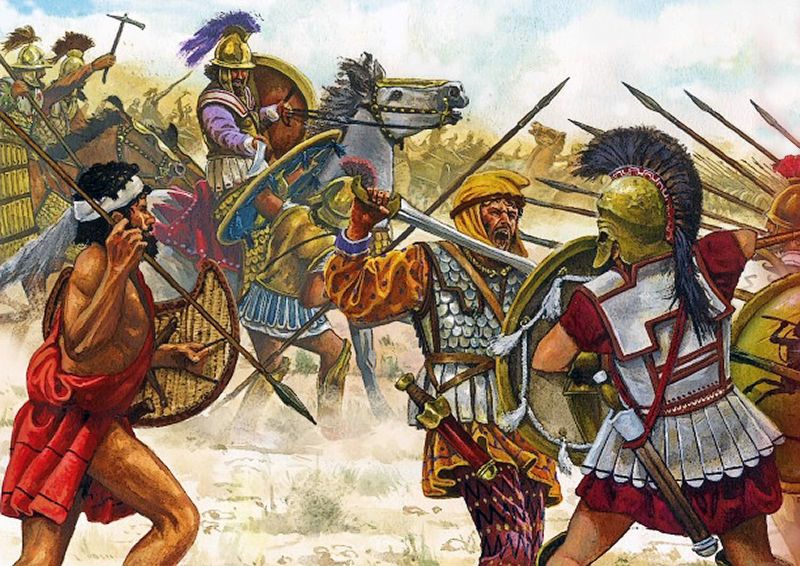

The Death of Cyrus The Younger by Peter Connolly. At the Battle of Cunaxa, Cyrus gallops on and his princely headgear falls off. One Mithridates unwittingly wounds him in the temple near his eye with a lance. Cyrus swoons and falls from his horse, then later, is speared in the leg, and in falling dashes his wounded temple against a rock and dies.

Battle of Cunaxa – First phase of battle

Battle of Cunaxa – Second phase of battle

The final year of the 5th century saw a dispute arise over succession to the Persian throne when Darius II died in 404 B. C. and his eldest son came to power as Artaxerxes II. It seems that Artaxerxes had been born prior to his father’s kingship and supporters of his brother Cyrus, who was the first male child after Darius gained the crown, challenged legitimacy of the older son’s ascension. Cyrus was summoned to the capital at Persepolis, where he faced a capital charge of treason, and it was only through intervention of Parysatis, mother of both royal claimants, that he escaped execution. Allowed to return to his satrapal post at Sardis, Cyrus was obviously aware that he remained at hazard and, if he hadn’t earlier, now began to plot a coup in earnest. He quickly called in some favors from allies in Sparta to help find mercenary hoplites and then engaged the exiled Spartan Clearchus to command them.

Clearchus created a fighting division for the Persian prince and trained it in Thrace. By the time he marched to join Cyrus, this force numbered 1,000 hoplites, 800 Thracian peltasts, 200 archers from Crete, and 40 horsemen. That these men had been collected in Europe, where Persian authorities were less likely to notice them, was typical of Cyrus’s stealthy approach to building a mercenary army. He likewise paid for upkeep of a contingent in Thessaly, giving Aristippus of Larissa money to hire 4,000 fighting men. Back in Asia Minor, Xenias (Arcadian commander of the prince’s personal bodyguard) similarly collected a large number of hoplites. These ostensibly were to combat renegade tribesmen within the satrapy; however, this was little more than a cover story that gained Cyrus another 4,000 hoplites for use in his coup attempt. Cyrus was also at this time fighting supporters of the former satrap Tissaphernes, who was leading a resistance movement in southern Ionia. The prince used this as an excuse to gather yet more mercenaries for a siege at Miletus-a combined 1,800 spearmen and 300 skirmishers under three different Greek commanders. Nor did Cyrus stop here, sending out other recruiters to engage additional soldiers from throughout the Greek world.

