The Fetterman Fight: The Pursuit and Ambush

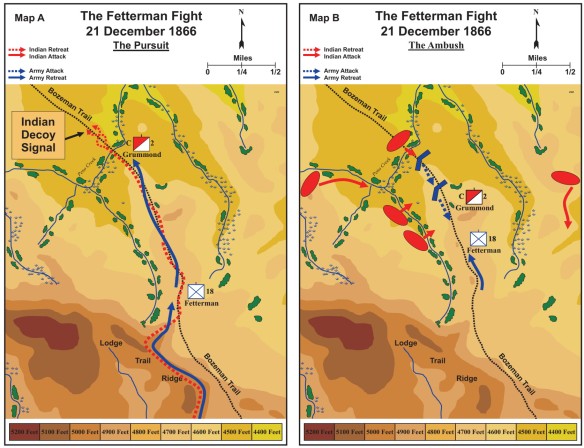

Although the details of the fight are uncertain, it appears that the mounted troops and the foot infantry became separated. Whether Fetterman gave the order or Grummond was acting on his own will never be known, but the cavalry, along with a small detachment of mounted infantry and two civilians, moved ahead of the infantry soon after passing over Lodge Trail Ridge. Indian decoys demonstrated tauntingly before the relief column and lured them toward Peno Creek. Based on his past tendency for impetuous action, Grummond was probably anxious to come to grips with the foe.

At the foot of the slope, however, hundreds of Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho Indians sprang their trap. Indian accounts indicate that the Cheyenne were hiding to the west of the ridge in the trees, scrub, and depressions around Peno Creek and that the Sioux and Arapaho were in hiding to the north along Peno Creek and to the east of the road behind the next ridge.

Grummond’s mounted detachment retreated back up the hill. Wheatley and Fisher, the two civilians, along with several veterans, dismounted and defended a small outcrop of rocks. These experienced frontiersmen understood that it was fatal to attempt a mounted retreat from attacking Indian horsemen. Wheatley and Fisher apparently used their repeating rifles to good effect before succumbing. Carrington later claimed in his report that there were 60 pools of blood surrounding the position. Nevertheless, the two civilians bought with their lives the time Grummond needed to rally his mounted troops at the top of the hill.

The Fetterman Fight: The Cavalry Fight and Fetterman’s Last Stand

The mounted troops retreated southward up the ridge to take cover behind a small hill. It appears that Grummond fought a dismounted delaying action here. Their skirmish line fired to the north and down the ridge to both sides. At some point, Grummond attempted to fall back to the south along the road toward the infantry. Nevertheless, the retreat disintegrated into a rout, and most of the mounted soldiers were chased down by the Indians before they could rejoin the Infantry (see map B). Grummond’s body and several others were found scattered along the road between the cavalry skirmish line and the final infantry position. Indian accounts speak of a “ponysoldier chief” who was killed on the road and whose men then gave way and fled up the ridge. Other Indian accounts speak of a soldier chief on a white horse that fought a brave delaying action, cutting off an Indian’s head with a single stroke of his saber. One of the last soldiers to die along the cavalry skirmish line was Adolph Metzger, a German-born bugler and Army veteran since 1855. Metzger fended off his assailants with his bugle until the instrument was a battered, shapeless mass of metal and his body was bleeding from a dozen wounds.

Fetterman, Brown, and 47 other soldiers, mostly infantry armed with Civil War era muzzle-loading rifle muskets, rallied at a cluster of large rocks further up the ridge. American Horse and Brave Eagle, both Oglala Sioux warriors, claimed that the soldiers fought hard and resisted several attempts to overrun their positions. However, Fetterman’s infantry were hopelessly outnumbered and had little chance of holding out. Eventually, they were overwhelmed, and all were killed. At the fort, Carrington heard the heavy firing beyond the ridge. Fearing the worst, Carrington ordered Captain Tenador Ten Eyck to take what men could be spared from the remaining garrison to assist Fetterman. By the time Ten Eyck reached the hills overlooking the fight, it was too late to save Fetterman’s doomed command.

After the battle, Carrington displayed remarkable determination in recovering the bodies of Fetterman’s men even though he feared that the Indians would attack and overrun the drastically undermanned fort. He asked for and received a volunteer to carry news of the disaster to Fort Laramie. Arriving at Fort Laramie during a Christmas night ball, the volunteer, John “Portugee” Phillips, had ridden 235 miles in 4 days to report the disaster. On 26 December, General Phillip St. George Cooke, Carrington’s commanding officer, ordered Lieutenant Colonel Henry W. Wessells, Carrington’s subordinate at Fort Reno, to take command of the relieve expedition and assume overall responsibility for all three forts on the Bozeman Trail. The new commander diligently applied himself to improving morale at Fort Phil Kearny, but the garrison suffered greatly from the lack of supplies and the intense cold. The Indians also suspended their operations against the fort because of the extreme winter conditions. Both sides waited for spring to resume the contest for control of the Bozeman Trail.

