In the 1860s, Russian expeditionary forces entered Uzbekistan and captured the key trading cities of Tashkent and Samarkand. In the 1870s the Russians turned their attention to Khiva, capital of the Turkomans, lying to the south of the Aral Sea on the border between Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. By the end of these campaigns, the empire had been expanded by 210,000 sq km (80,000 sq miles) and the Russian frontier had advanced 500km (300 miles) southwards. The Turkomans had not been wholly beaten, however, and merely retreated into the wilderness. It was then that the Russians found themselves in trouble.

Mikhail Dmitriyevich Skobelev (29 September 1843 – 7 July 1882) was a Russian general famous for his conquest of Central Asia and heroism during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878. Dressed in white uniform and mounted on a white horse, and always in the thickest of the fray, he was known and adored by his soldiers as the “White General” (and by the Turks as the “White Pasha”). During a campaign in Khiva, his Turkmen opponents called him goz zanli or “Bloody Eyes”. British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery wrote that Skobelev was the world’s “ablest single commander” between 1870 and 1914 and called him a “skilful and inspiring” leader.

In 1839, Arthur Connolly, an intelligence officer with the East India Company, described the competition between Great Britain and Russia for control of Central Asia as “the grand game,” and the phrase became widely popular as “the great game” after writer Rudyard Kipling used it in Kim, a novel published in 1901. The rivalry dated from 1813, when (after a lengthy conflict) the Russians forced Persia to accept their control of much territory in the Caucasus Mountains region, including the area covered by modern Azerbaijan, Dagestan, and eastern Georgia. British politicians feared that the tsars’ expansionist ambitions would carry them further south and threaten the commercially and strategically important imperial possessions in India so the government attempted to make Afghanistan a buffer state that would prevent Russian armies from attacking through the Bolan and Khyber Passes in the Himalayas. In the early 20th century, the struggle extended to Persia and Tibet, but by then both powers considered Germany a growing threat so on 31 August 1907, in St. Petersburg, they signed an entente that circumscribed their areas of influence in Persia and ended Russian contacts with the Afghans.

The Great Game

The name attributed to the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century competition for colonial territory in Central Eurasia. Tsarist Russia and Great Britain were the primary actors in this ongoing diplomatic, political, and military rivalry. The term Great Game was first widely popularized in Rudyard Kipling’s novel Kim, first published in 1901. British Captain Arthur Connolly, however, was believed to have coined the phrase in his Narrative of an Overland Journey to the North of India in 1835. Since then, it has been the subject of countless historical studies. It should be noted that Russian speakers did not refer to this period of colonial rivalry as the Great Game, but certainly acknowledged this important period of its own historical record. Among Russian speakers, the Great Game competition is referred to as the “Tournament of Shadows.”

The Great Game is generally accepted to date from the early nineteenth century until the 1907 Anglo-Russian Convention, although some scholars date its conclusion to later in the twentieth century. The Anglo-Russian Convention is also referred to as the Convention of Mutual Cordiality or the Anglo-Russian Agreement and was signed on August 31, 1907. The convention gave formal unity to the Triple Entente powers, consisting of France, Great Britain, and Russia, who would soon engage in future diplomatic and military struggles against the earlier-formed Triple Alliance, consisting of Austria-Hungary, Germany, and Italy. The agreement also confirmed existing colonial borders. Great Britain and Russia agreed not to invade Afghanistan, Persia, or Tibet, but were allowed certain areas of economic or political influence within those regions.

In contemporary history, popular media often speak of many new “Great Games.” This term has become customary for discussing any sort of diplomatic or stateorganized conflicts or competitions in the Central Eurasian region. These new Great Games are often mentioned in disputes over oil or natural resources, diplomatic influence or alliances, economic competition, the opening or closing of military bases, the outcomes and maneuvering for political elections and offices, or any number of other contemporary issues in Central Eurasia. Russia, the United States, China, Turkey, the European Union countries, East Asian states, and various Islamic-influenced countries are often portrayed as the major competitors of these contemporary Great Games.

The historical roots of the Great Game are planted in a period of sustained mutual fear and mistrust on the part of Britain and Russia throughout most of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Both British and Russian leaders feared that the other side would encroach on their territorial holdings and would establish preeminent colonial control in the Central Eurasian region. It was widely believed that this would escalate into a war between the two powers at some point, but this never happened. Russia and Britain, however, did engage in a considerable amount of military ventures against various peoples of Central Eurasia. The conflicts ranged from diplomatic squabbles to shows of military force to full-blown wars.

