Just as Africans were taking their first, tentative steps towards nationhood and independence, Spain and Italy launched what turned out to be the last large-scale wars of conquest on the continent, in Morocco and Abyssinia. Both nations were driven by greed and historic grievances which alleged that their legitimate imperial ambitions had been frustrated or overlooked by the great powers. Jealousy and bruised pride were most strongly felt by right-wing politicians, professional soldiers, moneymen and journalists who lobbied for imperial expansion, promising that it would yield prestige and profit. In Italy, aggressive imperialism and an infatuation with the glories of the Roman Empire were central to the ideology of Mussolini’s Fascist Party which snatched power in 1922. Like Spain, Italy was a relatively poor country with limited capital reserves and industrial resources, deficiencies that were ignored or glossed over by imperial enthusiasts who argued that in the long term imperial wars would pay for themselves.

In 1900 Spain was a nation in eclipse. Over the past hundred years it had been occupied by Napoleon and endured periodic civil wars over the royal succession; it entered the twentieth century riven by violent social and political tensions. Spain’s infirmity was brutally exposed in 1898, when she was defeated by the United States in a short war that ended with the loss of Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines, all that remained of her vast sixteenth-century empire.

National shame was most deeply felt in the upper reaches of a hierarchical society where the conviction took root that Spain could only redeem and regenerate itself by a colonial venture in Morocco. Support for this enterprise was most passionate among the numerous officers of the Spanish army (there was one for every forty-seven soldiers), who found allies in King Alfonso XIII, the profoundly superstitious and obscurantist Catholic Church and conservatives in the middle and landowning classes. The army had its own newspaper, El Ejército Español, which proclaimed that empire was the ‘birthright’ of all Spaniards, and predicted that ‘weapons’ would ‘plough the virgin soil so that agriculture, industry, and mining might flourish’ in Morocco.

Morocco was Spain’s new El Dorado. In 1904 Spain and France secretly agreed to share Morocco, with the French coming off best with the most fertile regions. Spain’s portion was the littoral of the Mediterranean coast and the inaccessible Atlas Mountains of the Rif, home to the fiercely independent Berbers. The war began in 1909 and jubilant officers, including the young Francisco Franco, looked forward to medals and promotion, while investors touted for mining and agricultural concessions. Optimism dissolved on the battlefield and, within a year, the Spanish army found itself bogged down in a guerrilla war, just as it had in Cuba forty years before. Reinforcements were hastily summoned, but in July 1909 the mobilisation of reservists triggered a popular uprising among the workers of Barcelona. Breadwinners and their families wanted no part in the Moroccan adventure, and henceforward all left-wing parties opposed a war that offered the workers nothing but conscription and death. Resentful draftees had to be stiffened by Moroccan levies (Regulares) and, in 1921, the sinister Spanish Foreign Legion (Tercio de Extranjeros), a band of mostly Spanish desperadoes whose motto was ‘Viva la Muerte!’ These hirelings once appeared at a ceremonial public parade with Berber heads, ears and arms spiked on their bayonets.

Resistance was strongest among the Berbers of the Atlas, who not only defended their mountainous homeland but created their own state, the Rif Republic, in September 1921. Its founder and guiding spirit was a charismatic visionary, Abd el-Krim, a jurist who had once worked for the Spanish, but believed that the future freedom, happiness and prosperity of the Berbers could only be achieved by the creation of a modern, independent nation. It had its own flag, issued banknotes and, under el-Krim’s direction, was embarking on a programme of social and economic regeneration which included efforts to eliminate slavery. The Riffian army was well suited to a partisan war. Its soldiers were chiefly horsemen armed with up-to-date rifles, supported by machineguns and modern artillery. The Riffians also had good luck, for they were pitched against an army with tenuous lines of communications and led by fumbling generals.

