The Bozeman Trail and the Connor Expedition

The discovery of gold in western Montana in 1862 around Grasshopper Creek brought hundreds of prospectors to the region. Nearly all of these fortune seekers had come up the Platte Road, the northern fork of the old Oregon-California Trail, and moved into Montana from the west. Others worked their way up the Missouri River as far as Fort Benton, then came down into the goldfields from the northeast. In 1863, two entrepreneurs, John Bozeman, a Georgian who had arrived on the frontier only 2 years earlier, and John Jacobs, a veteran mountain man, blazed a trail from the goldfields to link up with the Platte Road west of Fort Laramie. This route cut through Bozeman Pass east of Virginia City, crossed the Yellowstone and Bighorn Rivers, ran south along the east side of the Bighorn Mountains, crossed the Tongue and Powder Rivers, then ran south through the Powder River country to join the Platte Road about 80 miles west of Fort Laramie. It reduced by nearly 400 miles the distance required by other routes to reach the goldfields. However, the trail cut through prized hunting land claimed by the Teton Sioux and their allies along the Powder River. Travelers along the Bozeman Trail soon found themselves under fierce attack by hostile Indians.

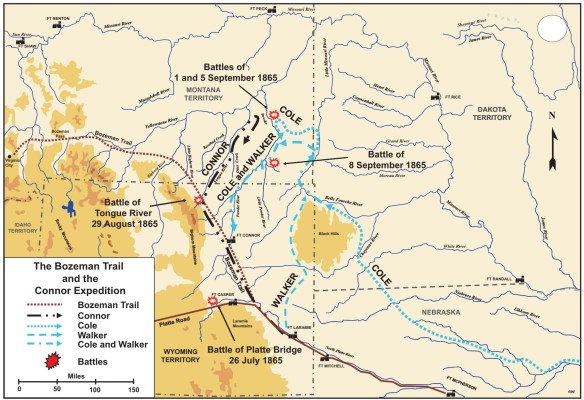

In 1865, responding to an Indian attack against the Platte Bridge near modern Casper, Wyoming, and to demands by the emigrants for protection, the US Army sent three converging columns under the command of General Patrick E. Connor into the region. Colonel Nelson Cole commanded the Omaha column that consisted of 1,400 volunteer cavalry. Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Walker commanded the second column with 600 volunteer cavalry. Connor commanded the third column. His force consisted of 558 soldiers and another 179 Indian scouts. The strategy called for the three columns to rendezvous in early September on Rosebud Creek.

Connor reached the Upper Powder River by mid-August. He established Fort Connor then continued northwest in pursuit of the Indians. On 29 August he found and attacked the Arapaho village of Black Bear on the Tongue River near modern Ranchester, Wyoming. His attack overran the village and captured the pony herd. However, after completing the destruction of the village, several spirited Indian counterattacks convinced Connor that he should withdraw his outnumbered troops. Then, in the midst of early winter storms, Connor moved north to locate Cole’s and Walker’s columns.

Meanwhile, Cole had marched just north of the Black Hills and headed up the Belle Fourche River where he linked up with Walker’s column on 18 August. Initially, the two columns continued to push deep into Indian lands until they grew dangerously low on supplies and decided to move toward the Tongue River and link up with Conner. On 1 September, a large Cheyenne war party attacked the columns altering Cole’s decision to move toward the Tongue River. Instead, they headed down the Powder River hoping to replenish their supplies with the abundant game known to be in the Yellowstone River valley. The night of 2 September inflicted early winter storms on the columns. More than 200 of Cole’s horses and mules, already weakened by hunger, died from exposure and exhaustion. Again, Cole changed his direction of march and decided to return to Fort Laramie for provisions. On the morning of 5 September, Cole and Walker unknowingly stumbled into the vicinity of a large village near the mouth of the Little Powder River. The village was an unprecedented gathering of Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and Southern Cheyenne. More than 1,000 Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors swarmed out of the village to attack the columns. The battle raged for 3 hours before the still undiscovered village moved safely out of the way, and the Indians broke off the fight. Then again on 8 September, the exhausted and starving troops unwittingly threatened the village. The Indian rearguard easily delayed the soldiers and the village escaped a second time.

Over the course of the next 12 days, the columns continued to plod along. Each day dozens of horses and mules died of starvation. The Indians hovered around the columns like vultures and, had it not been for the detachment’s artillery, probably would have been more troublesome to the troops. On 20 September, Cole and Walker’s troops straggled into Fort Connor. Connor’s equally exhausted troops joined them on 24 September. The expedition had failed to subdue the tribes and, instead, had emboldened the Sioux to continue their determined resistance to any white incursion into Powder River country. Nonetheless, the presence of Fort Connor on the Bozeman Trail encouraged increased immigrant travel along the route and further amplified their demands for protection.