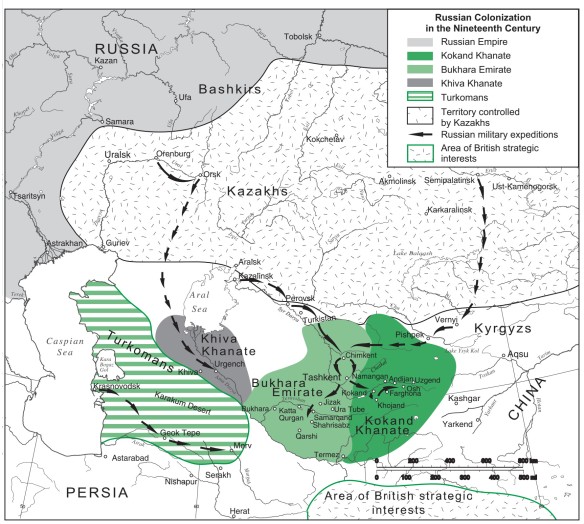

During the early nineteenth century, Russia became increasingly interested in solidifying its southern borders. The Russians gained allegiance from various Kazakh hordes during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. They still faced opposition from many Kazakhs, however, including Kenesary Kasimov, who led a sustained rebellion of Kazakhs against Russia from 1837-1846. Much of the early nineteenth-century Russian attention in Central Eurasia was directed toward quelling Kazakh resistance and ensuring secure southern borders for the empire. By 1847, the Russians finally succeeded in bringing the Greater, Middle, and Lesser Kazakh hordes under Russian control. In response to its defeat in the Crimean War (1854-1856), Russia turned its military attention away from the Ottoman Empire and the Caucasus and instead toward eastward and southward expansion in Central Eurasia. The terms of the 1856 Treaty of Paris effectively forced Russia to relinquish its interests in Southwest Asia, spurring a new round of imperial interest in Central Eurasia. Russian advances in Central Eurasia were both offensive and defensive moves, as they conquered the only areas left to them and hoped to position themselves against future British encroachment in the region.

The British government became increasingly alarmed over the southward movement of the Russian armies throughout the nineteenth century. Russian conquest of the Kazakh steppe was followed by mid-century attacks on the Central Eurasian oasis empires of Khokand, Khiva, and Bukhara. The Russians began a new wave of conquest in 1864 by conquering the cities of Chimkent and Aulie Ata. Khokand was defeated in 1865 and with the unexpected Russian attack and conquest of Tashkent in 1865 by General Mikhail Cherniaev, tsarist Russia was in a position to launch a string of attacks in the latter 1860s and throughout the 1870s that struck fear in the hearts of the British. The Russians then conquered the Bukhara state in 1868 and the Khiva khanate in 1873. Both Bukhara and Khiva were granted the status of Russian protectorates in 1873. The Turkmen of Central Eurasia put up particularly strong resistance to Russian conquest during a long period of fighting between 1869 and 1885. As with most of the other areas, the Russians considered controlling the Turkmen and their territory as essential for resisting possible British incursions. The Russian victory over the Turkmen at the Battle of Göktepe in 1881 was crucial. The final Russian territorial acquisition in Central Eurasia was at the oasis of Merv in 1884. The Russians considered this conquest especially important because of its proximity to Afghanistan. As the Russian southward advance continued, British colonial officials became increasingly concerned that Russia may attempt to continue southward and attempt to take the jewel in the British colonial crown, India. The British had maintained economic and political influence over South Asia since the early seventeenth century, initially through the British East India Company’s economic ventures. Although India was not a formal British colony until 1858, with the suppression of the Sepoy rebellion, Britain enjoyed strong commercial and political influence over the area throughout the nineteenth century. Russians feared British interest in areas they considered to be in their own colonial backyard-especially Afghanistan, Persia, and Tibet.

The Great Game included two major wars between the British and the leaders of Afghanistan, with disastrous results for the British. The British hoped that Afghanistan could serve as a buffer state in defense of Russian advances toward India. The First Anglo-Afghan war lasted from 1839 until 1842. In this war, the British attempted to replace current Afghan leader Dost Muhammad Khan with a leader more amenable to British control, Shuja Shah. The Second AngloAfghan War was fought from 1878-1880, again over issues of British political and diplomatic influence in Afghanistan. In both conflicts the British faced harsh opposition in Afghanistan; however, after the second conflict, they were able to establish considerable control over Afghan politics by placing Abdur Rahman Khan in power. Abdur Rahman Khan ruled Afghanistan until 1901, largely in service of British interests in the region. He was able to quell opposition to the idea of a unified Afghanistan during this period. Perhaps his biggest test of political leadership came in 1885 in Panjdeh, in northern Afghanistan. Panjdeh was an oasis area, which the Russians wished to claim. After much diplomatic wrangling, the dispute was resolved and the Russians and Afghanis agreed to a border at the Amu Darya River, ceding Panjdeh to the Russian Empire. During the early 1890s, the Russians attempted to continue a southward push through the Pamir Mountains to India’s frontier of Kashmir. At this point mutual fears had reached a crisis situation, but they were temporarily resolved through the work of the Pamir Boundary Commission in 1895. This agreement paved the way for the formal acknowledgment of Russian and British colonial possessions in Central Eurasia through the 1907 Anglo-Russian Convention. The Pamir Boundary Commission of 1895 set the definitive boundaries for the Russian Empire in Central Eurasia.

The Russians faced two major setbacks in the early twentieth century, the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, and the Revolution of 1905. As a result of these two reversals and amidst the backdrop of an emerging alliance system among the major European powers, the Russians became interested in resolving their disputes with Great Britain. In 1907, both sides agreed to a cessation of the Great Game competition by agreeing to the Anglo-Russian Convention on August 31. Under the terms of this agreement, both sides settled their disputes over territories in Central Eurasia-including Afghanistan, Persia, and Tibet-and forged a military and diplomatic alliance that they would carry into World War I.