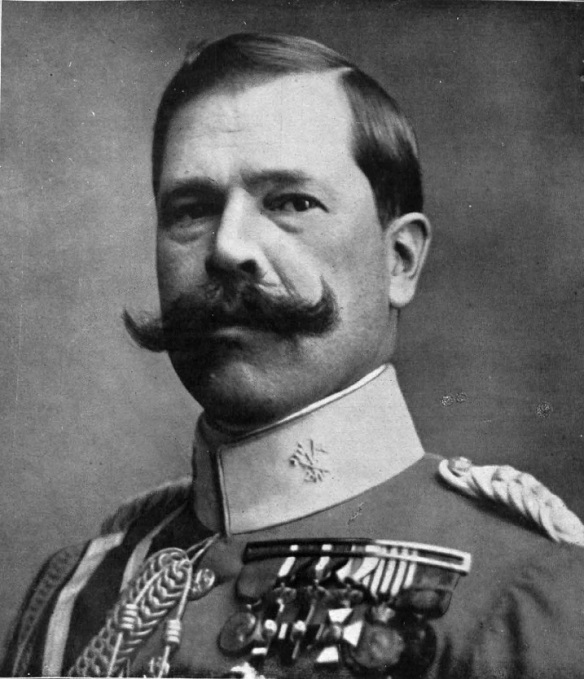

General Manuel Fernandez Silvestre y Pantiga

Riffian superiority in the battlefield was spectacularly proved in July 1921, when Spain launched an offensive with 13,000 men designed to penetrate the Atlas foothills and secure a decisive victory. What followed was the most catastrophic defeat ever suffered by a European army in Africa, the Battle of Annual. The Spanish were outmanoeuvred, trapped and trounced with a loss of over 10,000 men in the fighting and ensuing rout. Officers fled in cars, the wounded were abandoned and tortured, and their commander, General Manuel Fernandez Silvestre y Pantiga, shot himself. The circumstances of his death were ironic, insofar as his manly bearing and extended, bushy and painstakingly groomed moustache so closely fitted the European stereotype of the victorious imperial hero. A post-mortem on the Annual debacle revealed Silvestre’s reckless over-confidence, his obsequious desire to satisfy King Alfonso XIII’s wish for a quick victory, ramshackle logistics, a precipitate collapse of morale and the mass desertions of Moroccan Regulares.

Spain responded with more botched offensives, but now the deficiencies of its commanders were offset by the latest military technology. Phosgene and mustard gas bombs dropped from aircraft would bring the Riffians to their knees. This tactic was strongly urged by Alfonso XIII, a Bourbon with all the mental limitations and prejudices of his ancestors. Together, his generals persuaded him that, if unchecked, the Republic of the Rif would trigger ‘a general uprising of the Muslim world at the instigation of Moscow and international Jewry’. Spain was now fighting to save Christian civilisation, just as it had done in the Middle Ages when its armies had driven the Moors from the Iberian peninsula.

The technology for what are now called weapons of mass destruction had to be imported. German scientists supervised the manufacture of the poison gas at two factories, one of which, near Madrid, was named ‘The Alfonso XIII Factory’. Over 100 bombers were purchased from British and French manufacturers, including the massive Farman F.60 Goliath. By November 1923 the preparations had been completed, and one general hoped that the gas offensive would exterminate the Rif tribesmen.

Between 1923 and 1925 the Spanish air force pounded Rif towns and villages with 13,000 bombs filled with phosgene and mustard gas as well as conventional high explosives. Victims suffered sores, boils, blindness and the burning of skin and lungs, livestock were killed and crops and vegetation withered. Residual contamination persisted and was a source of stomach and throat cancers and genetic damage.4 Details of these atrocities remained hidden for seventy years, and in 2007 the Spanish parliament refused to acknowledge them or consider compensation. The Moroccan government disregarded the revelations, for fear that they might add to the grievances of the discontented Berber minority.

Conventional rather than chemical weapons brought down the Rif Republic. Worrying signs that Spain’s war in the Rif might destabilise French Morocco drew France into the conflict in 1925. Over 100,000 French troops, tanks and aircraft were deployed alongside 80,000 Spaniards, and the outnumbered Riffian forces were broken. Newsreel cameramen (a novelty on colonial battlefields) filmed the captive Abd el-Krim as he began the first stage of his journey to exile in Réunion in the Indian Ocean. He was transferred to France in 1947 and was later moved to Cairo where he died in 1963, a revered elder statesman of North African nationalism.