The Bozeman Trail Forts, 1866–68

The failure of the Connor Expedition prompted the government to seek a diplomatic solution, and, in June 1866, while a number of the Powder River chiefs were at Fort Laramie negotiating a treaty to allow safe passage through the Powder River country, Colonel Henry B. Carrington led the 2d Battalion, 18th Infantry, toward the Bozeman Trail. His orders required him to garrison Fort Reno, formerly Fort Connor (built the previous year by General Connor), and to establish two new forts along the Bozeman Trail. From those forts, he was to provide protection and escort for emigrant travel into the Montana Territory. Considering the number of chiefs participating in the peace negotiations, the prospect for an early settlement seemed good, and the Army did not expect Carrington’s mission to involve significant combat actions. Consequently, in addition to the 700 troops of the 18th, more than 300 women, children, sutlers, and civilian contractors accompanied Carrington. The column included 226 mule-drawn wagons, the 35-piece regimental band, 1,000 head of cattle to provide fresh meat for the force, and all the tools and equipment necessary to create a community in the wilderness.

Carrington left Fort Laramie fully confident that he would be able to accomplish his mission without difficulty. He seemed to be well suited for his mission based upon his proven merit as a planner and organizer. A graduate of Yale, he was a practicing attorney when the Civil War began in April 1861. He volunteered immediately for service and secured a commission as colonel of the 18th Infantry on its organization in May 1861. He was brevetted brigadier general in November 1862. Although he saw no action with the 18th, he performed numerous staff duties efficiently and retained command of the 18th at the end of the war.

On 28 June 1866, Carrington’s column arrived at Fort Reno. Here, Carrington spent 10 days repairing, provisioning, and garrisoning the fort with a company of infantry. On 9 July, the remainder of the 2d Battalion left Fort Reno with all its impedimenta. Four days later, Carrington selected a site for the construction of his headquarters post.

Carrington’s chosen site lay just south of the point where the Bozeman Trail crossed Big Piney Creek. The large valley in which the fort sat was surrounded on three sides by high terrain. To both the north and south, the Bozeman Trail passed over ridges out of sight of the fort. To the west, the valley stretched 5 or 6 miles along Little Piney Creek before giving way to the foothills of the Bighorn Mountains. It was up this valley that the woodcutters and log teams would have to travel to provide the all-important building materials and fuel for the post’s cooking and heating fires. Carrington’s selection of this position has long been questioned. One weakness of the site was that the Sioux and Cheyenne continuously dominated the high ground and observed all movement into and around the fort.

Construction of Fort Phil Kearny began as soon as Carrington’s column arrived and continued almost until it was abandoned. The main post was an 800-foot by 600-foot stockade made by butting together 11-foot-high side-hewn pine logs in a trench 3 feet deep. The stockade enclosed barracks and living quarters for the troops, officers, and most of their families; mess and hospital facilities; the magazine; and a variety of other structures. An unstockaded area encompassing shops, stables, and the hay corral extended another 700 feet from the south palisade to Little Piney Creek, the primary water source for the fort. Two primary entrances provided access for wagons to the post, the main gate on the east wall and a sally port on the west side of the unstockaded area.

In July, Carrington detached two companies under Captain Nathaniel C. Kenney to move even farther up the Bozeman Trail to build a third fort, Fort C. F. Smith, 91 miles north of Fort Phil Kearny near present-day Yellowtail, Montana. The Army also established two additional forts along the trail in 1867: Fort Fetterman near the trail’s starting point and Fort Ellis on the west side of Bozeman Pass.

Fort Phil Kearny Besieged

Red Cloud, an influential Oglala Sioux chief, was strongly opposed to the US Army’s efforts to build forts along the Bozeman Trail. He had become convinced by episodes such as the Grattan Affair and Brigadier Harney’s retaliation that his Oglala Sioux could no longer live in the Platte River Region near Fort Laramie. Therefore, in the late 1850’s, the Oglala Sioux pushed west into the Powder River country hoping to stay away from the continuing US migration. He saw the Powder River country as his people’s last refuge from the encroaching whites.

Almost as soon as Carrington began construction on his Bozeman Trail forts, hostilities commenced between the Army and the Sioux. Carrington concentrated all his limited resources on building Fort Phil Kearny. He applied little emphasis on training or offensive operations and only reacted to Indian raids with ineffectual pursuits. On the other hand, Red Cloud concentrated most of his efforts on sporadic harassments against Fort Phil Kearny and traffic along the Bozeman Trail. His warriors became very adept at stealing livestock and threatening the woodcutting parties. The Sioux avoided all unnecessary risk and easily avoided most Army attempts at pursuit, which demoralized the soldiers because of their inability to bring the Indians to battle. Red Cloud’s warriors also presented a constant threat of attack along the Bozeman Trail. The forts’ garrisons barely had the resources to protect themselves, so emigrant travel along the trail all but ceased. In essence, the trail became a military road, and most of the traffic was limited to military traffic bringing in supplies. Red Cloud’s strategy of a distant siege had negated the shortcut to the Montana gold fields.

