It was the Phoenicians of the Lebanon coast who literally raised galleys to a new level. These seagoing Canaanites invented the trireme, though exactly when no Greek could say. Enlarging their ships, the Phoenician shipwrights provided enough height and space to fit three tiers of rowers within the hull. Their motives had nothing to do with naval battles, for such engagements were still unknown. The Phoenicians needed bigger ships for exploration, commerce, and colonization. In the course of their epic voyages, Phoenician seafarers founded great cities from Carthage to Cádiz, made a three-year circumnavigation of Africa (the first in history) in triremes, and spread throughout the Mediterranean the most precious of their possessions: the alphabet.

The first Greeks to build triremes were the Corinthians. From their city near the Isthmus of Corinth these maritime pioneers dominated the western seaways and could haul their galleys across the narrow neck of the Isthmus for voyages eastward as well. The new Greek trireme differed from the Phoenician original in providing a rowing frame for the top tier of oarsmen, rather than having all the rowers enclosed within the ship’s hull. Some triremes maintained the open form of their small and nimble ancestors, the triakontors and pentekontors. Others had wooden decks above the rowers to carry colonists or mercenary troops. Greek soldiers of fortune, the “bronze men” called hoplites, were in demand with native rulers from the Nile delta to the Pillars of Heracles.

Like the Phoenician cities of Tyre and Sidon, Corinth was both a great center of commerce and a starting point for large-scale colonizing missions. Triremes could greatly improve the prospects of colonizing ventures, being able to carry more of the goods that new cities needed: livestock and fruit trees; equipment for farms and mills and fortifications; household items and personal belongings. For defense against attack during their voyages through hostile waters, or against opposition as the colonists tried to land, the large crew and towering hull made the trireme almost a floating fortress.

The earliest known naval battle among Greek fleets was a contest between the Corinthians and their own aggressively independent colonists, the Corcyraeans. Though the battle took place long after the Corinthians began building triremes, it was a clumsy collision between two fleets of pentekontors. The outcome was entirely decided by combat between the fighting men on board the ships. Naval maneuvers were nonexistent. This primitive procedure would typify all Greek sea battles for the next century and a half.

Then, at about the time of Themistocles’ birth, two landmark battles at opposite ends of the Greek world brought about a seismic shift in naval warfare. First, in a battle near the Corsican town of Alalia, sixty Greek galleys defeated a fleet of Etruscans and Carthaginians twice their own size. How was this miracle achieved? The Greeks relied on their ships’ rams and the skill of their steersmen rather than on man-to-man combat. Shortly afterward, at Samos in the eastern Aegean, a force of rebels in forty trireme transports turned against the local tyrant and crushed his war fleet of one hundred pentekontors. In both battles victory went to a heavily outnumbered fleet whose commanders made use of innovations in tactics or equipment. Ramming maneuvers and triremes thus made their debut in the line of battle almost simultaneously. Together they were to dominate Greek naval warfare for the next two hundred years.

Now everyone wanted triremes, not just as transports but as battleships. Rulers of Greek cities in Sicily and Italy equipped themselves with triremes. In Persia the Great King commanded his maritime subjects from Egypt to the Black Sea to build and maintain trireme fleets for the royal levies. The core of Persian naval power was the Phoenician fleet, but the conquered Greeks of Asia Minor and the islands were also bound by the king’s decree. All these forces could be mustered on demand to form the huge navy of the Persian Empire. Themistocles believed that Athens’ new trireme fleet might soon face not only the islanders of Aegina but the armada of the Great King as well.

While many cities and empires jostled for the prize of sea rule, ultimate success in naval warfare called for sacrifices that few were willing or able to make. Only the most determined of maritime nations would commit the formidable amounts of wealth and hard work that the cause required, not just for occasional emergencies but over the long haul. With triremes the scale and financial risks of naval warfare escalated dramatically. These great ships consumed far more materials and manpower than smaller galleys. Now money became, more than ever before, the true sinews of war.

Even more daunting than the monetary costs were the unprecedented demands on human effort. The Phocaean Greeks who won the historic battle at Alalia in Corsica understood the need for hard training at sea, day after exhausting day. In the new naval warfare, victory belonged to those with the best-drilled and best-disciplined crews, not those with the most courageous fighting men. Skillful steering, timing, and oarsmanship, attainable only through long and arduous practice, were the new keys to success. Ramming maneuvers changed the world by making the lower-class steersmen, subordinate officers, and rowers more important than the propertied hoplite soldiers. After all, a marine’s spear thrust might at best eliminate one enemy combatant. A trireme’s ramming stroke could destroy a ship and its entire company at one blow.

Themistocles had specified that Athens’ new ships should be fast triremes: light, open, and undecked for maximum speed and maneuverability. Only gangways would connect the steersman’s small afterdeck to the foredeck at the prow where the lookout, marines, and archers were stationed. The new Athenian triremes were designed for ramming attacks, not for carrying large contingents of troops. By committing themselves completely to this design, Themistocles and his fellow Athenians were taking a calculated risk. For many actions, fully decked triremes were more serviceable. Time would tell whether the city had made the right choice.