#

Spain had gained a colony and, unwittingly, a Frankenstein’s monster, the Army of Africa (Cuerpo de Ejército Marroquí). Its cadre of devout, reactionary officers assumed the role of the defenders of traditionalism in a country beset by political turbulence after the abdication of Alfonso in 1931. Politicians of the Right saw the Africanistas (as the officer corps was called) as ideological accomplices in their struggle to contain the trade unions, Socialists, Communists and Anarchists. The Moroccan garrison became a praetorian guard that could be unleashed on the working classes if they ever got out of hand. They did, in October 1934, when the miners’ strike in the Asturias aroused fears of an imminent Red revolution. It was forestalled by application of the terror that had recently been used to subdue Spanish Morocco. Aircraft bombed centres of disaffection and the Foreign Legion and Moroccan troops were summoned to restore order and storm the strikers’ stronghold at Oviedo. Its capture and subsequent mopping-up operations were marked by looting, rape and summary executions by the Legionaries and Regulares. Franco (now a general) presided over the terror. Like his fellow Africanistas, he believed that it was their sacred duty to rescue the old Spain of landowners, priests and the passive and obedient masses from the depredation of godless Communists and Anarchists.

Red revolution seemed to come closer on New Year’s Day 1936 with the emergence of a coalition government which called itself the ‘Popular Front’. It was confirmed in power by a narrow margin in a general election soon afterwards, and the far Left began clamouring for radical reform and wage rises. Strikes, assassinations and violent demonstrations proliferated during the spring and early summer, the Right trembled, acquired arms and covertly sounded out the Africanista generals. Together they contrived a coup whose success depended on the 40,000 soldiers of the Moroccan garrison who made up two-fifths of the Spanish army.

On 17 July 1936 Africa, in the form of Legionary and Regulares units from Morocco, invaded Spain. They were the spearhead of the Nationalist uprising and were soon reinforced by contingents flown across the Mediterranean in aircraft supplied by Hitler. Combined with local anti-Republican troops and right-wing volunteers, the African army quickly secured a power base across much of south-western and northern Spain. From the start, the Nationalists used their African troops to terrorise the Republicans. Speaking on Radio Seville, General Gonzalo Queipo de Llano warned his countrymen and women of the promiscuity and sexual prowess of his Moroccan soldiers who, he assured listeners, had already been promised their pick of the women of Madrid.

The colonial troops fulfilled his expectations. There were mass rapes everywhere by Legionaries and Regulares, who also massacred Republican civilians. Later, George Orwell noticed that Moroccan soldiers enjoyed beating up fellow International Brigade prisoners of war, but desisted once their victims uttered exaggerated howls of pain. One wonders whether their brutality was the result of their suppressed loathing of all white men rather than any attachment to Fascism or the Spain of the hidalgo and the cleric. Muslim religious leaders in Morocco had backed the uprising, which was sold to them as a war against atheism. As the Regulares marched into Seville they were given Sacred Heart talismans by pious women, which must have been bewildering.

When the Republicans were finally defeated in the spring of 1939, there were 50,000 Moroccans and 9,000 Legionaries fighting in the Nationalist army along with German and Italian contingents. Although necessity compelled him to concentrate his energies on national reconstruction, Franco, now dictator of Spain, harboured imperial ambitions. The fall of France in June 1940 offered rich pickings and he immediately occupied French Tangier. Shortly afterwards, when he met Hitler, Franco named his price for cooperation with Germany as French Morocco, Oran and, of course, Gibraltar. The Führer was peeved by his temerity and prevaricated. Fascist Spain remained a malevolent neutral; early in 1941 the tiny Spanish coastal colonies of Guinea and Fernando Po were sources of anti-British propaganda and bases for German agents in West Africa.7 Spanish anti-Communist volunteers joined Nazi forces in Russia.