The Hayfield Fight, 1 August 1867

In the spring and summer of 1867, the Indians resumed their harassment against Forts C. F. Smith and Phil Kearny. None of the attacks had been seriously pressed, and neither side had sustained significant casualties. In July 1867, Red Cloud gathered his coalition of Indian tribes in the Rosebud Valley for the sacred Sun Dance and to discuss the next move against the Bozeman Trail forts. The tribal leaders probably fielded as many as 1,000 warriors, but the loose confederation of tribes could not agree on which fort to attack and ended up splitting their forces. The majority of the Cheyenne, with some Sioux, moved against Fort C. F. Smith while the rest of the Sioux and some Cheyenne decided to attack a woodcutting party near Fort Phil Kearny.

Probably because action against the forts had been sporadic, the Indians were unaware that, early in July, a shipment of new M-1866, Springfield-Allin, .50-70- caliber, breech-loading rifles had arrived at the forts. The Springfield-Allin was a modification of the .58-caliber Springfield muzzle-loader, the standard shoulder arm of the Civil War. Although single shot, the new weapon, which used the Martin bar-anvil, center-fire-primed, all-metallic .50-caliber cartridge, was highly reliable and could be fired accurately and rapidly. Along with the rifles came more than 100,000 rounds of ammunition.

Both forts, C. F. Smith and Phil Kearny, were sufficiently strong, having no fear of a direct attack against their bastions. However, the forts did have exposed outposts. At Fort C. F. Smith, it was the hayfield camp located 2.5 miles to the northeast of the fort. At the hayfield camp, the contract workers had erected an improvised corral out of logs and brush as a protected storage area for their equipment and animals and as a defensive position, if needed. Nineteen soldiers, commanded by Lieutenant Sigismund Sternberg, guarded the six haycutters in the hayfield.

On the morning of 1 August 1867, the Indians attacked the detail working the hayfield. The combined Army and civilian force quickly took refuge in the corral and, except for the lieutenant, took cover behind the logs that lined the perimeter of the corral. Lieutenant Sternberg, with formal European military training and experience in both the Prussian and Union armies, did not consider it proper military protocol for officers to fight from the prone position and so decided to fight standing up. The 29-year-old lieutenant had only been at Fort C. F. Smith for 7 days and had no prior experience fighting Indians.

Though the actual Indian strength is unknown, it probably approached 500. The initial attack occurred sometime around noon. The Indians made several dashes at the corral hoping to lure the soldiers into chasing them. After that tactic failed, they conducted a mass charge on the corral. The warriors expected a volley of fire from the soldiers followed by a pause for the soldiers to reload their clumsy muzzle-loaders. During that pause, the attackers planned to rush in and overrun the corral. However, the pause never occurred, because the soldiers were able to quickly reload their new rifles. Even though the soldiers had not become thoroughly accustomed to their new weapons, their mass firepower threw back the attack. During the attack, Indian fire killed Lieutenant Sternberg with a shot to the head. Indian fire also seriously wounded Sternberg’s senior NCO in the shoulder. Therefore, command was assumed by Don A. Colvin, one of the hayfield civilians who had been an officer during the Civil War.

With the failure of the first attack, many of the Sioux and Cheyenne warriors took cover on the bluffs 300 yards south of the corral and, from that position, kept the corral under fire until late into the day. The second attack came from the bluffs and was again repelled by the soldiers’ massed fire. Twice more that afternoon the Indians launched mounted assaults from the high ground hoping to overrun the defenders. Each sweeping charge was stalled by the defenders’ continuous fire forcing the Indians to retreat. The Indians commenced their final attack against the south wall of the corral on foot. The attackers managed to wade the shallow creek but were unable to force their way up to the corral wall.

Back at the fort, Colonel Luther P. Bradley, with 5 companies of available Infantry (10 officers and 250 soldiers), could neither see nor hear the fighting at the corral. News of the attack came sometime after lunch when the wood train, which had been working southwest of the fort, reported that they could see a large number of Indians attacking the hay detail. At first, the colonel was reluctant to send help. Perhaps he feared a Fettermanlike ambush was awaiting the relief party. However, he did send out a mounted reconnaissance at about 1530 which quickly returned to the post and reported the seriousness of the situation. The reconnaissance report, along with a desperate plea for help from a courier who had managed to break out of the hayfield corral and make a dash for the fort, prompted the colonel to organize a two-company relief force to send to the aid of the hayfield fighters. The appearance of reinforcements, at about 1600, and especially the exploding case shot of their accompanying howitzer, convinced the attackers to give up the assault and withdraw. Colvin and his outnumbered defenders had held their position for more than 6 hours. The combined Army/civilian force had sustained three killed and three wounded. Although the Army estimated 18 to 23 warriors killed, the Indians only acknowledged 8 killed and several wounded.