The construction of a single trireme was a major undertaking: building one hundred at once was a labor fit for Heracles. Once the rich citizens who would oversee the task received their talents of silver, each had to find an experienced shipwright. No plans, drawings, models, or manuals guided the builder of a ship. A trireme, whether fast or fully decked, existed at first only as an ideal image in the mind of a master shipwright. To build his trireme, the shipwright required a wide array of raw materials. Most could be supplied locally from the woods, fields, mines, and quarries of Attica itself. Many local trades and crafts would also take part in building the new fleet.

First, timber. The hills of Attica rang with the bite of iron on wood as the tall trees toppled and crashed to the ground: oak for strength; pine and fir for resilience; ash, mulberry, and elm for tight grain and hardness. After woodsmen lopped the branches from the fallen monarchs, teamsters with oxen and mules dragged the logs down to the shore. The shipwright prepared the building site by planting a line of wooden stocks in the sand and carefully leveling their tops. On the stocks he laid the keel. This was the ship’s backbone, an immense squared beam of oak heartwood measuring seventy feet or more in length. Ideally this oak keel was free not only of cracks but even of knots. On its strength depended the life of the trireme in the shocks of storm and battle. Oak was chosen for its ability to withstand the routine stresses of hauling the ship onto shore and then launching it again. Once the keel was on the stocks, two stout timbers were joined to its ends to define the ship’s profile. The curving sternpost rose as gracefully as the neck of a swan or the upturned tail of a dolphin. Forward, the upright stempost was set up a little distance from keel’s end. The short section of the keel that extended forward of the stempost would form the core of the ship’s beak and ultimately support the bronze ram.

Between the stern- and stemposts ran the long lines of planking. In triremes the outer shell was built up by joining plank to plank, rather than by attaching planks to a skeleton of frames and ribs as in later “frame-first” traditions. For the ancient “shell-first” construction the builders set up scaffolds on either side of the keel to support the planking as the ship took shape. They cut the planks with iron saws or adzes. Because the smooth lengths of pine were still green from the tree, it was easy to bend them to shape. Along the narrow edges of each plank the builders bored rows of holes: tiny ones for the linen cords, larger ones for the gomphoi or pegs. The latter were wooden dowels about the size of a man’s finger that acted as tenons. Starting on either side of the keel, the shipwright’s assistants secured the rows of planks by matching the row of larger holes to the tops of the pegs projecting from the plank below, then tapping the new plank into place with mallets. The pegs, now invisible, would act as miniature ribs to support and stiffen the hull. No iron nails or rivets were used in a trireme.

Once the planks were in place, the shipwright’s assistants spent days squatting on the inside of the rising hull, laboriously threading linen cords through the small holes along the planks’ edges and pulling them tight. Greek farmers sowed linon or flax in autumn, tended and weeded the fields over the winter, and harvested the crop in spring when the blue flowers had faded. The stems were cut, soaked, and allowed to rot. After beating and shredding, lustrous white fibers emerged from the decayed husk and pith. Twisting these fibers into thread produced a substance with near-miraculous properties. Linen cloth and padding were impenetrable enough to serve in protective vests or body armor for hoplites on land and for marines on board ship, while a net of linen cords could hold a tuna or a wild boar. Yet linen could be spun so fine that one pound might yield several miles of thread. Unlike wool it would not stretch or give with the working of the ship at sea. Linen also possessed the very proper nautical quality of being stronger wet than dry.

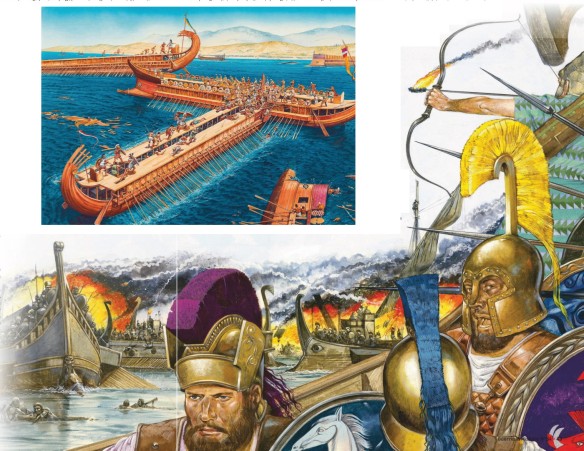

Battle of Salamis

The Battle of Salamis was the most important naval engagement of the Greco- Persian Wars. When news came of the Greek defeat at Thermopylae, the remaining Greek triremes sailed south to Salamis to provide security for the city of Athens. With no barrier remaining between Athens and the Persian land force, the proclamation was made that every Athenian should save his family as best he could. Some citizens fled to Salamis or the Peloponnese, and some men joined the crews of the returning triremes. When Xerxes and his army arrived at Athens the city was devoid of civilians, although some troops remained to stage a defense (largely symbolic) of the Acropolis. The Persians soon secured it and destroyed it by fire.