#

Franco’s demands had been modest compared to those made by Mussolini, for whom the French surrender was a heaven-sent opportunity to implement his long-term plans for a vast Italian empire in Africa. In 1940 he asked the Germans for Corsica, Tunisia, Djibuti and naval bases at Toulon, Ajaccio and Mers-el-Kebir on the Algerian coast, and he was planning to invade the Sudan and British Somaliland. Mussolini’s flights of fancy extended to the annexation of Kenya, Egypt and even, in their giddier moments, Nigeria and Liberia.8 Hitler’s response was frosty, for at that time his Foreign Ministry was preparing a blueprint ‘to rationalise colonial development for the benefit of Europe’. An enlarged Italian empire was not part of this plan.

Fascism had always been about conquest. As a young misfit spitefully living on the margins of society, Mussolini had convinced himself that ‘only blood could turn the bloodstained wheels of history’. This remained his creed: violence was a valid and desirable means for a government to gets its own way at home and abroad. ‘I don’t give a damn!’ was the slogan of Mussolini’s Blackshirt hoodlums, and he applauded it as ‘evidence of a fighting spirit which accepts all the risks’. Violence was essential for Italy to attain both its rightful place in the world and the territorial empire that would uphold its pretensions. Yet Mussolini’s projected empire was not just about accumulating power: he promised that it would, like its Roman predecessor, bring enlightenment to its subjects. Italians were fitted for this noble task for, as the Duce insisted, ‘It is our spirit that has put our civilisation on the by-ways of the world.’

Cinema informed the masses of the ideals and achievements of the new Rome. A propaganda short of 1937 entitled Scipione l’Africano blended past and present glories. There was footage of Mussolini’s recent visit to Libya, where he is seen watching a spectacular enactment of Scipio’s victory over Carthage with elephants and Italian soldiers dressed as Roman legionaries. It was followed by scenes of a mock Roman triumph alternated with shots of the new Caesar, Mussolini, inspecting his troops. There are also images of babies and mothers surrounded by children as a reminder of the Duce’s campaign to raise the birth rate, which would, among other things, provide a million colonists for an enlarged African empire.

Fascism’s civilising mission was graphically portrayed in the opening sequence of the 1935 propaganda film Ti Saluto, Vado in Abissinia, produced by the Fascist Colonial Institute. Against a soundtrack of discordant music there is grisly footage of shackled slaves, a baby crying as its cheeks are scored with tribal marks, a leper, dancing women, an Abyssinian ras (prince) in his exotic regalia, the Emperor Haile Selassie on horseback inspecting modern infantrymen and, to please male cinemagoers, close-ups of naked girls dancing. Darkness and grotesque images give way to light with the first bars of the jaunty popular song of the film’s title, and there follows a sequence of young, cheerful soldiers in tropical kit boarding a troopship on the first stage of their journey to claim this benighted land for civilisation. Newsreels celebrated the triumphs of ‘progress’: one showed a Somali village ‘where the machinery imported by our farmers helps the natives to till the fertile soil’, and in another King Victor Emmanuel inspects hospitals and waterworks in Libya. In the press, Fascist hacks flattered Italy as ‘the mother of civilisation’ and ‘the most intelligent of nations’.

#

Progress required Fascist order. Within a year of Mussolini’s seizure of power in 1922, operations began to secure Libya completely, in particular the south-western desert region of Fezzan. Progress was slow, despite aircraft, armoured cars and tanks, and so in 1927 Italy, like Spain, reached for phosgene and mustard gas. Under Marshal Rodolfo Graziani, Italian forces pressed inland across the Sahara, herded rebels and their families into internment camps and hanged captured insurgents. The fighting dragged on for a further four years, and ended with the capture, trial and public execution in 1931 of the capable and daring partisan leader, Omar el-Mukhtar. Like Abd el-Krim, he became a hero to later generations of North African nationalists: there are streets named after him in Cairo and Gaza.

