Hereditary archers and menfat “shock troops” were supported by conscripts. The centre of the battle line would consist of massed close fighters in columns or deep lines, supported by massed archer formations. Archers and close combat troops formed up in separate bodies. The archers were to discharge a heavy volume of arrows in support of the close-combat troops, while themselves avoiding hand-to-hand fighting. Lighter troops such as javelinmen or tribal auxiliaries would form up on the flanks of the array. Although generals were usually bowmen, and can be so represented, their bodyguards were axemen with large shields.

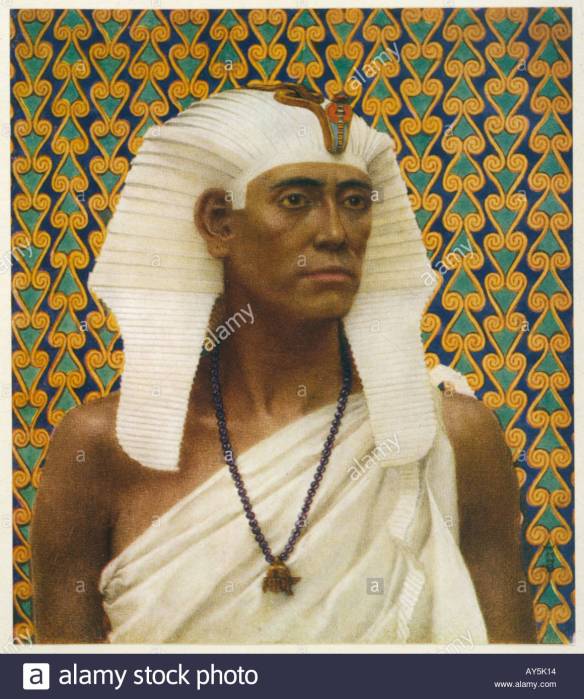

Senusret came to the throne in about 1878 BC, and is thought to have reigned for 37 years. He is probably the best known, visually, of all the Middle Kingdom pharaohs with his brooding, hooded-eyed and careworn portraits, carved mainly in hard black granite. In Middle Kingdom royal portrait sculpture there is a move away from the almost bland, godlike and complacent representations of the Old Kingdom to a more realistic likeness. Part of this stems from the realization that the king, although still a god on earth, is nevertheless concerned with the earthly welfare of his people. The Egyptians no longer placed huge emphasis and resources on erecting great monuments to the king’s immortal hereafter, as the rather inferior Middle Kingdom pyramids show. Instead, greater emphasis was placed on agricultural reforms and projects, best exemplified by the great Bahr Yusuf canal (p. 82).

Manetho describes Senusret as a great warrior, and unusually mentions that the king was of great height: ‘4 cubits 3 palms 2 fingers breadth’ – over 6 ft 6 in (2 m). His commanding presence must have helped the success of his internal reforms in Egypt. Most notably he managed to curtail the activities of the local nomarchs, whose influence had once again risen to challenge that of the monarchy, by creating a new system of government that subjugated the autonomy of the nomarchs. The king divided the country into three administrative departments – the North, the South and the Head of the South (Elephantine and Lower Nubia) – each administered by a council of senior staff which reported to a vizier.

Senusret III as military leader

With the internal stability of the country assured, Senusret III was able to concentrate on foreign policy. He initiated a series of devastating campaigns in Nubia quite early in his reign, aimed at securing Egypt’s southern borders against incursions from her bellicose neighbours and at safeguarding access to trade routes and to the mineral resources of Nubia. To facilitate the rapid and ready access of his fleets he had a bypass canal cut around the First Cataract at Aswan. A canal had existed here in the Old Kingdom, but Senusret III cleared, broadened and deepened it, repairing it again in Year 8 of his reign, according to an inscription. Senusret was forced to bring the Nubians into line on several occasions, in Years 12 and 15 of his reign, and he was clearly proud of his military prowess in subduing the recalcitrant tribes. A great stele at Semna (now in Berlin) records, ‘I carried off their women, I carried off their subjects, went forth to their wells, smote their bulls: I reaped their grain, and set fire thereto’. He pushed Egypt’s boundary further south than any of his forebears and left an admonition for future kings: ‘Now, as for every son of mine who shall maintain this boundary, which My Majesty has made, he is my son, he is born of My Majesty, the likeness of a son who is the champion of his father, who maintains the boundary of him that begat him. Now;’ as for him who shall relax it, and shall not fight for it; he is not my son, he is not born to me.’ No wonder Senusret was worshipped as a god in Nubia by later generations, or that his sons and grandsons maintained their inheritance.

Although most of Senusret’s military energies were directed against Nubia, there is also record of a campaign in Syria – but it seems to have been more one of retribution and to gain plunder than to extend the Egyptian frontiers in that direction.

Middle Kingdom Warfare

By the time of the Middle Kingdom the troops carried copper axes and swords. The long, bronze spear became standard as did body armor of leather over short kilts. The army was better organized with “a minister of war and a commander in chief of the army, or an official who worked in that capacity” (Bunson, 169). These professional troops were highly trained and there were elite “shock troops” used as the vanguard. Officers were in charge of an unspecified number of men in their units and reported to a commander who then reported up the chain of command; it is unclear exactly what the individual responsibilities were or what they were known as but military life offered a much greater opportunity at this time than in the past. Historian Marc van de Mieroop writes:

Although our knowledge of the military in the Middle Kingdom is very limited, it seems that its role in society was much greater than in the Old Kingdom. The army was well organized and in the 12th dynasty it had a core of professional soldiers. They served for prolonged periods of time and were regularly stationed abroad. The army provided an outlet for ambitious men to make careers. The bulk of the troops continued to be recruited from the populations of the provinces and participated in individual campaigns only. How many troops were involved and how long they served remains unknown.

The military of the Middle Kingdom reached its apex under the reign of the warrior-king Senusret III (c. 1878-1860 BCE) who was the model for the later legendary conqueror Sesostris made famous by Greek writers. Senusret III led his men on major campaigns in Nubia and Palestine, abolished the position of nomarch and took more direct control of the regions his soldiers came from, and secured Egypt’s borders with manned fortifications.