The Wagon Box Fight, 2 August 1867

The exposed outpost at Fort Phil Kearny was the pinery located 6 miles to the west of the fort. Captain James Powell’s C Company, 27th Infantry provided the guard for the civilian woodcutters at the pinery. The soldiers guarding the wood camps operated out of a corral located on a plateau between Big and Little Piney Creeks. The corral was made by removing the boxes from atop the running gear (wheels and axles) of wagons. The running gear would then be used to haul logs from the pinery to the fort. The boxes, approximately 10 feet long, 4½ feet wide, and 2½ feet high, were then placed in a rectangular formation approximately 60 feet by 30 feet. Two wagon boxes, with canvas still attached, held the rations for both soldiers and civilians and sat outside the corral.

The Indians, their martial ardor stirred by the recent religious ceremony, attacked the soldiers at the corral on the morning of 2 August 1867. Powell had already sent out the working parties when the Indians attacked. A small number of warriors crossed the hills to the west of the corral and attacked the woodcutter camps on the Big and Little Piney Creeks. The warriors then raced onto the plateau and captured the mule herd. The war chiefs had hoped the soldiers at the corral would rush out from their improvised wagon box fortress to be ambushed in the open. Instead, Captain Powell kept his men under control and by 9 o’clock had 26 soldiers and 6 civilians gathered into the corral. At this point, the war chiefs had no choice other than to attempt a mass attack against the soldiers. While Indian spectators gathered on the surrounding hills, mounted warriors made the first attack charging the corral from the southwest. The warriors expected the soldiers to send one volley of fire followed by a pause to reload their muzzle-loaders, allowing plenty of time for the Indians to overwhelm the defense. However, the soldiers were able to reload their new rifles quickly, and their continuous fire blunted the attack. The Indians, instead of closing in, circled around the corral using their horses as shields and then quickly withdrew behind the ridge to the north.

After the mounted charge failed, the war chiefs organized their warriors for an assault on foot. The second attack came from behind the ridge to the north. This time the warriors charged on foot while mounted warriors demonstrated to the south. The foot charge surged to within a few feet of the corral before it stalled under the continuous fire of the soldiers and fell back to take cover. At the same time, snipers hidden behind a rim of land fired into the corral. It was these snipers who inflicted most of the casualties suffered by the soldiers in the day-long fight. One of those casualties was Lieutenant John C. Jenness who had been repeatedly told to keep his head down. His reply that he knew how to fight Indians echoed just moments before he fell dead with a head wound. The third attack came up and over the rim of land just to the northeast of the corral. In this attack, the Indians’ charge almost reached the wagon boxes before the soldiers’ heavy fire forced them back again. The fourth and final attack came from the southeast. In this attack, the warriors attempted another mounted charge, but again failed to close with the soldiers.

The fight lasted into the early afternoon. The garrison at Fort Phil Kearny could hear the firing, but fearing an ambush, was reluctant to send support. Major Benjamin Smith did finally leave the fort with a relief column of 102 men and a mountain howitzer. Nearing the wagon box battleground, Smith fired his howitzer which resulted in the dispersal of the Indian attack. At a cost of three soldiers killed and two wounded in the wagon box perimeter, the soldiers had held off hundreds of Indian braves. Powell modestly credited his successful defense to the rapid fire of the breech-loading rifles, the coolness of his men, and the effectiveness of his position. The Indians also claimed victory in the fight. Their warriors had successfully destroyed the woodcutter camps and burned several wagons. They had also captured a large mule herd and killed several soldiers. Precise Indian casualties are unknown; Powell estimated 60 dead and 120 wounded. The actual casualties were probably much less.

In spite of the Army’s small victories at the wagon box corral and the hayfield fight, the days of the Bozeman Trail were numbered. After 8 months of negotiations, the majority of the Indian chiefs finally agreed to the terms of a new treaty, but it was not until November 1868 that Red Cloud signed the document at Fort Laramie. The 1868 treaty met almost all of the Sioux demands, including the abandonment of the three forts in the contested area and the closing of the Bozeman Trail. In August 1868, the last US Army units departed Forts Phil Kearny and C. F. Smith. Even before the Army columns were out of sight, the Sioux and Cheyenne set fire to the remaining buildings and stockades and burned them to the ground.