Naturally, Cyrus didn’t depend entirely on Greeks for his army, and he put together an even larger body of Asians. Our sources greatly exaggerate the total for this part of his host; still, their count for mounted troops appears sound at 3,000 cavalrymen and 20 scythed chariots. If we assume that Cyrus’s cavalry was about one-tenth as large as his infantry and that Greeks made up a third of the latter, then we get a figure for Asiatic infantry much like the 20,000 proposed by Anderson (1974, 99-100). Most of these lacked armor, but there must have been at least a few heavy spearmen from Lydia and Caria (most likely a myriad/baivarabam of 8,000 men at 80 percent nominal strength).

Cyrus gathered his forces during spring 401 B. C. at his satrapal capital in Lydia, but didn’t let on that his plan was to attack the Great King, saying instead that he was intent on a campaign against tribesmen in the interior. Most of his local troops were already on hand, as were a force of Grecian mercenaries that included 5,800 hoplites and 300 light foot troops that had come with Xenias and from Miletus, as well as 1,500 spearmen and 500 skirmishers under Proxenus of Thebes. Once his army was fully assembled, Cyrus marched southeast, crossing the Meander River and pausing at Colossae to gather a local Carian contingent and meet another group of Greeks. These were a portion of the men hired by Aristippus of Larissa, who was still busy in Thessaly, but had sent his friend Menon with all the troops he could spare (1,000 hoplites and half as many peltasts).

Cyrus next proceeded northeast, moving along the southern side of the Meander until reaching Celaenae. Clearchus and two other mercenary commanders joined the column here with 2,300 hoplites and 1,000 light infantry (the Spartan’s peltasts and archers). The army then continued along its northeasterly track for a while before eventually swinging south to Issos on the Cilician coast. Cyrus met a convoy of triremes at Issos that delivered the Spartan general Cheirisophus and some hoplites (700 per Xenophon, 800 according to Diodorus), who were probably neodamodeis sent in semi-official support. The mercenaries now began to question their paymaster’s actual intent. After all, they not only had many more men than needed to tackle a few tribesmen, but were also far off course for such a campaign. But Cyrus was not yet ready to reveal his plans; instead, he claimed to be marching against the satrap Abrocomas, whose realm of Phoenicia lay farther south. However, awareness of the truth must have been seeping in, as Xenias and Pasion (one of the mercenary generals who had been at Miletus) chose this moment to desert with some of their troops. Undeterred, Cyrus led on eastward toward the Euphrates River and Abrocomas.

The invading column lost 100 hoplites before it reached the Euphrates, but more than compensated by adding 400 Greek spearmen who had deserted from Abrocomas’s bodyguard. When Cyrus reached the river, which provided a path into the heart of his brother’s realm, he finally announced for the Persian throne. Persuaded by financial rewards, the Greeks agreed to join his plot. Marching along the Euphrates, they expected to meet Artaxerxes’ army at the Babylonian frontier. When this didn’t happen, Cyrus’s men relaxed a bit, but kept pushing down river. It was then, as they made a mid-morning approach to the small town of Cunaxa about 80km northwest of Babylon, that their scouts found a large royal host standing before them.

Tissaphernes had seen Cyrus’s real intent early on and warned his monarch in time to gather a powerful counterforce. Our sources tend toward gross exaggeration of Persian numbers, but reports of mounted strength at 6,000 riders and 150-200 scythed chariots seem reasonable. This suggests that the infantry probably came to around 60,000 (again, as per Anderson 1974, 100), which was nearly twice Cyrus’s strength. It’s likely that two-thirds of the king’s force were frontline troops in five 8,000-man baivaraba. Soldiers in the first three myriads derived from the old sparabara type and carried short thrusting spears and large wicker shields. There would have been one division of Persians and Medes, another of Elamites, Cissians, and Hyrkanians, and a third of elite guards from all these “Iranian” peoples. The fourth unit of the line was Egyptian and the fifth Assyrian and Chaldean/Babylonian-all spearmen with chest-to-toe shields of wood. The remaining 20,000 footmen were peltasts and archers in a variety of small contingents.

