hit. This important compartment possessed no connection with the main drainage system. Boiler room V also leaked but this could be controlled.

The bow of the ship continued to sink deeper. The speed had to be reduced from 20kts to 15kts, then 12kts because the bow wave came over the forecastle and the trim of the ship made the control of her more and more difficult. A critical moment arrived, as the water on the Batterie deck came over the transverse bulkhead of the citadel armour, compartments XIII/XIV, and penetrated the rooms of compartment XIII above the armoured deck. The water was flooding into the armoured midships. The available portable ‘leak’ pumps could not cope with the quantities of water or failed after a short time. The broadside torpedo room made water but use of the pumps and drainage system stemmed the tide and the water level fell. However, the remainder of the forecastle gradually filled.

At 06.45 on 1 June the torpedo central position had to be abandoned owing to the great water pressure on the bulkhead. Seydlitz tried to increase speed to join up with the end of the II Squadron but at over 15kts water came over the forecastle, so that speed was gradually reduced, at first to 10kts, then to 7kts. Derfflinger and Posen ran past on the starboard side.

At around 08.40 in square 158 beta, the two gyro compasses failed so Seydlitz requested the leader of the II AG to dispatch a cruiser to navigate her through the Amrum Bank passage. The magnetic compass had suffered a deviation change and was unreliable. All the charts were either lost, damaged (by the blood of those wounded in the conning tower) or were underwater. Whilst five minesweepers took over anti-submarine security, Pillau arrived and followed in the wake of the Panzerkreuzer. By 09.40 the ship had a draught forward of 13m and navigating through the Amrum passage was thought impossible, but steering to the west of Amrum Bank was abandoned and a renewed attempt was made to the east of the bank.

Shortly after a request had been sent for two pump steamers and material to seal the leaks, towards 10.00 the ship became stuck fast abeam Hörnum-Sylt in a depth of 13.5m. To raise the bow as high as possible, the middle and port aft trim cells and the port wing passage were flooded, and at the same time the list to starboard was reduced. With these measures, and the rising tide, the ship came free again.

At 11.25 Seydlitz passed through the Amrum passage but by 13.12 the situation was becoming critical and the starboard list had changed to a port list because of bunkers flooding, increasing to 8°. Stability was considerably reduced. At 16.00 Seydlitz was in square 164 beta and steering stern ahead along the coast in water 15m deep. Towards 18.00 the starboard aft wing passage was flooded, to combat the list. Now more than 5,300 tonnes of water were in the ship and the list was still 8° to port. The difference between the theoretical heeling and that observed was reduced by the loss of stability and buoyancy. Shortly after this the two pump steamers from the imperial dockyard at Wilhelmshaven, Boreas and Kraft, came alongside. Boreas pumped from starboard from compartment XIII, above the armoured deck; Kraft was to pump out the magazine of turret A, however it was impossible to get her pumps to suck. This failure was partly due to the steamer being fitted with centrifugal pumps, and partly due to the suction hoses being of too great a diameter.

Between 18.00 and 19.00 Pillau made a futile attempt to tow Seydlitz over the stern and she continued going stern ahead. Pillau continued to pilot the ship and at dawn on 2 June she was taken in tow by two dockyard tugs. However, the wind freshened to force 8 from the NW and the sea began to run unpleasantly for the ship. Pillau made a lee for the ship, Boreas pumped from the forward port casemate and Kraft calmed the rough seaway by laying an oil slick.

At 08.45 on 2 June Seydlitz anchored in the vicinity of the outer Jade light vessel and Pillau and the minesweepers were detached. The auxiliary hospital ship Hansa came alongside and took off the wounded, although Pfarrer Fenger was disappointed he could not remain aboard until the ship reached Wilhelmshaven. A tug took those killed who could be reached in the hull to Wilhelmshaven. At high water Seydlitz weighed anchor and moved to Schillig Roads, but the powerful cross currents caused the ship to ground from 16.20 to 21.00. Around midnight Seydlitz passed through the net barrier off the Jade going sideways.

About 04.25 on 3 June the cruiser anchored in Vareler Deep off Wilhelmshaven and as the dock could only accommodate a draught of 10.5m, work began on sealing and lightening the ship. At 15.30 on 6 June she entered the southern lock with a draught of 14m and the work continued there until 13 June, when the ship was moved to the large floating dock with a draught of 10.45m forward and 8.55m aft.