Xerxes now had to contend with the remaining Greek ships. He would have to destroy them or at least leave a sufficiently large force to contain Themistocles’ ships before he could force the Peloponnese and end the Greek campaign. Everything suggested the former, for if Xerxes left the Greek force behind, his ships remained vulnerable to a flanking attack. On August 29 the Persian fleet of perhaps 500 ships appeared off Phaleron Bay, east of the Salamis Channel, and entered the Bay of Salamis.

The Greeks had added the reserve fleet at Salamis. Triremes from other states joined, giving them about 100 additional ships. The combined fleet at Salamis was thus actually larger than it had been at Artemisim: about 310 ships.

Xerxes and his admirals did not wish to fight the Greek fleet in the narrow waters of the Salamis Channel, and for about two weeks the Persians busied themselves constructing causeways across the channel so that they might take the island without having to engage the Greek ships. Salamis then contained most of the remaining Athenian population and government officials, and the Persians reasoned that their capture would bring the fleet’s surrender. Massed Greek archers, however, gave the workers such trouble that the Persians abandoned the effort.

On September 16 or 17 Xerxes met with his generals and chief advisers at Phalerum. Herodotus tells us that all except Queen Artemisia of Halicarnassus, the commander of its squadron in the Persian fleet, favored engaging the Greek fleet in a pitched battle. Xerxes then brought advance elements of his fleet from Phalerum, off Salamis. He also put part of his vast army in motion toward the Peloponnese in the hope that this action would cause the Greeks of that region to order their ships from the main Greek fleet to return home, allowing him to destroy them at his leisure. Failing that, Xerxes sought a battle in the open waters of the Saronic Gulf (Gulf of Aegina) that forms part of the Aegean Sea. There his superior numbers would have the advantage.

Themistocles wanted a battle in the Bay of Salamis. Drawing on the lessons of the Battle of Artemisium, he pointed out that a fight in close conditions would be to the advantage of the better-disciplined Greeks. With his captains in an uproar at this and with the likely possibility that the Peloponnesian ships would bolt from the coalition, Themistocles resorted to one of the most famous stratagems in all military history. Before dawn on September 19 he sent a trusted slave, an Asiatic Greek named Sicinnus, to the Persians with a letter informing Xerxes that Themistocles had changed sides. Themistocles gave no reason for this decision but said that he now sought a Persian victory. The Greeks, he said, were bitterly divided and would offer little resistance; indeed, there would be pro-Persian factions fighting the remainder. Furthermore, Themistocles claimed, elements of the fleet intended to sail away during the next night and link up with Greek land forces defending the Peloponnese. The Persians could prevent this only by not letting the Greeks escape. This letter contained much truth and was, after all, what Xerxes wanted to hear. It did not tell Xerxes what Themistocles wanted him to do: engage the Greek ships in the narrows.

Xerxes, not wishing to lose the opportunity, acted swiftly. He ordered Persian squadrons patrolling off Salamis to block all possible Greek escape routes while the main fleet came into position that night. The Persians held their stations all night waiting for the Greek breakout. Themistocles was counting on Xerxes’ vanity. As Themistocles expected, the Persian king chose not to break off the operation that he had begun.

The Greeks then stood out to meet the Persians. Xerxes, seated on a throne at the foot of nearby Mount Aegaleus on the Attic shore across from Salamis, watched the action. Early on the morning of September 20 the entire Persian fleet went on the attack, moving up the Salamis Channel in a crowded mile-wide front that precluded any organized withdrawal should that prove necessary. The details of the actual battle are obscure, but the superior tactics and seamanship of the Greeks allowed them to take the Persians in the flank. The confusion of minds, languages, and too many ships in narrow waters combined to decide the issue in favor of the Greeks.

The Persians, according to one account, lost some 200 ships, while the defenders lost only 40. However, few of the Greeks, even from the lost ships, died; they were for the most part excellent swimmers and swam to shore when their ships floundered. The Greeks feared that the Persians might renew the attack but awoke the next day to find the Persian ships gone. Xerxes had ordered them to the Hellespont to protect the bridge there.

The Battle of Salamis meant the end of the year’s campaign. Xerxes left two-thirds of his forces in garrison in central and northern Greece and marched the remainder to Sardis. A large number died of pestilence and dysentery on the way. The Greco-Persian Wars concluded a year later in the Battle of Plataea and the Battle of Mycale.

References Green, Peter. The Greco-Persian Wars. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996. Herodotus. The History of Herodotus. Edited by Manuel Komroff. Translated by George Rawlinson. New York: Tudor Publishing, 1956. Nelson, Richard B. The Battle of Salamis. London: William Luscombe, 1975. Strauss, Barry. The Battle of Salamis: The Naval Encounter That Saved Greece-and Western Civilization. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004.