Artaxerxes had set up his host facing northwest, with Tissaphernes and a third of the cavalry (2,000 horsemen) flanking the riverbank. Light footmen stood next in line, with an Iranian unit and then the Egyptians completing Artaxerxes’ left wing. Massed at a depth of ten men across a width of just over 2.5km, the heavy infantry contingents had spearmen in the lead and half the king’s chariots a short distance farther forward. Another force of 2,000 cavalrymen held post rightward from the chariots, in position to front for their king and his elite guard in the formation center. The bodyguards stood ten deep over a span of 800m. Next right from Artaxerxes and his men were the Assyrian/Babylonian division and the last Iranian myriad in that order, together making up the royal army’s inland arm. This wing had all remaining chariots at its front and more light infantry alongside, with the final third of the cavalry pacing far right.

The sudden appearance of Artaxerxes’ army had caught Cyrus and his men strung out in line of march along the river. A third of their cavalry was in the van, followed in sequence by the Greeks, the prince and his companion horsemen, the Asiatic infantry, and Ariaeus (Cyrus’s uncle) bringing up the rear with the remaining riders. Cyrus’s men began moving up into the line of battle, but it was a long process from such a distended column. When the enemy formation finally began to advance in late afternoon, only the Greek mercenaries (flanked by their own light foot troops and cavalry, the latter next to the river) and the 600- man mounted guard under Cyrus were in place on the battlefield. And though Ariaeus and his following contingent of horsemen were coming up fast, the prince’s Asian foot troops remained hopelessly far to the rear.

Xenophon claimed that he and his countrymen waiting in phalanx came to 10,400 hoplites and 2,500 skirmishers, while the cavalry on their right was 1,000 strong. (These figures add 200 more light infantry than his various earlier tallies and 1,200 fewer spearmen. The lower hoplite number likely reflects men that left with Xenias and others posted with the baggage train, while the additional light-armed troops might have come along with Abrocomas’s bodyguard.) The Greek spearmen were able to match their enemy’s left-wing front by filing only four deep, as they had at a recent review in Cilicia. They then put their light footmen and horsemen along the river, where they were in position to match up with Tissaphernes and his cavalry. Clearchus and the troops from Thrace held the far right, with Proxenus next in line and Menon standing far left beyond all the other mercenaries. Cyrus and his guard took up center position next to the Greek left flank. But unfortunately for him, the barbarian infantry and Ariaeus’s cavalry, who should have been there to form the left wing and flank screen, were not yet in place when the battle began.

Already stretched to the practical limit, Clearchus couldn’t extend his ranks farther left and cover for Cyrus’s absent Asian troops. Likewise, any mass relocation away from the river could prove a serious liability, since it would give the enemy room to outflank his line on the right. Clearchus therefore took the only reasonable course open to him and ordered a charge directly ahead at the opposition’s left wing. His phalanx moved out on signal, a bit raggedly at first, but quickly evening up to present a fearsome image to its nervous foe across the field. The helmets, shields, and greaves of the Greeks shone golden bronze in the late afternoon sun, their gleam complimented by red tunics adopted by the mercenaries as a common uniform in imitation of Spartan custom. Clearchus’s hoplites sang war hymns and clashed spear on shield to raise a frightening din as they came on at the double. Though it has been proposed that the facing Asians at this point gave way on command to deliberately draw the Greeks away from the battle (as per Waterfield, 2006, 18), it’s much more likely and widely accepted that holding firm before the charging phalanx was simply more than the king’s men could endure. Panicking, the charioteers broke first, some abandoning their vehicles and others turning back against their own troops; the infantry then quickly followed suit, making a pellmell run for the rear before Clearchus and his men could even reach them. The Greeks gave chase with a care to keeping good order.

Tissaphernes seems to have been alone in keeping his wits about him on the royalist left, matching the Greek assault with a mounted thrust of his own. This drive along the riverside scattered the opposition horsemen and carried beyond the skirmishers on that flank. The Greek peltasts loosed a telling shower of javelins at the Persians as they swept past, and Tissaphernes, stung by this fire, decided not to turn back and fight. Instead, he led his men on to the northwest in an attack on the enemy baggage train. Cyrus, meanwhile, had held firm in the center with his guard cavalry, waiting for Ariaeus to come up with the left wing as the mercenaries carried out their successful foray on the right. However, Ariaeus and his horsemen were only just now approaching, while the Asiatic infantry was nowhere to be seen. The Greeks thus left Cyrus and his small command terribly exposed when they took up their pursuit. On the other side, those holding the king’s right wing prepared to take advantage by swinging around and wrapping across a still naked enemy left flank. At least a portion of the royal chariots and cavalry on that side of the field went into action at the same time, engaging to turn back Cyrus’s mounted rear guard before it could reach his side.