In November, Carrington received a small number of reinforcements. They included: Captain (Brevet Lieutenant Colonel) William J. Fetterman and Captain (Brevet Major) James Powell-both experienced combat veterans of the Civil War. The very aggressive Fetterman quickly joined with other frustrated officers to push Carrington for offensive action against the Indians. Unfortunately, like most of his fellow officers at the fort, he had no experience in Indian warfare.

In December 1866, the Indians were encouraged by their success in harassing the forts and decided to attempt to lure an Army detachment into an ambush. During that same time period, having completed essential work on the fort, Carrington decided to initiate offensive operations. Carrington planned to counter the next raid with his own two-pronged attack. He instructed Captain Fetterman to pursue the raiders and push them down Peno Creek. Carrington would then take a second group of soldiers over Lodge Trail Ridge and cut off the withdrawing warriors. On 6 December 1866, the Indians attacked the wood train and Carrington executed his planned counterattack. In the fight, Lieutenants Bingham and Grummond disobeyed orders and pursued Indian decoy parties into an ambush that resulted in the death of Bingham and one noncommissioned officer. Only stern discipline and timely action taken by Captain Fetterman who advanced toward the sounds of the guns prevented a larger tragedy on that day.

The 6 December skirmish influenced Carrington to suspend his plans for offensive actions and to concentrate on training instead. Conversely, the Sioux were encouraged by their success and continued to refine their ambush strategy. On 19 December, they made another attempt to lure an Army detachment into an ambush with an attack on the wood train. Captain Powell led the relief force and prudently declined to pursue the raiders. The Sioux quickly planned their next attack for 21 December.

The Fetterman Fight: The Approach

Friday morning, 21 December 1866, dawned cold and gray around Fort Phil Kearny. The temperature hovered below freezing, and snow blanketed the valleys, pine woods, and ridges in the foothills of the Bighorn Mountains. At about 1000, Colonel Carrington ordered the wood train to proceed to the pinery for the daily woodcutting detail. Knowing that an attack on the wood train was likely, he sent an especially strong escort with the wagons. Within an hour, the lookout on Pilot Knob signaled that the wood train was under attack, and firing could be heard at the fort. As he had done on similar occasions, Carrington immediately ordered a column to relieve the besieged detail. Captain Powell had successfully carried out a similar mission just 2 days earlier. But that morning, Captain Fetterman insisted on commanding the relief column.

There is considerable controversy about Carrington’s orders to Fetterman. Most secondary sources agree that Carrington told him to relieve the wood train and then return to the fort. Under no circumstances was he to go beyond Lodge Trail Ridge. On the other hand, there is no contemporary evidence that Carrington ever gave the controversial order not to go beyond Lodge Trail Ridge. It is possible that Carrington’s consent to Fetterman’s request to lead the large relief force was another preplanned offensive movement designed to catch the wood train raiders as they withdrew into the Peno Creek drainage. The story of the order may be a post–battle fabrication intended to focus the blame for the tragedy on disobedience of orders instead of the failure of a planned offensive movement against the Indians.

At 1115, Fetterman moved out of the southwestern sally port of the fort with 49 handpicked men from 4 companies of the 18th Infantry Regiment armed with muzzleloading Springfields (A Company: 21, C Company: 9, E Company: 6, and H Company: 13). A small number of the infantry, possibly the 13 men with H Company, may have been mounted. A few minutes later, Lieutenant George Grummond followed Fetterman with 27 mounted troops from the 2d Cavalry Regiment, mostly armed with Spencer repeating rifles taken from the regimental band. Captain Frederick Brown, a close friend of Fetterman, volunteered to join the column. James Wheatley and Isaac Fisher, two civilians armed with repeating rifles, also volunteered to go. Although Fetterman probably never uttered the phrase attached to his legacy, “With 80 men I could ride through the entire Sioux nation,” he was, like most other Army officers, contemptuous of his Indian foes. Nevertheless, Fetterman did embark with 80 men.

Fetterman’s route is also controversial. However, it is probable that he led his force directly north, passing to the east of Sullivant Hill before crossing the creek and ascending Lodge Trail Ridge. Fetterman’s infantry most likely paralleled the road with the cavalry along the slopes on each side as flankers. Whether or not the order not to cross the ridge was factual, it was clear to all those watching from the fort that Fetterman’s movement would take him over Lodge Trail Ridge.