Somalia too got a stiff dose of Fascist discipline. Indirect rule was abandoned, and the client chiefs who had effectively controlled a third of the colony were brought to heel by a war waged between 1923 and 1927. The bill swelled Somalia’s debts, which were slightly reduced by a programme of investment in irrigation and cash crops, all of which were subsidised by Rome. Italians were compelled to buy Somalian bananas, but their consumption merely staved off insolvency. The flow of immigrants was disappointingly small: in 1940 there were 854 Italian families tilling the Libyan soil and 1,500 settlers in Somalia.

Having tightened Italy’s grip over Libya and Somalia, Mussolini turned to what was, for all patriots, the unfinished business of Abyssinia, where an Italian army had suffered an infamous defeat at Adwa in 1896. Fascism would restore national honour and add a potentially rich colony to the new Roman Empire, which would soon be filled by settlers.

Known as Ethiopia by its Emperor and his subjects, Abyssinia was one of the largest states in Africa, covering 472,000 square miles, and it had been independent for over a thousand years. It was ruled by Haile Selassie, ‘Lion of Judah, Elect of God, King of Kings of Ethiopia’, a benevolent absolutist who traced his descent to Solomon and Sheba. His autocracy had the spiritual support of the Coptic Church, which preached the virtues of submission to the Emperor and the aristocracy. One nobleman, Ras Gugsa Wale, summed up the political philosophy of his caste: ‘It is best for Ethiopia to live according to ancient custom as of old and it would not profit her to follow European civilisation.’

Nevertheless, that civilisation was encroaching on Abyssinia and would continue to do so. In 1917 the railway between French Djibuti and Addis Ababa had been opened; among other goods transported were consignments of modern weaponry for Haile Selassie’s army and embryonic air force (it had four planes in 1935), and European businessmen in search of concessions. The Emperor was a hesitantly progressive ruler who hoped to achieve a balance between tradition and what he called ‘acts of civilisation’.

Frontier disputes provided Mussolini with the pretext for a war, but he had first to overcome the hurdle of outside intervention orchestrated by the League of Nations. Abyssinia was a member of that body which, in theory, existed to prevent wars through arbitration and, again in theory, had the authority to call on members to impose sanctions on aggressors. The League was a paper tiger: it had failed to stop the Japanese seizure of Manchuria in 1931, and economic sanctions against Italy required the active cooperation of the British and French navies. This was not forthcoming, for neither power had the will for a blockade that could escalate into a war against Italy whose army, navy and air force were grossly overestimated by the British and French intelligence services. Moreover, both powers were becoming increasingly uneasy about Hitler’s territorial ambitions and hoped, vainly as it turned out, to enlist the goodwill of Mussolini. An Anglo-French attempt to appease Mussolini by offering him a chunk of Abyssinia (the Hoare-Laval Pact) failed either to deter him or win his favour. Interestingly, this resort to the cynical diplomacy of Africa’s early partition provoked outrage in Britain and France.

Neither nation was prepared to strangle Italy’s seaborne trade to preserve Abyssinian integrity, and so Mussolini’s gamble paid off. The fighting began in October 1935, with 100,000 Italian troops backed by tanks and bombers invading from Eritrea in the north and Somalia in the south. Ranged against them was the small professional Abyssinian army armed with machine-guns and artillery and far larger tribal levies raised by the rases and equipped with all kinds of weapons, from spears and swords to modern rifles.

The course of the war has been admirably charted by Anthony Mockler, who reminds us that, despite the disparity between the equipment of the two armies, the conquest of Abyssinia was never the walkover the Italians had hoped for. In December a column backed by ten tanks was ambushed in the Takazze valley. One, sent on a reconnaissance, was captured by a warrior who stole up behind the vehicle, jumped on it and knocked on the turret. It was opened and he killed the crew with his sword. Surrounded, the Italians attempted to rally around their tanks and were overrun. Another tank crew were slain after they had opened their turret; others were overturned and set alight, and two were captured. Nearly all their crews were killed in the rout that followed and fifty machine-guns captured. The local commander, Marshal Pietro Badoglio, was shaken by this reverse and struck back with, aircraft which attacked the Abyssinians with mustard-gas bombs.