Cyrus could have retreated at this point in hopes of fighting another day on better terms. Yet such a move would have been fraught with political risk, appearing timid and costing him the trust and loyalty of many supporters. Moreover, it seems to have been contrary to this young man’s proud and aggressive temperament. He therefore elected to make a risky, high-profile charge into the enemy center, seeking to find and kill his brother in personal combat. Our ancient sources have painted what followed in highly romantic terms, with Cyrus cutting through the opposing cavalry screen to wound his rival only to be unhorsed by a blow to the head and killed once on the ground. Regardless of whether such colorful details are accurate, the daring pretender lost his life in the fight, as did most of his closest companions. This effectively put an end to the rebellion, even though the battle of Cunaxa had yet to run its full course.

With Cyrus slain, Artaxerxes pushed on to join up with Tissaphernes. His men then pillaged most of Cyrus’s supply train, though a small guard of hoplites managed to protect a modest portion. Eventually, the Great King reordered his troops and turned back south so that he could deal with the still intact division of Greek mercenaries. Clearchus and his men had by this time learned of the assault on their baggage and that the king’s men were forming up in their rear. They quickly executed a countermarch, a parade-ground maneuver that changed their facing 180 degrees by opening ranks so that each man could pivot about face, thus inverting file order and placing the men previously on the right wing now on the left. Men at the front of the reversed files then held fast as those behind followed their original file leaders forward to resume their initial front-to-back order (though the wings remained exchanged).

As the armies again closed, the Persians swung away from the Euphrates to skirt eastward across the right side of the Greek formation. Fearing an attack on his unshielded flank, Clearchus again skillfully maneuvered his phalanx, this time rotating each man 90 degrees to turn line into column. He next marched in a right turn until this column was fully deployed on a southward facing and then pivoted his troops 90 degrees left, putting them back into line of battle with the river at their back and enemy in front. As before, the Greeks chorused battle songs and advanced with intent to engage in shock combat. And once more, their foes gave way before contact was made, collapse coming at an even great distance of separation than in the opening bout.

The victorious mercenaries chased after the Persians, but came to a halt before a rise that hid what lay ahead and took the precaution of scouting the far side for an ambush. By the time that they had precluded a trap, the sun was dropping below the horizon, which prompted them to call off further pursuit. The Greeks fell back to set up a trophy and returned to their ravaged camp. Though Clearchus had gained two essentially bloodless tactical victories on the day, he didn’t know what had transpired elsewhere on the field. Indeed, the news that Cyrus was dead and the rest of his army (under a wounded Ariaeus) had withdrawn didn’t arrive until dawn, just as he and the other Greeks were gathering for a fresh offensive against the king’s host.

Artaxerxes had no desire to fight again, the succession dispute having already been resolved. Instead, he entered into an agreement to let Clearchus and his men join Ariaeus in a peaceful march back to Ionia. This, however, proved to be a ruse, as his general Tissaphernes followed with an army and successfully intrigued to separate Ariaeus and his Asiatic troops from their Greek allies. Tissaphernes then tricked Clearchus and most of the other mercenary commanders into attending a conference at his camp, where he seized them for delivery to the king and eventual execution. At the same time, the Persians also cut down some lesser Greek officers and 200 hoplites that had come along with their generals in hope of securing supplies. Only one badly wounded man got away from this slaughter, staggering back to report the treachery.

Having lost most of their leaders, the mercenaries briefly gave way to despair, yet soon recovered to select another set of commanders. Chief among these was the Spartan general Cheirisophus. Steeped in Greece’s most respected martial tradition and with a long record of senior service, Cheirisophus’s election was no surprise. However, the fresh list of officers also included Xenophon, an Athenian with no prior experience of military command. He had come along as a friend of Proxenus of Thebes (who had been among those captured) and it was his ability to remain calm and eloquently dispense sensible advice that earned him a command slot. Fortunately for his companions, this untested young man’s soldierly skills would soon prove up to the challenge.