As in Morocco, gas (as well as conventional bombs) compensated for slipshod command and panicky troops, although the Italians excused its use as revenge for the beheading in Daggahur of a captured Italian pilot after he had just bombed and strafed the town. Denials rather than excuses were offered when bombs were dropped on hospitals marked with red crosses.

Intensive aerial bombardment and gas swung the war in Italy’s favour. In May 1936 Addis Ababa was captured and, soon after, Haile Selassie went into exile. He was jeered by Italian delegates when he addressed the League of Nations in Geneva, and was cheered by Londoners when he arrived at Waterloo. He remained in England for the next four years, sometimes in Bath, where his kindness and charm were long remembered. In Rome an image of the Lion of Judah was placed on the war memorial to the dead of the 1896 war; Adwa had been avenged. Mussolini’s bombast rose to the occasion with declarations that Abyssinia had been ‘liberated’ from its age-old backwardness and miseries. Liberty took odd forms, for the Duce decreed that henceforward it was a crime for Italians to cohabit with native women, which he thought an affront to Italian manhood, and he forbade Italians to be employed by Abyssinians.

In Abyssinia Italians assumed the role of master race with a hideous relish. Efforts were made to exterminate the Abyssinian intellectual elite, including all primary school teachers. In February 1937 an attempt to assassinate the Viceroy Graziani prompted an official pogrom in which Abyssinians were randomly murdered in the streets. Blackshirts armed with daggers and shouting, ‘Duce! Duce!’ led the way. The killings spread to the countryside after Graziani ordered the Governor of Harar to ‘Shoot all – I say all – rebels, notables, chiefs’ and anyone ‘thought guilty of bad faith or of being guilty of helping the rebels’. Thousands were slaughtered during the next three months.

The subjugation of Abyssinia proved as difficult as its conquest. Over 200,000 troops were deployed fighting a guerrilla war of pacification. Italy’s new colony was turning into an expensive luxury: between 1936 and 1938 its military expenses totalled 26,500 million lire. In the event of a European war, this huge army would deter an Anglo – French invasion and, as Mussolini hoped, invade the Sudan, Djibuti and perhaps Kenya, while forces based in Libya attacked Egypt. Viceroy Graziani felt certain that Britain was secretly helping Abyssinian resistance and Mussolini agreed, although he wondered whether the Comintern might also have been involved.

By 1938, his own secret service was disseminating anti-British propaganda to Egypt and Palestine via Radio Bari. In April 1939, alarmed by the flow of reinforcements to Italian garrisons in Libya and Abyssinia, the British made secret preparations for undercover operations to foment native uprisings in both colonies. At the same time, parties of young Italians, ostensibly on cycling holidays, spread the Fascist message in Tunisia and Morocco, and Jewish pupils were banned from Italian schools in Tunis, Rabat and Tangier. Africa was already becoming embroiled in Europe’s political conflicts.

#

Outside Germany and Italy, European opinion about the Abyssinian War was sharply divided: anti-Fascists of all kinds were against Mussolini, while right-wingers tended to support him on racial grounds. Sir Oswald Mosley, whose British Union of Fascists was secretly underwritten by Mussolini, dismissed Abyssinia as a ‘black and barbarous conglomeration of tribes with not one Christian principle’. Lord Rothermere, owner of the Daily Mail, urged his readers to back Italy and ‘the cause of the white race’ whose defeat in Abyssinia would set a frightening example to Africans and Asians. Evelyn Waugh, who was commissioned by Rothermere to cover the war, confided to a friend his hopes that the Abyssinians would be ‘gassed to buggery’.

Such reactions, and the moral insouciance of Britain and France, shocked educated Africans in West Africa. The Abyssinian episode had tarnished the notion of benevolent imperialism cherished in both nations, and seemed to condone views of Africans as a primitive people, beyond the pale of humanity as well as civilisation. In the words of William Du Bois, an American black academic and champion of black rights, the Abyssinian War had shattered the black man’s ‘faith in white justice’. Harlem blacks had volunteered to fight, but had been refused visas by the American government. Du Bois believed that their instincts had been right, for in the future, ‘The only path to freedom and equality is force, and force to the uttermost.’